Howdy Folks – in order to get the most from this story, please be sure to read the first 11 chapters that preceded this one on this website.

Monday, January 21, 1991

After a good night’s sleep, I was up by 5:00 AM. The tourist excursion bus arrived at my door at 6:15 and away we went. It was packed with tourists like me from several foreign countries, as well as Argentines from the big cities in the north such as Santa Fe, Rosario, Córdoba and Buenos Aires. We were all excited, as this clunky old bus was taking us to one of the most famous mountain places in the world. It was a journey of 225 KM of dirt roads, requiring 5 hours of bumpy travel. We passed to the east of Lago Argentino, then traveled for miles along the valley of the Río La Leóna. This brought us to Lago Viedma, its 50-mile length sitting at an elevation of 820′ above sea level. As we started northwest along the lake, we had our first good views of the distant high peaks of the Andes.

From the same spot, here was our view looking northwest up the lake, a glimpse of the excitement to come.

More miles passed, and our driver stopped so we could take pictures across the lake to the Viedma Glacier. It flows many miles from the vast South Patagonian Icefield, and its snout is over 2 KM wide where it calves into the lake.

Oh yes, a couple of things I forgot to mention earlier. During the long bus ride, we saw many guanacos and ñandus (rheas, a large flightless bird) that made things more interesting. Also, back in El Calafate, I’d rented a sleeping bag and pad for 6 bucks, as I was planning to stay overnight up here. Finally, the bus stopped at El Chaltén, a tiny community of perhaps 100 souls. Why was I here – simple, really – I had come to see Cerro Fitzroy, one of the world’s best-known mountains.

I’d first heard of it as a young man, and all my life it had a certain mystique about it – and now here I was, on the verge of seeing it for the first time. When I got off the bus, I quickly made the acquaintance of Daniel Renison and, as he was heading the same direction as I, we set out from El Chaltén together. Daniel was a PhD student, studying the Magellanic penguins at the huge colony at Punta Tombo on the Argentine coast. An Argentine by birth, he had grown up in an English-speaking home in Córdoba, and so was perfectly bilingual. Throughout my 7 weeks in Argentina I had spoken nothing but Spanish 24/7, so it was a relief to actually speak English for a change. El Chaltén sits in an amazing setting of forest, rivers and mountains, and it lifted my spirits to be surrounded by so much beauty as we set out on a fine trail.

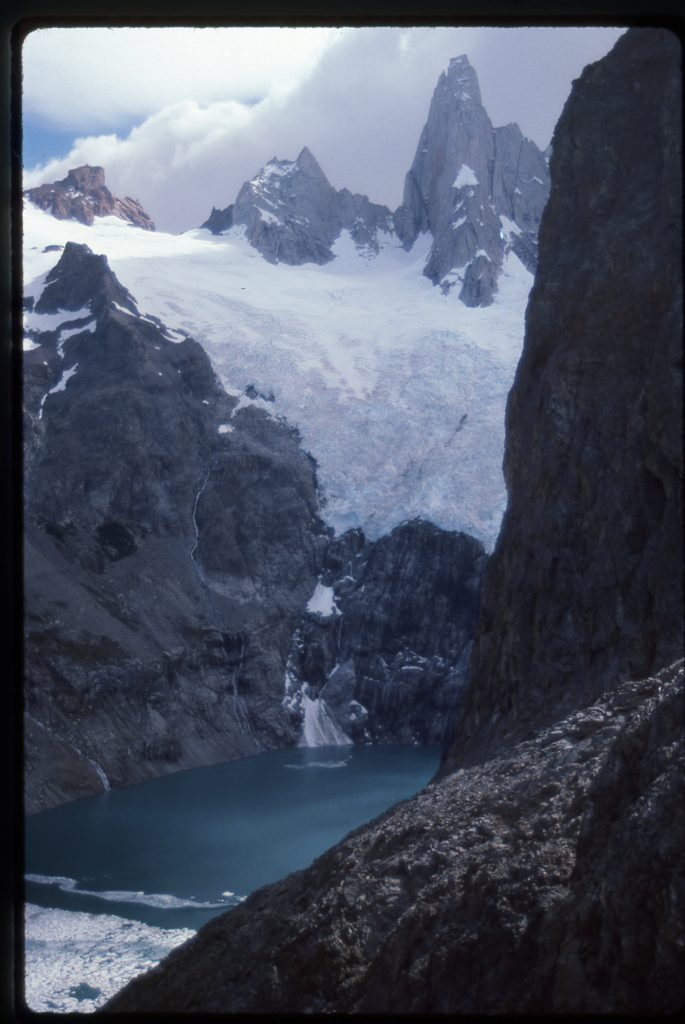

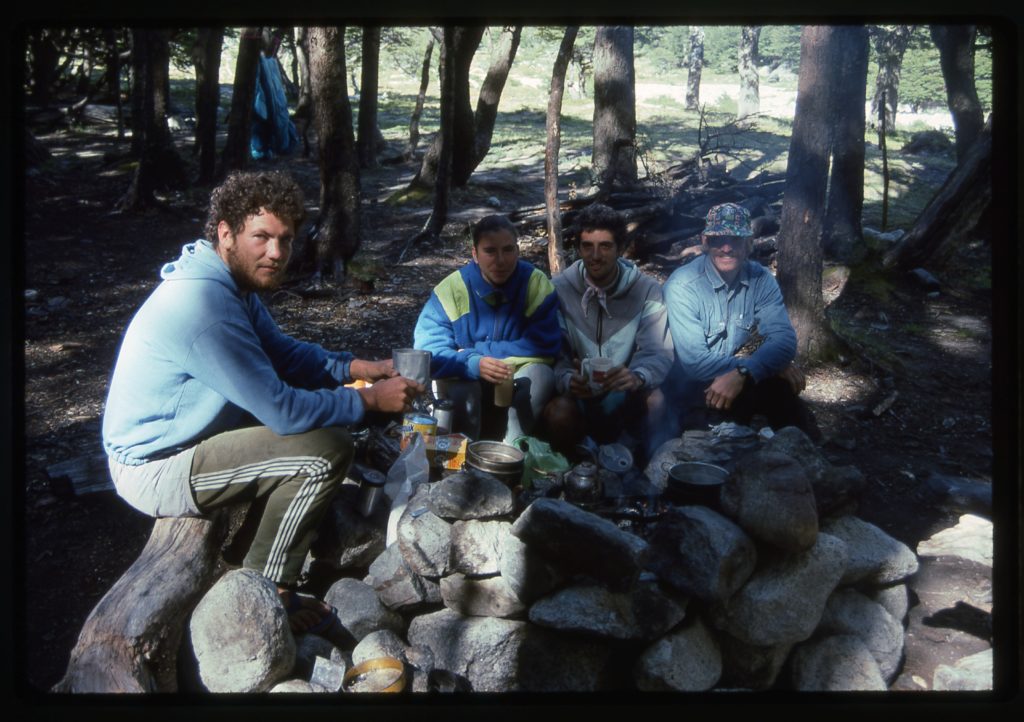

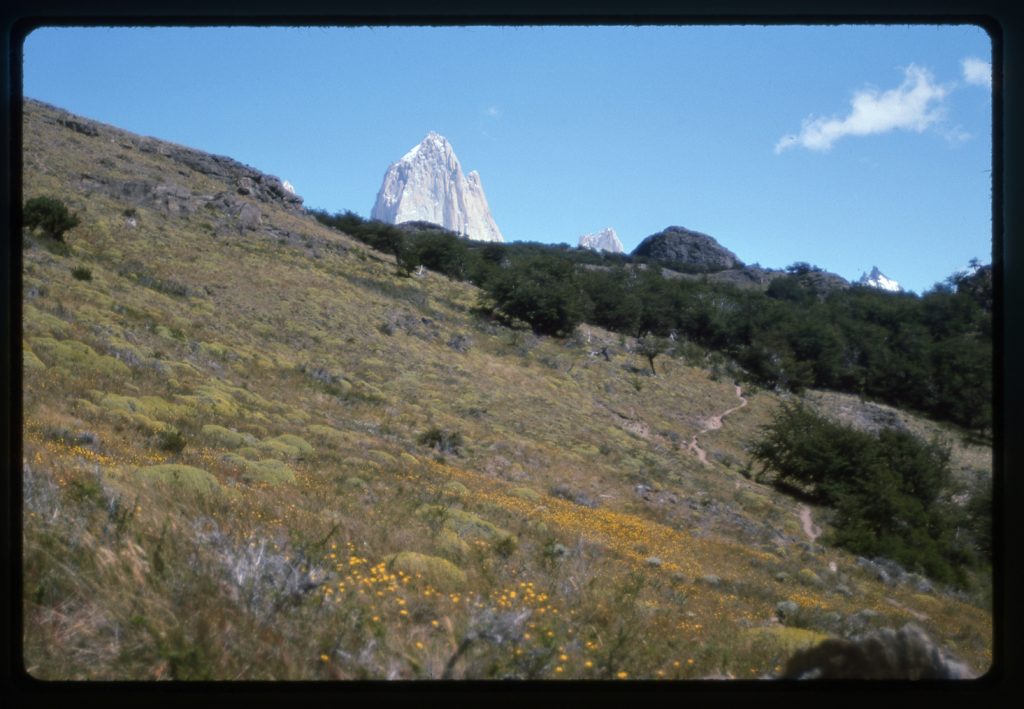

Three hours of hiking with a lot of ups and downs brought us to a spot known as the Poincenot campsite. Daniel had come here to hang out with his climber friends, who had been camped here for an entire month waiting for enough of a break in the weather to attempt Fitzroy, to no avail. Daniel had a tent and offered to share it with me, so we set up camp in the forest. There were parrots nesting there, one of them in a high tree right beside the tents. Shortly after arriving, Susana and her boyfriend Julio and I made a quick 1,000-foot climb up to Laguna de los Tres. Part of the way up, this view greeted us. The photo was taken at around 3,700′ elevation. We are looking down to Laguna Sucia at 2,950′. The steep spire to the right of center is Aiguille Poincenot (9,850′), and the lower one near the center is Aiguille Rafael (8,150′). It’s deceiving, isn’t it – Poincenot rises 6,000 vertical feet above us.

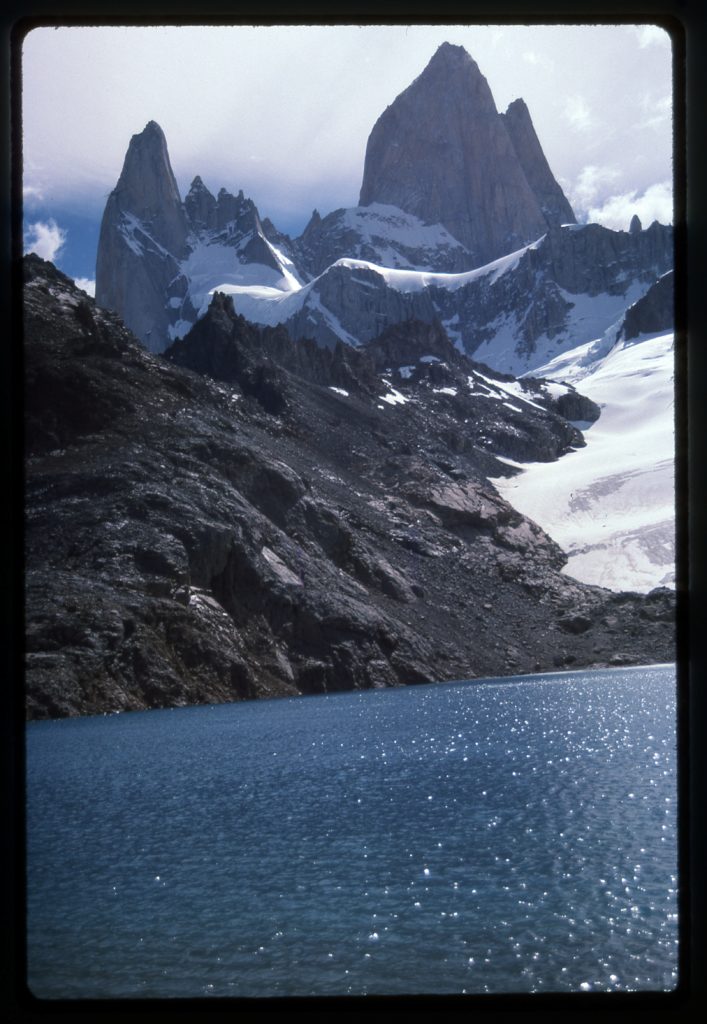

But here’s an even better view, taken from the shore of Laguna de los Tres at 3,840′.

Staying only long enough for a few photos, we quickly descended to the campground where we stayed up really late drinking endless cups of tea. They were great company and of course we exchanged addresses. The following austral winter, I made a return visit to Argentina and spent an enjoyable week with them all in Córdoba.

Tuesday, January 22, 1991

We slept until late the next morning, but sadly, my time was very limited and I had to leave.

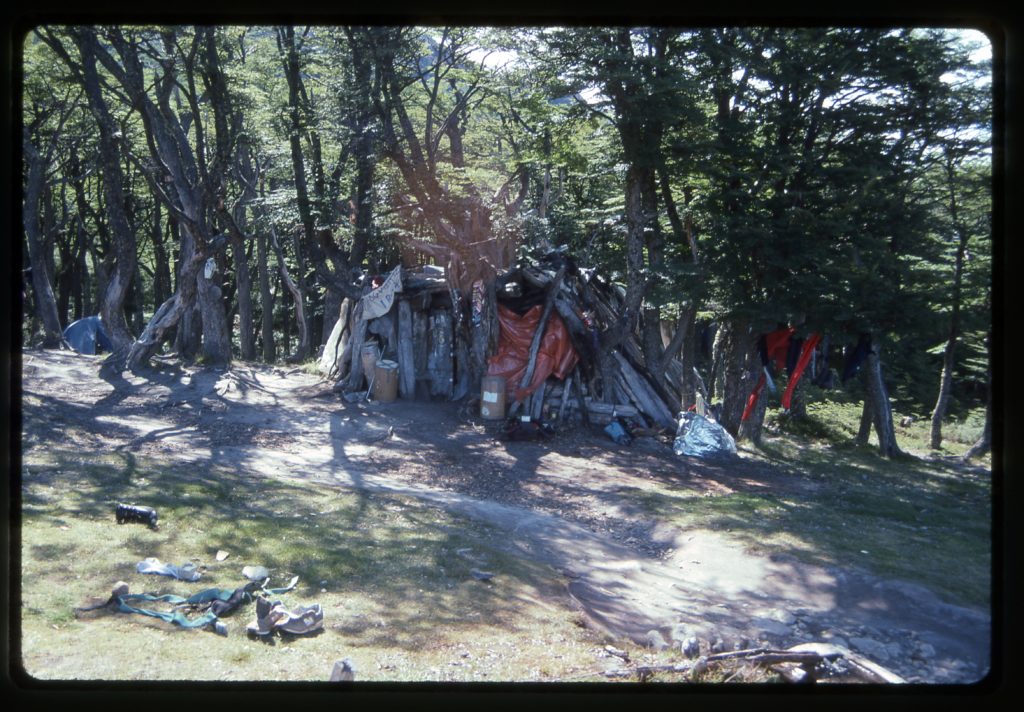

I also wanted to show you this photo – it’s a hovel that climbers were using as a base camp near the Río Blanco – a pretty depressing place to stay for weeks on end.

A couple from New York was also staying at the campground, and we walked together back out to El Chaltén.

I haven’t forgotten that the name of this chapter is Fitzroy, so now it’s time I told you more about the mountain. It’s named after Captain Robert Fitz Roy, the captain of the HMS Beagle, Charles Darwin’s ship of discovery. On April 13, 1834 the Beagle anchored in the mouth of the Santa Cruz River on the Atlantic coast. Three boats set out on April 18, carrying twenty-five men, including the captain and Darwin himself. All involved took turns in teams dragging the boats up river for 16 days. Their efforts took them 140 miles inland from the Beagle. Swift water and rugged canyons made it apparent they could go no farther with the boats, so they turned around. If they had gone a little farther, they would have discovered that the river flowed out of Lago Argentino, and that the Río La Leóna flowed out of Lago Viedma and into Lago Argentino. The first European to actually see the mountain was the Argentine explorer Francisco Moreno, on March 2, 1877. The mountain is today so revered that it appears on the coat of arms and the flag of the province of Santa Cruz in Argentina.

Argentina and Chile have been arguing about the location of their mutual border just about forever, and perhaps no more so than in this area. They have agreed that their international border detours eastward to pass over Fitzroy’s main summit, but a large part of the border to the south of the summit, as far as Cerro Murallón, remains undefined. Fitzroy, with an elevation of 11,171′, hardly ranks among the world’s giants – instead, it owes its reputation to its amazing appearance and its notorious weather. It sits on the eastern edge of the South Patagonian Ice Field, and climbers know that its weather is truly legendary. Here’s the best example I can give you of that, a telling of the mountain’s first ascent.

It was 1952, and not much mountaineering had been done in the Fitzroy area. A French team became fixated on the idea of journeying to the peak (which was no small matter in those days) and putting up the first ascent. Their team was welcomed with open arms by General Perón himself, and the Argentine people greeted them enthusiastically. However, once out of the capital, their expedition started to run into difficulties. Bad weather and a sick gaucho kept them waiting for their pack animals for a week. In order to make up for lost time, Jacques Poincenot and Lionel Terray set out on a reconnaissance. While they were crossing a swollen stream, Poincenot was swept away and drowned. This was a devastating blow to the team – they debated whether to abandon the whole thing, but after 2 days decided to continue.

The only people living in the area were sheep farmers, so there were no porters available. The team was forced to carry more than a ton of supplies in on their own backs to their base camp. At times they fought against powerful storms with winds of 125 miles per hour. Their Camp One was torn to shreds by these winds, forcing them to dig a snow cave, and much time was spent every day renewing the trail from camp to camp in knee-deep snow. In spite of all the adversity, they were able to set up three camps and stock them with food and gear. It was a long way in to Camp Two, but not too difficult. However, the last thousand feet before Camp Three were another matter – this was a wall of mixed rock and ice which they equipped with fixed ropes so they could carry heavy loads there in safety. The weather was horrible – they knew it would be, going in, but nothing had prepared them for just how awful it would actually be. Terray said that it was a monumental struggle to keep hope alive enough to want to continue.

They focused on getting Camp Three, their highest, well-stocked for a summit bid. Three of them were there, waiting for a break in the weather, when an exceptionally bad storm hit, keeping them pinned down for 5 days. Melting snow for water to use in cooking and drinking is all-important in a place like that, and just as they were about to run out of fuel for their stoves, a lull allowed them to retreat down to Base Camp. Even there, at 2,625 feet, the storm raged for 2 more days and it snowed right down to that camp.

On the third day at Base Camp, the weather suddenly cleared and was fine. Same thing the next morning, so they knew they had to go for it. In high spirits, they took turns breaking trail through waist-deep snow all the way back up to Camp Three that same day. Above this high camp rose a vertical wall of 2,500 feet. The next day dawned, bitterly cold and the weather threatening. No matter, they knew they had to try. They found the climbing extremely difficult, and by seven o’clock that evening they had only climbed 400 feet on the wall. They stuck to their plan, and fixed ropes as they descended back to high camp so as to speed up re-climbing that part.

Miraculously, the next day dawned clear and calm. They took lots of pitons and little food and water, and only a down jacket for the bivouac. Even with the fixed ropes, it took them 4 hours to reach their high point from the previous day. After that, things became even more extreme, requiring a lot of aid climbing. On the worst stretch, one pitch took 5 hours to complete. By nightfall, they had climbed half of the face, and were forced to spend the night on a narrow, outward-sloping ledge, suffering from lack of clothing and food.

The next day, the technical difficulties eased up, but there was more ice on the rock and they were forced to climb in crampons. They were faced with difficult route-finding, and the weather started to look threatening again. Getting pinned down in such a spot in a bad storm could easily spell death from starvation and cold. That fear made Terray want to turn back, but Magnone was determined to forge ahead and they did. They had run out of pitons when the difficulties finally lessened and they reached the summit at 4:00 PM. The weather was closing in fast, so they lost no time in starting back down. They described their descent as a rout – it took 18 rappels to reach the top of their fixed rope, where the storm came on with a vengeance. At ten in the evening, they fell exhausted into the arms of their friends at Camp Three.

Lional Terray is the only human who has made the first ascent of two of the world’s great 8,000-meter peaks, Annapurna and Makalu. He describes Fitzroy as the peak on which he most nearly approached his physical and moral limits. The remoteness from help, the incessant bad weather, the verglas with which it is plastered and the terrible winds make climbing on it mortally dangerous.

On the walk out, we had this view north up the Río Cañadon de los Toros. A dirt road runs up this valley for about 20 miles from El Chaltén and ends in a forested campground by a lake.

Speaking of lakes, here is Lago Capri, a well-known spot along the path – it is also known as Laguna del Pato

Here is a view of the peaks immediately to the north of Fitzroy itself.

As we were walking out to the village, we had this enticing view of the top of Fitzroy.

A bit farther on, we had this much more open view of the Fitzroy group. The view is to the west, and the peaks we are seeing, from L to R, are as follows: Aiguille Saint Exupery; Aiguille Rafael (tiny); Aiguille Poincenot; Cerro Fitzroy; Aiguille Mermot; Aiguille Guillaismet. It was remarkable to have such a clear view.

Once we arrived at the village, there was a one-hour wait for the bus to arrive. I already had my return ticket so I was okay, but the bus was full, nary an empty seat. Soon after we started out down the dirt road back to civilization, the driver stopped the bus and announced that we should all get out. He informed us that during the summer tourist season, he made the long round-trip drive 7 days a week from El Calafate, with never a day off. He went on to say that today was the first time in an entire month that the mountains were this free of clouds, and that we should count ourselves among the very lucky few who would ever see such a view. The clicking of shutters was non-stop. This was the best photo I could take, long before the days of digital photography.

Cerro Torre is the impossibly steep spire on the left. Its first ascent wasn’t made until 1974. Here’s a link to a Wikipedia site which has some good history and photos. I was really grateful for this glimpse of it, from a distance of only 10 miles. The driver was really pleased that he could afford us this opportunity and he let us take our time as he had a smoke by the roadside – his courtesy earned him some extra tips once back in town. The bus ride seemed endless, and it was 8:30 PM by the time we arrived back in El Calafate. I stopped in at the Pinguino bus company office and learned that they did have a reserved seat for me on the two segments of the trip to Río Turbio. I was relieved, both figuratively and literally, as they collected $26.50 for the long trip. I then bought some groceries and headed back to the hostel, where I found a big, noisy group from Santa Fé.

I waited for the owners to arrive, but they never did. While waiting, I showered and put on a set of clean clothes. Someone hunted down the owner’s son for me – I gave him back the rented sleeping bag, and he gave me back my passport (back in the day, it was customary in Argentina for a hotelier to hold your passport while you were their guest). Another thing – I had reserved a bed for the night before I left for Fitzroy, and they had screwed up and given it away. They felt badly about it, so they made a quick phone call to the Hotel de la Loma to see if they could accommodate me there. The word was “yes” and by the time I walked over there, it was midnight. They were very courteous, and as a way of helping fix the mess their friends had caused, they gave me a $33.00 room for only $8.00. No question, it was the best room I’d had on the entire trip. It was so damn late by the time I got to sleep, but just a normal time for Argentines.

This chapter of my trip was now over, but it had turned out to be a complete success. Would I have such good luck on the next stage, where I would cross into Chile? It’d all become quite clear tomorrow.

Please stay tuned for the next installment of this story, Part 13.

Please visit our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690