I just came back from an amazing 4 days in what has now become one of my favorite Arizona ranges. In case you haven’t guessed it, I’m talking about the Tank Mountains.

I got off work early, and headed out on a Wednesday just after noon on a fine February day. In my part of the world, the Sonoran Desert, February means 70-degree temperatures and sunny, blue-sky days. Meanwhile, much of the rest of the country was scraping ice off their windshields and shoveling their driveways. 150 miles later, I turned north off Interstate 8 and headed into the hinterland. This area is about half-way between Tucson and Yuma, and about 60 air miles north of Mexico. If undocumented border-crossers haven’t been picked up by their accomplices by the time they reach I-8, there’s no point going any farther – they’d never make it the extra 50 miles north to I-10, and besides, there’d be nobody there waiting for them. The result of that fact is that if you’re climbing north of Interstate 8, the area is free of Bad Guys and their trash, and that is a lot less to worry about.

Four hours after leaving home, with a lot of back-roads driving under my belt, I arrived at a spot that would serve well as a campsite for my first night. Near Snyders Well sat Peak 1065. One previous climber had stood on its top, a bit more than 2 years earlier. On the summit, a cool breeze was blowing, and I beat a hasty retreat. Only an hour for the round trip. Here’s the view of its west side from the nearby desert floor.

It was a chilly night, near freezing, and it was hard to crawl out of the sleeping bag the next morning. By 7:00 AM, I was fed, packed and rolling north. There were no issues, and an hour later I had covered a lot of ground. As I drove, I passed some old friends, like this one, Peak 1656.

And this guy, Peak 1908.

As I rounded “Pillar Peak”, I saw these huge rocks which had fallen down from its north side. This one was as big as a house.

Others, the size of a room, were almost blocking the road – notice I said “almost”. This stretch of road makes me plenty nervous – if another one came down, it’d crush a truck like an egg. All it will take is one more big rock to fall in this narrow spot and the road will be closed forever. There is never any maintenance on these roads.With a little stealth driving, I found myself parked a while later at an amazing spot in a remote rocky wash.

This would be my starting point for the first peak of the day, at almost 9:00 AM. As I set out, I was surrounded by stunning desert scenery like this – it never gets old.

As I rounded a corner, I had this first view of my peak. This was Tanker Benchmark, elevation 2,152 feet.

It would be a thousand-foot climb, and I was really looking forward to it – in fact, had been for years. Missed opportunities, but I was making up for lost time. As you can see from the above photo, the peak was well-defended. Cliffs girdled almost all of its east side, but there looked to be one weakness near the north end. As I climbed higher, here’s what I saw – a break in the ridge, where the shadow meets the sunshine. That would only leave another 200 feet to the summit.

There were plenty of good rock formations on the way up.

The break on the ridge worked – a few class 3 moves, and I was on easy ground. A look back down the ridge to the north offered a front-row view over nearby Point 2052, a sizable outlier of Tanker. There I stood on Tanker Benchmark, elevation 2,152 feet.

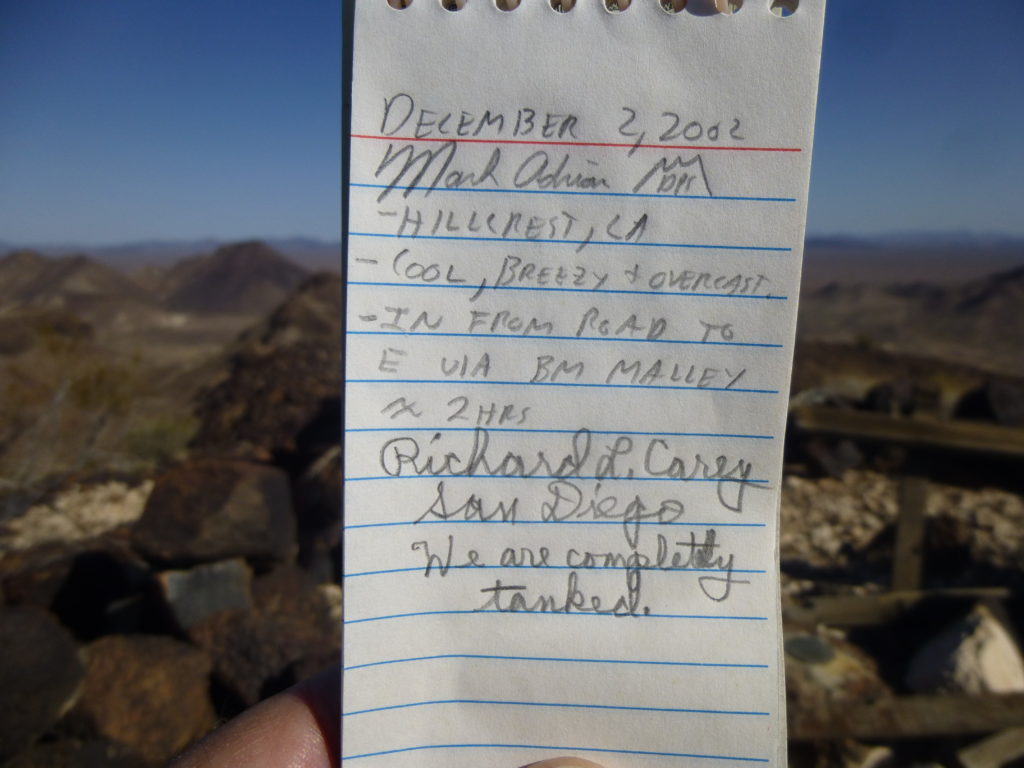

On the summit, inside a cairn, was a register left by Richard Carey. Rich is famous for his registers. Check out the next photo and you’ll see what I mean. A glass jar with pencil and paper sits inside nesting cans which have been painted with a rugged exterior paint. His last longer than any others.

Rich and Mark placed the register back in 2002, so it had weathered 15 years of extreme desert heat, yet aside from a little windblown dirt it was as good as new. Here is what their entry said.

One other climber, Phoenix resident Bob Moore, had climbed the peak back in 1987, so Mark and Rich made 3, and then the old Desert Mountaineer made 4. The benchmark was easy to find.

It had taken me 1 hour and 15 minutes from my vehicle to the summit. I spent a while on top, soaking up the amazing views. This was an important climb for me, capping off a list of peaks in the eastern Tank Mountains. If you’re not a peakbagger, this climb may not seem like a big deal, but it is. Any guesses as to why? Since the original surveyors were there in 1964, only 4 climbers have stood on top of it. Part of the reason might be that you’re not supposed to be there – it’s a stealth climb. It’s a big, brooding peak – well-defended, very attractive, visible from as far away as places like Mt. Union near Prescott, a full 115 air miles away.

Half an hour later, I started back down the way I’d climbed up, at least on the higher part of the mountain. It’s always nice to pick a different route to return to your vehicle, and I could do that lower down. I chose to descend a wash that may not have seen another human since early Native American people occupied the area. There, I found a series of natural water catchments in the solid rock (the proper name for these in this part of the world is the Spanish word tinajas). Depending on their depth and how much shade they get, these may hold water for weeks or even months to slake the thirst of creatures living in the area. No humans would benefit from this water, as none pass through the area on foot. All indocumentados have given up 25 miles earlier, to the south at Interstate 8. You won’t find any of their leavings up here, not a one.

The route I was traveling was so unique – long stretches of rocky drainage, like this one.

Before I turned a corner and lost the view, there was this last look back.

It was almost noon by the time I reached my truck. It only took a few minutes to change out of my climbing duds and have some lunch, then start to my next objective. A spot had intrigued me for years, and I wanted to explore a bit. The rock outcrop there was fascinating and made for some good photo ops.

All good things must end, and my time there was one of those things – I drove away and headed to my last project of the day. By the time I’d parked and gotten ready, it was already 1:30 PM. Here’s what I had to do before the day was out. There was something I’d first seen 2 months earlier on my trip in here with Luke. He and I had talked about it, wondered about it and even tossed around the idea of climbing it, but circumstances didn’t allow it. So here I was, back again, and exploring it was a top priority.

When we first saw it, we couldn’t help but notice how flat it was – flatter even than most of our usual flat-topped buttes or mesas. If you click on this link, you will then be looking at a topographic map of this feature. You’ll easily see how flat it is. Here’s an actual photo of it taken from a few miles away.

Seen from above, it resembles a gigantic tooth. The part to the west would be the crown, and the two long parts pointing to the east would be the roots. It is so flat that, from one end to the other, it rises a mere 200 feet. Luke and I had seen it from several angles, and it was always quite striking. He even joked that it would make a good landing-pad for UFOs.

Setting out on foot at 1:30 PM, I headed cross-country towards The Tooth. It was a fine day – cool and breezy with a clear-blue sky. My truck was parked in a prominent spot, one where it could be seen from afar. One of the first things to happen was crossing a big wash. It had no name, but it was major – the valley it had eroded over time into the desert floor was a full 900 feet wide. Remember the wash I was in earlier in the day for Tanker, the one with so much rock in its bed? This was the same wash again, just a few miles farther downstream. Earlier, once down from Tanker, it had been tempting to simply continue down the wash to reach The Tooth. This was one of those situations where 2 climbers with 2 vehicles could have had some fun with this. Start at one vehicle, finish at the other, then drive back around to pick up the first.

Once beyond the wash, I continued across very flat desert. Passing between 2 small hills, I was now approaching the northeast corner of The Tooth.

An easy scramble up some good rock and there I stood on the flat part of The Tooth, or at least the edge of it. Here’s what I saw.

I’d been curious as to what I’d find up there, and now I knew – cactus, ocotillo, a few scruffy bushes and about a billion volcanic rocks covering the ground. You need to watch every footstep on ground like that – it’s so easy to step on one of the rocks and twist an ankle or fall on your face. I guess the rocky surface would make for a rough landing for UFOs after all – sorry, Luke!

For some reason, before I visited The Tooth I thought its northwest corner would be the highest point. After all, there were 2 separate places with closed 1500-foot contours, one on the northwest corner and one on the southwest corner. The former enclosed a much larger area, so it might be a reasonable guess that within its boundary it reached higher into the sky. I made a beeline for the northwest, but soon realized that it was not the highest point on The Tooth. The other corner rose up more steeply, and was clearly higher.

It had been my goal to circumambulate the entire perimeter of this strange uplift anyway, so visiting both corners wouldn’t take me one bit out of my way. When I strolled on to the southwest corner and had a good look around, there was no doubt at all I was on the highest point. Although technically The Tooth was no peak by any definition we peakbaggers use here in Arizona, it was a special feature in its own right, so I had brought a register with me and filled it out. Burying it within a cairn I constructed, I ate some lunch and savored the view – it was 3:00 PM. This is an exceptionally scenic part of the Tank Mountains, and I felt very fortunate to be there.

I had now walked along 2 complete sides of The Tooth, its north and west. As I left the high point, my plan was to walk along the southern root, along its length from west to east.

This root was quite narrow, as little as 200 feet wide, and as I went it struck me that there was an obvious canyon separating the two roots.

As I walked, this canyon was on my left (north) side, and to my right (south) side, the land dropped steeply down to the desert floor 400 feet below. Much of the canyon walls were rugged, like this.

I didn’t know what I’d find at the end of the root, but the map told me that it did pinch out. Hopefully there’d be an easy way down and off of it. It didn’t take long to reach it, and I spotted a way down into the canyon below.

Another odd feature of The Tooth was a large fragment that sat, detached, from the northern root – it was plain to see as I stood at the end of the root. It was an odd structure, 1,600 feet across.

I dropped down to the canyon bottom, where I crossed over to the other side and started up the steep, loose slope towards a notch.

This went well, but the hillside forced me to crawl beneath a tree with sharp spines. For a moment I was stuck, as its branches held me fast, but I pushed hard and broke free, to the sound of a loud tear as my fleece jacket ripped. This happened just below the obvious white patch on the cliff near the blue sky in the above photo.No matter, I was through, and soon stood in the notch. I’d been hoping that there’d be no problems when I got there, and I got lucky – the way down into the next canyon was straightforward. A bright scar on a cliff was evidence of a recent rock slide.

From the saddle, it was easy to see how well-guarded the fragment was.

This last canyon spat me out on to flatter desert, where it was a straightforward walk back to my truck. I had spent 3 happy hours exploring The Tooth, glad of the effort – a sort of a mini-bucket-list project.

My trip wasn’t over – I spent 2 more really enjoyable days in the area. The rest of the climbing went well, but there was one scary incident I experienced the following day that I thought I’d share with you. Over near Baragan Mountain, I had to drive across a wide wash to reach a couple of peaks. Hours later, climbs done, I drove back to the wash to cross it and get back out to the main road. Every time I tried to drive up an embankment to escape the wash, where ATVs had previously driven, I found it too soft – it would collapse under the weight of my truck. More than once, as I tried backing away from the bank, my wheels would dig themselves in. Even in 4WD, it was a close call – I always carry a short-handled shovel in the truck in case I need to dig myself out of trouble, and I thought I’d be using it that day. In several different spots, my attempts to climb the bank failed where others had driven before me in ATVs. I finally decided that instead of fighting it, I’d just drive up the wash, staying in its main channel. Even then, the sand and gravel in the wash was treacherous, trying continually to suck my wheels down. There were several spots where the sand slowed me to a crawl and I despaired of being stuck. Finally, miles later, Red Raven Wash released its hold on me when I reached a road which crossed it and allowed an escape. It’s a sobering thought, the idea of being axle-deep in soft sand, unable to extricate yourself and no help within many miles. Fortunately, that was not my fate this time around.

So ends my tale of Tanker and The Tooth. Thanks for accompanying me on another desert adventure.