Deep in southwestern Arizona’s desert country sits a remote mountain range called the Agua Dulce Mountains. This range lies just north of the Mexican border, and can only be approached by a long bumpy drive along a road called the Camino del Diablo (The Devil’s Road, aptly named). It contains 22 summits, and a best search of mountaineering websites showed that 13 of them had not been previously climbed. That might leave most climbers incredulous, but the simple fact is that there are plenty of peaks in remote desert areas that have not been visited by anyone. They are just too remote, too difficult or too dangerous to tempt most climbers. There’s a great mountaineering website called Lists of John, which lists over 84,000 summits in the U.S. Something quite surprising is that over 37,000 of them do not appear to have recorded ascents. Granted, that’s based only on the records of that one website, but LOJ boasts an impressive list of over 2,200 peakbaggers who are out there climbing everything in sight.

I had first visited the range back in 1988, but that was solely for the purpose of climbing the range highpoint. In the intervening years, the very thought of all those peaks waiting out there, unclimbed, made me a little crazy. Finally, a week of furlough from my job made up my mind for me. Jake was willing to be a part of this adventure, so away we went. And now here we were, three full days invested in the project and camped less than two miles from the Mexican border. With seven peaks already under our belts, we had made a good start but wanted more. Another beautiful sunset and we settled in for the night.

We spent a quiet night, but the next morning dawned cloudy, much to our surprise. Setting out early, it was a short walk over to our first climb of the day, Peak 1630. Via the west ridge, we climbed through huge granite boulders, wondering if it would rain. Virga was seen falling in several places near us, but I don’t think we felt above ten drops. It didn’t take an hour to reach the summit, where we once again left a register.

I suggested to Jake that we could try a different descent route, so we dropped off the south side. It was steep, but, with fewer cholla to avoid, it was going pretty well. Most of the way down, during a brief rest, we plainly heard the sound of rocks rolling down the slope above us. We looked up and, much to our delight, caught sight of a huge desert bighorn sheep ram.

It moved fearlessly across the mountainside above us, and then we noticed four large ewes following. I was able to take a movie of them, and if you click on this link, you can watch it on YouTube.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HvhKR7NzyCg

It’s not every day you can see bighorn sheep in the desert. Although we continued to see sign on most of our peaks, this would turn out to be the only actual sighting. Once down the mountain and back at our gear, we continued southeast, talking excitedly about the sheep. Less than a mile later, we came upon the skull.

That certainly stopped us in our tracks. Once we got over the shock, as much as was possible, and had documented it as best we could, we carried on to our next peak. However, the surprises weren’t done yet. A thousand feet from the skull, we walked into a group of 20 senita cacti. These are very rare in the U.S.

The tops of these are distinctive.

A botanist I know at the University of Arizona was very interested to learn of this stand of senita. We reported all the details to him upon our return.

What a day – in the space of an hour: sheep, skull, senita. Triple S. And it was barely ten o’clock. Hard to imagine what else could be waiting for us. A mile later, we stood on the top of Peak 1443. Not to put too fine a point on it, but it felt good to leave another register. We didn’t linger, and soon headed back down to the desert floor, past the senita and the skull, past the mountain with the sheep and farther west to arrive at Davidson Canyon. We set up camp there, then headed west up another wash with day packs for our last one of the day.

Peak 1510 was the perfect ending to our day. We had had plenty of excitement earlier, so it was nice to walk up this peaceful valley. The upper slopes on the east side of the peak were steep and made us pay close attention. We stood a mere mile and a half from the border, and the view towards Mexico showed the harsh desert below. In the next photo, Cerro Pinacate is plainly seen on the horizon.

The summit was a tranquil spot, and after preparing a register, we hung around for a while and soaked up the view. Our descent route was steep and loose, and further complicated by large numbers of teddy bear cholla cacti. At a particularly bad spot, a rock came loose and tumbled down the slope and struck several of them, mowing them down and creating a narrow lane for us to pass. Fear not, those of you who don’t know this cactus. There are approximately a hundred trillion bazillion of them in the Sonoran Desert, and a few less won’t have any environmental impact. Besides, when struck, they explode into dozens of smaller pieces, each of which will quickly grow into a new plant. By the time we climbed down and walked the wash back to camp, it was late and time to build our usual campfire. We now had ten peaks under our belts, but we weren’t done yet.

We awoke before dawn – it was 40 degrees – and headed up Davidson Canyon to climb the next peak to the north. It was the work of less than two hours to climb up and back down Peak 1565. Once again, we left a register on its summit. There was one more in this area we wanted to do. Peak 1550 was a small bump just south of Papago Mountain, and it was an even quicker round trip. Were we able to leave another register on its summit? Well, duh!

There was one more peak to do, but it was a long way off. It was less than five miles to the Mexican border by heading back down Davidson Canyon, and by the time we got there it was still morning. For some reason, I expected to see a simple barbed-wire fence, so imagine my surprise when this vehicle barrier confronted us. It stretched to the horizon in both directions. Made of very thick steel, we later learned that it is embedded twenty feet into the ground. A fence for the ages. It certainly will stop any vehicle, but those on foot can still easily cross, like our friend whose skull we had found yesterday.

I love to see border monuments, and this stretch promised to deliver. As we continued east, the first one we encountered out on the flats was number 177.

The next one sat on a ridge and looked out a long way along the border.

And, finally, we came to number 175. It was one of the tall, early ones.

On the steeper bits, the vehicle barrier was what they call Normandy-style.

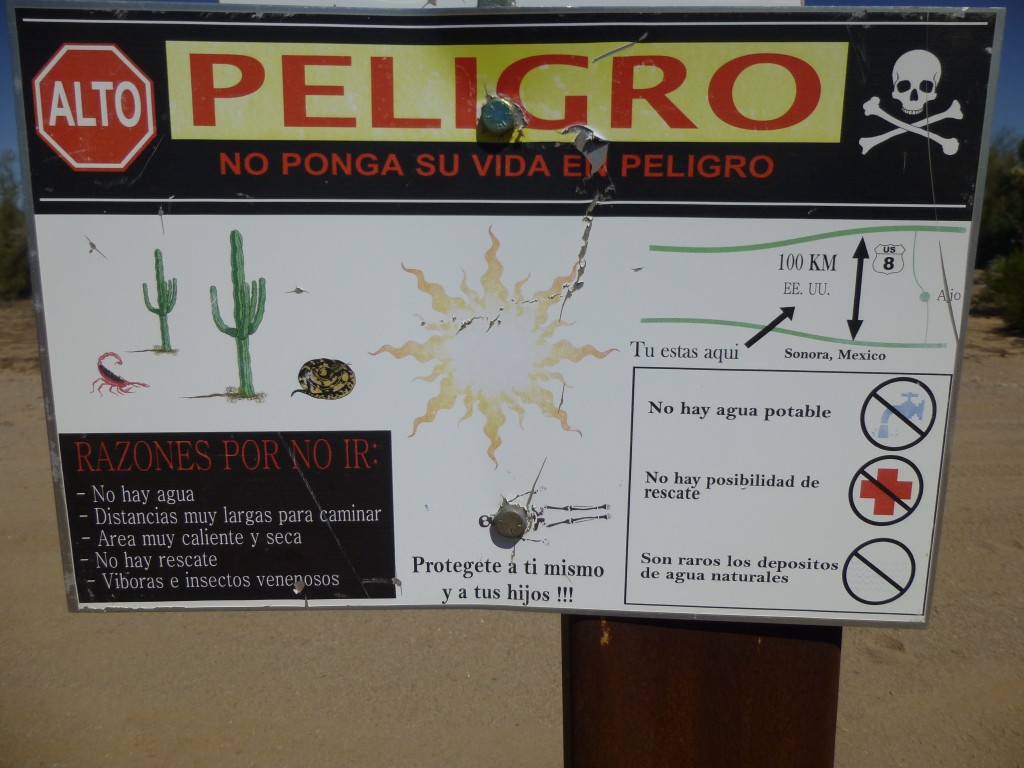

We had noticed that at frequent intervals, this sign was attached to the barrier, so those approaching on foot from Mexico would pause before making the attempt to cross into the U.S. Of all the border warning signs I’ve seen, this one was the most graphic. I love all the warnings: skull and crossbones; scorpion; rattlesnake; blazing sun; skeleton on the ground; no drinkable water; no chance of rescue; “don’t put your life in danger”; “protect yourself and your children”. It points out that Interstate 8 (a common point for undocumenteds wanting to get picked up) is 100 km to the north. True enough, but that is air distance – to walk it, you’d put in far more than that.

Once east of monument 175, the rest of our plans depended on finding a faint track heading north. Back and forth, we missed it several times, until Jake said the GPS had us right on it, so north we went. Within a few hundred yards, there it was. You had to use your imagination, but it continued in the direction we needed. The desert was filled with both saguaro and organ-pipe cacti, and was still as death as we moved on. The route continued up a steep rocky wash, then emerged at Agua Dulce Pass. Hallelujah! I had stood here only once, 25 years ago, and the years had not been kind to the road.

It was uncomfortable, standing there in the hot sun, so we walked downhill on the north side of the pass to camp in the shade. For some reason, many bees found us and decided to land on our gear and make us nervous until nightfall. As we sat there, enjoying a well-deserved rest, a loud noise approached from the west and its source came into view. A large plane, followed closely by two huge helicopters, flew by. Military, no doubt, it looked like they were practicing mid-air refueling. The photo is highly magnified. Soon after, we saw three more similar sets of aircraft fly over, heading east.

Here is a short video of the helicopters flying over us:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZHTU8Ug9Fok

Exhausted, we turned in early and slept well. Up at the crack of dawn, we climbed our last mountain directly uphill to the east of camp. Peak 2280 was steep and loose, with some more stable rock near its summit. Once on top, we could look southeast over the last stragglers of the Agua Dulce Mountains.

We were done, it was all over but the shouting. After our cairn and register, we dropped back down to the road and packed up. Ten miles later, all downhill following the old road, we emerged at the Border Patrol station called Boundary Camp on the Camino del Diablo.

“Stick me with a fork, I’m done” seemed the most appropriate thing to say at the end of our journey. A total of 13 peaks climbed, 10 of them never done before, over a six-day period. A lot of hard work, but I’d do it again in a heartbeat.

You can also visit us at our Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690