Crawling on my belly with my face in the dirt – I didn’t sign up for this, and I sure as hell hope it ends soon. It’s draining my energy, yet this climb has barely begun – it’s still so far to go to reach the summit, if I can even get there. As I peer into the gloom under the vegetation, I see something five feet ahead of me, hanging on a branch. It looks like one of those brightly-colored, striped caterpillars, but this one is huge – it must be five inches long. It’s directly in the path of my crawl, so I might as well have a look. As I get nearer, I see it’s a knife.

Some poor border-crosser, lost in this canyon even more so than I, must have left it – I’d guess it was snagged by a branch as he too struggled to get through this Sonoran desert jungle. I pluck it from its perch and put it in my pocket. Finding the knife got me thinking of why anybody trying to sneak into the U.S. would have come this way in the first place. The upper end of the canyon ended at a pass at 4,500 feet, with huge cliffs guarding its south side, It was hard to imagine anyone coming here from the south – curiouser and curiouser.

I’m in Arch Canyon, not much more than a mile from a touristy picnic area, but I might as well be on the backside of the moon. People walk a little way up the canyon to see its namesake arch, but I surely have taken the road less traveled. I got up at 4:30 AM, packed up camp, drove some pavement and then some dirt roads in the night to arrive at the trailhead. Normally I’m never near any trails when I climb, but for this peak today there was one going my way so I used it. There was just enough light to see when I started out, and I soon left the trail and ended up following the sinuous wash that was the floor of the canyon. It was easy going, but in places steep-sided with plenty of vegetation – perfect for hiding from prying eyes during the day and waiting for the cover of darkness to move on if you were sneaking into the country. About a mile and a quarter from where I’d parked, I left the main canyon and started up an un-named tributary coming in from the south.

Folks, I spend what most people would consider an inordinate amount of time studying satellite images from different sources, trying to learn about access, approaches and whatever else I might glean from those photos taken from those craft orbiting high above our planet. It’s amazing what valuable information you can learn from these, but equally amazing how deceptive they can be. Sometimes, try as I might, I miss clues and details – I might put too much weight on what I think I’m seeing, and make poor decisions. Today was one of those days.

Not far up the canyon, while it was still fairly wide and somewhat open, I came across this bone. It looked like a pelvis. My contact at the University of Arizona later confirmed it to be that of a human female. It was sitting out in the open on a rock.

It is a sobering experience to come across human remains. It put me deep in thought, wondering who she was, did she have children or family. what were her dreams? I left her there, on top of a boulder out in the open. When I returned home, I’d notify the authorities.

It looked to me from my studies that I could climb up this tributary canyon a ways, then scramble up its east side on to an open, gentle ridge and waltz my way to my summit. So, as I continued, the canyon floor began to noticeably steepen and the vegetation thicken. I kept scanning the eastern side of the canyon, but something didn’t make sense. My satellite research said this side should afford a straightforward scramble up on to a broad ridge. No such luck – it was an unbroken wall of cliffs. Here’s a picture I took hours later on the way back down.

I kept thinking that it must ease up if I continued higher up the canyon, but it didn’t. I was becoming frustrated with the worsening vegetation, the lack of a way up through the cliffs and what was looking more and more like a poor job I’d done researching this route. Finally, I spotted what looked like a possible weakness in the cliffs. Up I went, but the closer I got, the more clearly I could see that it was not meant to be. There I stood at the bottom of a slab which looked totally unappetizing – it was too steep and devoid of holds for my liking.

When you’re climbing solo, you must learn to manage risk. I felt that I might have forced my way up it, but one wrong move and it’d be over in a heartbeat – a fall would certainly be fatal. There are old climbers, and there are bold climbers, but there are no old, bold climbers. I’m an old climber, and I didn’t get that way by making too many bold moves. In over half a century in the mountains, I’ve lost several friends who’d made climbing decisions that were just a little bit too bold for the situation they were in. Today, I was not going to join their ranks. Better to know when to quit, to come back another day on a different route, than pay the ultimate price.

Disappointed, I made my way back down to the canyon bottom. Hopefully, if I continued up I’d find a better spot, one that’d offer a safer route on to the ridge. On I went, and as I did, the vegetation that choked the canyon bottom thickened. It was filled with catclaw and other things with nasty spines, and many types of brush and trees – a botanist would have been in seventh heaven. The canyon walls closed in and steepened, the climbing became tougher, the growth became nightmarishly bad. It was easy to see that the floor of this bizarre lost world would never see the sun’s rays. It was becoming downright claustrophobic. I had to find a way out, or go home.

I spotted what might be a break, a pillar of rock standing out from the east wall of the canyon. Maybe if I made my way up to the notch on its upper side, I could continue to the ridge. It was a hard-fought 150-foot climb, with loose Class 3 and nasty vegetation barring the way. By the time I’d gained the notch, with a mouth full of grit and boots full of crud, I was feeling like a whipped cur. Okay, catch my breath and survey the route ahead.

It was pretty disappointing – there was nothing that was obvious, but neither had the door slammed shut. It looked like I could continue some distance before the route disappeared around a distant rib of rock. Thus began several hundred yards of a new kind of hell. The first order of business was to drop down over a hundred feet of steep ground, so choked with vegetation that I often couldn’t see where I was putting my foot. This backfired several times when I punched on through to nothing but air. You know the bushwhacking is extreme when you can barely force your way through it, and every few minutes, as you stand there soaked in sweat, heart pounding and gasping for breath, you’re ready to call it quits.

Progress, if you could call it that, was painfully slow. Once, as I groped for a hold above my head on a small cliff, I dislodged a rock the size of a grapefruit. In a split second, it fell and hit me on top of the head,. It was my lucky day, if you can call having a five-pound rock bean you luck – it had a flat side, which hit me squarely, then bounced off. It didn’t even break the skin. Momentarily dazed, I stood there and realized this could have been so much worse. It reminded me of the time Brian Rundle and I had been rappeling down a wall on a remote desert peak when our rope dislodged a rock the size of a breadbox up above us. As it hurtled past, I flattened myself against the wall and it missed me completely, but it grazed Brian’s helmet, glanced off his hip, and hurtled into the abyss below. Either or both of us could easily have been killed by that missile, but it was not our day to die.

Glad to be unscathed, I carried on. My route left the vegetation, crossed a ledge and turned the rib of rock. Maybe this was going to work – I crossed some open ground and came to the base of some steep, open rock with lots of good holds and, Bob’s your uncle, ten minutes more placed me on the wide ridge I had sought. It had taken a full four hours for me to stand in my first sunlight of the day. Things changed for the better. I found myself at 3,600 feet elevation, the slope was fairly gentle and free of brush, and I thought I could see what must be the summit ahead. It was still eleven hundred vertical feet above me, but the worst of it was behind me.

A few cliffy areas cut across my path, but were easily climbed. My satellite-photo research had showed me what looked like a nice ramp leading up to the final saddle, but once again I disappointed myself. The ramp turned out to be a band of nasty cliffs, and I was forced to once again drop down into a brushy basin to outflank them from below. After paying more dues thrashing my way across this, I reached an open, sunny saddle.

All that remained was a final gain of 250 feet up an easy slope, and at noon I stood on the top of Peak 4740.

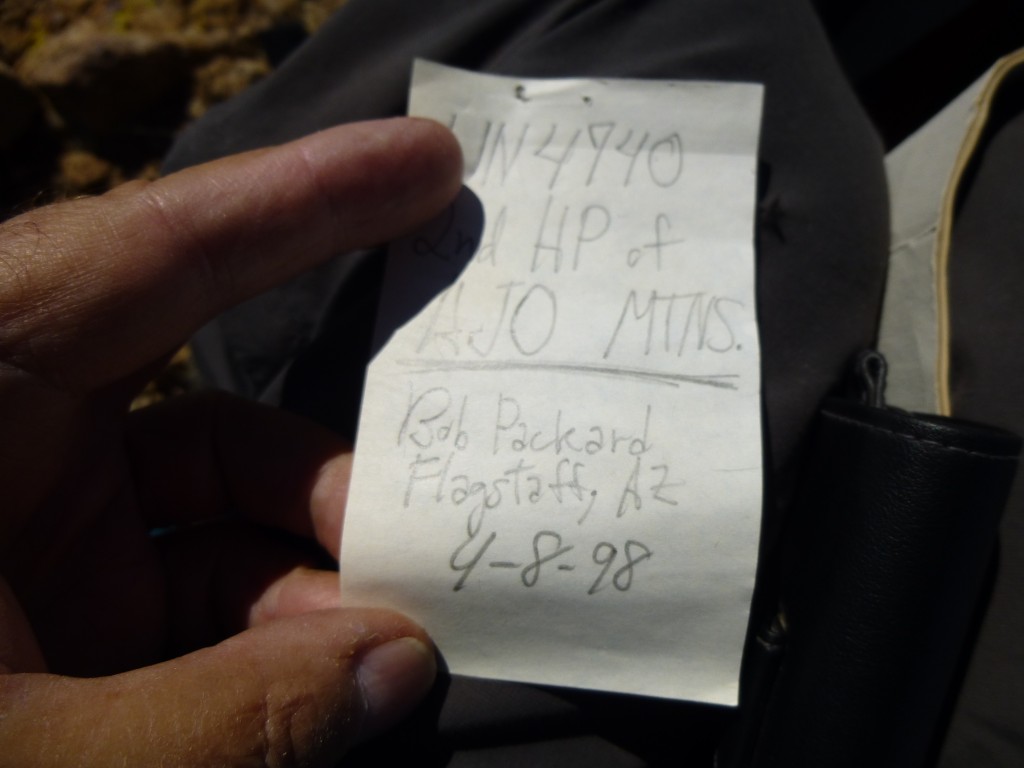

What a relief! It had taken over five hours to get here, and what a comeuppance it had been for me. Ah, the best-laid plans ……….. I found the summit register, which contained two entries (twice as many as I thought I’d find). The first ascender had been my friend Bob Packard from Flagstaff, Arizona.

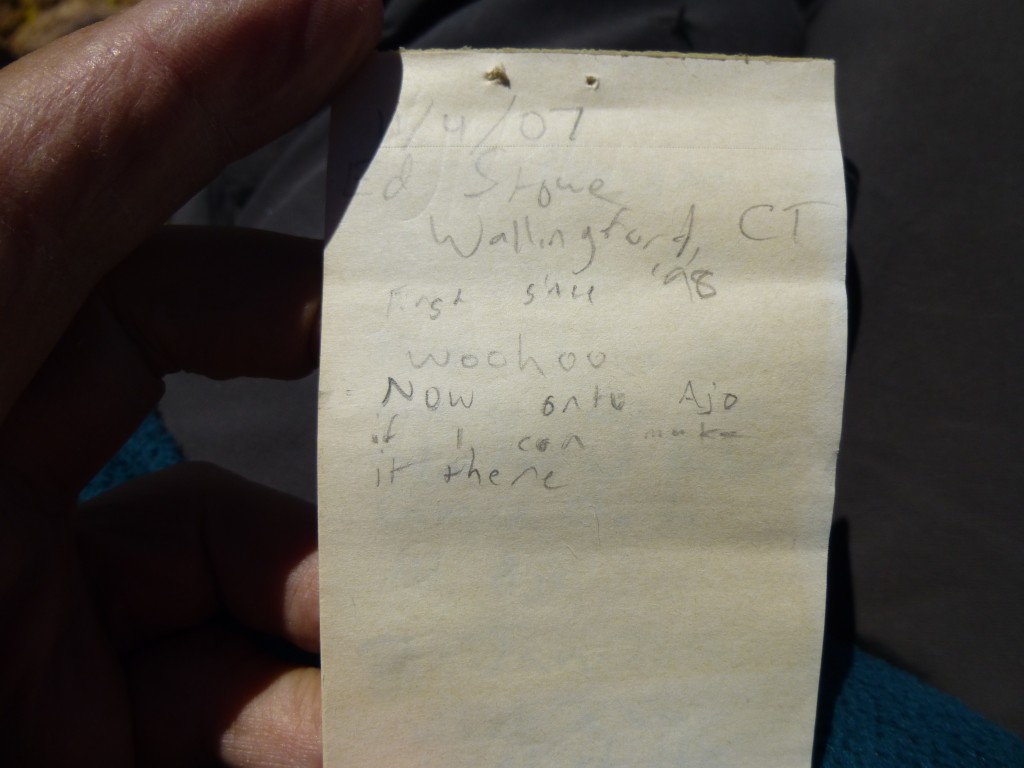

The second was one Ed Stone from Wallingford, Connecticut, whose entry stated he was going to then try to get to Mount Ajo, the range high point. It was only 1,900 feet away horizontally but I wondered if it was one of those situations where “you can’t get there from here”.

Most sides of this peak were guarded by massive walls of rock, as was much of Mount Ajo. If he made it, he was of sterner stuff than I.

It was comfortable on top, and I enjoyed a meager lunch in the sunshine.

After 20 minutes engaged in the usual summit rituals, I tightened up my boots and started down. Although it was tempting to try the canyon straight down from the 4,500-foot pass, who knows what problems lay below. I could easily be cliffed out at some waterfall and rue my choice. I’m not the risk-taker I once was, so I opted for for the sure thing. Down into and across the brushy basin I went, to re-gain the broad ridge – going down this was was definitely the most enjoyable part of the climb, free of difficulties and surrounded with million-dollar views. In the photo below, I’ll point out a few things. The red line that starts at the bottom of the picture shows the possible route I might have taken straight down the canyon. The dashed line means the route is hidden from view. The yellow line shows the route I actually did take – it goes steeply downhill into the brushy basin, then up the other side and on to the broad ridge, but almost immediately disappears again behind the ridge.

Something caught my eye – a bit of movement 200 yards downslope. I was amazed to see 3 desert bighorn sheep, a ram and two ewes. They ambled slowly away from me, after a minute disappearing from sight, but not before I snapped a few telephoto shots.

Although this was my first sighting of sheep in the Ajo Range, it made perfect sense they’d be here – much of the range is protected by huge cliffs, affording them the protection they need from predators. Seeing them made my day, a brief bit of serenity before the vegetated hell I’d soon enter.

When I reached the stretch of steep, open rock, I negotiated it ever-so-slowly (can’t afford a mistake here), then turned the rocky rib, crossed the ledge and re-entered hell on earth. The next photo is an attempt to show you my route across the slope and through the vegetation. The yellow line shows the route across the quarter-mile of hell – it drops way down, then up again, and it stops at the notch.

It was no less quick or easy to re-gain the notch, but finally, covered in dirt and scratches, I could look down into the gloom of the canyon below. The drop down from the notch was trickier than I remembered – maybe I was just getting tired. As I re-entered the perpetual shade, I was almost glad to be back in the tangle of growth, because I knew it was all downhill and straightforward from here. Here’s a look back up the canyon – it’s solid bushwhacking all the way up. See the big sugar-loaf rock in the middle of the canyon? My route went to the left of it.

Passing the pelvis, I knew I was almost back at Arch Canyon. Then, in the full light of the afternoon sun, what to my wondering eyes should appear but this spire, towering over the canyon floor. I hadn’t noticed it in the early-morning gloom, so focused was I on the climb up the canyon itself. Sweet Jesus, this thing was outrageous!! If you look carefully part way up the right side, that is a mature saguaro. I estimate that on its left (west) side, this spire towers a minimum of 350 feet from its base, and it could be another 100 feet or more than that. Now there’s a project for all the rock-jocks out there.

Here’s a view from down in the main part of Arch Canyon. It looks east up to the spine of the ridge heading north from Mount Ajo itself. All those crags are over 4,000 feet elevation.

I wound my way back down this main branch of Arch Canyon, sadly littered with the cast-offs of border-crossers, and arrived at the parking area by the picnic site. I changed into cleaner clothes and realized it had taken over nine hours for my little outing. As I write this, two days later, my arms and legs are covered with cuts and bruises (it looks like weasels ripped my flesh) and I ache all over. Peak 4740 is not for the faint of heart. If there’s an easier way up it, I’d like to know.

Here are a few photos of the canyon’s namesake arch, actually a double, seen to advantage from the trailhead.

Two hours later, I was back at my camp in Alamo Canyon, where I met Dave. We started to talk, and when I asked him where he was from, he pointed to his motorcycle. He then explained that he had no house on the hill, no trophy wife and no big retirement account. Rather, for the past 16 years he had traveled around on his bike, camping out and seeing the sights, beholden to no one, and said that if he had to do it all over again, he wouldn’t change a thing. An interesting philosophy, for sure. In my climbing life, I’ve always felt that I’ve got to go for the goals that matter to me, and to do it with gusto. As my favorite wordsmith, Bobby Dylan, says “He not busy being born is busy dying”. Words to live by.

Here’s a bit of an update on the pelvis. I contacted the authorities at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, and they went out and examined the site. They were unable to find any other remains in the immediate vicinity. They had no open cases regarding missing people in the area, so the possibility of it being a migrant death is strong. As far as their age, it’s incredibly hard to say and really depends on how long the bones were out in the open, what their environment of original deposition was and what scattering events occurred. Also, the primary management of the case has been turned over to Pima County.

Please visit our Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690