Back in the winter of 2004, Andy Martin and I decided to head down to Mexico to climb a big volcano in northern Sonora. Both of us had thought of doing it for some time, and that time had come. Most people call it Cerro Pinacate, although it is also known as Cerro del Pinacate, as well as Volcán Santa Clara. At 3,904 feet elevation, it towered over everything else for a long way around. The explorer Melchior Díaz was probably the first white man to visit the area, way back in 1540. Father Eusebio Kino visited the area and climbed the peak around 1700, and was the one who named it Santa Clara.

There are some things you need to know about this area. The mountain sits in the midst of a group of peaks and cinder cones called the Sierra Pinacate, or Cuk Do’ag in the Tohono O’odham language. The peak lies near the southeast edge of the huge sand dune field of the Gran Desierto del Altar (these dunes are the largest in all of the Americas).

The most recent volcanic activity happened about 11,000 years ago. The peaks and dunes are all within the El Pinacate y Gran Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve, which is administered by the Mexican federal and state governments. Within its 600 square miles sit over 400 cinder cones and nine huge volcanic craters. Much of the terrain is positively lunar in nature, which explains why, from 1965 to 1970, NASA sent astronauts there to train for future missions to the moon.

Well, enough of that for now. Here it was, January 18th, and we were wheeling our way south, Mexican auto insurance in hand. As we drove south from the border town of Sonoita on the highway to Puerto Peñasco (a playground for beach-starved Arizonans), we kept a sharp eye out for the road we thought would lead to the mountain. The details are somewhat sketchy now, but I remember driving around for a while, looking for an elusive dirt road that would take us west to our goal. Seems to me we might have taken matters into our own hands once when a fence got in our way, but then continued driving until we stopped at a place Andy had pre-ordained. Why not climb something on the way in?

We made short work of Peak 1339, the high point of the Sierra Suvik. Didn’t find any sign of a previous visit, so we built a cairn and left a register on the summit. Once done, we continued driving until we arrived at a simple campground at Cono Rojo. This was done without seeing any entrance station or paying any fees. We had the place to ourselves, and settled in. There was still daylight left, so I did a quick climb of Cono Rojo (1,756′ elevation) while Andy hung out at our campsite.

The next morning dawned clear and chilly, probably not much above freezing. We got our stuff together and headed on out. A trail actually leaves from the campground, and follows an old road which, we had heard, actually goes much of the way to the summit. After a short while, though, we didn’t much care for the direction the road was heading, so we took off cross-country through a dramatic lava field. The lava was twisted into all kinds of crazy shapes, and it took us a while to work our way through it.

We couldn’t see our summit yet, as another lower mountain named Carnegie Peak was in the way. Once through the lava field, we climbed up the slopes of Carnegie and gained quite a bit of elevation. At long last, we had our first real views of Cerro Pinacate. Also, in the distance, we could see a huge crater down on the desert floor. It did look like something on the moon.

There were places, especially higher up, where we had to climb up slopes that were covered in deep cinders. This was tiring because there was constant sliding back down even while we made upward progress. Eventually, though, we went up the final slopes and arrived on the summit. Finally – it had been quite a grind! But it had all been worth it – the views were spectacular.

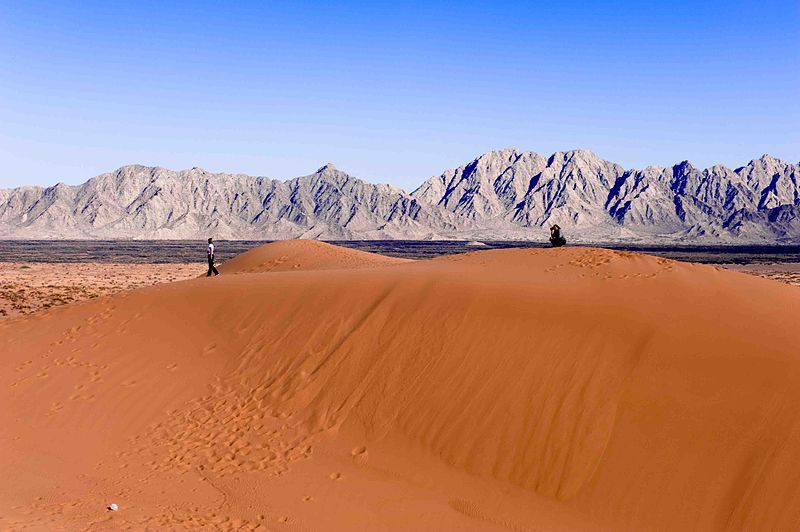

Less than twenty miles away was the Sea of Cortez, also known as the Gulf of California. In the next photo, you can see the sand dunes in the Gran Desierto del Altar, out beyond the mountain slopes, and a bit beyond the dunes is the Pacific Ocean.

Although I have never visited the dunes, some of my friends have done so, and report that it is an amazing place. There are mountain ranges that lie entirely within the dunes – some of them are almost buried. This next photo shows a bit of that. It is a long telephoto shot.

On the summit was a metal ammo box that contained the register. We signed in and ate our lunch.

The views were great, and we soaked it all up, taking lots of photos. Eventually, though, as on all summits, it was time to leave. It’s always hard to know how long to stay on top, because you could run into anything on the way down, including unforeseen problems. Getting down is usually quicker than climbing up, but not necessarily.

We retraced our steps and in a few more hours were back at the campground. I believe our round-trip may have taken as much as seven hours. It was still plenty early, so we packed up the truck and headed out. One thing that had been on our minds was that there had to be a better way in to the peak, so we drove north on some other roads to see where they would take us. After some miles, the roads started to improve, and we began to see other vehicles. Tourists, not climbers, were in those vehicles. Finally, we came to a turnoff and a parking spot for one of the craters. A short walk took us to the lip, where we had these terrific views into the crater itself. We were at Crater El Elegante. It was perfectly circular, about 460 feet deep and 4,600 feet in diameter.

This crater is of a type known as a “maar” crater. What the name means is that hot magma hit an underground pocket of water and caused a huge explosion. Wow, that really shows the power of steam, doesn’t it? These craters usually have flat bottoms, and commonly fill with water. I guess there wasn’t enough water here to fill it up – the evaporation rate would be so great that water wouldn’t sit for long. Summer temperatures here are extreme, partly aggravated by the dark-colored lava rock, and can reach 120 degrees in the shade.

We saw people walking around the edge of the crater. Perhaps there was even a trail to the bottom, but I don’t know if the public was allowed to go there. We stayed for a short while, then continued to drive north past grotesque lava shapes. This place is worth visiting just to see the lava alone. As we neared Mexican Highway 2, we finally passed a small structure which seemed to be an entry point into the biosphere reserve. Hmmm, maybe this was the main entrance into the area. In any case, the whole place is spectacular and I would highly recommend it to anyone, day-trippers and climbers alike.

Please visit our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690