Please read the previous 3 installments of this story before you continue here.

Day 5 dawned clear and cold, but we were up long before dawn. After our usual hot breakfast of porridge, we packed up our camp, hid it all under our nearby Palo Verde tree, and set out by headlamp. It was going to be a long day, even though we had only two climbs remaining. Today, Mark and I were heading out to what we called the “Western Aguilas”. This was a small area with only two peaks, but it sat apart from the rest of the range.

It was another 3-layer day, with the temperature hovering around freezing. After a few miles of westerly march from camp, we approached our first peak. The first rays of sun were touching its summit as we approached.

We picked up the northeast ridge, visible on the right in the above photo. It turned out to be enjoyable, with some interesting rock formations along the route. Obviously, the 600-foot climb with no difficulties didn’t take very long, and we soon stood on the summit of Peak 1266. Of the 13 peaks in the range, 6 of them were in Yuma County with the remainder in Maricopa County. This was the most westerly of all of the 13. From the summit, we had this view north. On the left, we see the northern Aguilas in the far distance; on the right, we see the western end of the central Aguilas nearer to us. Very close in sits Point 878, the 200-foot bump down below us.

As we looked south, we could see much of the western Aguilas.

After a brief visit, we scrambled down the east side of the peak to reach a valley at 680′ elevation, where I took this picture looking back.

As we dropped down the east side, a couple of F-16 fighter jets flew overhead and released some kind of flare we hadn’t seen before. Unlike the orange parachute flares often seen at night, these were bright white and small, and burned themselves out very quickly. Also, there were many of them.

It was short work to climb Peak 1090, a short distance to the east. It was a bittersweet moment as we pulled on to the summit – joyful because we were done, and sad because we were done. Our dream of climbing every peak in the Aguila Mountains had been realized, against all odds. A register had been brought all this way for this last peak, and we dutifully placed it inside the cairn we built. Each of the registers (a glass jar covered by a can) we had laboriously carried now sat on a different summit in the range. We congratulated ourselves on our feat and had a snack, then found a way down the north side. A couple of easy miles had us back to camp by 10:00 AM. Here’s the spot where our camp sat for those wonderful days, just to the left of the big tree.

Since we were already mostly packed, it was the work of a few minutes to prepare our big packs and head out. It would be a straightforward march back to our first camp near Eagle Tank – two brief uphill stretches, but mostly downhill walking. Our packs were lighter than when we’d come in on Day 2, but still too heavy for our liking. We walked past the tank, our suspect (but still much appreciated) water supply for the last 3 days, then up the wash and into the gap which had given us access from the central part of the range.

The weather was perfect, and we were soon walking past the starting point for our climb of Peak 1750, the range’s second-highest. This valley was filled with spectacular scenery, easily the best of the entire trip.

Unusual rock formations were all around us.

As we neared the spot where we’d have to do the last bit of uphill, Mark suddenly grabbed my arm and whispered to me to look to the north. There, finally, we saw what had eluded us for days – desert bighorn sheep. No rams, but several ewes and their lambs of different ages. They looked at us for several minutes, seeming unafraid, before they moved over a saddle and north, in the same direction we were headed. We counted 13 of them before they disappeared from sight. What a treat! We felt that our experience was now complete. It can be hard to see these elusive creatures, as they usually see and hear you long before you do them.

Thirteen seemed to be our lucky number: 13 peaks; 13 sheep; 13 pinnacles in the feature we called “The Feathers”. We continued up the hill to where the sheep had stood, then down the other side to the north. As we followed their tracks for another half-mile, we had shit-eating grins on our faces that you couldn’t have wiped off with a baseball bat – we had seen our sheep. The terrain was changing again, becoming more gentle.

Half an hour later, we walked right in to our first camp. True to their promise, our Border Patrol friends had put everything back where they had found it – our food, water, fuel and clothing was all there. Yay! Once we saw that the world was right, it was time to do something we’d hoped to have time for – a visit to Eagle Tank itself. An easy walk of maybe a third of a mile back to the south brought us to a steep narrow canyon.

At the base of the canyon sat this pool, a natural desert tinaja. As you can see, a pile of sediment filled much of the volume of the pool, reducing its volume.

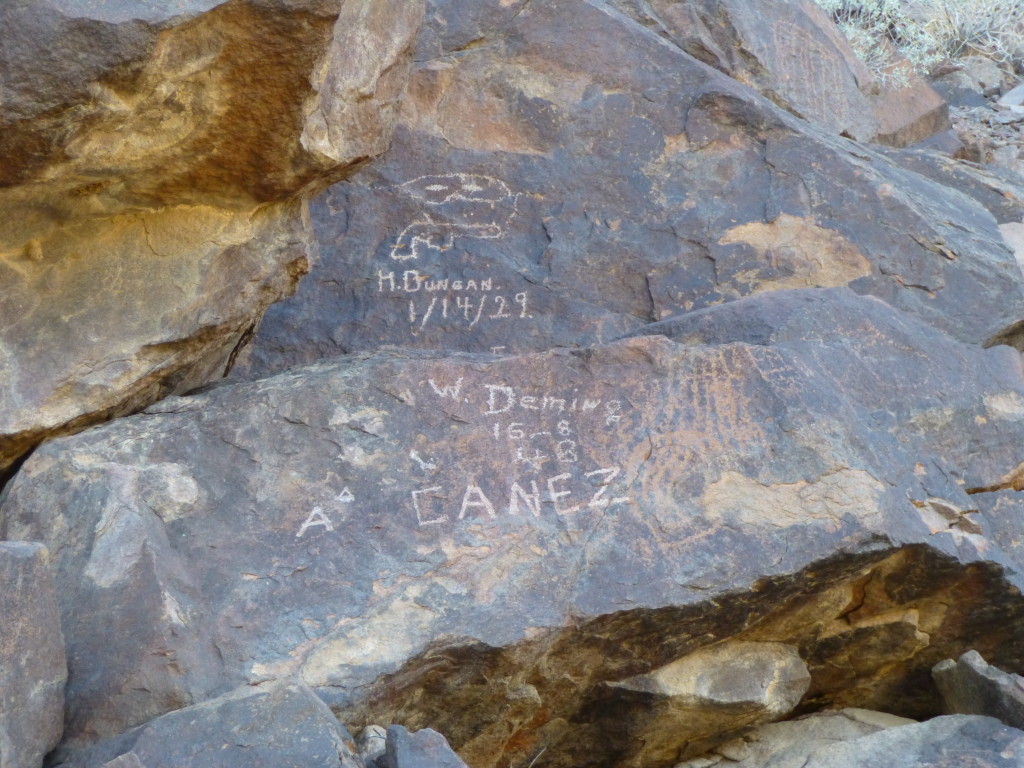

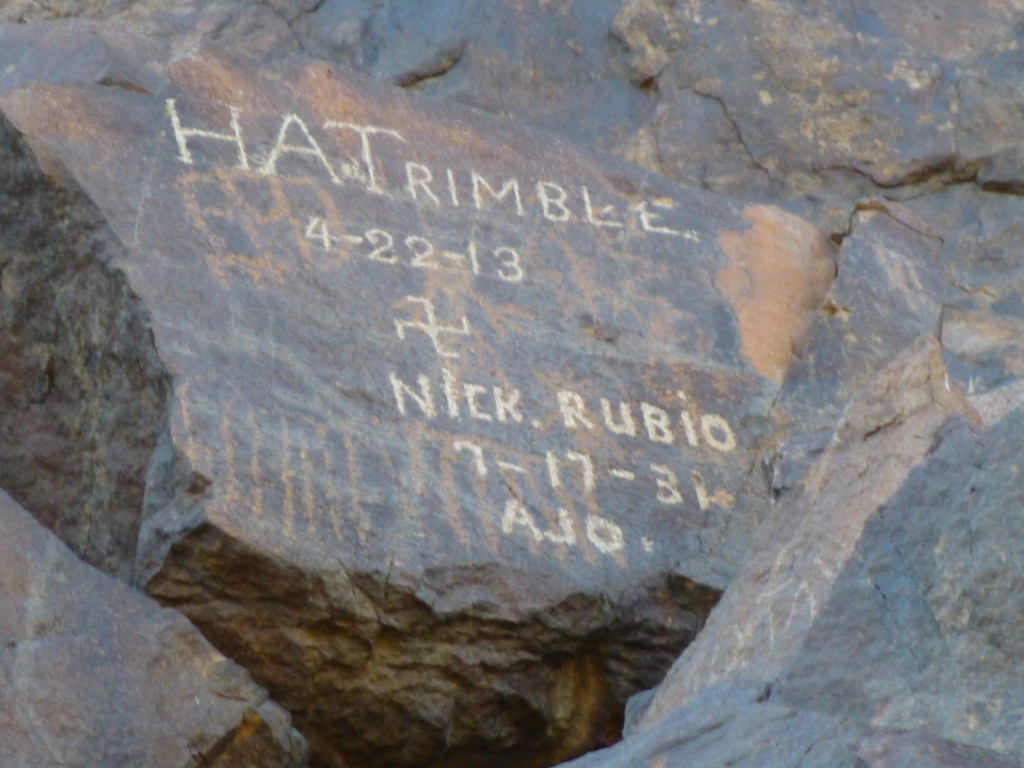

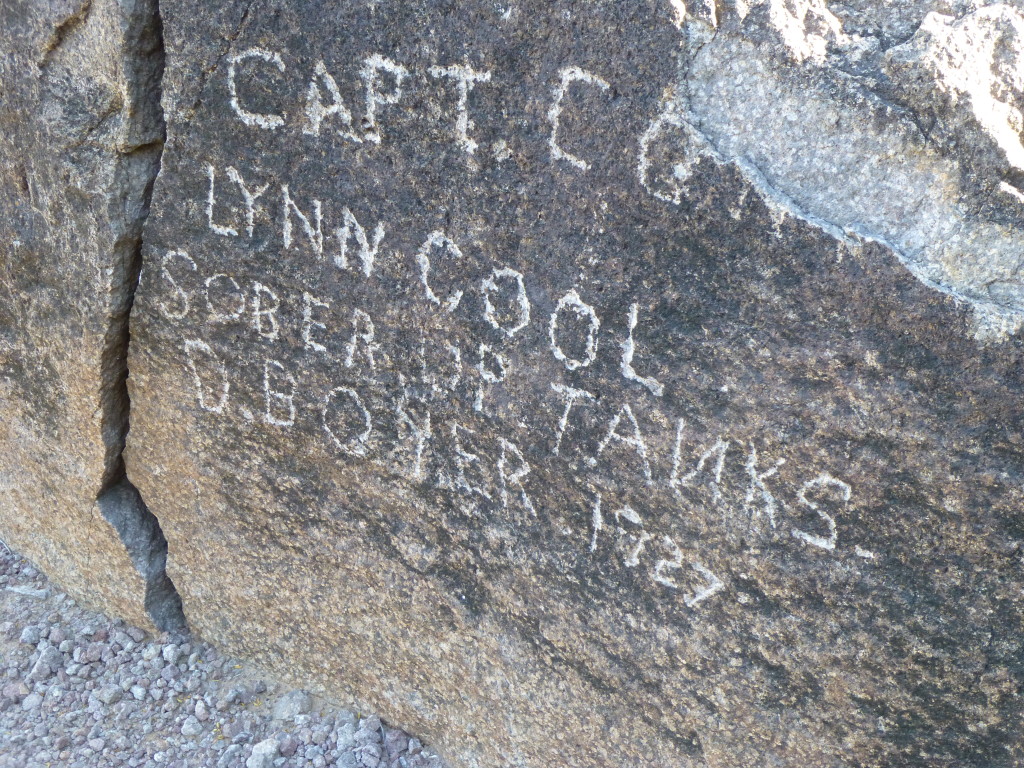

Eagle Tank can hold water for some time after a rain; nevertheless, it still can be unreliable as a water source. Historically, though, it has been known as a life-saving, sometimes-supply in this parched area of desert. As we poked around in the area of the pool, we saw that many of the boulders sitting there had names scratched on their surfaces. It was obvious that many had visited this spot for a long time. I saw dates from: 1902; 1909; 1910; 1911; 1913; 1917; 1927; 1929; 1931; 1932; 1936; 1948. Check out some of these wonderful mementos.

Sadly, some ancient Indian petroglyphs on the rocks had been defaced by these more recent signatures. In any case, we spent an enjoyable time there before walking back down the old road to our camp. Here’s a last look back at the Feathers to the south.

You can see how things really open up as you enter the northern Aguilas.

After setting up camp and cooking a meal, we had an enjoyable couple of hours around a campfire. That night was cold, so much so that our water bottles were frozen in the morning.

The next morning, we arose well before dawn, ate porridge for the last time, packed up camp, and rode away by headlamp with 40-pound packs on our backs. It took a while, but the sun finally rose.

There’s not a lot to say about the ride out. It was misery. Slow, painful. Once the sun rose, a bit of warmth started to return to our bones as mirages danced on the eastern horizon. Even with the feeble winter sun shining on us, I wore four layers on top for hours. As we rode on, our butts got sore, very sore. At the beginning of the ride, we were able to ride for a mile, even two, without stopping. The terrain was sometimes challenging, and when it became sandy all we could do was get off and walk the bikes – that actually gave our sorry asses a welcome break.

As time passed and the ass-pain increased (even with my padded bike seat), our riding time between breaks decreased. About 4 hours into the ride from hell, there were still ice crystals in my bottle of Vitalyte, which had been on the sunny side of my pack the entire time. God, how we longed for a time we could get off those bikes once and for all!! Well, even rides from hell must end, and after 5 hours ours did. Those trucks of ours looked mighty fine.

We had done it. A clean sweep of the entire range, Mark and I had now stood on the summit of every peak in the Aguila Mountains. Twelve of them were first ascents, with registers left on all of them. Who knows how long it’ll be until another climber signs in to any of them – a year, a decade, a century? Maybe never – it’s possible.

Our little adventure took 6 days. We had biked 44.5 miles, and had covered 50.4 miles on foot. Was it bold? – you bet!! In retrospect, would we do it again? – absolutely. In mountaineering, you can’t get the big prizes unless you’re willing to lay it all on the line. That’s what Mark and I did in 2014 in the Granite Mountains (see Granite Mountains Expedition on this website) and we did it again in the Aguilas. Perhaps the most important requirement in such an undertaking is the right partner, and Mark’s abilities as a mountaineer make him the perfect choice, as well as his mindset for this grueling type of project. Thanks again to him for his patience and skill on every step of this little adventure, and for the use of many of the photos that you’ve enjoyed in all 4 parts of this saga.

Please visit our Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690