Readers, I feel honored to be able to write about my friend, Barbara Lilley. She has been one of my climbing heroes for many years, and I think it’s long overdue that the world should learn at least some of her story – and what a story it is! I’m going to focus on just a small part of it – her climbs of North America’s five highest peaks.

She was born in Salinas, California on October 14, 1929, and raised in the small town of Gonzales in the Salinas Valley. An only child, her parents were school teachers. During their summers off, she went camping and hiking with them, so she came by her passion honestly. She started working for Langley Corp. in San Diego, and spent five years with them, from 1950 to 1955. The rest of her career in the aerospace industry was spent in Los Angeles, working for Hughes Aircraft from 1956 until her retirement in 1986. Barbara recalls that her first real climb was via a trail to the top of Alta Peak in the Sierra Nevada in July of 1947. In August of the same year, she took the trail to the top of Mt. Lassen. Two years later, she was starting to do cross-country peakbagging in the Sierra Nevada with friends from the Sierra Club. The summer of 1953 saw her in the Tetons, where she climbed Middle Teton, Grand Teton, Nez Perce, Teepe’s Pillar, Mt Owen and Mt. Teewinot.

Barbara spent years peakbagging in the southwestern U.S., but was looking for something more. She made her first big climbing trip outside of the U.S. in August of 1954, to the Selkirk Mountains of British Columbia, Canada. There, she climbed Mt. Revelstoke, Purley Rock, Terminal Peak, Uto Peak, Mt. Sir Donald and Mt. Sifton. She also climbed Mt. Rainier as part of that trip. 1955 saw her return to the same range, climbing Mt. Augustine, Beaver Overlook, Mt. Selwin, Wheeler Peak, Kilpatrick Peak and Grand Mountain.

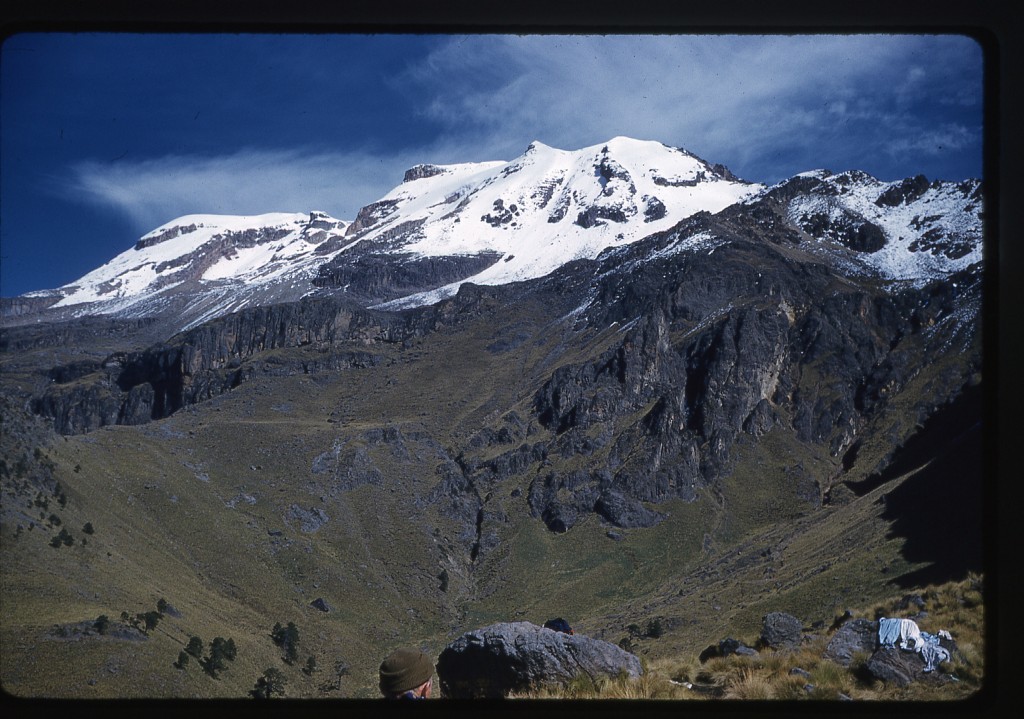

The first one of North America’s five highest peaks that Barbara tackled was Pico de Orizaba, or Citlaltépetl. Mexico’s tallest, at that time it was thought to have an elevation of 18,855 feet, but is now more correctly considered to be 18,491 feet. She rode down to Mexico with a group of UCLA students who belonged to a club called the Bruin Mountaineers. At the El Paso border crossing, there was the usual backup, but when the Mexican customs agents saw their ice axes, they said “Ay, alpinistas!” and waved them on through. She said that rather than getting acclimatized on Popo first, they went straight for Orizaba, and she failed on that first attempt. Fortunately, there were enough interested climbers to make another attempt a week later, and she was successful that time. Things were really different for climbers attempting the big Mexican volcanoes so long ago. Many of their concerns were different than those of climbers today. Let me share some of them with you.

They felt that everyone in the party should be immunized against typhoid, paratyphoid and tetanus, and should carry a certificate of vaccination. They tried to minimize the distance driven in Mexico by entering at the Laredo border crossing – that way, they could avoid the much longer run in Mexico that would result from crossing at Nogales, thus avoiding sudden poor stretches of unpaved roads, many detours, potholes and innumerable animals and humans on and along the roads. They felt that because the danger of colliding with a large animal was very real, they should only drive during daylight hours. They believed that it was not safe to eat and drink at will throughout Mexico, so they brought with them a lot of water, canned foods and liquids. Even so, some still suffered from intestinal upset. Only after their climbing was done were they willing to eat in Mexican restaurants. Some of them took Enterex tablets as a precaution. Respiratory ailments prevented some from summiting and made the ascents in general more difficult. A new potent antibiotic called Ilosone was available at the time and used by their party for more severe respiratory problems. They carried Halazone tablets to purify water as needed, but felt that water obtained at high altitudes was safe to drink.

On December 17, 1955, her group left California and made their way, via El Paso, down to Ciudad Cerdán in the state of Puebla. There were 6 in her party. Upon arriving, they contacted Cristoforo Jiménez, a local packer and climbing guide. He charged 20 pesos per man and/or mule per day, so their tab came to 420 pesos for the expected three-days use of his services. At this time, one Mexican peso was worth 8 cents U.S. In hindsight, they felt they could have gotten by with two days instead of three. They parked their cars in the courtyard of the Hotel Faustus, and for an additional 5 pesos per day got the hotel owner to protect them.

On Christmas morning, under clear skies, their five animals (three burros and two small horses) and two packers filed out of town with the climbing party.

They traveled 12 pleasurable miles and climbed 6,000 vertical feet to a cave, the Cueva de los Muertos. Once there, they felt that they could have found the cave without guides, but since they and the mules were inexpensive (and since they wanted to conserve their strength for the summit climb), they felt it was wise to hire animals and a packer. The cost for an expected three days was $3.36 per person.

They began the climb early in the morning of December 26.

From the cave, a trail dropped 50 feet down into a wide valley. They then proceeded up the valley for a mile or so, veering to the right and reaching a ridge, which they more or less followed on its eastern slope. Their route then veered to the left as they climbed.

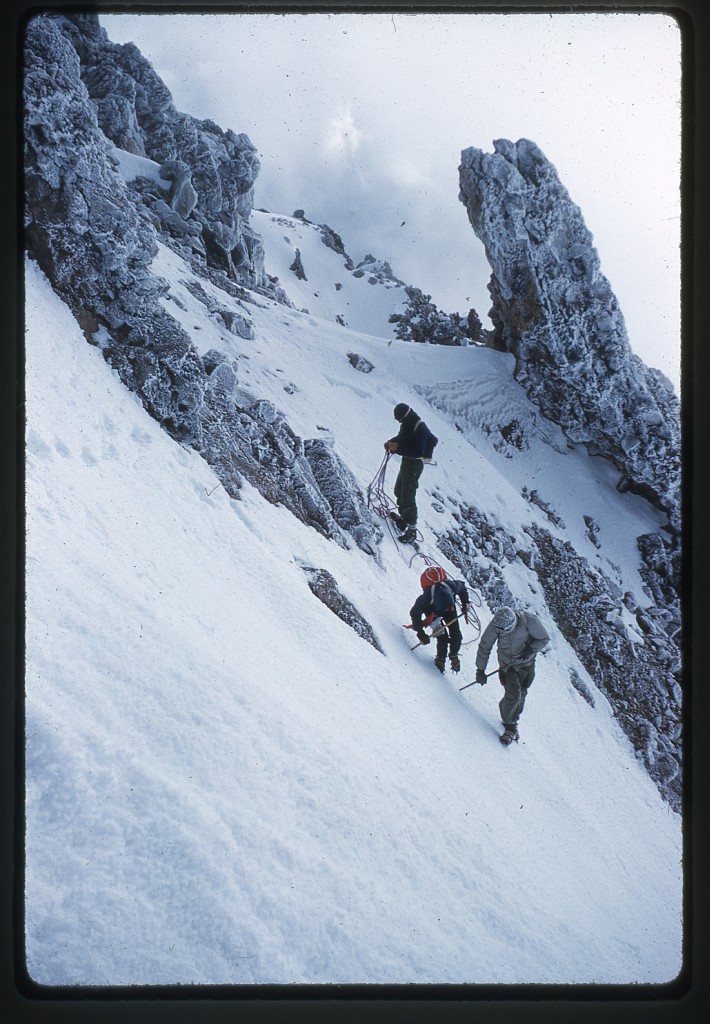

Up above, they could see a lower and an upper band of rocks. They followed a snow gully straight up between the two rock bands.

Above that, looking towards the summit, they could see two prominent rocky areas – they made their way up between the two, staying closer to the left. The actual summit was only 30 feet higher and 100 yards beyond the rock.

The climb from the cave to the summit had taken 6 1/2 hours. The snow was so icy that they couldn’t glissade on the descent. One of their team was having a problem, so they ended up spending another night in the cave. They walked back out to Ciudad Cerdán the next day, and stayed at the hotel that night. Their drive back to California must have felt pretty good, relishing their successful ascent of North America’s third-highest peak. They made it back home on New Year’s Day of 1956.

That summer, Barbara and a group of friends headed north again to British Columbia, this time to the Vowell Creek area. During a week spent there, they completed three first ascents. The first was Pk. 9400+, to the northeast of Bugaboo Spire. Next came Peak 9250+, 1 1/2 miles northwest of Hauser Spire. The third was a peak known as “Last Chance” which was 9,600′. She wasn’t done yet. The same summer delivered up another big trip, back in Wyoming, with ascents of Gannett Peak, Mt. Woodrow Wilson, Fremont Peak, Mt. Helen, Mt. Warren, Doublet Peak, Sphinx Peak, Rampart Peak, Bastion Peak, Mt. Moran and Symmetry Spire. A side trip to bag Mt. Shuksan finished off the summer in style.

The summer of 1957 saw Barbara setting her sights on even bigger game. She went up to the St. Elias Mountains in the Yukon Territory and, with her friends, did some great things – six first ascents in their two weeks there, as follows: South Gemini (12,000’+); Snowfield Peak (13,300’+); Strickland Peak (13,800’+); Mt. Soloman (11,500’+); Peak 10,000’+; another Peak 10,000’+.

The following year, the month of August was a busy and productive one for Barbara’s peakbagging career. She made it to the summit of Mt. Jefferson, Mt. Hood, Mt. Washington, North Sister, Middle Sister, South Sister, Glacier Peak, Mt. Baker, Mt. St. Helens, Mt. Adams and Mt. Olympus. There was no stopping her, this girl was on fire!

Late in the same year, Barbara returned to Mexico, this time to attempt the other two big volcanoes. It was December 19, 1958 when her party of 11 climbers left California. This time, they entered Mexico at the Laredo, Texas border crossing. After the long drive down to Mexico City, they headed over to Amecameca, the town nearest to Popocatépetl, North America’s fifth-highest peak. At that time, the 26-KM. road up to the Paso de Cortés was dirt, not paved as in later years.

Another 3 KM brought them to the road’s end at a climber’s hut. I’m not sure how big the hut was, or how many it could accommodate. In later years, the much bigger Tlamacas Hut was built. Anyway, I digress. Their hut was described as “a brick and glass building that is maintained by one or two men during the entire year.” A tip of 5 to 10 pesos was recommended to stay there, but not required. Climbers slept on the floor, and a fire was kept in a large fireplace. Electric lighting was provided, and safe, palatable water could be pumped from a well.

All 11 members of the party started out at 4:30 AM on December 24th, after sleeping in the hut at 13,000 feet. The previous day, to get in shape, several of their party had climbed up to what was called the Orange Hut at around 14,000 feet. Today, they were getting an early start because clouds started forming around 1:00 PM each day. They witnessed a beautiful sunrise, and saw Orizaba starkly outlined 80 miles away to the east. They reached hard snow at 14,000 feet and put on crampons.

A tent was situated at a spot called Las Cruces at 14,600 feet, and from there it was a straight shot up to the lower edge of the crater rim. This next photo shows them skirting the rim of the huge crater.

There was another tent at that spot, about 17,000 feet. A lesser summit was over to the left, but the true summit was obvious and off to the right.

When they reached the top, another 800 feet higher, there was another tent, but no register.

When Barbara’s party made their ascent, Popo was thought to have an elevation of 17,888 feet. Lists of North America’s highest peaks do not seem to agree, but a realistic elevation seems to be 17,749 feet.

Their group had made good time, about 7 hours to the summit. Few were hungry, and surprisingly, few were thirsty. Only one of their party felt nauseous, but several felt some dizziness on the climb. It hadn’t been too cold – they felt that a down jacket wasn’t necessary, that a couple of sweaters and a parka were adequate. Sunglasses were a must, though, as well as a good glacier cream, gloves and ice ax. On the descent, they “pants glissaded” from the rim tent for more than 3,000 feet.

After descending Popo on December 24th, they spent Christmas Eve in the big hut. The next morning, they drove back down to Cortez Pass, then drove on to Las Minas.

Their thinking was that, since they were already in the area and now acclimatized from their Popo climb, why not go for Iztaccihuatl right next door. At the time, it was thought to have an elevation of 17,343 feet, making it the 7th-highest peak in North America. There was a small hut by the parking area which could sleep eight people, but it had no water. Of the three big Mexican volcanoes, even though this was the lowest, it had a reputation of being the longest and most strenuous climb, the one with the trickiest route-finding. The name “Iztaccíhuatl” is Nahuatl for “White woman”, reflecting the four individual snow-capped peaks which depict the head, chest, knees and feet of a sleeping female when seen from east or west.

Once at the parking spot, their group split up to explore various routes they might use to reach the summit. While they were out doing that, a Sierra Clubber from San Jose, California came along with a Mexican guide, one Mario Gomez of Mexico City – they were on their way to spend the night in the hut at the knees. The group was excited, because they felt they could follow in their footsteps the next day.

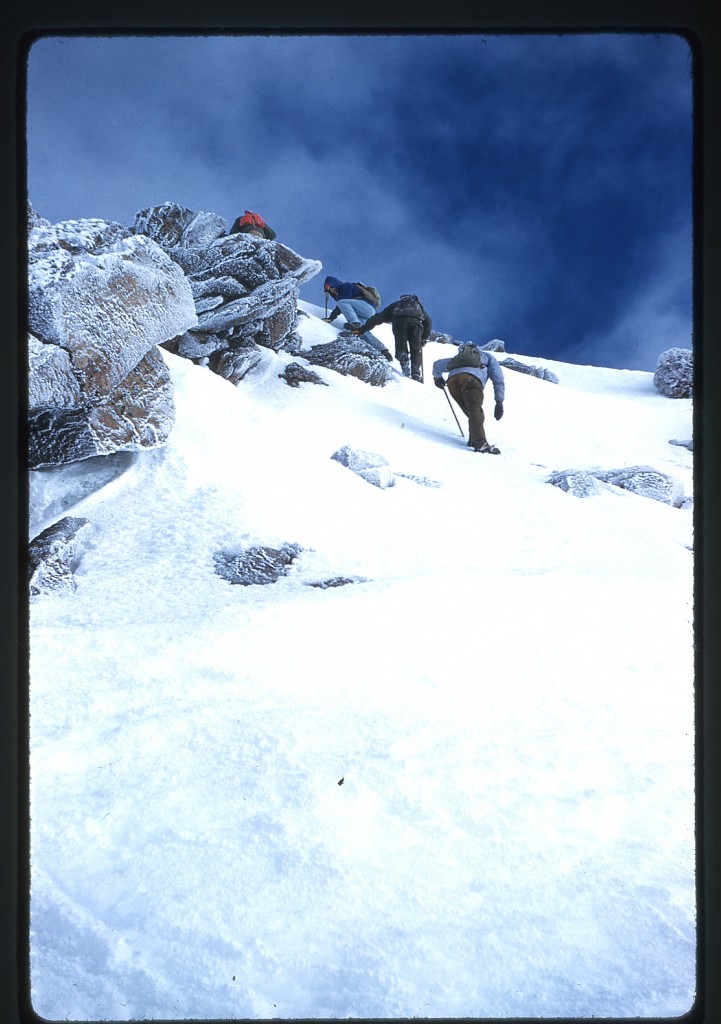

However, during the night a storm moved in and rain fell. When the group got up at 2:00 AM, clouds were everywhere and the ceiling was just above the hut. Since they knew where the trail was, they started out at 3:00 AM, hoping that the weather would clear. When they arrived at the saddle before the knees, they were in the clouds, and it was cold and windy. Since the trail had petered out, they didn’t know which way to proceed. Thanks to the stamina of Jon Shinno, one of their party, they forged ahead and found the hut. Mario and his San Jose client were still in their sleeping bags. Amazingly, 12 of them crowded into the small hut (one of their party had turned back). They waited 30 minutes, and managed to convince Mario to guide them through the swirling clouds.

They plodded on with crampons, and the weather finally broke to reveal blue skies.

At one point, two of them and the guide climbed up rocks while the others cramponed up 25 feet of steep snow. Either way, there was plenty of exposure. From that point on, it was a long walk to the summit, which is not readily distinguishable since it is an undulating plateau.

Fortunately, the guide knew the exact summit and they stomped all over the chest, anatomically the highest point of the sleeping lady. It had taken them eight hours of climbing, and they won their hard-earned summit.

They were able to do a 500-foot glissade on the way back to the hut.

Their round-trip distance for the climb was about nine miles. On December 28th, Barbara flew from Mexico City back to Los Angeles.

She had now climbed the three big Mexican volcanoes, which happened to be the 3rd-, 5th- and 7th-highest peaks in North America. What was next?

Please stay tuned for the exciting conclusion of this story, where we see Barbara go after difficult northern peaks in the Yukon and Alaska.