As our bus drove up the steep road out of La Paz, we watched the slumbering city drop away below us. At the top of the incline lies the flat Altiplano and the city of El Alto, one of the highest major cities in the world. The 2010 census showed a population of 1.2 million, and the city sits at an elevation of 13,600 feet. As you can imagine, the city’s climate is not one that would attract a lot of tourists – the maximum summer temperature reached here is 63 degrees F.

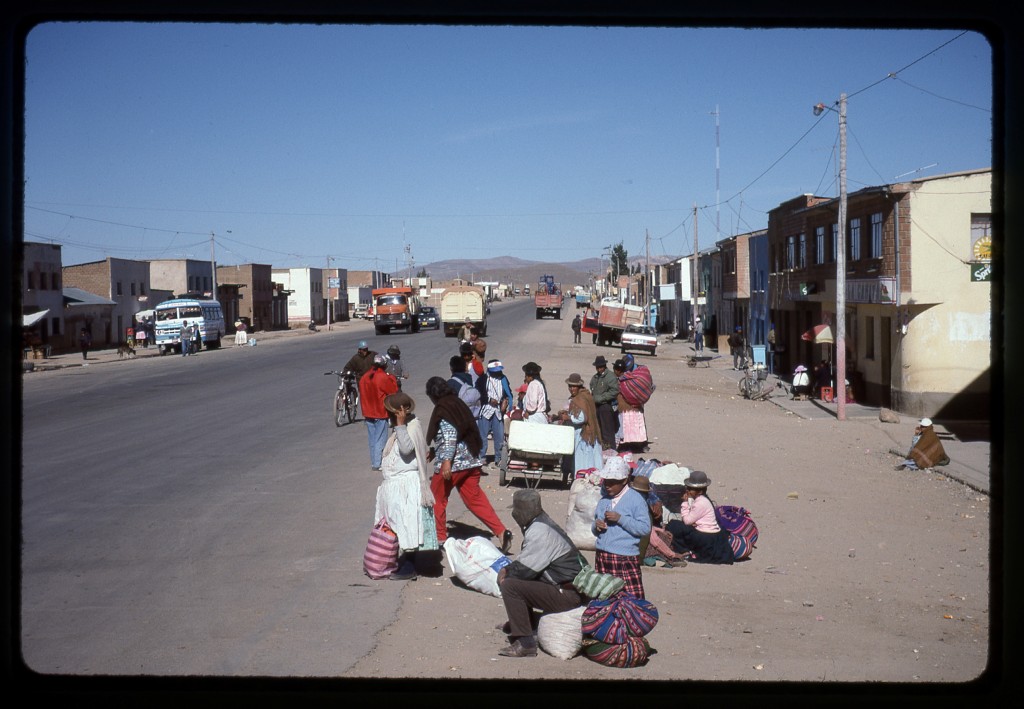

Once through the sprawl of El Alto, the bus continued south through dry, rolling country. We made a stop at Patacamaya where they fed us a continental breakfast. Here’s something worth knowing about Bolivia – it has the highest percentage of Indian inhabitants of any South American country. The two main groups are Aymara and Quechua. And the very name of the town we were now in has an interesting history. In the 1920s, a war occurred between these two ethnic groups. The name Patacamaya is a combination of two words, pataca meaning “100”, and amaya meaning “dead”, a reference to the casualties of the war. Although this town is small, it sits at an important crossroads.

We had been traveling southeast from La Paz for 100 km on Highway 1, the route which continued on to Oruro and Cochabamba. But leaving from Patacamaya was another road which was the one our bus would travel. It was called the “Arica – La Paz Highway” and was one of the most important international routes in the country. We had read that this highway was a rugged road which was slow and difficult to travel, so you can imagine our surprise, even shock, to discover that it was paved as it headed west out of town.

Others on our bus told us that the paving had only been completed a few months earlier. It was paved all the way to the Chilean border, a distance of 193 km, and then all the way to the Chilean seaport of Arica, an additional 232 km. It took 50 years of political squabbling to overcome the obstacles to Bolivia’s paving of their part of the road, but it was done! We sat back and enjoyed the ride. I remember seeing llamas in their natural setting for the first time in my life as we motored on. Before long, though, we had our first glimpse of something on the far horizon that we had been waiting to see – something very white poking up into the sky. It had to be Nevado Sajama, the mountain we had come all this way to climb.

The old road had traveled along the north side of the mountain, through the village of Tomarapi, and then down the west side to the hamlet of Lagunas near the border with Chile. We would have the bus drop us at Tomarapi, then plan our climb from there. As the kilometers rolled by and we approached Sajama, it was hard to not be excited. The mountain was huge and dominated everything for many miles.

We took plenty of pictures through the bus windows as it came nearer, but at some point I realized that something was very wrong. The highway, instead of going to Tomarapi, was heading along the east side of the mountain. It then curved around and passed to the south of the peak and, before you knew it, we were approaching the village of Lagunas. When they paved the highway, they must have decided to re-route it. Our only option now was to disembark at Lagunas and take our chances from there.

I hurried to the front of the bus and asked the driver if we could get off at the village. He must have thought we were nuts, wanting to get off at such a God-forsaken place, but quickly agreed and pulled over on the side of the highway. Brian and I got out and the driver unloaded all our gear and left it on the side of the road. What a view! Sajama was very close, its summit only nine km to the north of us.

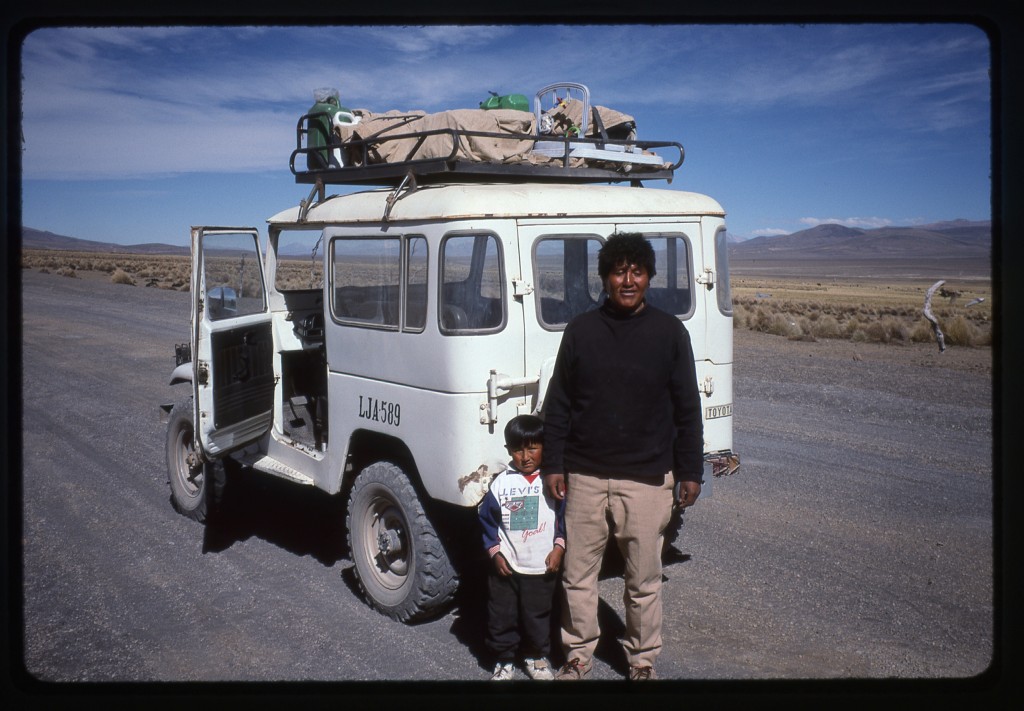

Before coming to Bolivia, we had read something about a foreigner named Peter Brunhart who lived near the mountain. I can’t remember if he was a climber or not, just that we had the impression he might be a good person to contact for help with climbing the mountain. Brian and I decided that he would sit with our gear on the side of the road while I walked into the village to learn more. A short walk on the dusty road took me to the collection of simple buildings that was Lagunas. I started asking people if they knew the whereabouts of this Brunhart fellow, and they told me he lived in another village called Sajama, about 11 km farther north. I started to ask about the possibility of hiring a vehicle to drive us to Sajama village when I saw a jeep approaching. I flagged it down. Turns out it was Eddy, the local school teacher – he and his family were just leaving for a vacation in La Paz. He agreed to drive us, so he left his family there, I hopped in and we went back out to the highway. Brian was sitting there admiring the world-class view as we pulled up.

We loaded all our gear into the jeep and headed north on the excellent dirt road. The teacher then told us about a man who lived about half-way to Sajama village who had pack animals and could be hired to haul our gear up to the base camp for the climb of Sajama. We had to stop at a couple of different homes along the way and ask directions, but soon drove to a home where we found our man. He agreed to help us out, and suggested we wait for him at his place. Eddy drove us there and dropped off us and our gear. He asked for $6.00 US each, which we gladly paid – he then headed back to Lagunas to his waiting family. Half an hour later, our man arrived on his bicycle.

His name was Esteban Choque. He lived with his wife and young son, and derived his living from the many llamas and alpacas he raised. Helping the occasional climber bolstered his income, so he welcomed our presence. A large flat area sat amongst his several rough buildings – we could camp there if we wished.

Once we had pitched our tent, it was time to eat. We wanted to cook a big hot meal but our stove wouldn’t start – there seemed to be some problem with the fuel, it just wouldn’t ignite. After due consideration, we concluded it must have been something like lamp oil. We were using an MSR mountaineering stove, the standard for climbers the world over. It had the advantage of being able to use almost any kind of fuel – white gas, low-grade kerosene, automobile fuel, Stoddard solvent, aviation gas, diesel #1 and naptha. What’s more, it worked well at high altitude, so there shouldn’t have been a problem. Unless, of course, the fuel itself was somehow insufficient.

As we sat munching granola bars and the like, Esteban took note of our plight. He asked if car gasoline would work, and offered to ride his bicycle the 5 km to Lagunas to get us some. This was a funky old Chinese bicycle with a brand name of “Flying Pigeon”. We gave him money for it, and something extra for his effort, and away he went. This was one cold and windy place, at an elevation of 13,710′. I pity the fool who suffered severe altitude sickness here, such as pulmonary or cerebral edema, as the only way to alleviate the symptoms is to drop to a lower elevation quickly. Well, there is no lower – it’s all high, very high, for a long way in every direction. The Altiplano is a great place if you like high elevation.

We crawled into our sleeping bags and tried to get some sleep. Later on, we could hear people talking and dogs barking, allowing a fitful sleep at best. The next morning, we awoke at 6:00 am and started to get ready. The señora brought us the gasoline and suggested leaving at 10:00 o’clock rather than 8:00, which was fine by us – we went back to sleep. Later, when we got up, we tested the gas in our stove and it worked like a charm. The hot chocolate tasted good, along with the bit of food we forced down. Juan, their young son of four years, watched us prepare our gear and asked lots of questions. I don’t know how many climbers passed through their property, but the boy seemed fascinated by our equipment.

Once we had our gear organized, Esteban loaded it on to two donkeys and we were all set to go. The next part of our adventure was set to begin, our attempt to climb Nevado Sajama.

Please stay tuned for the next part of our adventure, entitled “Nevado Sajama”.

Please visit our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690