Day 6 – Sunday, July 31

Today was our last day of actual climbing and we were determined to make the best of it. Clear blue skies greeted us, and after a bit to eat, we were on the move by 6:25 AM. Day packs only, with the 9MM rope for glacier travel, as well as ice axes and crampons. This was back in the day of steel-shank leather boots, wool knickers, knicker socks and Kendal mint cake. For sunscreen, we used clown white, which contained zinc oxide – it was messy but effective. Ah, the low-tech glory days of mountaineering.

Our first peak of the day was climbed by easy Class 3 slabs on its north side. The altimeter said it was 7,030 feet, and we were there by 8:10 AM. After building a cairn, we descended the same north side and continued. The next one was a triple summit – we traversed all three bumps, south to north, and stood on the top at 8:50. The altimeter said this one was 7,120′ and we built another cairn there. The problem with altimeters was that they were notoriously inaccurate – a big change in the weather could create an error of hundreds of feet in the elevation reading. Combine that with lousy topographic maps with a 100-foot contour interval and you ended up doing a lot of guessing.

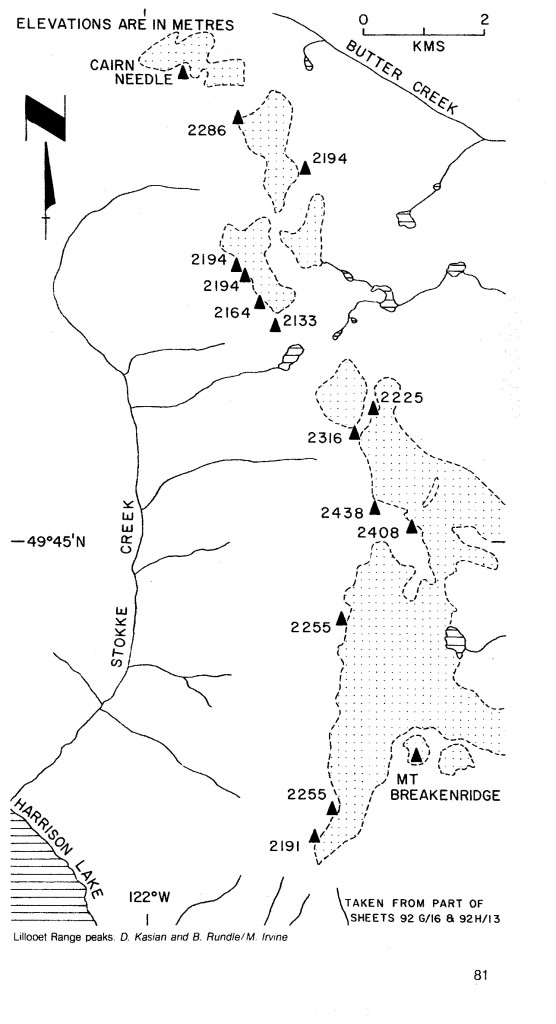

Exiting Peak 7120, we made our way north to a small peak at 7,200′, where we built a cairn, then descended, again to the north, on some very steep snow. Our next objective looked a bit intimidating – we had been eyeballing it for some time. It involved climbing up a Class 3-4 tower on its south ridge, then on to the summit – what an impressive view! We called this one Peak 7,200′, the same height as the last one. Years later, somebody dropped the name “Vista Peak” on it, which is used on Google Earth and the climbing guide for the area. To the north sat Cairn Needle, a peak we knew we wouldn’t reach, but we sat and enjoyed the view any-way. Our first food drop lay only a dozen air miles to the north, but it might as well have been a thousand – we just weren’t gonna get there, not this trip.

There were two more peaks we wanted to climb before the day was through, so we dropped down to the big icefield between the two of them and crossed it. By 12:15, we stood on the first one, Peak 7500, which we climbed by an easy scramble up its south ridge. This was such a beautiful spot, we didn’t want to leave – the best possible place to have some lunch. As with other peaks we climbed on this trip, this was a first ascent but we never thought to name it. Someone in later years decided to call it “Surprise Peak” (we’re not sure why), and it became part of the vernacular, showing up on Google Earth, some websites and in Bruce Fairley’s outstanding book “A Guide to Climbing and Hiking in Southwestern British Columbia”.

After a while on top, we descended to the icefield. Many small birds were feasting on countless insects on the snow-covered glacier, something we saw a lot. Another curious thing were the many butterflies we saw on these summits – not sure why – maybe they preferred the bare ground of the summits to the endless miles of snow and ice. Crossing it to the southeast, we arrived at the top of Peak 7200 at around 2:20 PM. This was to be our last climb of the trip, so we took our sweet time on the summit. There were countless pieces of shale lying around, so, just because we could, we built an outrageous cairn over six feet tall, visible for miles in every direction. In later years, it certainly might have caught someone’s attention, that is if anyone ever went back in to the area. After an hour, we reluctantly left via the south ridge. Once off of it, we found ourselves in an extraordinary glacier-scoured valley – we followed endless slabs of smooth granitic rock, passing fields of heather and small lakes, until we had lost almost 2,000 feet of elevation and ending up in an intensely green valley. There wasn’t a bad moment the whole afternoon. It was a perfect blue-sky day, and it felt like we were in paradise. In over 50 years of climbing, I still look back on this day as one of the finest I’ve ever spent in the mountains, and I think Brian felt the same way. Eventually, we had to head west up a different valley, and at its head crossed over a ridge of grungy rock and moss, then down to camp. Twelve hours had passed, and every minute of it had been sheer climbing bliss. The day had yielded six first ascents, over a distance of 12 miles and 5,050 vertical feet of climbing.

Once back at camp, I too was starting to feel like crap – the “Lillooet-Range flu” had caught up to me as well. Given how badly Brian was feeling, it’s a credit to his stamina how much we were able to do this final day.

Day 7 – Monday, August 1

After a good night’s sleep, we took our time getting up, in fact lazing around until 6:00 AM. By the time we packed up and broke camp, it was already 8 o’clock. It was a bit sad to leave this place, our beautiful lakeside campsite, where we were probably the only people ever to visit. Since our trip had changed radically from its original form, what we needed to do now was to get back out to civilization, and we had a plan. Our camp was sitting above the Stokke Creek drainage, so all we had to do was drop down into it and make our way back to the lake. Sounds simple, right?

Down the steep mountainside we started, and before we knew it were in the midst of some world-class bushwhacking. Long ago, this area had been logged. In the intervening years, there had been some re-growth, and that, combined with the usual trash that loggers leave behind, our descent turned into a real nightmare. Not long before this trip, I had bought an internal-frame pack, quite a novelty at the time, and it served me well as we thrashed our way through the closely-spaced brush. Brian was still using an external-frame pack, and it kept getting caught up on every branch, stem and twig in our path. It was extremely frustrating for him, and here’s how I know. Brian and I have climbed a lot of stuff together in the 38 years I’ve known him, every possible kind of mountain challenge. He’s a pretty cool character, and not much fazes him, But that day, he turned the air blue with oaths – I heard swear words I’d never heard before. In fact, I’d never heard Brian swear before that day, but he made up for it in spades – it was quite a shock, but I can’t blame him one bit. I almost felt guilty as my pack and I slid fairly easily through the brush.

Down and down we went, losing about 3,000 vertical feet on the very steep slope until we finally hit an old spur road. By then, it felt like we’d already had the snot kicked out of us, but the fun was just beginning. Although we now had an old logging road to follow, it was about as much good as having no road at all, it was so overgrown. Even though it was all downhill, it was a frickin’ misery. And hot – it turned out to be the hottest day of the year so far. We literally bushwhacked our way down the old road, swatting the clouds of insects that plagued us. I don’t have any recollection of even stopping for lunch – hell, I don’t know if we even had anything left to eat! Something else that added to the misery was the endless series of deeply-eroded washouts across the road – it had not been maintained forever, and the high rainfall had just eaten it up. It was one long, hot death march down the valley of Stokke Creek. By the time we came to the end of the valley, down at the lake, it had taken us 7 1/2 hours to lose 6,000 vertical feet.

Feeling like a couple of whipped curs, we dropped our packs on to the wooden dock at the lakeshore. God help us, the soul-tormenting thrash that was Stokke Creek was finally over. At this point, I’d like to take a page from Brian’s book – in fact, I am blatantly plagiarizing his description by sharing with you, fair readers, word for word, his excellent description of what happened next. More on where to find this in a bit, but, for now, enjoy.

I dropped my pack, stripped naked and jumped into the lake, man was that refreshing. Mmmm what’s this? All of a sudden there appear three or four teenage girls on the dock. They were very surprised to see us to say the least. Me being naked in the water and all, I was a bit surprised as well. They really didn’t know what to make of us, so they skedaddled out of there to get someone in charge. This gave me the opportunity to get out of the water and dressed. In short order they returned with more girls and two guys. These men were really nervous and concerned about how we got there, who we were, what our intentions were etc. They really didn’t believe that we walked right through their camp over a week ago and again today and no one noticed. It turns out that this is a juvenile detention camp. Only access is by boat or chopper, although there is an abandoned airstrip. The inmates are all here for a thirty day stretch, then it’s back to city detention or release depending upon their situation. These girls pretty much all looked like hard cases; it was kind of sad to some extent. The two guys are councilors-wardens-guards or something like that. Security is solely based on the remote access. There is nowhere to go. The guys were suspicious that we might be trying to break out one or more of the detainees. It was kind of weird. I mean really, look at the state of us. Eventually we were able to assuage their fears, and they realized that we were probably mostly harmless. In fact they went so far as to let us share their dinner with them. The girls had to run a lap of the airfield before getting fed; we were excused this duty. They also let us use their radiophone and we were able to make arrangements for the water taxi to stop by on his next trip, which by luck was tomorrow. Additionally they let us stay in one of the old logging camp bunkhouses; that was pretty far removed from where the girls slept. The bunkhouse was nice in that it kept the voracious mossies’ at bay, but the downside was that there were ants everywhere. A very uncomfortable night and it was hot as hell. I am sure that the guards must have taken turns at watch that night, just to ensure there was no funny business. Which of course there wasn’t.

Day 8 – Tuesday, August 2

They fed us breakfast, and in turn we answered all kinds of questions about climbing in general and specifically what it was like up those old roads. We assured the girls that no matter what they thought of their current situation, that it was like a Club Med luxury resort compared to what they would find if they ventured away from their camp. Before long we heard the unmistakable racket of the boat, and headed down to the dock with our entourage to see us off. I remember there being a family on the boat going for an outing or picnic perhaps. The little boy looked awestruck at the DM and me in all our gnarliness with all of our gear dangling off our packs, I can still see him asking his dad if he can give us a couple of cans of pop from their cooler. A can of cold sprite never tasted so good.

Folks, you can read more of Brian’s engaging and well-written material at his website: www.pangranitichighway.com

Anyway, some final thoughts. As pissed-off as Brian was by his pack during our descent to Stokke Creek, and his vow at the time to never set foot in the mountains again, we were already planning our next adventures before the boat had docked.

In a few days, both of us had recovered from our colds, and, as luck would have it, that part of BC embarked upon a record-breaking spell of flawless weather that lasted over a month. When I think back on our 8-day adventure, one of the most powerful memories I have is that of hunger – we were slowly starving ourselves to death. Each of us started the trip weighing 140 pounds, and I’ll bet when it was over we clocked in somewhere between 125 and 130. And speaking of food – as long as I live, I will never stop wondering about our food drops. Did they burst open on impact? We had some luxury items in them, such as canned fish and nice chocolate, stuff we could gorge on when we got there. Maybe ravens found them and pecked the boxes apart. Not many animals would be up that high on a big icefield, but a bear could be, and if he did, he’d make short work of it. If some such thing happened, we might have arrived and found little of it usable. Then, we’d be in a fix, starving and even farther to go to reach civilization. Oh well, I guess we’ll never know. The Lillooet Range still lives on as one of those great adventures that we all need more of in our lives.

Oh yes, one final thought – this expedition was written up in the Canadian Alpine Journal, Volume 61, 1978, in case you’re interested.

Please visit our Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690