I’ll bet you’ve never heard of the Telkwa Range. Okay, maybe if you live in west central British Columbia you have. I have an excuse – I worked there the entire summer of 1968. To this day, several highlights of that season still stand out in my mind. Here’s a for-instance:

There was this fellow on the crew, name of Don. His image is forever burned into my brain for one main reason – he had a big gun, the biggest I’d ever seen. That’s pretty unusual in Canada, a country where very, very few people own a handgun – it’s always been that way. One of the few reasons, at least back then, that allowed you to legitimately own one was being a prospector. I guess the logic was that you might need it to defend yourself against ferocious beasts in the wild. I spent many days prospecting with Don out in the bush. Our chopper would drop us off out in the middle of nowhere, we’d prospect all day, then get picked up at day’s end. Don was a moody fellow, often quiet, but otherwise inoffensive. That fall, after we had all returned to Vancouver, I heard a story that gave me pause. Turns out Don was up in Whistler one afternoon and asked a store clerk to cash a personal check for him. When the clerk refused, Don calmly walked out to his car, got his gun, went back into the store and blew the clerk’s brains out. Dang, to think that I had worked with the guy, just the two of us, all day long, on many occasions. I’m sure glad I never pissed him off.

After several weeks of moving around prospecting, we finally settled in to our bush camp for good, eight miles south of the village of Telkwa, at the end of a dirt road. It was a collection of large tents with plywood floors, complete with wood-burning stoves – quite comfortable, actually, plenty adequate for a summer field season. My boss was this jerk from back east, an arrogant bastard who did everything possible to make my life miserable. One of the few satisfactions I had was getting high once in a while with some of the other young guys on the crew – we’d sneak out into the thick bush that surrounded our camp and roll a few joints.

Oh yes, I was telling you about the Telkwa Range. There was a group of mining claims deep in one of the northern valleys of the range. We held an option on these, so it meant spending a lot of time there trying to prove their worth. There was no road nearby, so our helicopter was heavily relied upon to move us back and forth from our camp. A problem we encountered early in the season was the heavy snow cover that lay upon those claims. It’s hard to geologize when you can’t see the rock, so one of the guys came up with a bright idea. There was a small colliery a short way back down the road from our camp. We made a deal with the mine – we’d show up with burlap bags and shovel them full of coal dust. What a frickin’ awful job that was – it’s a miracle we didn’t all get black lung disease from doing it. Once we had a sufficient amount of it, we flew over the snow on the claims and dropped it from the chopper, trying to make it spread out and cover as much area as possible. It worked! The snow melted much more quickly over the dusted areas and we got down to business.

Studying that claim group didn’t take long, only a few weeks – we essentially wrote it off as unpromising. So, the bosses, such as they were, decided we’d spend the entire rest of the season right there in the Telkwa Range. A lot of our time was spent flying from base camp, getting dropped off and prospecting all day. This gave me a chance to explore many valleys and ridges throughout the range, and those were fine days indeed. Most of the areas where this geological exploration occurred were above treeline, and since that is my favorite mountaineering environment, I was in hog heaven.

As the summer progressed, we started to explore from fly-camps. To set up one of these, our chopper would ferry several loads to a spot where we would put up a strong, spacious canvas tent. That done, we’d then set up the rest of our gear, including a two-way radio powered by a car battery. Sleeping was done on cots in warm sleeping bags. A propane stove would allow us to cook all manner of good food. If bad weather set in, there wasn’t much to do but lay low and read a book until things improved. The one of these camps that I most clearly remember involved my boss and me. There was no love lost between us, and we had not a single thing in common to pass the time. To avoid contact with him, I spent my days heading out alone for long periods. We were camped on a broad ridge above treeline, and all I had to do was step outside the tent and start walking in order to get away from him. I developed the habit of staying out for longer and longer periods of time, putting in some long days.

One day I was in a valley well above treeline, sitting on an outcrop eating my lunch and minding my own business. I saw something moving below, making its way up the valley the way I had come. Lo and behold, it was a wolverine, the first I’d ever seen. Perhaps 200 feet away, it didn’t see me, and I watched it for maybe ten minutes until it moved out of sight. The valley floor was still deep with snow, and the creature was post-holing its way along in a very determined way. It was heading towards the nearby pass and down to the valley beyond. What a treat! I’ve never seen another.

In the course of these ramblings, I climbed a lot of mountains. An incident that still stands out in my mind went something like this: I was by myself one afternoon, climbing up a cliff, a sort of headwall, in a lonely valley. I got way out of my comfort zone and found myself in a desperate situation, afraid to descend the way I had come up. The rock was all wet from a patch of melting snow several feet above me, so it was slippery as hell. I remember to this day being terrified that I wouldn’t be able to climb up and out of the fix in which I found myself – I was scared shitless. Somehow I did it, hanging on by my eyelids, but was praying out loud and crying like a baby as I hauled myself over the lip onto a flat, safe ledge on the snow and heather. I’ve climbed close to 2,000 mountains since then, but it still stands out clearly in my mind to this day, 46 years on, that I almost bought the farm. That fly camp, the one I was in with my boss, was only three short air miles from Mt. Forster, the highest in the range. It was one of the ones I bagged that summer.

Another concern we always had was bears, as they would always come snooping around. A few came to our base camp down at the end of the road. My paranoid, trigger-happy boss shot one of them one fine day. He was pretty proud of himself as he stood over the bloodied carcass – I disliked him even more after that.

During my previous field season, 1967, in far northern BC, our camp cook was an old-timer named Pat Downey. An admitted alcoholic, he had told us his home was a hotel room in Telkwa. Well, it turned out that a few short miles from our camp was the village of Telkwa. The hotel there had a beer parlour, and it was the closest place for us to enjoy a cold one. One day I was in the joint, knocking a few back with some of the guys on the crew, and I remembered that Pat supposedly lived there. I inquired if he was about the place, and was told that, in fact, he was sitting over there in that dark corner, Strider-like. I went over to him and introduced myself. He was three sheets to the wind but still remembered me. We had a nice visit. Sadly, his drinking did him in within a year or so, and the Telkwa Hotel had one more vacancy.

Back in the 1960s, my university had an interesting policy. If you failed a course during the regular school year, but not by much, you could write a make-up exam during the summer. There were various places around the province where one could take such a test, but they were all in cities and towns. Under certain circumstances, an arrangement could be made to sit and write in unusual places. Working out in the wilderness, as I was doing, certainly qualified, so the university agreed to let my boss supervise my writing this exam. The course was optical mineralogy, not one of my favorites, so I knew that taking the exam would be a close shave. I studied all summer, and as the big day approached I found myself in a strange situation. My boss and his wife were staying in a rustic cabin at the end of a road above treeline some miles distant, while I was in the aforementioned fly camp with another of the guys on our crew. Because my boss was miles away, and because our chopper was unavailable at the time, the only way I could get to the cabin was to travel cross-country on foot. The big day came. I left the fly camp early in the morning (that far north, in the summer months, daylight comes early). I headed down a ridge, dropped down into a valley, crossed a creek on a snow bridge, then ascended to another ridge. Once across that ridge, I dropped down a steep snow slope, using ice axe and crampons, crossed another creek, then climbed up to the next ridge,where the cabin was located. The entire trek covered several miles, took four hours, and was all above treeline. I found the cabin, no problem, relaxed a while, then wrote the exam. By some miracle I passed, but just barely. It had to have been one of the more unusual ways any student ever got to write a supplemental exam.

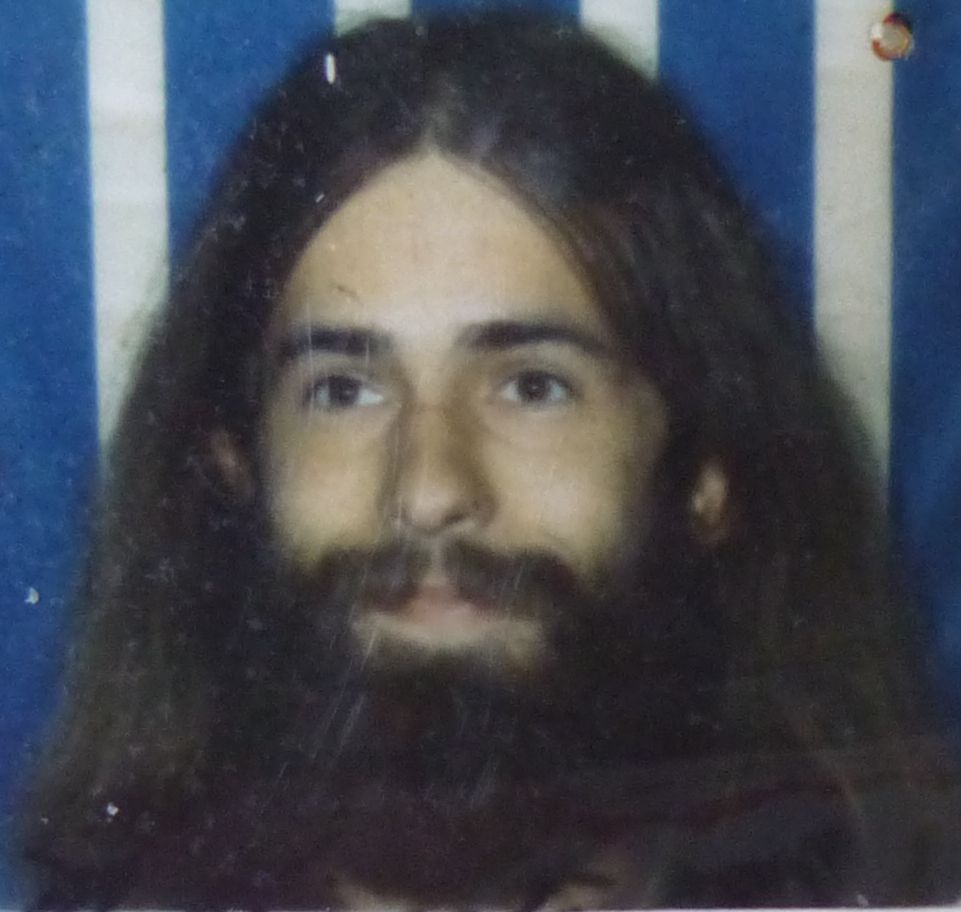

Men working in bush camps such as ours would often become pretty shaggy-looking by the end of the summer, so much so in my case (long hair and beard) that the other guys on the crew took to calling me Barabbas. I don’t know that the biblical character of that name was scruffy, but my co-workers felt the name was appropriate. Here’s a mug shot that was taken when I got back to town.

Because much of the summer was spent above treeline where it was nice and cool, I experienced a lot of snowy days. My diary from that time shows that In May I was snowed on during five days; in June, ten days; six in July, and eight in August.

Came the end of the field season, and it was time to return to the big city. The company would have flown me home, but I chose a leisurely train trip instead. The Canadian National Railway paralleled the Yellowhead Highway, through the city of Prince George and on to Jasper, Alberta, where I arrived at noon the next day. I had a lengthy wait to change trains, so I hustled out and did a bit of climbing during the layover – a great way to spend some time in one of my favorite areas. Late in the day I caught the next train, traveled overnight once more, and arrived in Vancouver. My field season was over, and I was lucky to have spent so much time in a remote, beautiful area visited by so few.

Please visit our Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690