When we last met Barbara, the year 1958 was winding down, with successful ascents of Popocatepetl and Iztaccihuatl, plus a prior ascent of Citlaltépetl, she was back home in California feeling pretty darn good about her successes south of the border. A few short years later, she was setting her sights on the continent’s very highest peaks. These Arctic giants posed a different set of challenges than those of the Mexican volcanoes – let’s see how she went about meeting them.

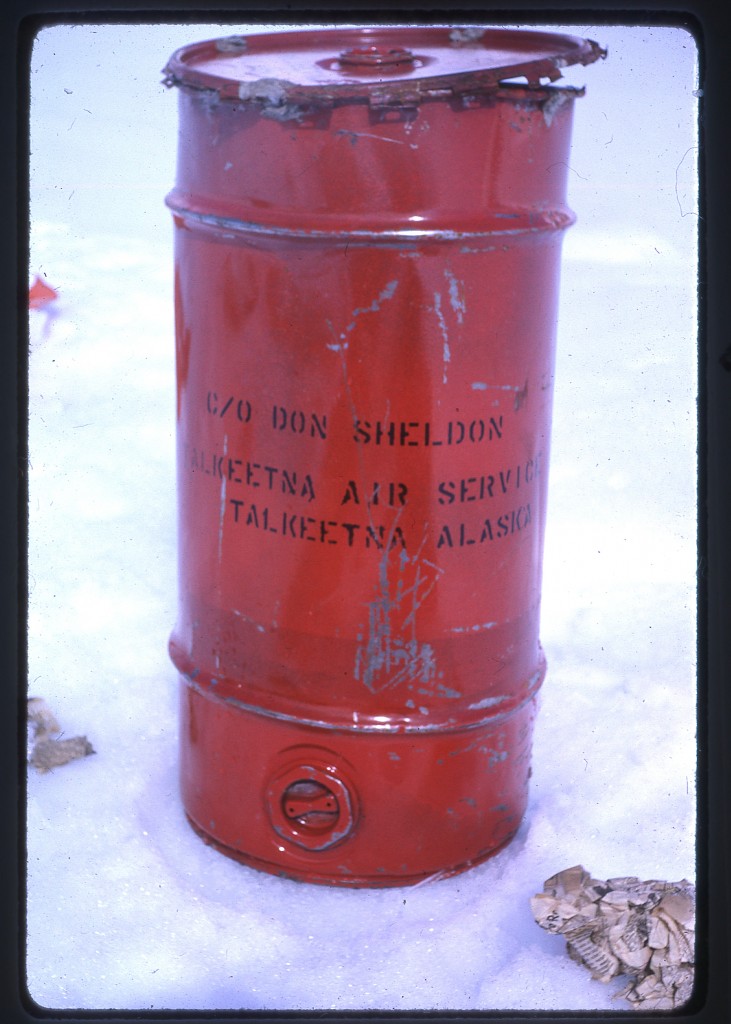

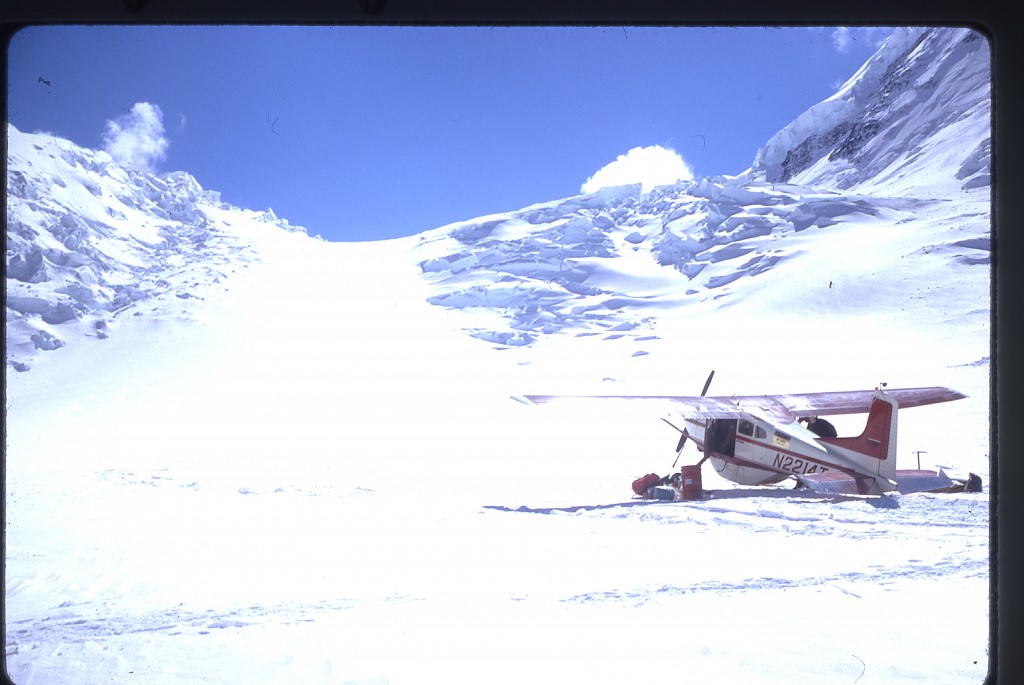

The first one she went after was Mt. McKinley (called Denali by many), the continent’s highest. Its long-accepted height was 20,320 feet, but recent surveys have lowered that to 20,237 feet – no matter, it’s still our highest. After driving to Seattle on June 26th, 1964, they flew to Anchorage the following day. There, they were met and checked out by the Alaska Rescue Group (a standby rescue group in Anchorage was required at the time; fortunately, Barbara had previously climbed with one of its members). They spent the night in Anchorage, then boarded the Alaska Railway and rode to Talkeetna on Sunday morning. They spent the next three days waiting out the rain in bush-pilot Don Sheldon’s hangar – thankfully, there were three bars and an ice-cream stand to help pass the time. Finally, all six of their party were flown in to a 7,000-foot landing site on the Kahiltna Glacier just outside the park boundary.

That done, their next task was to snowshoe to their 8,000-foot air-drop site six miles away, which they did that evening (one airdrop was allowed at that time).

They had time on their side, as it never gets completely dark at that time of the year. At their drop site, luck was on their side – they recovered intact everything but some of their fuel.

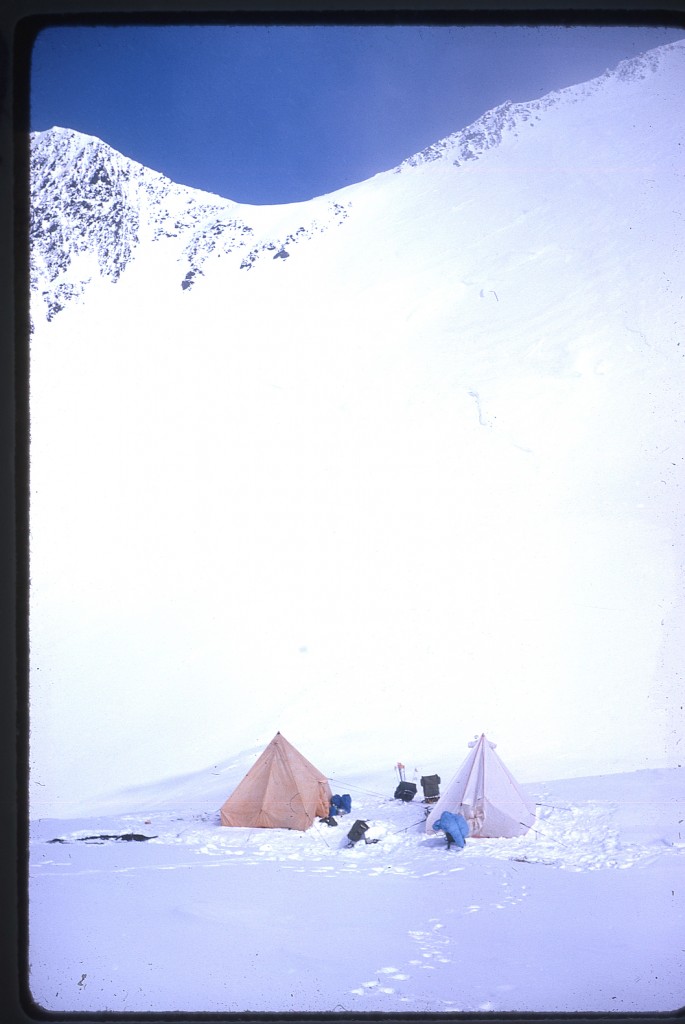

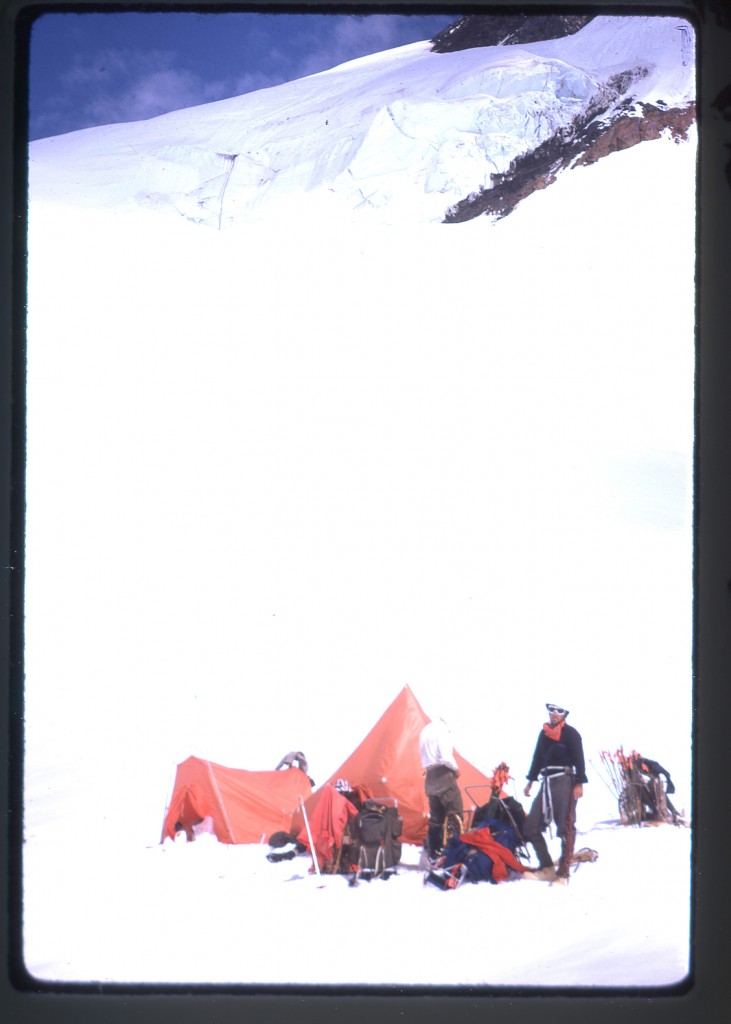

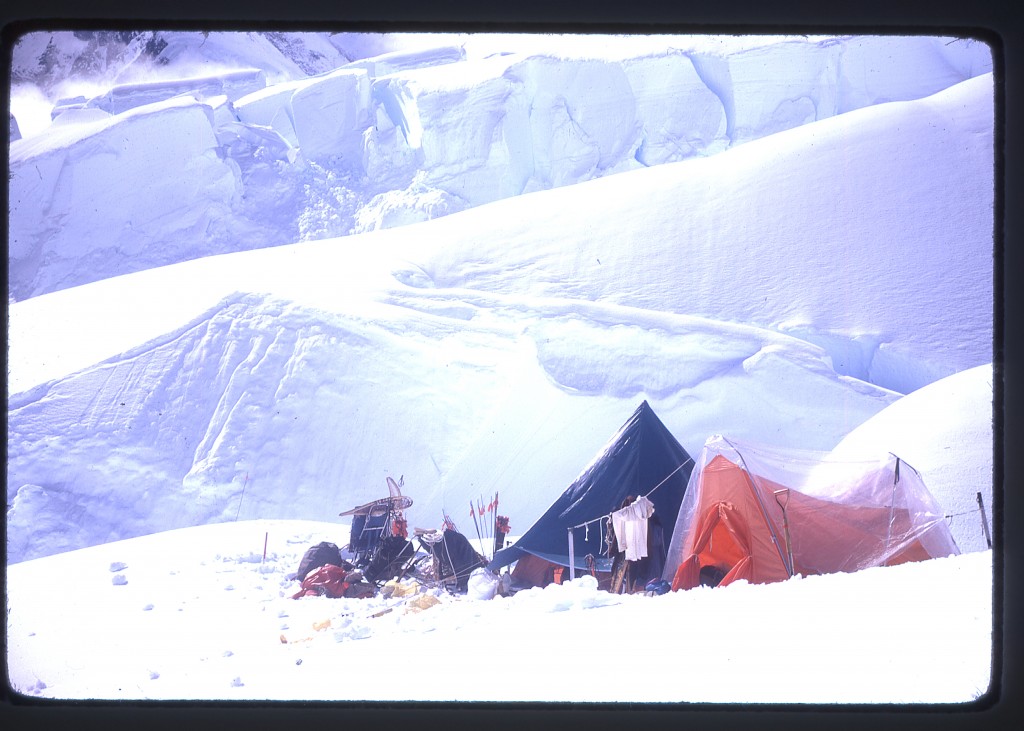

The team set up their first camp at the site of the airdrop.

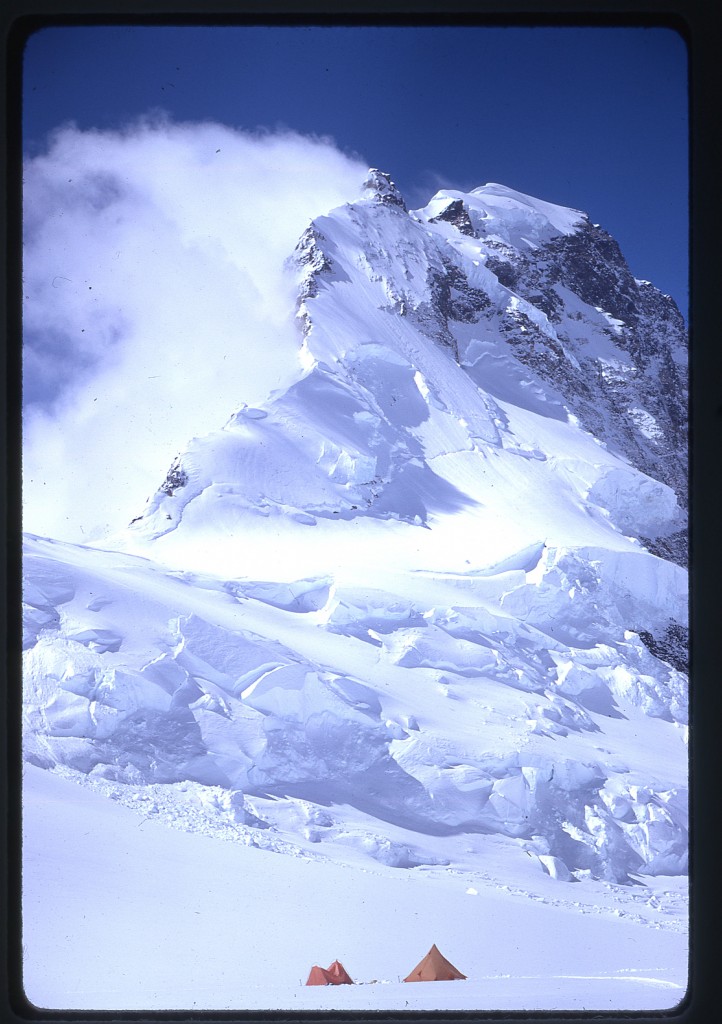

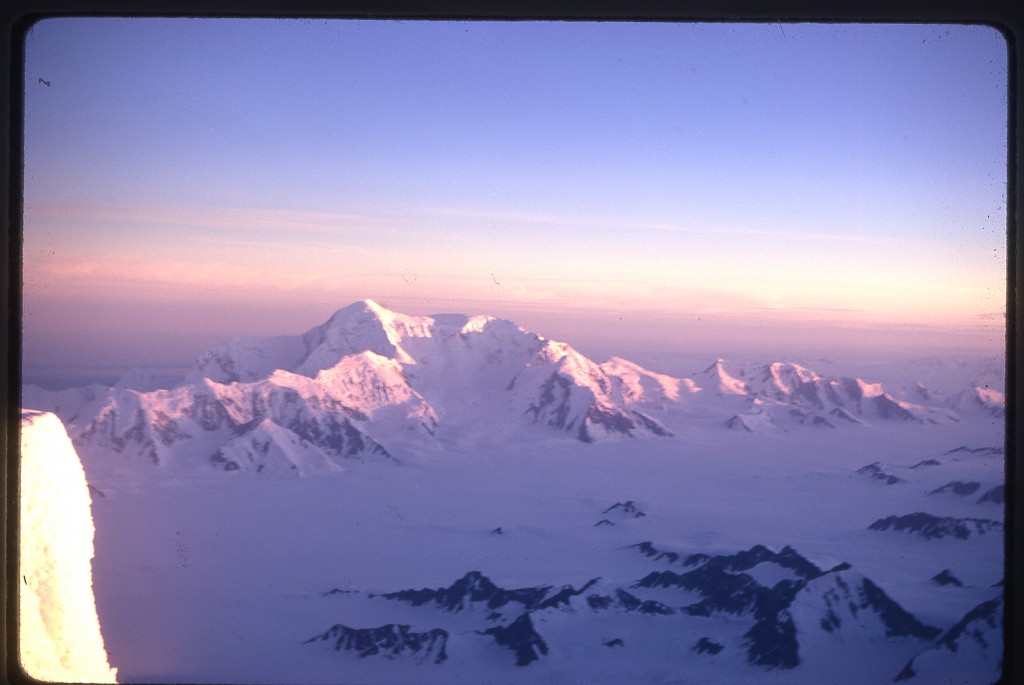

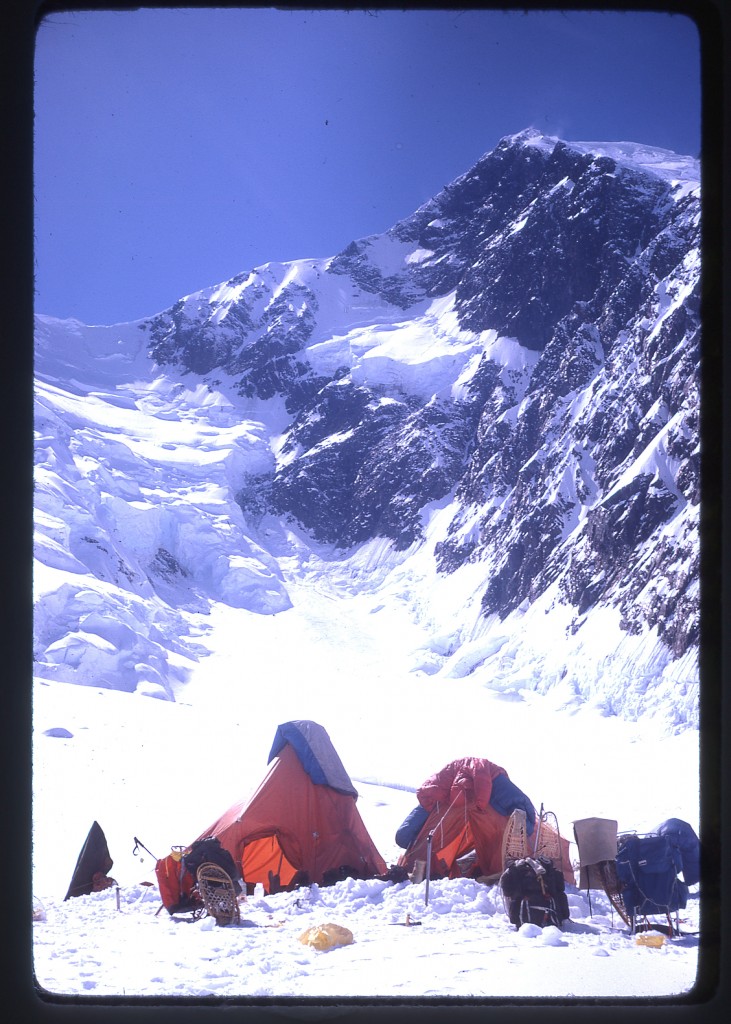

Here is the view of McKinley they had from near their first camp.

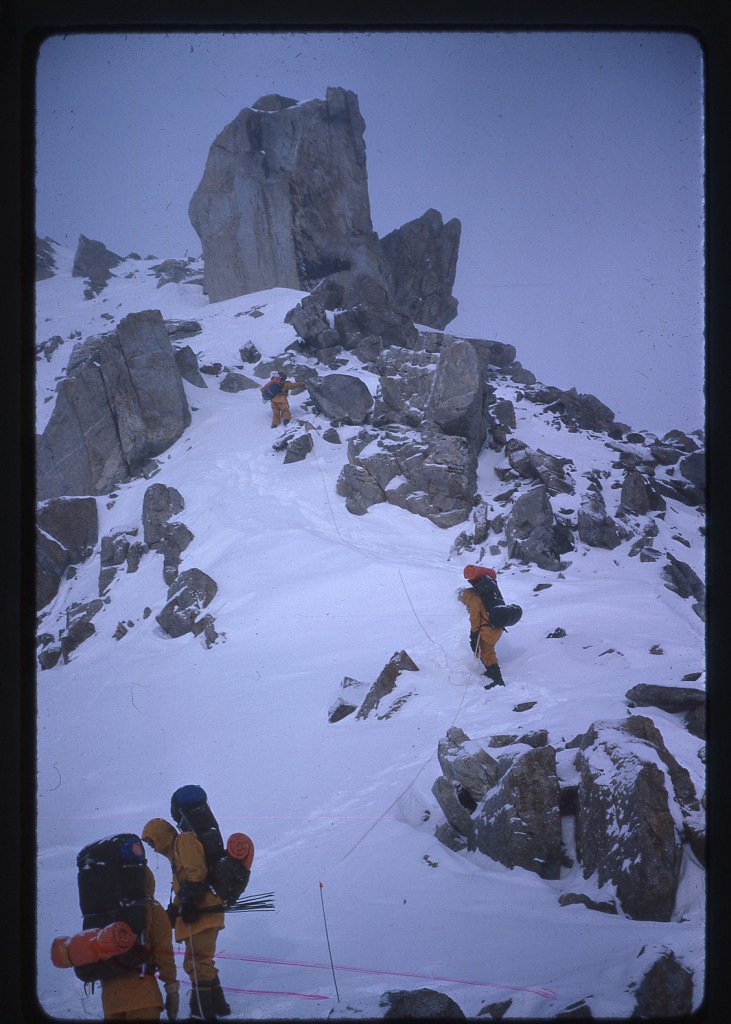

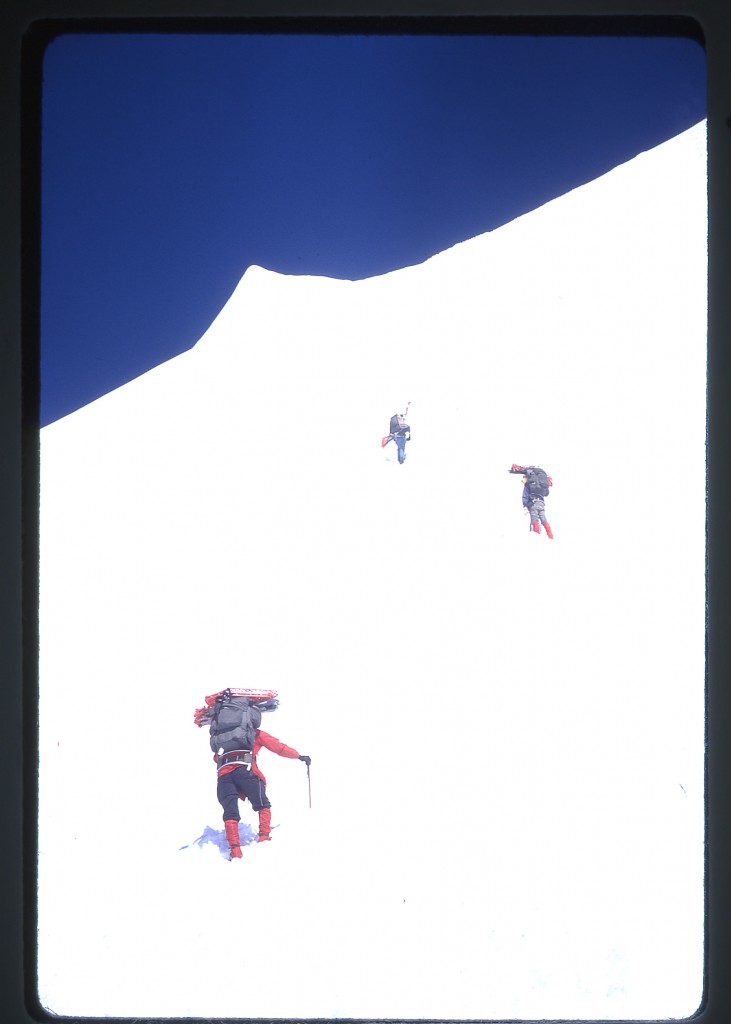

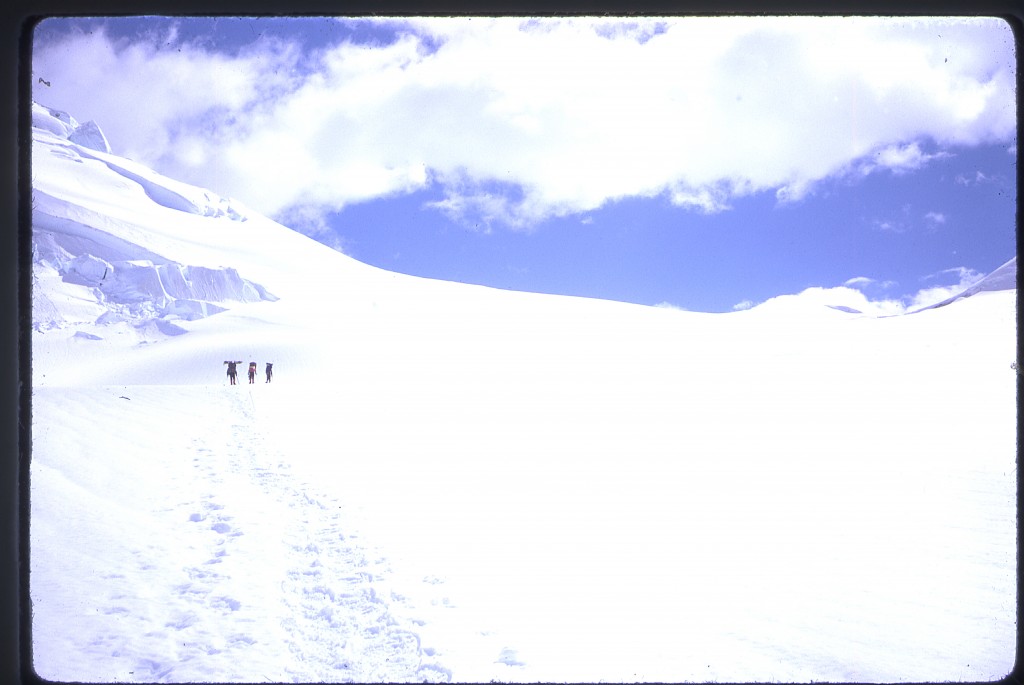

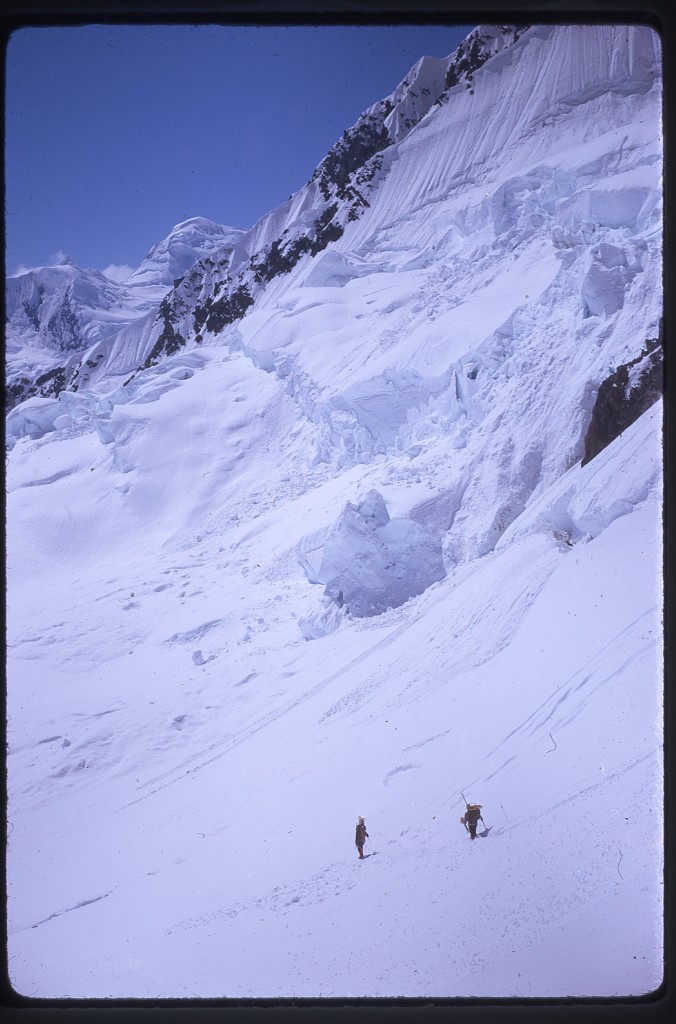

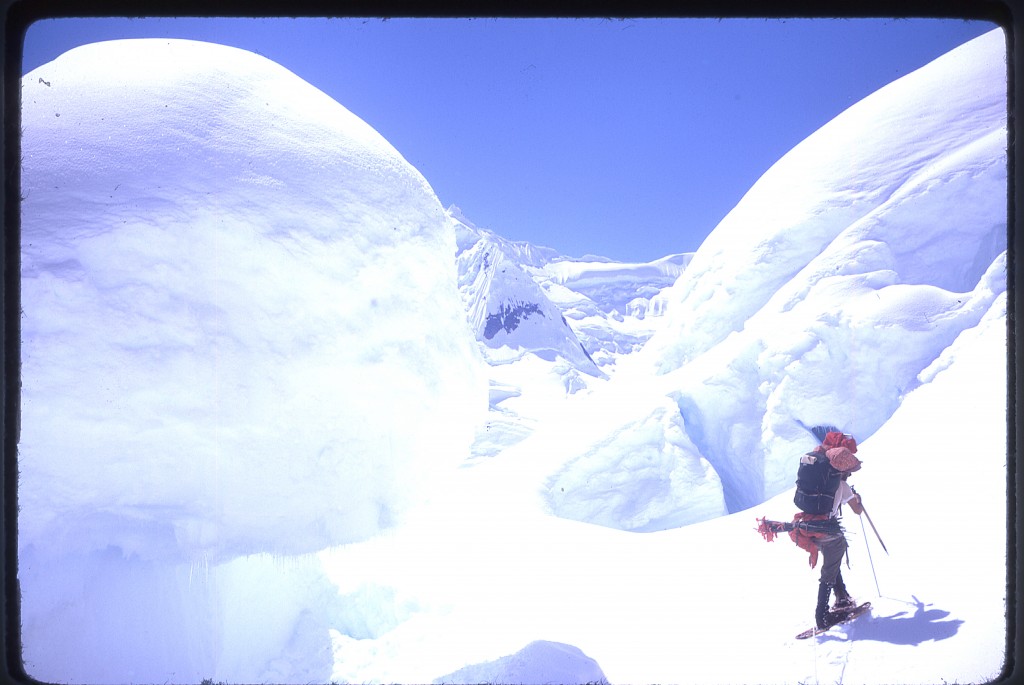

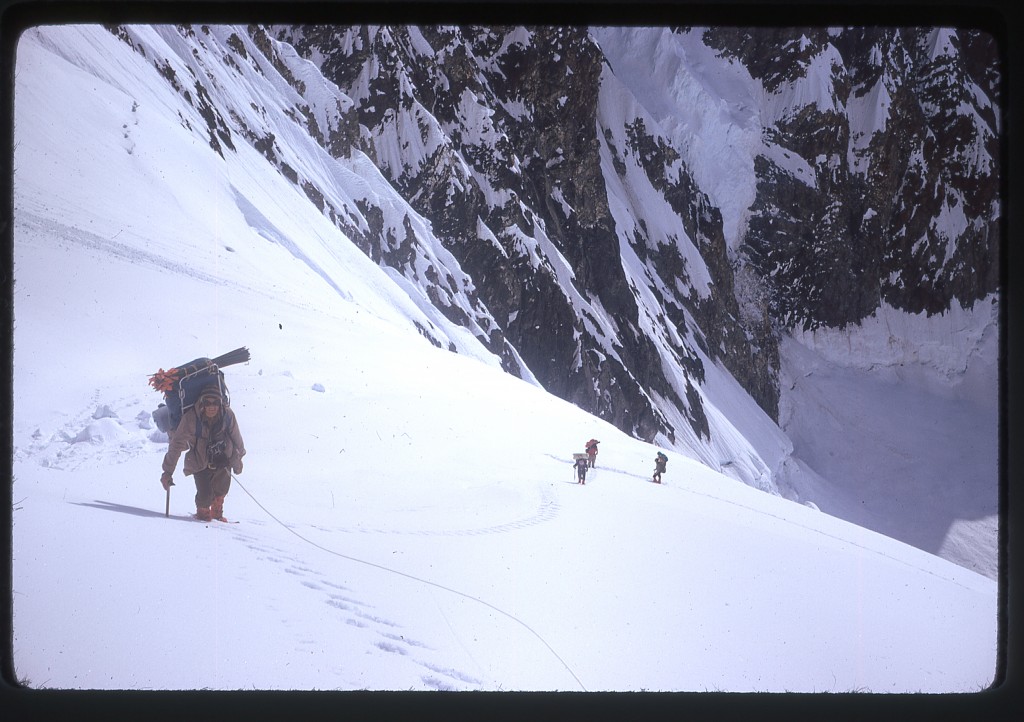

Here’s a view of a part of the route on the way to Camp One.

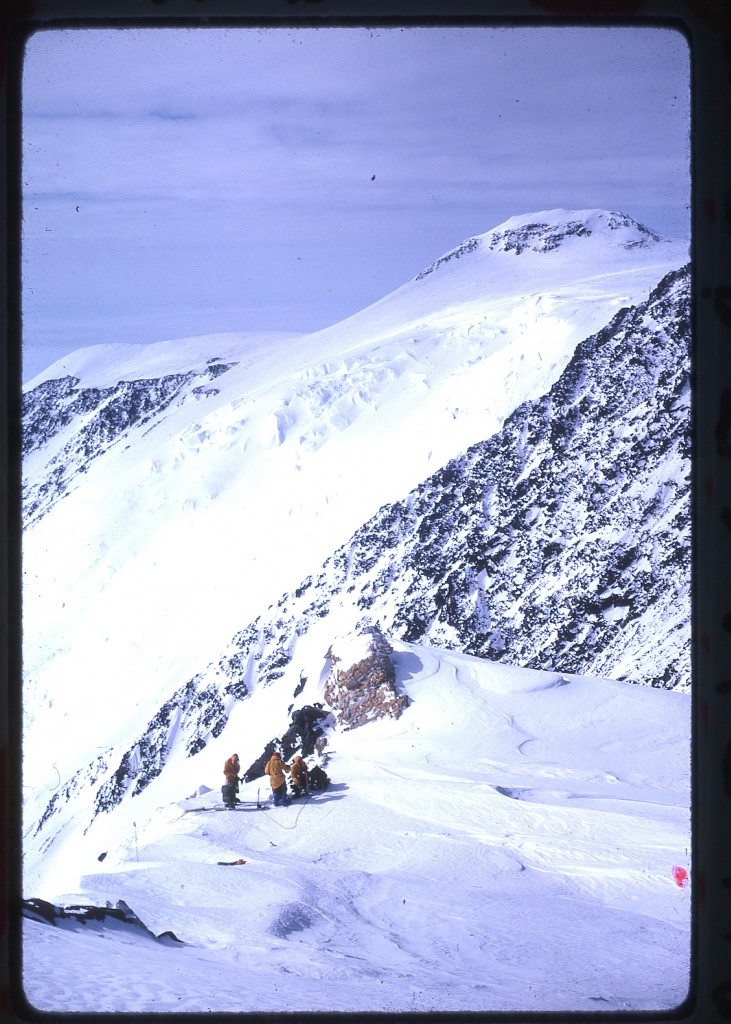

The next two days, July 2nd and 3rd, were spent relaying food and equipment, through alternating oppressive heat and blinding snowstorms, to Camp One at 11,000 feet.They spent two more days, in similar conditions, bringing their camp up to 14,200 feet, below the steep wall of the West Buttress.

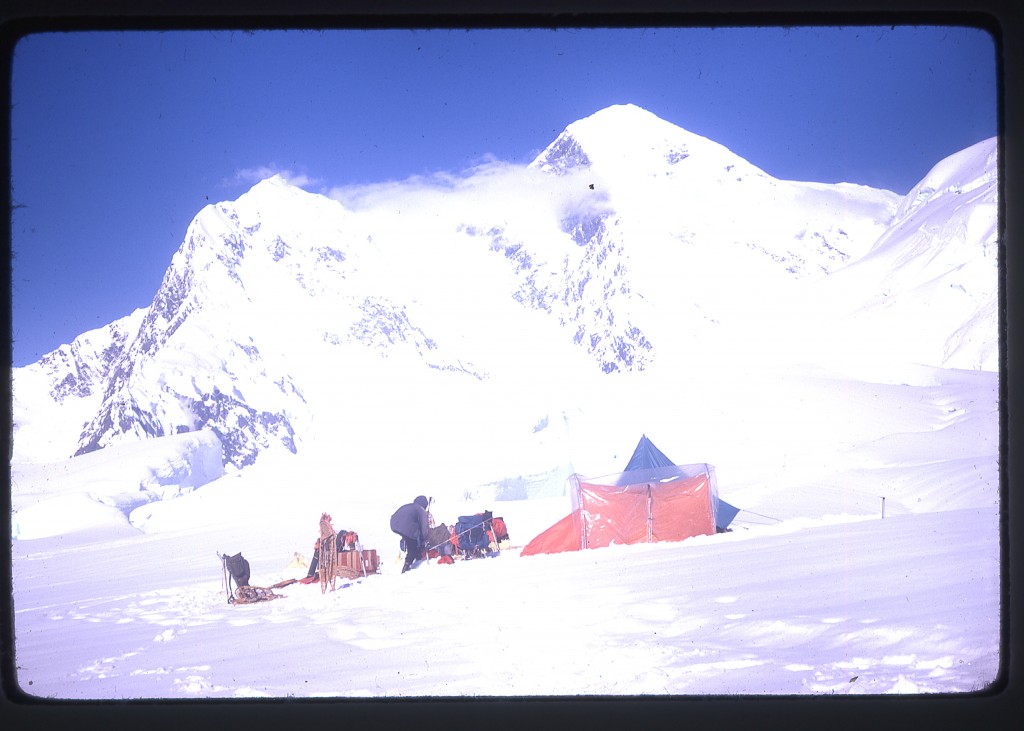

Approaching Camp Two with Foraker in the background. The dark line across the upper left is a flaw in the photo.

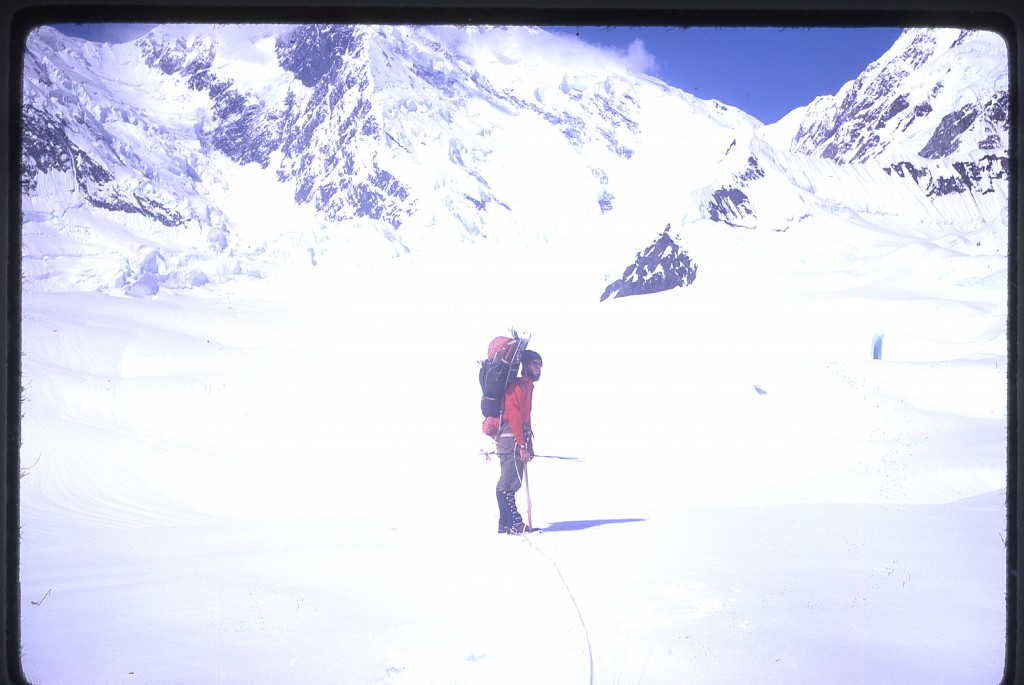

Three more days were spent relaying food to a cache at the top of the the wall.

Finally, at 15,200 feet, they cached their snowshoes in a snow cave – only crampons would suffice from that point on.

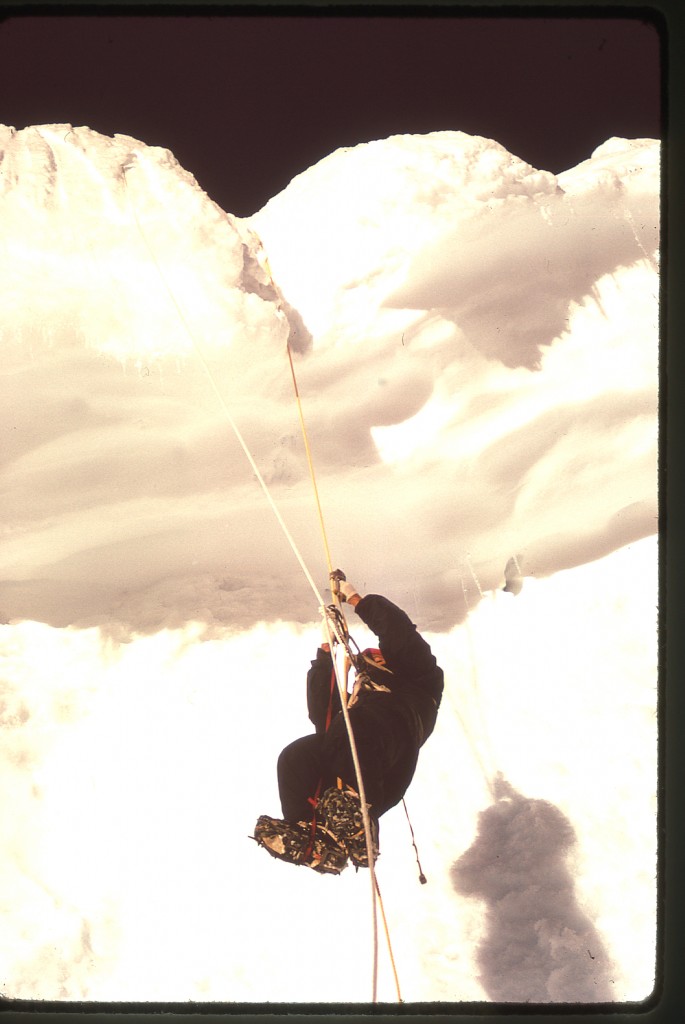

There were fixed ropes in place on the wall, which were used on its descent, but not on the ascent – for that, good steps were made. Those were the good old days!

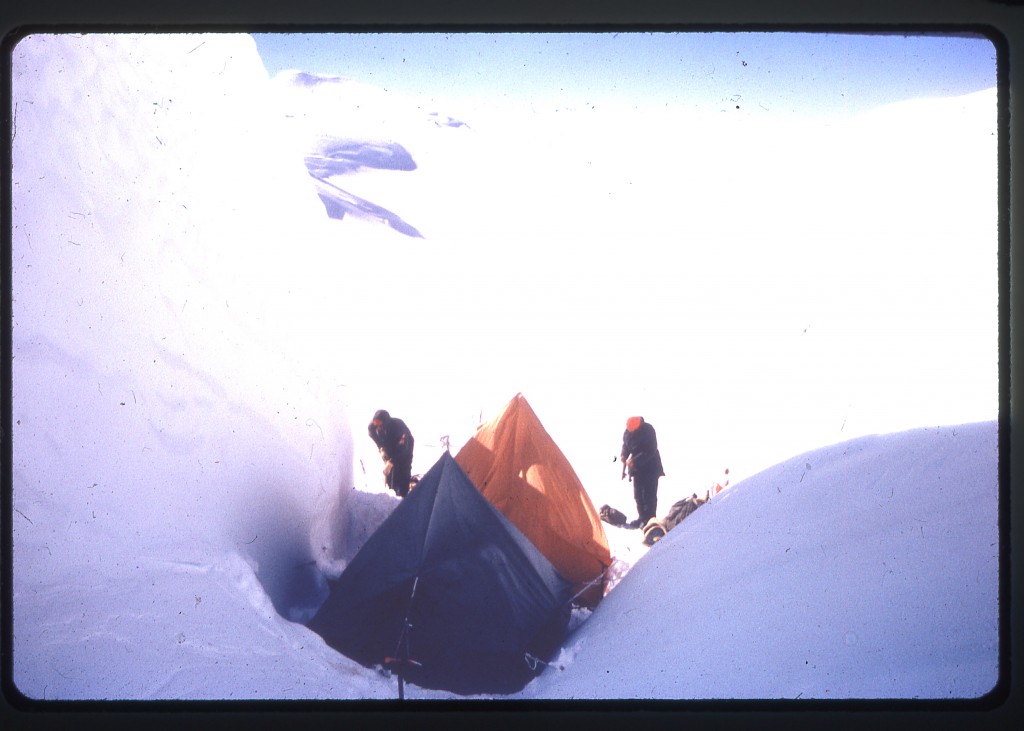

On July 8th, they moved their camp up the steep wall and along the top of the buttress to a snowslope below Denali Pass, at 17,200 feet.

There, they were pinned down by storms for three days. To be on the safe side, they dug a snow cave in case their tents were destroyed by winds, but thankfully didn’t need it. On July 12, they made the final climb. The party required four hours to reach the ridge above Denali Pass, due to soft snow.

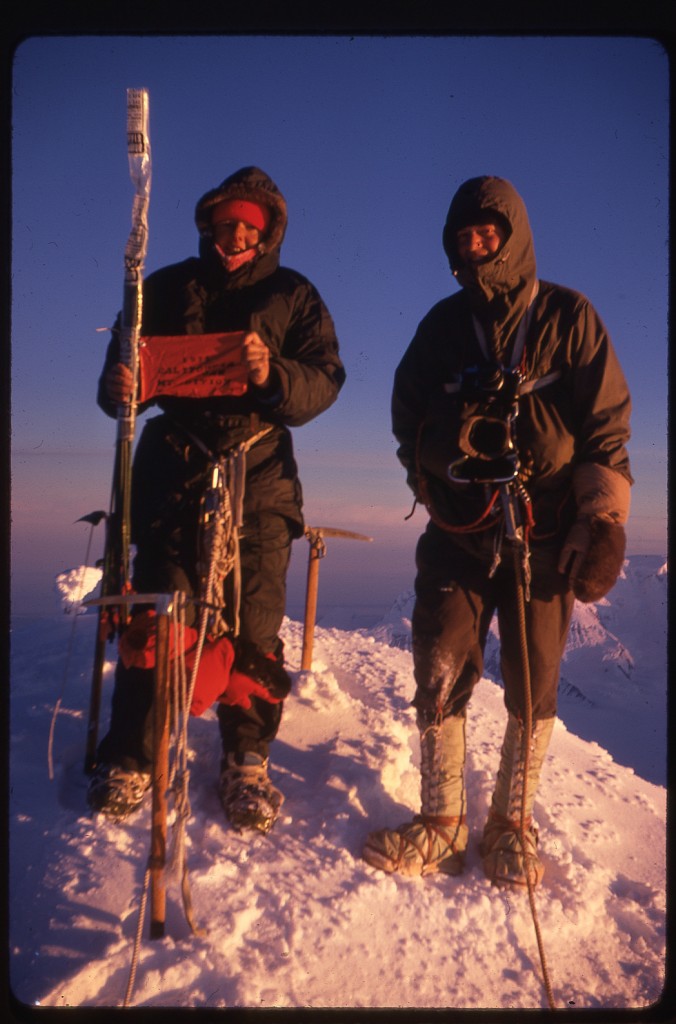

Four hours after that, they were on the summit – they had followed the trail of a large party of 15 that had climbed from the north a few days earlier.

While on the summit, clouds covered everything below 14,000′. The temperature was around zero, but the insulated overboots the party was using prevented any frozen toes.

They descended back to their camp at 17,200′ in only three hours. During the next two days, the weather worked in their favor. They recovered their snowshoes and retraced their steps through three feet of new snow, past their airdrop and on to their pickup point. They were picked up by Sheldon on the morning of the 3rd day, and reached Anchorage in time to catch the flight to Seattle that evening. The long drive to Los Angeles was all that remained to be done.

Once back home, after minor repairs to the snowshoes, they were returned to their friends from whom they had borrowed them. They called their trip the “Southern California McKinley Expedition”, and you certainly can’t take that away from them. Things were much stricter back then, and it was a lot tougher to get permission to climb the mountain. McKinley saw its first ascent in 1913, but the second had to wait until 1932 and the third until 1942. Park records show that 37 climbers tried for the summit the year of Barbara’s climb, and 25 of them made it. From 1903 to 2014, a total of 40,884 climbers attempted the peak, and 21,278 successfully summitted, (52%). In 2014 alone, a total of 1,204 attempted the climb, and 429 of them stood on the summit.

Barbara next set her sights on Mt. Logan, Canada’s highest peak. Back in 1971, the year of her attempt, Logan was believed to have an elevation of 19,850 feet – it has since been revised to 19,551 feet. Although it is 686 feet lower than McKinley, all comparisons between the two end right there. I mean no disrespect to those who have sacrificed much and worked so hard to climb McKinley, but Logan and McKinley are not in the same camp. For every climber who summits Logan, 13 do so on McKinley. It’s not just because McKinley is a bigger draw due to its height, it’s because Logan is far more difficult. Mt. Logan is so big, it is said that the sheer bulk of the mountain (its volume in cubic miles) that sits above the surrounding land is greater than any other mountain on earth, anywhere, period. Here’s another mind-blowing factoid about Logan – take a guess – how far is it around the mountain if you trace a line along the 14,000-foot contour, along every little detail of the topographic map at that level? You’re probably not going to guess correctly. What do you think? – 20 miles? 30 miles? 50 miles? Nope. Try 90 miles. Yes, 90. NINETY MILES!!!! And, folks, there’s a whole lot of Logan above that 14,000-foot contour. About 58% of the climbers who have ever attempted Logan have made it to the summit. So here’s what happened with Barbara’s attempt on the mountain.

She and five climber friends met at the Fairbanks airport on June 19th, and were driven to Glenallen, Alaska where their glacier pilot was based. There, due to bad weather, the waiting began – six days later, they were flown to an intermediate landing strip at May Creek. A day later, two of the party were flown to the 11,000-foot level in the King Trench on Mt. Logan.

However, after that flight, the plane developed landing-gear problems. That caused enough delay that a major storm moved in and the others, including Barbara, were unable to join those two for nine more days, until July 5th. Meanwhile, one of her team had left to return to his job. Another expedition from Oregon was landed later that night, whose goal was to climb both Logan and Mt. St. Elias.

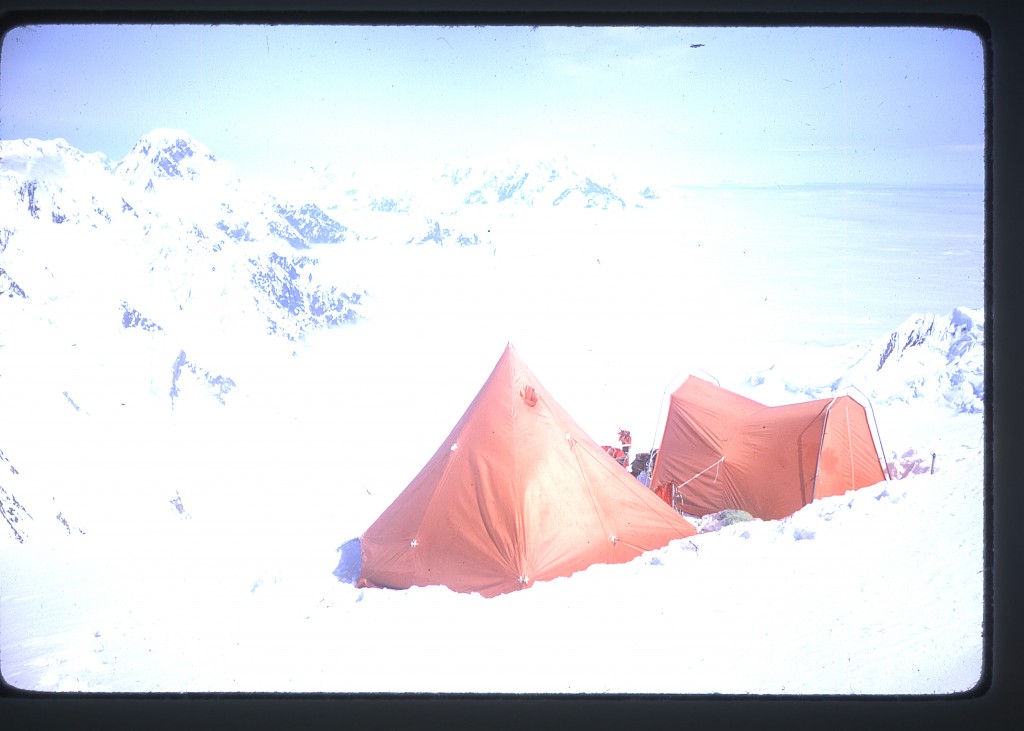

The next few days, the weather was generally good, and the five climbers, alternately relaying supplies and moving their camp, established Camp I at King Col, at 13,500′ on July 6th.

On July 8th, after climbing a steep face above the col where a fixed rope was used, they established Camp II at 15,200′.

There, they waited out one day of storm, then climbed up to 17,300′ on July 12th to set up Camp III.

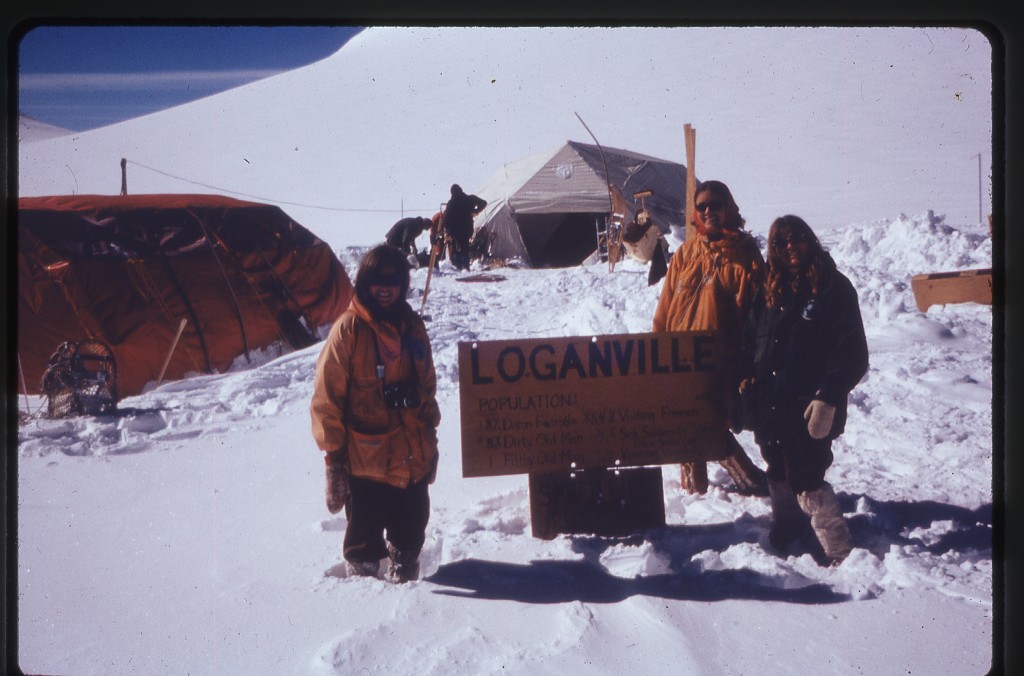

On the 13th of July, they moved camp with six days of food over an 18,000-foot pass and down to the Arctic Institute research station.

This station’s beginning was way back in 1966. Several groups collaborated to plan and construct this station, and, with the help of the Canadian military which flew in huge amounts of supplies and construction materials, an all-weather station was finished and occupied.

It sat at 17,500′ elevation, and had been in use for only 3 or 4 years by the time Barbara’s party arrived on the mountain. By 1983, the station had been completely removed.

They reached the station just ahead of a three-day storm. The other expedition arrived several hours later. The station generously provided food and shelter to all of the climbers. On July 16th, they moved camp three miles closer to the peak.

To put that in perspective, there is a summit plateau on Logan that is 15 miles long by 6 miles wide, which is surrounded by several summits. On this plateau, you can travel many miles above 17,000′ elevation. Some of the climbers returned to the research station, but the four that remained were able to take advantage of a 16-hour clear spell beginning at 2:00 PM the following day.

They reached the summit at 9:00 PM in sunshine and little wind, returning to camp by 3:00 AM, after a 13-hour round trip. Only Barbara and Dick Beach from her party, plus two members of the Oregon group, made it to the summit.

After the usual morning storm, they returned to the research station on July 18th and all the way back to base camp on July 19th. Due to storm and cloud, their plane couldn’t pick them up until July 22nd, and by Friday, July 23rd, they were all the way back in California – eleven days later than their planned return date!!

On a sad note, it was later learned that on August 20th, an avalanche struck the Oregon party as they were beginning their climb of Mt. St. Elias and four members were killed, buried under tons of wet snow. The fifth member, Toby Wheeler, who was one of those who summitted Logan with Barbara, managed to make his way back to the party’s base camp and was rescued after he sent out a radio distress call.

One year later, Barbara was ready to embark on an even bigger adventure, an attempt on Mt. St. Elias. Although at 18,008′ elevation it is far lower than either McKinley or Logan, it is considered a much greater challenge. Sitting on the Alaska-Yukon border, it is actually the second-highest mountain in the United States and the second-highest mountain in Canada. It is located only 25 miles southwest of Mt. Logan, and is known for its immense vertical relief, rising over 18,000 vertical feet in just ten miles horizontal distance from tidewater. The peak saw its first ascent on July 31, 1897, by the Duke of Abruzzi in a famous lengthy siege. The mountain had to wait almost fifty years to see its second ascent by the Harvard Mountaineering Club in 1946. It is infrequently climbed because it has no easy route to the summit and it has prolonged periods of bad weather.

Barbara knew that this could be her biggest mountaineering challenge to date. Mt. St. Elias was seldom climbed, and presented many challenges that were not to be found on either McKinley or Logan. In fact, her ascents of those peaks were merely warm-ups for this one. I mentioned earlier that for every climber who attempts Logan, 13 try Denali. For every climber who attempts Mt. St. Elias, 140 attempt Denali. History shows that 50% of those attempting St. Elias will summit. After first flying to Whitehorse, Yukon Territory on June 9, 1972, her party then traveled by bus and rented car to Kluane Lake. They had previously shipped their food and equipment to Whitehorse and had to pay Canadian duty to get it out of hock. After the seemingly-mandatory wait in the north, all six members of the party were flown by ski-wheel plane to Base Camp at 6,200′ at the junction of the Seward and Jeannette Glaciers on June 13. They had also arranged two airdrops on the Newton Glacier.

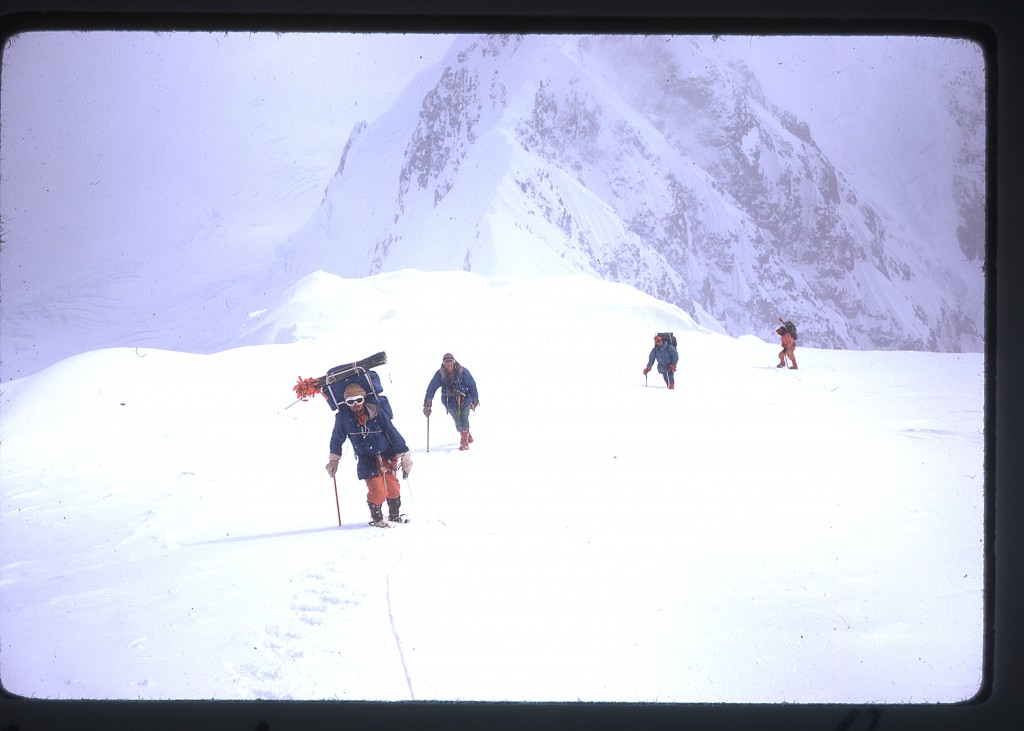

Then, following the route of the 1971 Oregon party, they ascended the five-mile snow slope up to and over Jeannette Col at 9,000 feet, then down steep snow on the south side to set up Camp I at 8,000 feet on June 13.

To avoid cliffs, the route of descent began several hundred feet southeast of the low point of the Col, dropped straight for the first 600 feet (a fixed rope could have been helpful), then went right diagonally down to the glacier. The next day, they retrieved a cache of food and fuel previously left on the Col.

After some bad weather, Camp II was established on June 17 by their first airdrop at 7,000 feet, above the Newton Glacier.

From there, they descended to the Newton Glacier at 6,000 feet by passing directly below the ridge extending southwest from Mount Jeannette and continued up the Newton to place Camp III in the uppermost icefall at 7,500 feet on June 20. Imagine this – they had already been climbing for one week, yet were only 1,300 feet above their starting point. Just getting at the mountain was a huge challenge.

Then, unable to find a route through above that point, they retreated to 7,000 feet and ascended the glacier between the east and southeast ridges of St. Elias, setting up camp IV at 8,700 feet on June 21. Eight days in, and they were still almost 10,000 vertical feet below the summit!!

From that camp, they crossed the east ridge at 9,000 feet and descended to the main Newton Glacier about half a mile above the upper icefall, where on June 25 they recovered their second airdrop at 8,600 feet.

The only obstacle on that route was a 30-foot icy overhang on the north side of the ridge, where it was necessary to place a fixed rope for climbing and hauling packs.

Spectacular avalanches were observed dropping thousands of feet down the north face of Mt. St. Elias (and also from Mt. Newton) and dusting the opposite sides of the upper Newton basin with powder. To minimize risk in the avalanche area below Russel Col, the climbers carried camp and five days of food through the upper Newton basin and up the steep slopes leading to and through an intricate crevasse field to Russell Col between midnight and 4:00 AM on June 26, arriving at the Col (12,300 feet) at midday. There, they set up their final camp.

Except for several one-day storms and some fog, weather had been good up to that point. However, as the altimeter read 13,000′, they were expecting the three-day storm which began that night – however, it did help with acclimatization.

Clearing began on June 30, so they left at 4:00 AM for the summit.

All six reached the top 14 hours later after 5,700 feet of elevation gain, in sunshine but with a temperature of -2 degrees F. The round trip from camp to summit and back to camp took 23 hours – fortunately, it was daylight all the time.

The next night, they descended from Russell Col, crossed the Newton Glacier, and climbed and hauled packs up the overhang where a fixed rope had been left. They then descended the side glacier to a camp at 7,000 feet. Leaving that evening, they completed the return over Jeannette Col and down to Base Camp by noon on July 3, and were picked up by the glacier pilot on the 4th to begin their return trip to California.

So, Folks, why have I spent all this time writing all of these words about Barbara Lilley? My original reason was to tell you about her amazing accomplishment of having climbed North America’s five highest peaks by the year 1972. I think it could be successfully argued that she was the first woman to ever do so. When I talked to Barbara before starting to write this story, I wondered aloud if any man had completed the five before she did. There are those in the climbing community who think she was the first one, period, to have done it. I have no proof of that, and it would be exciting to know whether or not it were true. Perhaps we’ll never know for sure. In any case, her accomplishment is nothing short of remarkable.

Those of us who are lucky enough to know Barbara know something else about her – she is a peakbagger extraordinaire. In addition to the major peaks she has climbed, which include Aconcagua and Kilimanjaro, there are several thousand others that don’t garner as much attention. Her name can be found in countless registers, and is a household word to any serious peakbagger in the United States. And she’s still at it, Folks. Recently, I found her name in a register she’d left on a desert peak just two years ago. I thought the peak unclimbed as I stepped on to the summit, so imagine my surprise and delight upon finding her register. Oh, by the way, she had soloed it – at age 83. Her determination is something to which we should all aspire, fellow peakbaggers, and I am honored to call her my friend.

Please visit our Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690