So, when we left off the first part of this story, Andy had just called down to me from higher up on the peak. He had announced that he had good news and bad news. I was ready for some good news, but I dreaded any bad. I replied “Yeah” but didn’t say anything else – I was thinking “Oh, great. I wonder what the bad news is. Hopefully it isn’t too bad”. He then asked me which I wanted first. He didn’t get an answer from me, so he then said: “The good news is that from here, it is only a Class 2 and Class 3 scramble to the top. The hard part is finished”. I shouted back “That’s great, Andy”.

Then he said “The bad news is that you can’t come up the way I did”. I was a bit shocked to hear that. He said that the route he had taken was too dangerous. There were large rocks that were very loose and simply posed too great a hazard, as the simple action of taking up the rope could make them fall, on both me and the rope. He felt that the best thing to do was for me to climb straight up the gully to him and not climb out of it to the right as he had done. He said that it would probably be very difficult and that he would do anything he could to help me. I told him that I was very determined and would do everything in my power to climb it, that I would give it my best shot.

One good thing about our situation was that we could hear each other quite well. I get nervous when I can’t hear the leader, as it makes everything more difficult. Andy was about 80 vertical feet above me, but not visible. I told him that I was concerned that the upper part of the gully was so steep. After all, he had chosen not to climb it because of how bad it looked. I asked him to keep all the slack out of the rope once I got higher up. So, I started up. I was able to move quickly up to the small cave. There was a loose rock the size of a basketball just above it. Andy had gracefully avoided it and moved to the right. I chose to go straight up over it, and it worked. I was able to gain several more feet above that without too much trouble, but then I was on new ground.

Andy couldn’t help me, as he hadn’t been here himself. I soon found that the rock steepened to vertical. It didn’t look that steep from fifty feet lower!! I realized I was in trouble. The holds were small and some of them were loose. I wanted to have a good place to stand so I could rest when I needed to, but the best I could do was find small holds barely big enough to take the toe of my boot. It didn’t help that I was wearing hiking boots instead of rock-climbing shoes. My arms were getting tired really quickly. I have pathetically little upper-body strength, and my arms are very weak. I couldn’t support all of my weight on my toes for long without getting “sewing-machine leg”. And my arms were too weak to hold me up for long. I knew that if I peeled off, Andy would hold me, but with the stretch in the rope I would fall maybe five feet. It would be incredibly hard to regain the ground I would have lost because of how tired I already was. If I fell, the climb would probably have been over for me.

I called out to Andy that it was pretty grim and I was very worried. He couldn’t physically pull me up – I had to do the climbing myself. He told me not to panic, that we would figure something out. There I was with my nose right against the rock and feeling pretty sorry for myself. Andy asked me if I could see a narrow chute on the right side. I said I could. He asked if I was that high yet. I said I was still six feet below it. He said I had to get into that chute by any means, that if I could I would have a safe place to rest. I said I would try. He said I had to keep making upward progress before I got too tired to continue. He then suggested something – he said that we should figure out a signal of some sort. Just before I would make a move, I should holler out “now!” and he would immediately take up all the slack in the rope as I moved higher. I said I would try it – I did, and it worked. Whether I stepped up or lunged up to the next hold, I called out and he took up the slack right away as I made my move. It gave me an important psychological boost. We did that maybe half a dozen times, and then I was at the mouth of the chute! I crawled in on my hands and knees – I could rest – I felt so relieved! The part I had just climbed was about 95 degrees, or about 5 degrees of overhang. For me, this was the hardest part of the climb.

I don’t know what the difficulty rating was, as I don’t have enough rock-climbing experience to determine that. I have done lots of Class 5.7 climbs, and even a few that the leader said were 5.7+, or very hard 5.7s. I do know for sure that it was the most difficult climbing I have ever done, so it was at least 5.7.

Soon, Andy told me that in order to continue I needed to turn around and face out of the chute. I tried but I was stuck. I was wearing Andy’s small day pack with food, water, first-aid kit, camera and a register I had brought along, hoping we would need it. The pack made me too big to turn my body around inside the narrow chute. I informed Andy of this. He suggested taking off the pack and tying it higher up the rope. He lowered down some slack and I attached the pack about five feet above me. He then pulled up the pack and took the slack out of the rope. I was then able to turn around and face out. I had to continue up the face on a narrow ledge, maybe four inches wide, which rose up at a forty-five degree angle on pretty solid rock. It wasn’t too bad, and it got me up to a small tree. From there, I continued up an easier gully, then saw Andy about twenty feet above me and to my left. I climbed up to him and was at his airy perch where he had us anchored.

When you look at the next picture, you will see two lines, one yellow and one orange. Here is what they represent. I took the picture, and am standing below, out of sight, where the yellow line starts. Both Andy’s route and mine are together on the yellow line at the start. The dark hole to the left of the yellow line is what we called “the cave”. Right above the cave, the orange line shows where Andy’s route splits off and heads to the right. The dashed orange line is where he heads out of sight, covers a lot of dangerous ground, then finally re-appears higher up, where the dashed orange line comes back into the picture. All of the photo above the cave is very foreshortened, meaning that it’s farther up than it looks. It’s about 18 feet up to the cave. From where the lines split just above the cave, it is vertical above that point for about 25 feet, then overhanging for perhaps 8 feet more. See where the yellow and orange lines re-join – that is the chute mentioned earlier. The two lines move together over to the left, and that is the narrow ramp. Finally, the two lines move upward together for another 30 feet and out of sight to the large boulder which Andy used as a belay anchor.

Okay, so back to the climbing. I had just arrived to where Andy was belaying me. I was SO relieved! Finally, some safe ground. Andy had anchored us to a large boulder which sat on a small shelf atop a sort of pinnacle. There was room for us both to sit comfortably. He pointed out to me the rest of the route. It did look pretty straightforward. We had to cross an airy gap of five feet (“The Bridge”, as we named it) – it was narrow and led to easier ground. On one side of the gap was a sheer drop down the west face. On the other, the drop down the way we had just come, the southwest corner of the mountain. I asked him for a belay across the gap, which he provided. Once safely on the other side, I unroped and Andy scampered across after me. It was in fact a short climb of Class 2 and some exposed Class 3 to the top, perhaps another fifty vertical feet. We stood on the summit at 2:00 P.M.

Here again are Andy’s words for the last part of the climb:

“With effort, Doug was successful at climbing the direct route top-roped. From our anchor we then crossed a narrow gap in the ridgeline to the summit. Forming the true head of the gully, we called this gap “The Bridge” as both sides dropped steeply, the north being a sheer drop of 100′ or more. After crossing this, it was a very short hike to the summit, unmarred by any cairn or sign of previous human activity. We rappelled off our boulder anchor, down through both gullies, and directly back to our starting point. As the rappel line is more direct than the route used for the lead, a 60 meter rope would likely been sufficient to do the climb and rappel safely down. The overall pitch was hard to protect, and the three pieces of protection placed were marginal at best.”

Finally, here is my take on the last part of the climb:

As we approached the summit, I anxiously looked around for any sign of a previous ascent. We looked everywhere, but could see no indication that anyone had been there before. No rocks were piled up – it was just as Mother Nature had formed it. There was a flattish area about twenty feet long and ten feet wide, and then it dropped off very steeply on all sides.

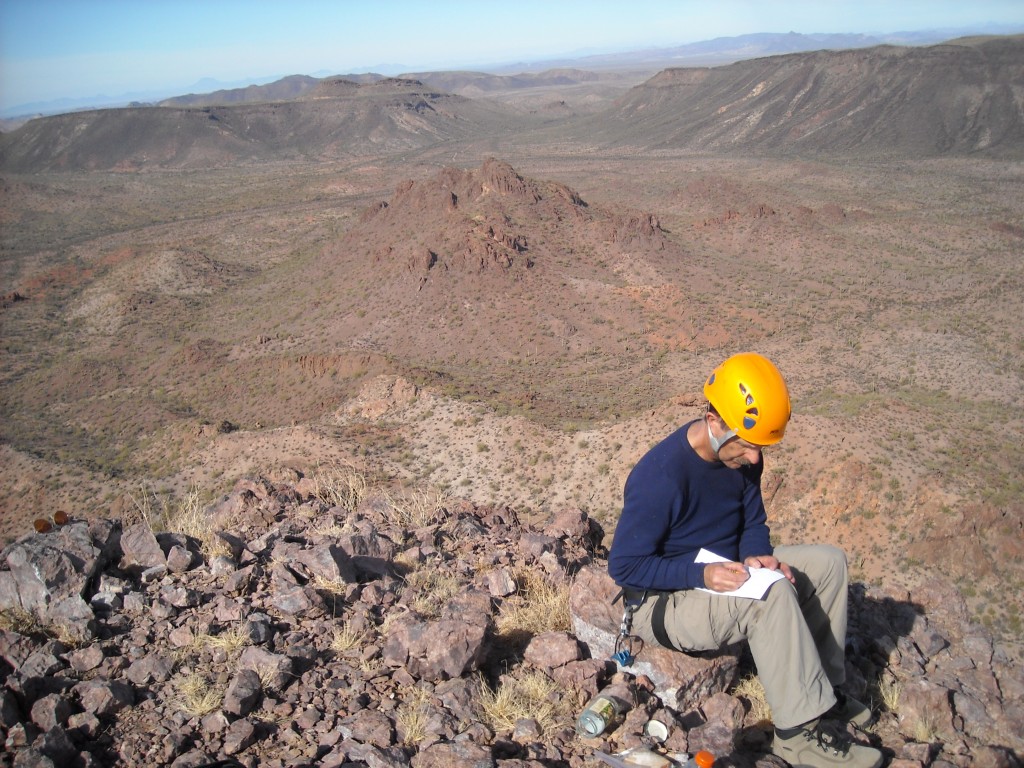

We spent a half-hour on top, ate some lunch, built a nice cairn and left a register. Here I am filling out the register.

Here is the cairn we built.

We congratulated each other and basked in that first-ascent feeling. The view was spectacular – the area is very scenic anyway, and it was as if we were perched atop a high tower looking steeply down on our surroundings. Here is a view to the west over the Sauceda Mountains. Peak 2790 is the double summit in the right foreground.

Here is a view to the northeast, to Donkey Benchmark.

Here’s Andy on the summit.

We finally left and downclimbed to the rope. In this next photo, you can zoom in and see the blue day pack, the orange sling around the rock, and the purple rope. That stuff is sitting right where the difficult climbing ended.

Andy crossed the gap to our anchor. I tied in to the rope and he belayed me across. Just as I started, he said “Stop!” He had seen a boulder perched on the edge of the gap move as I put my weight on it. I very carefully crossed over it and was back with Andy. We set up the rappel, Andy checking all aspects of our anchor around the boulder. Our rappel was straight down the way I had climbed up. I started down and was soon at the slightly overhanging spot. Something didn’t seem right. I looked up and noticed that one side of the doubled rope was caught over a boulder about 20 feet over my head. I hadn’t been paying close enough attention. It was preventing me from descending any farther. My right hand was my brake hand for the rappel, yet it was the right side of the rope which was caught above me. I tried to reach across with my left hand to flip the rope loose from the boulder but I couldn’t do it. I decided to pendulum over to the right to where Andy had set a piece of protection and I clipped myself into it. I extended it a bit so I had some slack, and yet was still anchored safely to the mountain. I thought that maybe I could use the stretch in the rope to my advantage, so I started bobbing up and down (a Yo-Yo moving like a yo-yo!) and after about six bounces it worked, the rope fell down and past me. Much relieved, I continued the rappel and was soon safely down to the base of the climb. Andy followed, cleaning the mountain of the rest of our protection (all of it but one piece, which was too dangerous to retrieve). The webbing can be easily seen from the slope below the south side of Tom Thumb, and it will probably be there forever, until it rots completely away. Here is Andy rappelling down the route I climbed up.

And here’s another look back. Zoom in nice and close. See the yellow line, and the orange line that describes a loop off to the right. Those are our routes. The orange line of Andy’s route doesn’t do justice to the risk he took, pioneering it as he did.

We gathered up all of our gear and left at 4:00 PM. Here’s another view – our route went right up the long groove on the left which is in shadow.

From near the base of the climb, a look to the east over deepening shadows to distant Cimarron Peak on the far horizon..

Once back at the truck, a final glance back to our mountain. Our route went up the vertical right-hand side, then followed the steep slope up and to the left to the summit.

It took us an hour to get back to the truck. After much hard driving, we were back in Tucson by 10:00 PM, eighteen hours in total. What a day! Thanks to Andy for his masterful leading of the climb. He said that it was too dangerous, though, and that he would never repeat it. Coming from Andy, that’s quite a statement.

Please visit our Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690