It was another long night, but I slept fairly well. In the morning when I awoke, I felt no adverse symptoms of altitude. When daylight arrived, I dreaded getting out of my sleeping bag. The sun’s rays hadn’t reached our side of the mountain yet when I went outside, and it was bitterly cold. Firing up the stove was the first thing I did – we had plenty of fuel, but no water. What was left in the pot was frozen solid, and it was so cold we didn’t want to cook any food. Instead, we ate canned sardines and, even better, date bars that Brian had brought all the way from Toronto. Then, we spent a long while melting snow, enough to fill a 1 1/2 liter bottle. I guess you could call it water, but it was disgusting, a brownish color and foul-smelling, probably from the unwashed cooking pot..

Breaking camp, we headed down the mountain – it didn’t take long to reach easier ground. We kept shedding clothes, layers of them, as we warmed up, even though it was still below freezing. In about two hours, we reached the end of the road where we had been dropped off two days earlier.

I don’t know how far we walked along that dirt road, but it was several kilometers through that surface-of-the-moon terrain. My feet were killing me – those double boots with a rigid sole were never meant to be used for walking on roads. To this day, I don’t know how Brian did it – those same boots are the ones he wore 24-7 for our entire trip. Eventually, we reached the paved highway – praying that someone would stop and give us a lift was to no avail. At around 3:30 p.m., we stumbled into the refuge at Chungará. Words cannot explain how good it felt to take those boots off – a few blisters were the only lasting effect.

Once we settled in, an Australian couple befriended us – they were cycling from Arica to La Paz. What a neat adventure. Others at the refuge told us that the two Americans never did summit – in fact, they didn’t get much higher than the tent-site we had spotted a few days earlier. They had already returned to the refuge and headed for parts unknown. Arturo, the guardaparque, had watched us climb through binoculars and said he could easily follow our progress. Columba and Mark showed up. They had been out hiking every day, and had seen us from the vantage point of the lakes near the village of Parinacota. They had been to the southwest of the peak, so they had a perfect view.

Man alive, it was good to take a hot shower and put on clean clothes. We felt almost human again, especially after eating huge amounts of food. It was fun to stay up late, talking with all the foreign visitors and drinking good wine. After exchanging addresses, we turned in – it was going to be hard to leave the camaraderie of this place.

July 1st – it was Canada Day. Getting up at 6:00 a.m., we packed up our stuff and paid our bill. Without eating anything, we hauled our gear out to the highway in front of the refuge. It was cold and windy as we stood on the side of the road, singing songs from the Beatles’ White Album. Not 20 minutes passed before an 18-wheeler stopped as we thumbed a ride, the first vehicle along. The driver was a Bolivian man from Oruro, a pleasant fellow named Mario. In Bolivia, a common mode of getting around is hitching a ride with a trucker and paying him a fee.

Within a few minutes, we arrived at the Chilean customs station with the name of Chungará. It wasn’t really open yet, so we had to wait a bit before Mario had all his paperwork finished. Brian and I had our passports stamped and we were ready to go. This is common practice at many South American border crossings – one procedure to leave the country you’ve been in, then another to enter the one to which you’re heading. It can be quite time-consuming. We gave a ride to two other truckers the short distance to the next customs point, the Bolivian one called Tambo Quemado. For some reason, that whole affair took hours.

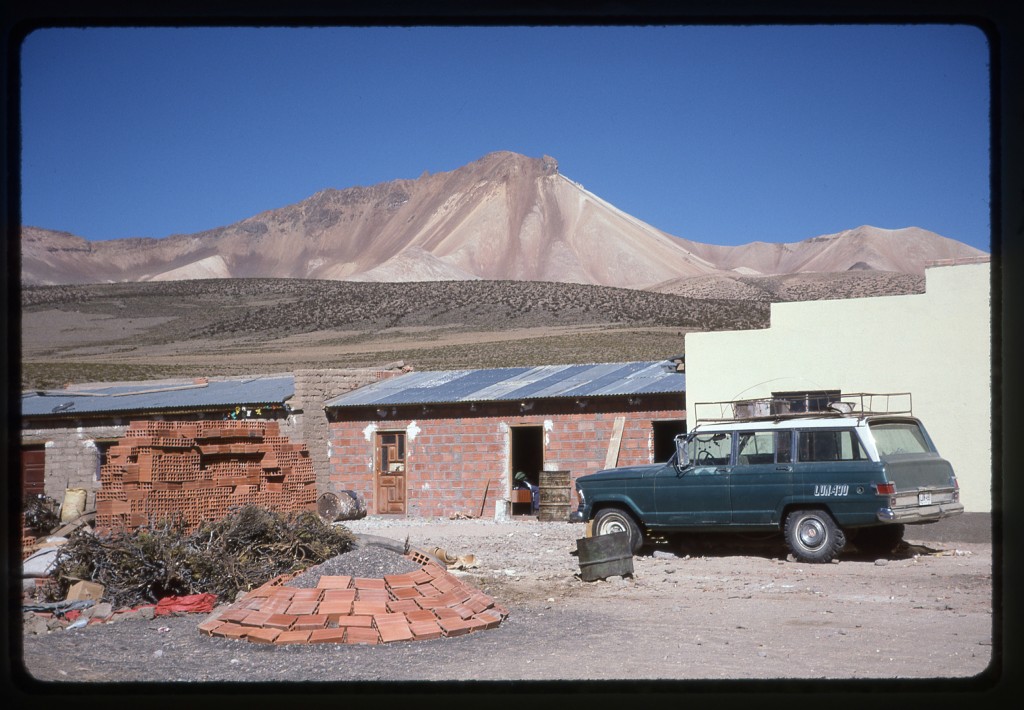

We offered to buy Mario breakfast, but the only place we could find was a creepy dimly-lit joint that was freezing cold (you have to remember that this forgotten outpost of humanity sits at over 15,000 feet above sea level). The white building in this next photo shows the place, with 19,000-foot mountains out back.

The crone whose place it was informed us that the only thing she could feed us was soup. We were in no mood to argue, so we told her to bring us three bowls of her finest. I remember it to this day. First of all, it was barely warm. It had a bit of rice, and some little brown potatoes. South America is where potatoes originated, and in rural areas like this, people put them on their roofs to naturally freeze-dry. But the best part, at least for me, was the chicken foot in my bowl. Yum. This meager fare was all there was, so we ate it up. Ten days later, back in our respective homes, Brian and I were both sicker than dogs with the same symptoms. I had phoned him to discuss it, and we both agreed that the cause was that memorable soup.

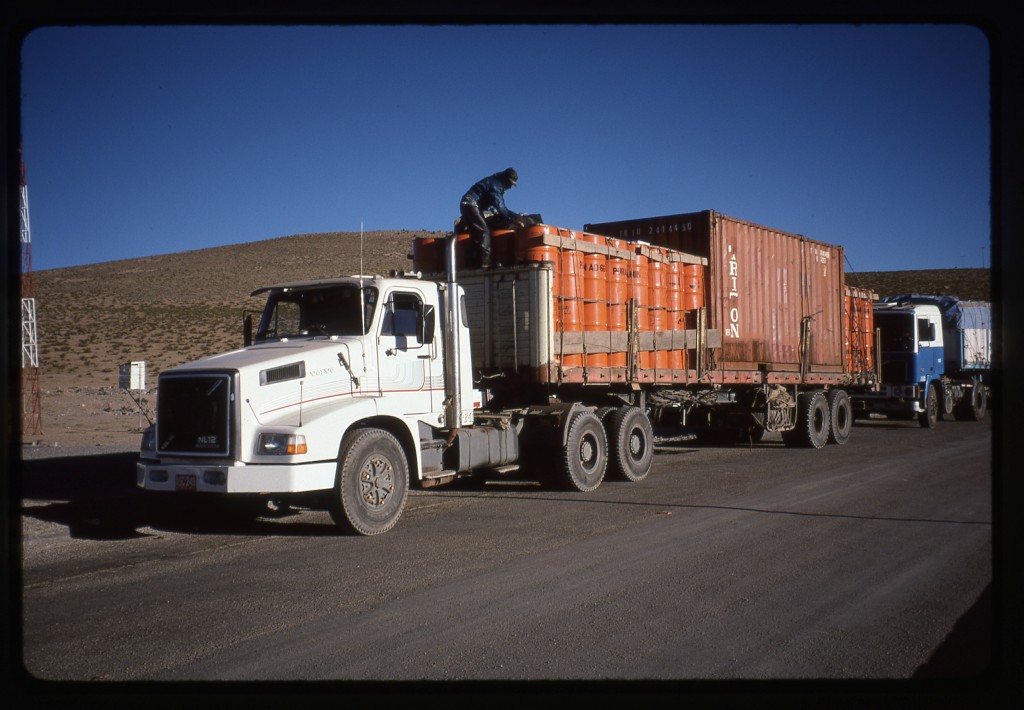

Once done, Mario spent time talking with others, plenty of whom wanted rides, but we had no more room. Finally, we boarded the truck again and headed out. The rig was a 1990 Volvo 400-horsepower diesel, its main cargo a huge shipping container. We asked what was in it, but Mario said he didn’t know – his job was to deliver it to its destination, he didn’t even have the means of opening it. He was also carrying several barrels of some kind of concentrate, and our gear was stashed in amongst them.

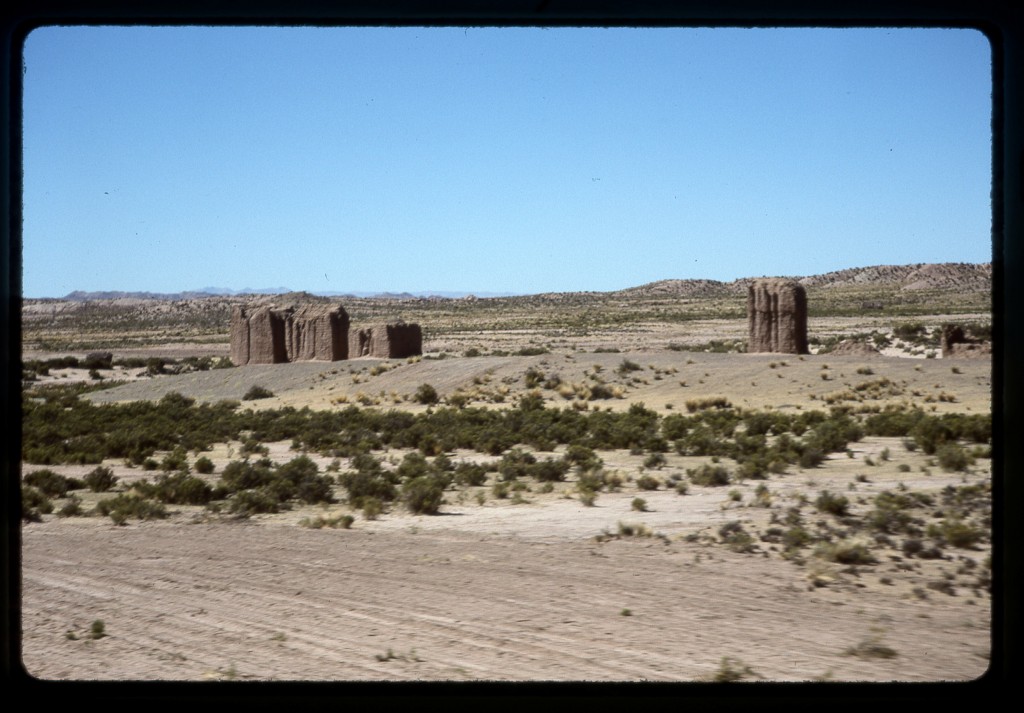

Riding in the truck was very comfortable – there was a sleeping area behind the seats. I talked a lot with Mario as we drove along through river valleys and eroded hills. This view was taken through the truck windshield.

From the truck, we spotted some towers – Mario said they were called chullpas. To learn more, check out the link I have provided here. It would have been great to have had more time, to explore them a bit.

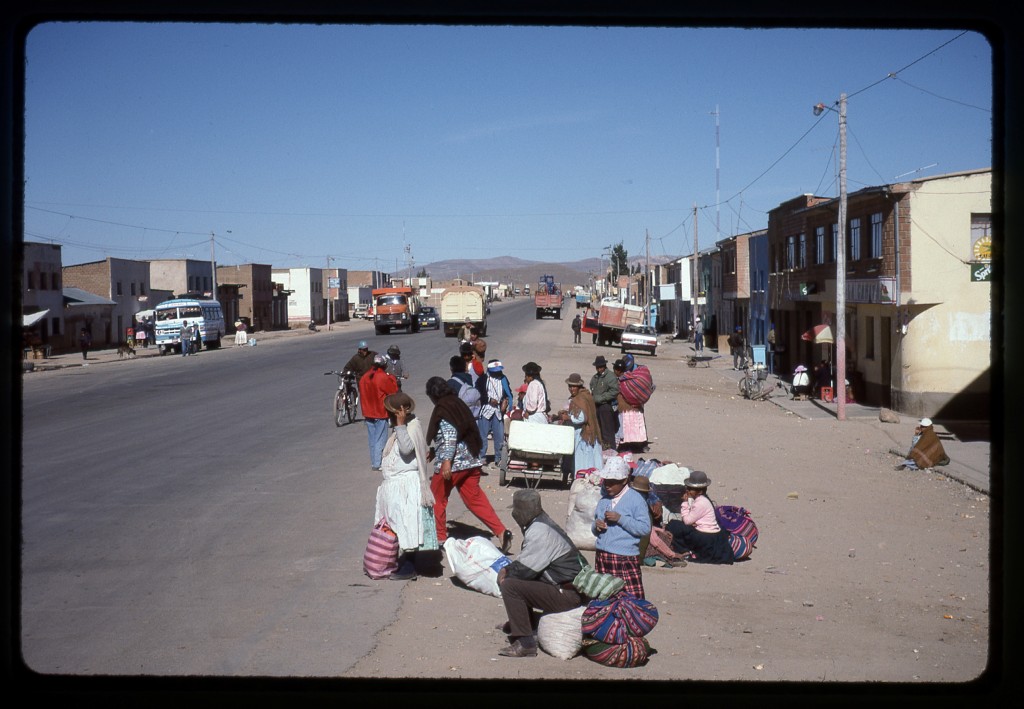

By about 2:30 p.m., we arrived at the town of Patacamaya. Mario parked his rig along the main street and waited with us while we caught a bus. About every 5 minutes, one came along, but as soon as it would stop, people would rush on before us and grab all the seats. Finally, we got on one. Mario had asked us for 50 Bolivianos each for the ride with him, which we gladly paid.

The hour and a half bus ride to La Paz cost us 6 Bolivianos each. I ended up sitting in a seat wet with baby pee, just my luck. I remember a mother lying down on the floor of the bus and nursing her baby en route. A lot of people got off at El Alto, and not long after that we arrived at the main bus terminal in downtown La Paz. A taxi fare of 6 Bolivianos got us back to our old hotel, the Hostal República, and our old room, #306.

It felt good to be back. After a shower and a change of clothes, we headed out on the town. It was our good fortune to stumble upon a pizza joint that made a really good pie – we ordered and consumed a huge one, and washed it down with plenty of ice-cold Pacenas to the accompaniment of Beatles’ music. La Paz is a very hilly city with some steep streets, and our walk back to the hotel was up some of the steepest. We steamed up them, feeling very fit from all the recent climbing at high altitude. To bed by 10:00 p.m. Transportation back to the capitol had gone very well for us today, and we felt mighty pleased.

Stay tuned for the final installment of this story, entitled Lake Titicaca.

You can also visit us at our Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690