What the heck kind of a name is Gutbuster Peak? No map I had ever seen called it that. Must be one of those informal local names people drop on mountains all over the world. It sounded intriguing enough, though – so much so that I figured I had better go and try it. The USGS topo map had given it a spot elevation of 6,730 feet – a popular climbing website had given it the name.

The forecast predicted a high of 93 degrees for Tucson, which translated to about 80 for Gutbuster’s summit. That was more than doable. I set out at daybreak with a full tank of gas. Seventy miles of pavement took me to my turnoff, where this sign greeted me.

Another sign nearby stated that I was entering Arizona State Trust Land, and “No Trespassing, Permit Required”. Sure, uh-huh, you betcha. Three more miles of driving, this time on a bone-jarring, stone-covered dirt road, took me into the Coronado National Forest, where I finally parked in a shady glen. En route, I had my first good view of the peak. There sure were a lot of cliffs on that thing!

It was 8:00 am, nice and cool, and it just felt like it was going to be a good day. French Joe Canyon was a nice place – it was heavily wooded, and a small trickle of water flowed through it. I soon discovered why. About half a mile upstream from where I had parked, I arrived at French Joe spring. Perhaps someone named French Joe had lived there long ago, but now all that was there was an old concrete trough which had been fed by a pipe from the spring.

After another quarter-mile of walking upstream, I found what I was looking for – a gentle drainage coming in from the high country on the north side of Gutbuster. A series of rocky shelves greeted me as I started uphill, and, once over these, the honeymoon was over. There I stood, staring into a vast sea of brush. This range, the Whetstone Mountains, is famous for its thick vegetation. If you’re looking for a world-class bushwhack, this is it. I knew this coming in, but it was no less daunting to be standing there and preparing to enter the belly of the beast.

I mean, look at the picture above – it looks harmless enough, right? Just a nice green mountainside, right? Well, hoooooold on there, Baba Louey!! Looks can be deceiving, and in this case they surely are. You are staring at more than 1,500 vertical feet of hellish fun. Those of you who have climbed up through this type of country can relate to what I am about to describe, but in case you haven’t, I will try to bring it to life for you.

I mean, look at the picture above – it looks harmless enough, right? Just a nice green mountainside, right? Well, hoooooold on there, Baba Louey!! Looks can be deceiving, and in this case they surely are. You are staring at more than 1,500 vertical feet of hellish fun. Those of you who have climbed up through this type of country can relate to what I am about to describe, but in case you haven’t, I will try to bring it to life for you.

You take the first few steps and quickly realize that you must try to forcibly push your way through what is, essentially, a solid wall of vegetation. Some of these plants are small, only a foot high, but others are well over your head. You try to push them aside so you can continue to move forward, but they push back. Many of these plants are covered with spines, very sharp spines, which can poke through your clothing and draw blood. Some, like catclaw, just want to hang on to you and not let go. In any case, go you must, so you push ahead. If you’re lucky, you can find lanes where the brush is a little less nasty, a little more open, and you can make better progress. More often than not, though, you find yourself stopping and planning your next move, trying to figure out the best way to proceed. Your pack gets caught on branches, your hat gets torn off your head, your sunglasses get knocked off. There can be other surprises too – cactus can lie in wait, unseen because the vegetation is so thick, so that you walk right into them. At ground level, shin daggers can have their way with you.

For those among you who have not had the pleasure, allow me to introduce you to shin daggers. They have stiff stems with needle-sharp points which can poke through just about anything, including leather gloves. They are just tall enough to painfully jab your ankles and calves, and, having messed with them even once, you will give them a wide berth. That becomes harder when they cover a wide area and your path leads right through them. And all of this bushwhacking is made even more difficult because you are fighting uphill against gravity.

For those among you who have not had the pleasure, allow me to introduce you to shin daggers. They have stiff stems with needle-sharp points which can poke through just about anything, including leather gloves. They are just tall enough to painfully jab your ankles and calves, and, having messed with them even once, you will give them a wide berth. That becomes harder when they cover a wide area and your path leads right through them. And all of this bushwhacking is made even more difficult because you are fighting uphill against gravity.

In any case, I forged ahead, gaining ground much too slowly for my liking. My next concern was making my way through the cliff bands that guarded the upper part of the mountain. Actually, this went pretty well, considering the double jeopardy of bushwhacking through cliffs. I found a pretty good way through the highest cliff band, with just a bit of Class 3 scrambling.

Once through the cliff band, another few hundred yards of especially nasty brush and trees brought me to the summit ridge at about 6,580 feet elevation. Truth be told, that last hour of climbing was, at times, in such poor visibility that I left a trail of fluorescent pink flagging tape tied to branches to help me more easily retrace my path through the brush and cliffs. My objective was now in plain view, not quite half a mile to the southeast.

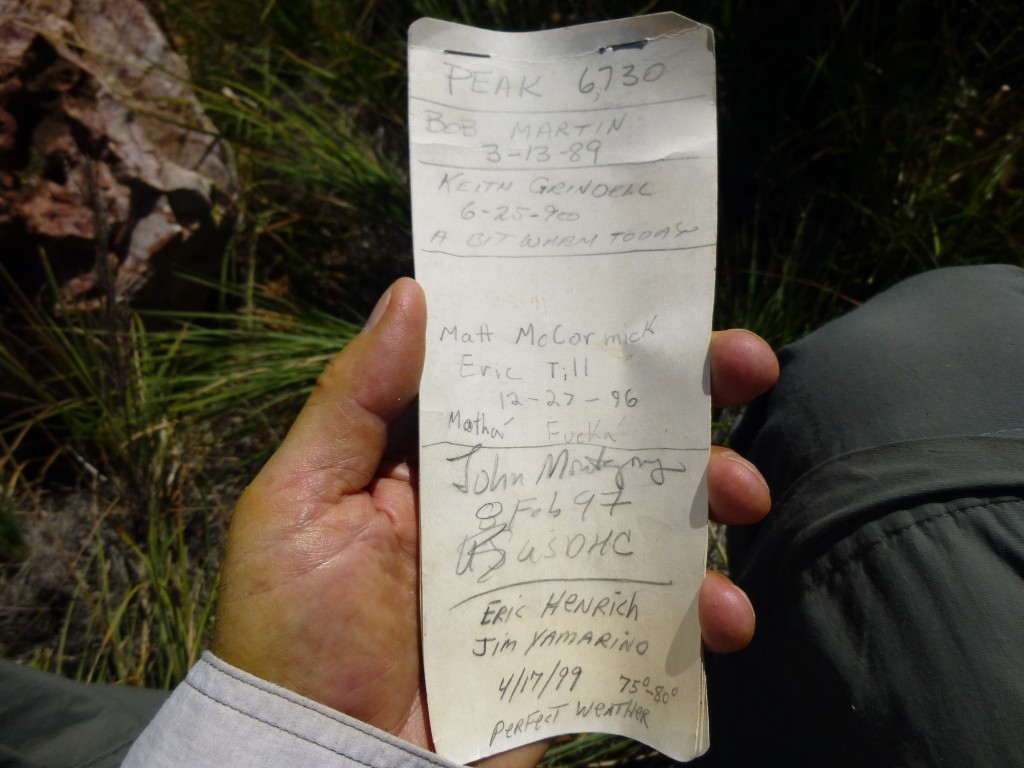

All I had to do now was wade through waist-high brush, drop into a small saddle, then climb the last 200 vertical feet to the summit. It went without incident, and I stood on the summit at 10:45 am. The climb had taken a full 2 1/2 hours from where I had parked. In short order, I found a cairn (a pile of rocks left by climbers) and inside it was a register (in this case, a glass jar which contained a pencil and paper). Registers such as these act as a historical record, tracking those who reach the summit. Of course, you would need to know that the register was there in the first place, but any climber would, and maybe some others as well, such as hunters or law enforcement. Here is a photo of the first page of the register.

This register was placed by the late Bob Martin way back in 1989, and nine additional parties had signed in since then, including me – a total of ten ascents in twenty-three years. I spent some 15 or 20 minutes on the summit, had a bite to eat and enjoyed the scenery.

But it was time to leave – I stashed the register back in the cairn, readied my pack and set out downslope. Before long, I soon regained the area where my flagging started, and braced myself for the thrash that was inevitable. It went surprisingly well, and an hour later I was back down in French Joe Canyon, glad the hard slugging was over, because I could feel my leg muscles getting ready to cramp up. Foolishly, I had only taken three quarts to drink for the whole day, not enough – it should have been five. I made it back to my truck and drank two more – that helped.

While driving out, there were places where puddles were drying in the sun and I noticed something curious. Dozens of butterflies were sitting on the damp earth – I’m guessing they were somehow drinking up moisture. There were as many as four different species together in each spot.

It had been a good day – a total of about 2,000 vertical feet and 4.7 miles on foot, with enough high-quality bushwhacking during the almost-five-hour outing to satisfy even the most masochistic among you.

It had been a good day – a total of about 2,000 vertical feet and 4.7 miles on foot, with enough high-quality bushwhacking during the almost-five-hour outing to satisfy even the most masochistic among you.

Please visit us at our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690