In the autumn of 1995, Brian and I were talking about climbing (what else!) and decided that we needed to go climb something high and cold. As the months passed, the Andes seemed like a good bet. Of course, the range passes through many countries, so we had to narrow it down, and Bolivia seemed like a good choice. Plenty of nice peaks there, in any of several ranges, and also the free-standing stuff out on the Altiplano.

In the meantime, Dottie and I had settled in to a new home. She was becoming more accustomed to the idea of my going away on such a trip, but I know she still had misgivings. Can’t say I blamed her. Brian and I hammered out all the details ad infinitum as the winter and spring rolled on by. By the time the summer had arrived, it was time to go. During the last few days at home, all our close friends had called to wish me luck. Dottie drove me to the airport early on Thursday, June 20th and we said a quick good-bye.

This was back in the days when you didn’t have to pay extra to check luggage, so my 70-pound duffle bag sailed right on through. No big deal with my 30-pound day pack either. My two-hour flight to Dallas took off on time. Once I landed, I had a quick turn-around in the airport to get to my next flight. As luck would have it, though, I sat and cooled my heels for quite a while waiting for the plane to arrive at the gate. Dallas was a sauna, 101 degrees with its usual outrageous humidity. I was glad to finally get airborne. Another 2 1/2 hours brought me to Miami, where Brian was waiting.

It was good to see him again – it had been seven years since our last climb together, on Canada’s Mt. Robson. “Holy crap, he’s gone bald!” I thought when I first saw him, but then realized he’d shaved his head. It suited him then, as it still does today. It was a great reunion – we easily killed the seven-hour layover in the airport. After a good supper, we just sat around and talked.

While waiting for our flight, we met three Japanese climbers who were on their way to Illimani and Huascarán. It was pretty cool talking with them. At long last, we took off in our 757, a nice plane at the time. We had the bulkhead seats, which was mighty fine – lots of legroom. They fed us a good supper at 2:00 a.m. with lots of free wine. That’s a nice feature of these South American flights, the wine – if they didn’t give it to you, there’d be a riot for sure. We settled in for the overnight flight, and then things started to get interesting. A guy passed out cold and did a face-plant in the middle of the aisle. After that, an elderly woman kept going up to the front of the plane to the exit door. The stewardesses tried repeatedly to get her to stay in her seat, to no avail. In frustration, one of them came up to us and asked us if we spoke Spanish. I volunteered my services and started talking to her. Turns out the poor thing must have been suffering from dementia – she was convinced she was on a train which was going to the moon, and insisted on getting off. They finally got her belted in and things calmed down.

I was curious to see what the cabin pressure would be on the flight – they set it at a comfortable 6,500′. The reason I was wondering – the El Alto airport at La Paz, Bolivia sits at 13,200 feet above sea level, arguably the highest commercial airport on the planet. There is a higher paved runway in Tibet but it doesn’t serve a major city like La Paz. As we were on our final approach, they raised the cabin pressure to 14,000′, then let it drop a bit to be equal to that of El Alto. It’s a well-known fact that passengers deplaning at El Alto can experience symptoms of altitude sickness. Supplemental oxygen is in plain sight inside the terminal building. When we disembarked, we were both a bit concerned that we might have an adverse reaction to the sudden altitude, but our fears were unjustified.

The terminal was a mean, spare place. We paid a guy two dollars to haul our huge bags around the airport, then caught a cab for six bucks more which took us all the way to a hotel in the city center. In the four years since my Bolivia guidebook had been published, a double room with private bath at the Hostal República had gone from $13.50 to $22.00 US. There were plenty of cheaper places, but this one offered reasonable comfort for the price.

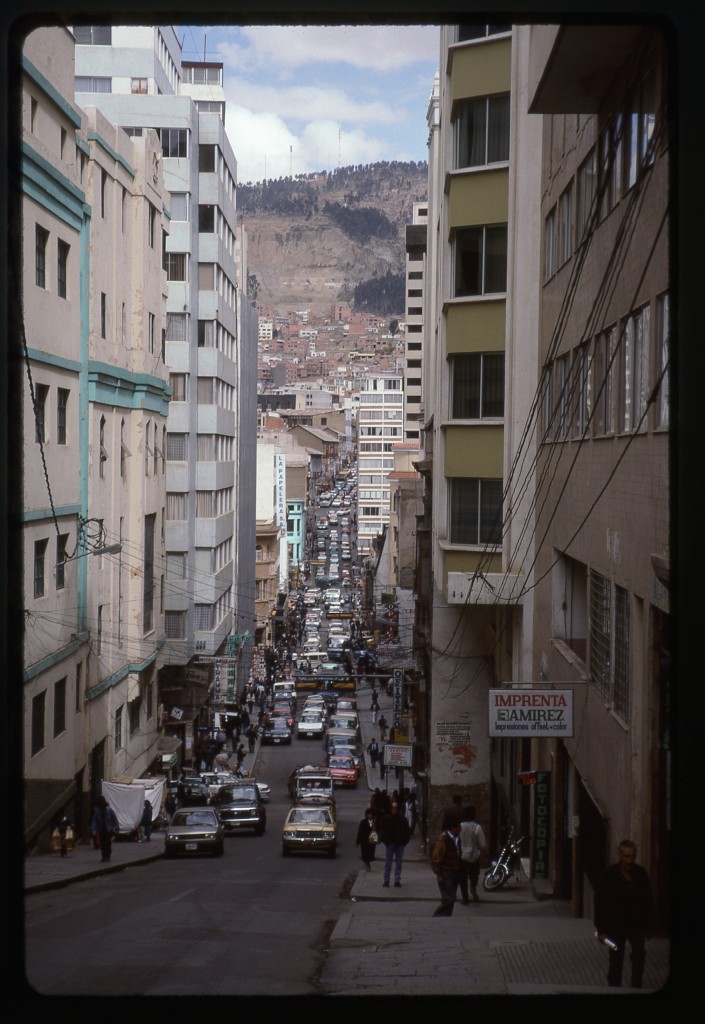

La Paz is in quite a unique setting. From the airport, which sits on the flat Altiplano above the city, the road drops down dramatically into a huge bowl. The city lines the bowl, crawling up its sides. In many cities around the world, the rich folks live up on the heights and the po’ folks live down below. The opposite is true in La Paz, mainly because elevations here are so extreme. The wealthy want to live in the lowest reaches of the city, down near 11,000′ or so, because the climate there is more moderate and there’s more oxygen to breathe.

Once at the hotel, we left our gear in a pile near the front entrance while we checked in. The only mishap of the entire trip happened at that time. While our backs were turned, somebody made off with Brian’s summit pack. The biggest loss was his water filter inside the pack – the rest. clothing and the like, we had extra so were okay there. The hotel staff were visibly upset over the theft. They were incredibly helpful, and went out of their way to do anything possible to look after our needs during our stay. The hotel used to be the home of a former Bolivian president – I can’t tell you which one, as there are a lot from which to choose – they seem to have a new one every year or so!

Here was our plan in the simplest terms – we would hang out in La Paz a few days and acclimate, then find transportation across the Altiplano to Nevado Sajama, Bolivia’s highest peak at an elevation of 21,491 feet. From the reading we had done, it appeared that it was an arduous overland journey to Sajama on poor dirt roads. In our hotel, we noticed an office for some travel company. The young woman who worked there made a few phone calls on our behalf and quickly learned that a bus ran from La Paz to Arica, on the Pacific coast of Chile. And to top it all off, a bus was leaving the next morning. She said she could sell us two tickets, and recommended we act on it quickly as the bus only went two or three times a week and always sold out.

Yikes, that was awfully soon, not giving us much time to acclimate. Our hotel sat at an elevation of 11,750′ and a few nights spent there would have been great for us to get used to the high elevation. Mountaineering wisdom says you should gain elevation slowly over a period of time in order to acclimate properly and not suffer any symptoms of acute mountain sickness. Leaving the next morning seemed to be pushing things a bit too quickly, but we decided to seize the moment and bought two tickets for $24.00 US each. That fare covered the trip all the way to Arica. It didn’t matter that we only wanted to go half that distance – we took up two seats, which could have been sold to others who were going the entire distance.

With errands to run in the short time we had left in the city, we set out on foot from our hotel. One other thing that we no longer had due to the theft of Brian’s pack was his street shoes. He had been wearing his high-altitude mountaineering boots since leaving Toronto. Thankfully he still had those, as our trip would have been over before it had started if they had been lost. I felt badly for him as he walked the streets of La Paz in those heavy boots, as they were very uncomfortable, to say the least, but he said he’d be fine. We bought lunch at a vegetarian restaurant, found a map of the Sajama area, and exchanged money. The rate was 5.06 Bolivianos to the US dollar.

There was one other thing we wanted to do. Research had shown us that coca-leaf tea had been used for centuries to help people better deal with high altitude. The tea had none of the narcotic effects of the cocaine produced from the same plant. Even so, we felt a bit uneasy looking for the tea. It turned out to be incredibly easy to find – you could buy it loose or in tea bags.We bought a box of tea bags with the brand-name of Windsor. It was sold everywhere and was dirt-cheap. We had some with lunch, and kept drinking it during the rest of the day. It was pretty bland, but, we hoped, was working its magic. As the day progressed, we felt really good and showed no ill-effects of the altitude – that helped us feel that we had made the right decision to leave La Paz so soon.

In the afternoon, we rested for a while. The hotel owners surprised us by bringing us a big jug of kerosene (we had been asking earlier where we could get fuel for our mountaineering stove). They wouldn’t take any money for it, so we gratefully filled all of our fuel bottles. Later, we went out to an office of Entel, where I called Dottie back in the States. Then another easy-to-digest meal at the same vegetarian restaurant. Once back at the hotel, we picked up our bus tickets, then sorted out all of our gear into three piles. One pile was stuff we didn’t need for the climb – it would stay at the hotel in La Paz. A bigger pile was stuff that we would leave as reserves in the village of Tomarapi on the north side of the mountain. The third and largest pile would be everything we needed on the mountain itself. Erring on the side of caution, we were bringing eight 1 1/2-liter bottles of water with us, which made our gear disgustingly heavy. We settled our hotel bill, then turned in by 10:00 pm and slept well.

At 5:00 am the next morning, the hotel gave us a wake-up call. At the front door, our taxi was waiting. For the princely sum of $1.40, he took us to the terminal where we would catch our bus.

After coca tea with two German lads, we boarded our bus and rolled out of the city at 7:05 am. It was hard to believe that we had only been in the country for 24 hours.

Stay tuned for the next part of our adventure entitled “The Altiplano”,

Please visit our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690