Sajama has the label of nevado because it is permanently covered in snow and ice. Bolivia’s highest mountain, its elevation has been recently revised to 6,550 meters or 21,491 feet. It sits in Sajama National Park, close to the border with Chile but wholly within Bolivia. As the Desert Mountaineer, I was in my element here, as the park receives a scant 3.5 inches of rain each year. The name means “exiled” in the Aymara language, and originates in a creation legend. There was a war between the mountains and the Creator and, as a result, Sajama was exiled from the other high Bolivian peaks such as Illimani, Huayna Potosí, Ancohuma and Condoriri.

Sajama was first climbed, after several attempts, in 1939 by Joseph Prem and Wilfred Kuehm. It is the 15th-highest peak in the Andes Mountains. Not to diminish Sajama in any way, the Andes is an amazing range filled with very high peaks. It has an amazing 51 summits higher than Mt. McKinley, the highest we can boast of in North America. If we count the peaks over 6,000 meters, we find a whopping 120 of them! But Sajama is spectacular, and is regarded as one of the world’s most beautiful mountains.

Here’s another interesting bit of trivia. Some years ago, FIFA decided that it would no longer use the city of La Paz as a location to hold international football (soccer to our norteamericano readers) matches because of its very high elevation. So, in August of 2001, two teams of players made up of Sajama villagers and Bolivian mountain guides played a match on the summit to show that altitude itself is not a limitation to physical strain. It was the world’s highest football match.

Once Brian and I crawled out of our sleeping bags, we fired up the MSR stove with the automobile gasoline as fuel, and it worked like a charm. We made some hot chocolate and nibbled a bit. Esteban and his wife loaded all our gear on to the backs of two donkeys. A third, unladen, came along as well. Esteban and his three dogs rounded out our party. Talk about a couple of tourists, all Brian and I had to do was put one foot in front of another and walk in a straight line, carrying nothing but our cameras. Speaking of straight lines, the path we took east from Esteban’s place was straight as an arrow and went for miles.

An archaeological feature of the area is something known as the Sajama lines. Click for a link to read more about them. I mention it here because, on the morning of Sunday, June 23rd, in the dead of winter, Brian and I were setting out along one of these lines. We walked up a long, gentle slope and could feel the exertion even with no packs. At 14,275′ we stopped at a junction to rest a bit. We noticed that Esteban was taking coca leaves from a bag he carried and putting them into his mouth. He described the benefits to us, but I think you might find this link interesting to better understand the actual benefits of the coca leaves.

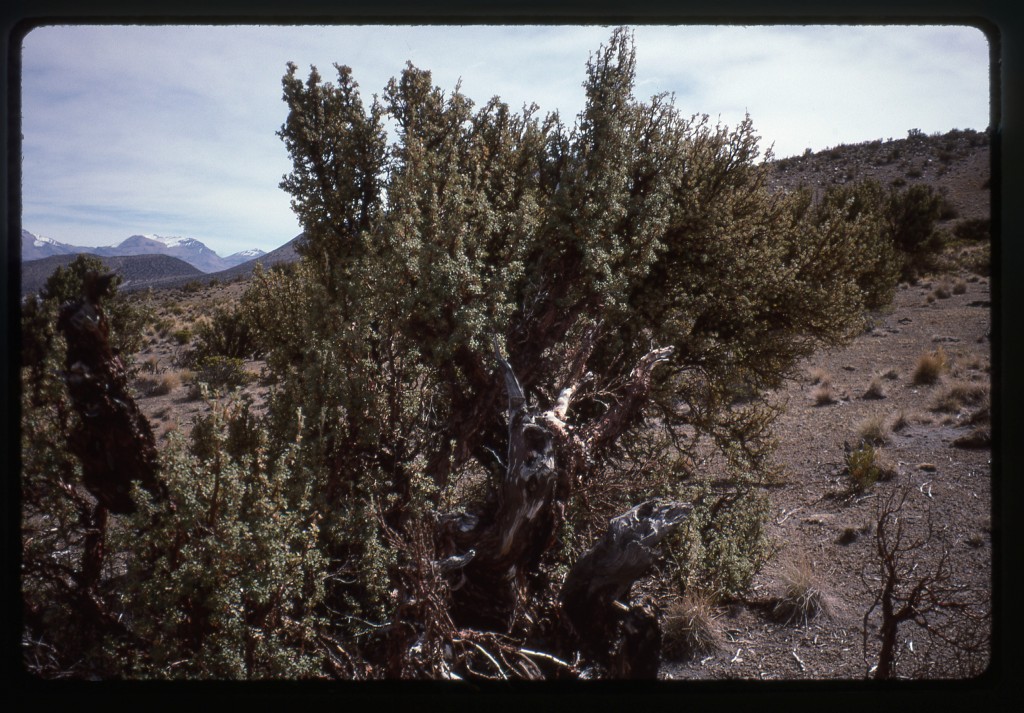

After a short rest, our little party continued, walking up a gentle valley. When we finally reached an elevation of 15,370 feet, Esteban signaled a stop – this was the spot climbers used as a base camp for the southwest ridge. What a place, what a view! Sajama towered over everything, the center of our local universe. Even at this elevation, plants grew, and some of them were very interesting. Right beside camp were several queñua trees, Polylepis tarapacana. These hardy trees live on the mountain up to an elevation of just over 17,000 feet, the highest that any trees grow in the entire world.

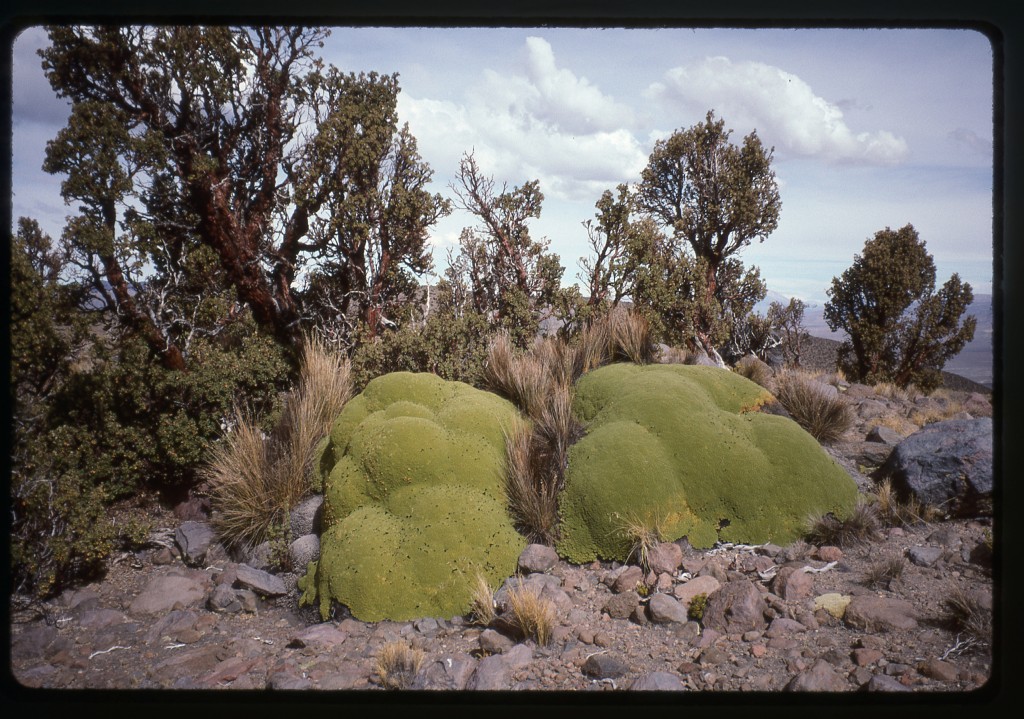

Another curiosity was the yareta moss. It grew all around the area of camp. Here is a picture I took.

There is more to be said about this fascinating plant, so I am including a link here which explains it better than I might.

While we talked with Esteban, one of his dogs ran off to chase a vicuña. Here, this rare animal is at the top of its elevation range. He said there were plenty of them in the area. Pumas too. Before long, he said he needed to leave, and wished us luck. We asked him to come back in three days to take our gear back out to his place. He was fine with that.

We set up the tent and cooked a lot of food – our only proper meal since leaving La Paz. I’d had a headache all afternoon – not bad, but there. When you consider that it had been little more than 48 hours between arriving in the country and getting to this elevation, many might say we were pushing our luck with the altitude. It certainly flew in the face of the conventional wisdom about gaining elevation slowly in order to acclimate safely. It was windy and +35 degrees F. at 5:00 pm when we went to bed.

That was one long night – we didn’t get up until 8:00 am. After brewing a big pot of coca tea and eating something, we headed north out of camp in light snow flurries. Our idea was to get used to the altitude by wandering around, going up higher to check out the route. Soon after leaving, we saw three more vicuñas and even heard them calling. Another rare treat was seeing an Andean condor, a bird with an enormous wingspan that can live up to 100 years of age.

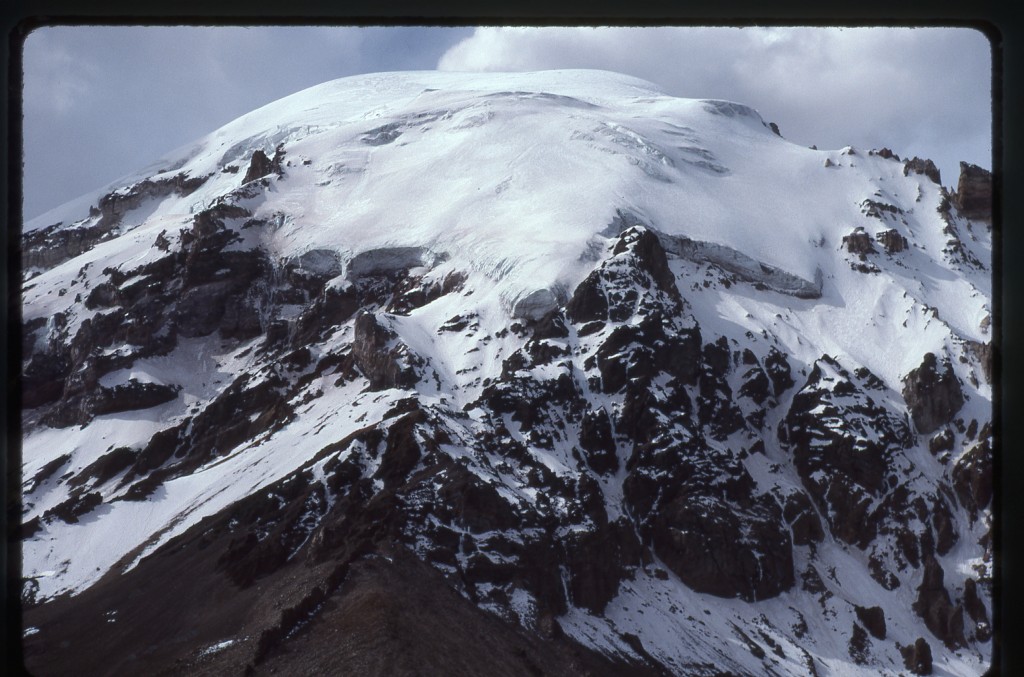

A lot of clouds were drifting through as the morning progressed. We kept eyeballing the high camp area – just above it was where the glacier started. Normally, this would be covered with a layer of snow. Although steep, probably 50+ degrees, it would be straightforward enough. We could tell, even from 2,000 feet below, that the snow had all melted away, revealing hard blue ice. I had talked Brian into leaving our ice tools and hardware at home, that Sajama would be a cake-walk, and all we’d need would be regular ice axes and crampons. Hmmm, in retrospect that may have been a big mistake.

We needed a better view, so we continued on to the pass at the head of the valley, then on up to the summit of Cerro Chucarero, elevation 17,081 feet. This was a great vantage point – with our binoculars, we glassed the entire western side of the mountain for a long time. No alternate route came to light.

Esteban had told us that, in August and September, the snow would melt and bare ice would be exposed directly above the high camp. At that time, climbers rope up and protect the route – that time appeared to have arrived early this year. And there we were with no rope or hardware. It seemed our goose was cooked – we just couldn’t see risking it without proper gear. The idea of relocating to another part of the mountain to try a different route didn’t appeal – it would mean starting over with no knowledge of another route. Due to my short-sightedness, our quest for Sajama was over.

Back we went, down to the saddle, then down the valley we had ascended. On the way, we were lucky enough to see a mountain viscacha, a creature that is related to chinchillas but looks like a rabbit with a long tail. There was also plenty of fresh vicuña poop and tracks everywhere. It really was a beautiful valley, a magical place indeed. although it was with some sadness we walked back to camp. That evening, it was very windy and +25 degrees F. We drank the last of our bottled water – fortunately, a tiny brook ran past our tent. Brian had brought halozone tablets, which we now used to purify all the water we needed for drinking and cooking. We ate quickly and crawled into our sleeping bags. Tomorrow, we’ll go down to Esteban’s place and figure things out from there.

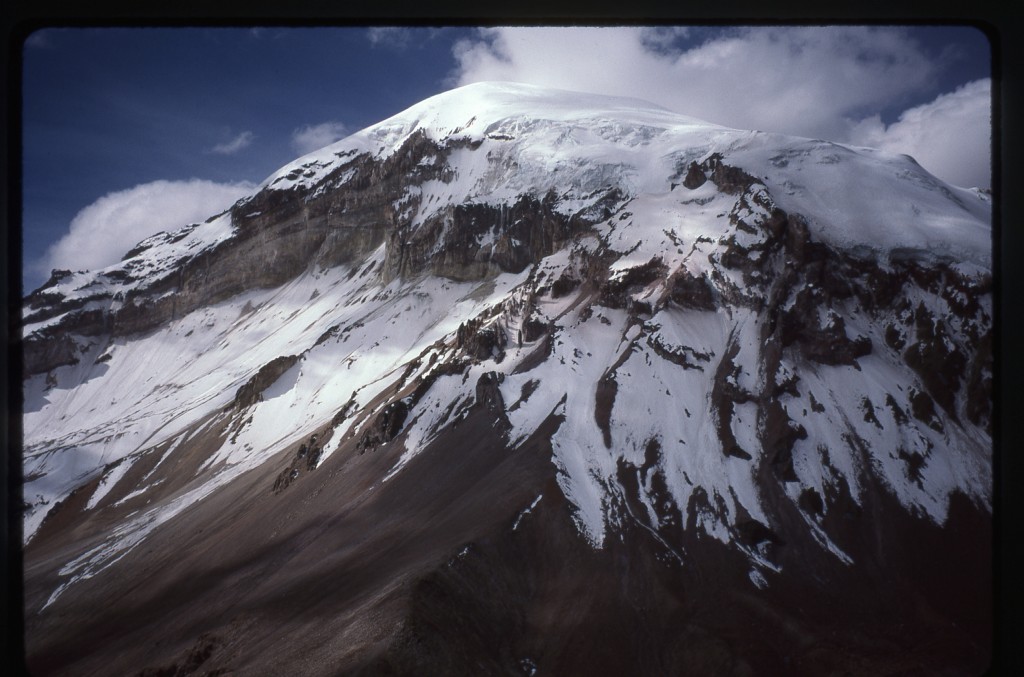

At about 8:00 am, we got up. There was ice on the inside walls of the tent, and our water bottles were frozen good and hard. We packed everything up, leaving nothing behind. Some of what we were carrying out was stuff we brought in only because the donkeys carried it. About three hours into the march out, we ran into Esteban – he was walking 10 km. to see some of his llamas. We spoke at length with him. Since we asked, he told us that the north-side routes on Sajama were more dangerous than the southwest side we had planned on. We also asked him about the possibility of getting into the Parinacota-Pomerape saddle to attempt one of those volcanoes on the Chile-Bolivia border. Here is a photo taken a few days earlier.

He said that it was 25 km., or about 10 hours, from his place to the saddle (17,553′). Also, that the base camp was about 1 1/2 hours before the saddle itself, because pack animals cannot negotiate the rough ground the last part of the way. No snow or water at the saddle either, so it has to be packed in. Usually, maybe, but last night snow had fallen to well below the saddle. At our camp last night, the little stream froze, and our water bottles stayed frozen all this day. We thanked him for taking the time to talk to us about these options and promised we’d discuss it. Taking our leave, we walked the rest of the way to his ranchito. Nobody was there, so we sat around for two hours.

Maybe we’d go back to Lagunas and then into Chile for a few days. The wind kept getting stronger. I had a small mountaineering wind gauge with me which could register wind speeds up to 60 mph, and the wind was so strong it was off the scale. Esteban’s wife returned, and we bought a lot of alpaca wool gloves, hats and socks from her. The wind was so outrageous that we asked her if it would be possible to stay in one of the several small buildings on the property. She led us to one and said we could stay there – it was cold, dark and dusty but at least afforded us shelter from the wind. Once inside, we cooked a bunch of food and felt better. It was so windy and cold outside that it was a misery even going outside to pee.

Esteban returned. He is one tough hombre – today he walked 20 km in sub-freezing temperatures, nearly all of it over 14,000′ elevation, in sandals. When it gets stormy like this, he informed us, it can last for 5 days. We told him we’d decided to move on in the morning and he said we were wise to do so. One of the buildings on his property was small and modern-looking, like a little casita where you could sleep and cook. We thought that he, his wife and son probably lived there, but no – it was to rent out to climbers who were there and needing his services. Here is where they themselves lived.

They had many llamas and alpacas, which were their mainstay. People from other countries might feel that they lived in poverty, but I admired their industriousness and entrepreneurial spirit, and envied much about their lifestyle. He spoke three languages – Aymara, Quechua and Spanish. As we were settling in for the night, we noticed a cat in the little building we occupied. Not your average cat, though. It didn’t look like anything we had ever seen before – no wonder, it was an Andean mountain cat, Leopardus jacobita, and it had been killed and stuffed.

Brian, the cat and I stayed up very late, to the ungodly hour of 7pm. It was a poor night’s sleep, however. The roof of our structure had several gaps in it – as a result, all night long, frozen specks of dust, ash and dried llama feces settled on our faces. The wind roared outside with hurricane force, keeping us wide-eyed and wondering throughout the night.

Stay tuned for the next installment of the story, called Crossing the Border into Chile.

Please visit our Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690