A long, long time ago I lived in British Columbia, Canada. It was a climber’s paradise – I was surrounded by endless peaks of every description. Although I had plenty to climb right around home, I lived only 8 miles from the U.S. Border and often turned my attention in that direction. The North Cascades were bristling with mighty fine summits, and I tried hard to get my share of them. One of them I had pondered for many years was Mt. Shuksan, arguably one of the most photogenic peaks anywhere. It has probably appeared on more calendars and T-shirts than any other mountain.

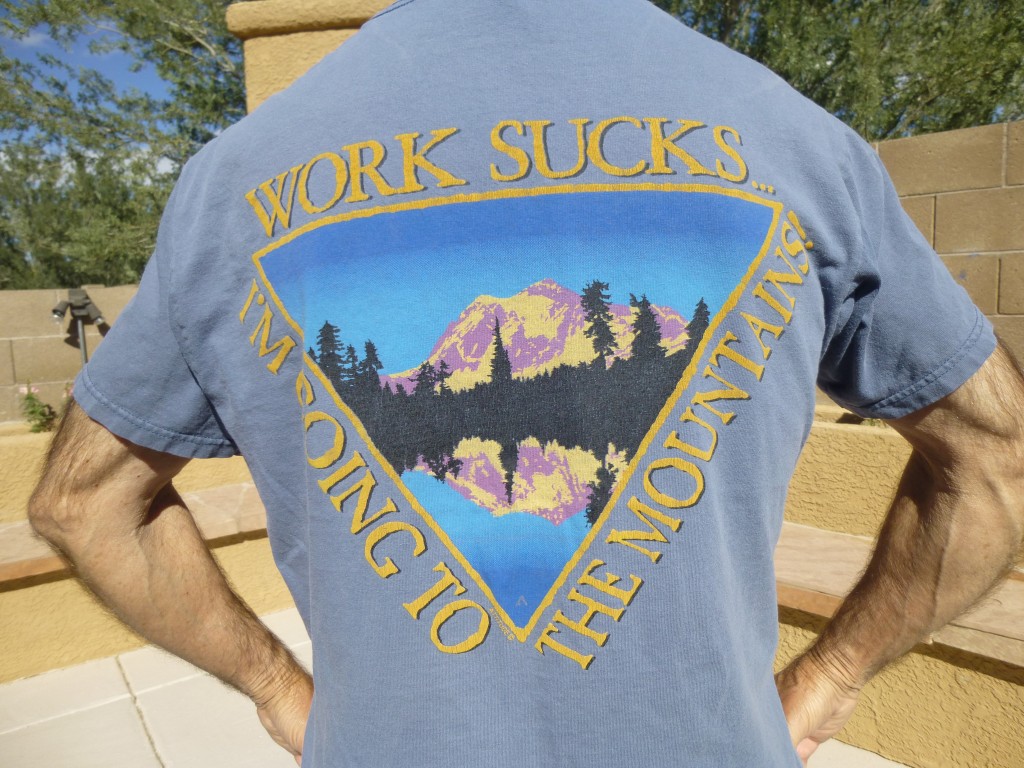

Its oft-copied image has even been ripped off by others – here’s a shirt from Keystone, Colorado, which says “Work sucks, I’m going to the mountains”. I love the wording, but for Keystone to pass off this image as something that is in their neck of the woods – well, it just ain’t right.

Not only is it beautiful to look at, but it’s a great climbing challenge. Fred Becky, in his Cascade Alpine Guide: Rainy Pass to Fraser River, sums it up as follows:

“Mt. Shuksan epitomizes the jagged alpine peak like no other massif in the North Cascades… it has no equal in the range when one considers the structural beauty of its four major faces and five ridges…There is no other sample in the American West of a peak with great icefall glaciers derived from a high plateau, and in the Pacific Northwest it is the only non-volcanic peak whose summit exceeds timberline by more than 3000 feet… Shuksan is one of the finest mountaineering objectives in the North Cascades and its reputation is certainly deserved; a wide variety of challenges can be encountered on this quite complex mountain. The climber has a choice of rock walls, moderate firnfields, steep ice, and easy scrambling. Despite a sometimes-forbidding appearance, Shuksan has yielded 14 routes, numerous variations, and impressive subsidiary climbs, including some directly up dangerous ice cliffs.” – Fred Becky (Cascade Alpine Guide : Rainy Pass to Fraser River).

A few more interesting facts about the mountain are these: Shuksan is one of the most photographed mountains in the world for its striking beauty and easy access. It is ranked #13 on the list of Washington’s highest peaks (#10 on the Bulger List), #60 on Washington’s Steepest, is on Fred Beckey’s “Great Peaks of North America”, and has 4,411 feet of Prominence. It also has a route listed on North America’s 50 Classics list.

Shuksan (which means “high peak” in the local Lummi language) tops out at 9,131 feet elevation. It wasn’t visible from my BC home, but almost. Mt. Baker, its nearby higher neighbor, was easy to see, but Shuksan was hidden by intervening mountains. It wasn’t hard to drive there, though. Once through the border crossing, it was a quick 40-mile drive through beautiful wooded country to park at about 4,800′ at a trailhead. Anyone who’s gone in to try Shuksan by the usual route, which starts with the trail to Lake Ann, knows that the beginning of the climb sucks, because the first thing it does is lose 900 vertical feet. On the way back out after a hard climb, that uphill slog back to your car really crucifies you.

So, on October 19, 1976 I decided I couldn’t wait any longer. I drove from my home to the trailhead and spent the night sleeping in my Volvo station wagon. The next morning in an hour and a half I made it in to Lake Ann, then kept right on going, intending to do it as a day climb. Try as I might, I finally stopped at 7,500′ – the risk of falling into a crevasse, solo and unroped, just wasn’t worth it – I could always come back.

However, by the summer of 1977, I had met Brian Rundle – this was a life-changing event, as we would go on to climb many significant peaks over several decades. Within weeks, we had climbed Mts. Lindeman and Outram, and as only our third peak we had set our sights on Shuksan. We were young and sassy, and felt we were more than ready for whatever the peak had to throw at us. On June 10, we drove to the trailhead and packed in to Lake Ann at 4,700 feet. The weather was perfect – clear blue skies, just the right temperature. We spent the afternoon relaxing at our campsite in the meadow, psyched for the climb.

By 4:00 AM we were up and moving. The tent, we just left standing in the meadow with all our camping gear inside it – those were the days when you didn’t have to worry much about such things. The climb began by following a trail of sorts up through open alpine country to gain a thousand feet. That brought us to the base of what are called the Fisher Chimneys. These are more like steep, loose gullies – there’s plenty of exposure, and you’d better be paying attention, because some folks have died there who weren’t. You need to find the right way up through them, too. Class 3 for sure, and possibly Class 4 depending on which way you go. By the time you exit the chimneys, you’ve climbed another 800 feet and have reached about 6,700 feet elevation. There, we roped up and continued southeast on the Upper Curtis Glacier.

Having gotten to this point, a decision needs to be made, as two main routes are accessed from here and they couldn’t be more different from one another. One involves heading south to outflank the southwest ridge of the peak, then climbing up on to the Sulphide Glacier. This route is commonly referred to as Hell’s Highway. The other route that we could choose was called the Hourglass, which is the ice climb that forms in the notch to the west of the summit pyramid. In the next photo, the Hourglass is the steep, narrow gully choked with ice that can be seen on the right center of the photo – it climbs from the Upper Curtis Glacier up to the upper part of the Sulphide Glacier which can be seen on the skyline. Hell’s Highway follows the glacier down and to the right, disappearing off the photo, then eventually reappears, climbing from right to left above the large rock outcrop on the right and up the Sulphide Glacier. From the bottom of the Hourglass to the top of the summit pyramid is over 2,000 vertical feet.

For some reason I can no longer remember, we chose the Hourglass – feeling our oats, I guess. Once we got close to it, we crossed the bergshrund at its base and continued up. We put on crampons and had ice axes in hand. Once we got up a ways, we noticed that there was another party ahead of us. That didn’t have to be a problem, but they were knocking a bunch of ice loose and it was coming down in our direction, and that was a problem. We weren’t wearing helmets, so a chunk of ice to the head could be fatal. Now we really did have to make a decision, and fast. As committed as we were that high up, we sure as hell didn’t want to descend and take Hell’s Highway to go around – we had already decided to minimize the risk from crevasses. So, we did the only thing we felt we could do – we unroped.

Now what? We moved over to the side, off of the ice proper, and on to the rock. To this day, I remember several things about our situation: the rock was steep; the rock was crap; the exposure was severe; the rock had a thin coating of ice. A fall there, unprotected as we were, would have certainly been fatal. It was climbing that had our full attention. I felt pretty stoked, just wanting to climb up and out of the situation and be done with it. I wasn’t afraid, but maybe I should have been. Although I have no memory of it, Brian says that we both took on “affected and outrageous” Scottish accents as we climbed up and out of the Hourglass on the walls of the Southwest Ridge. After a while, things eased up and we found ourselves on the relatively flat terrain of the Sulphide Glacier at around 7,700′.

We roped up again and continued north up the glacier without incident. Arriving at the base of the steep summit pyramid, we unroped once again and climbed up its 800 vertical feet of rock, at times Class 3 and quite exposed, to arrive on the summit of Mt. Shuksan eight hours after leaving Lake Ann. The weather was warm and clear, and we relished every moment on the summit – the views were outrageous – but we didn’t linger long. Miles to go before we sleep.

The return was via Hell’s Highway, which suited us just fine, as we didn’t feel like downclimbing the Hourglass. Each of us took a turn breaking through the snow cover on the Upper Curtis Glacier into a crevasse, but both times were minor and we forged ahead. Downclimbing the Fisher Chimneys was another pretty gripping experience, as we were pretty tired. At 5:15, we were back at our camp, and by the time we’d packed up and made it back to my car it was 8:30. Two more hours saw us across the border into the Great White North and home. It had been a great climb, one of the more memorable ones.

Please visit our Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690