It was just a name, one of many that peppered our topographic maps out here in the desert. I knew nothing of its meaning, just that it had been given to a large peak in the southwestern part of Arizona. It seemed worthy of a look, so away I went. My timing was interesting, to say the least. The remnants of Hurricane Rosa had swept across the state, dumping record amounts of rainfall – so much water had flowed in places that rarely saw any that some roads and watercourses were forever changed.

On a sunny Sunday afternoon, I drove to the base of the peak. I had traveled some miles west on a route known to locals as Rocky Point Road, passing through miles of irrigated cropland to arrive at the road’s namesake feature. Rocky Point was a nondescript bump at the southern end of the mountain – you had to drive around it to get to the road that climbed to the top of the peak.

Since getting to the top of Oatman Mountain was my goal, I soon found myself face-to-face with a sturdy metal gate. There was no driving past that, so I parked and set out on foot.

It was an easy walk up the decent road to gain the 1,100 vertical feet to the summit, which bristled with all manner of communication towers.

A curiosity sat close by the climbing register. Hang-glider pilots had constructed a concrete ramp for their takeoffs. They had more nerve than I. Imagine hurtling yourself off a cliff, on purpose, into a thousand-foot plunge into the abyss!

As I prepared to start back down the road, thunder rumbling nearby, a glint of something in the valley below caught my eye. Could it actually be what it seemed – water flowing in the channel of the Gila River? See it in the center of the photo? Hmmm, I needed to investigate further.

Once back down at my truck, I drove a few dusty roads to solve the mystery. Sure thing, a sight I’d never before seen in these here parts, a healthy flow of water in the normally-dry Gila River.

And yet, less than a mile away, the channel was completely dry – the water was being swallowed into the parched earth as quickly as it arrived. I needed to investigate further. Only 9 miles upstream lay the Painted Rock Dam, so away I went on good roads to check things out. I fully expected to see a dam with a reservoir behind it filled with Gila River run-off, so imagine my surprise when I arrived to see road access to the dam completely blocked off. A nearby fenced compound was puzzling, and as I stood there scratching my head a young man exited a building and walked over. His name was Will, and he was a wealth of information. He told me that the United States Army Corps of Engineers had built and now maintains the dam. The topographic map showing a boat ramp and campground was years out-of-date, as none of that existed any more. The dam sat a full mile away, and all I could see was its flat top.

When I told Will that farther downstream I’d seen water flowing in the river channel, he quickly informed me that it was not Gila River water, as nothing was flowing from the dam. It had to be water from other tributaries lower down, such as Woolsey Wash, Fourth of July Wash, Yellow Medicine Wash and Loudermilk Wash. He directed me to this website to learn more about the dam and its history. I thanked him and moved on. By the way, the Gila River is the only one that crosses the entire state of Arizona. It enters from New Mexico in the east, and flows west all the way to Yuma where it empties into the Colorado River, traveling 649 miles in the process.

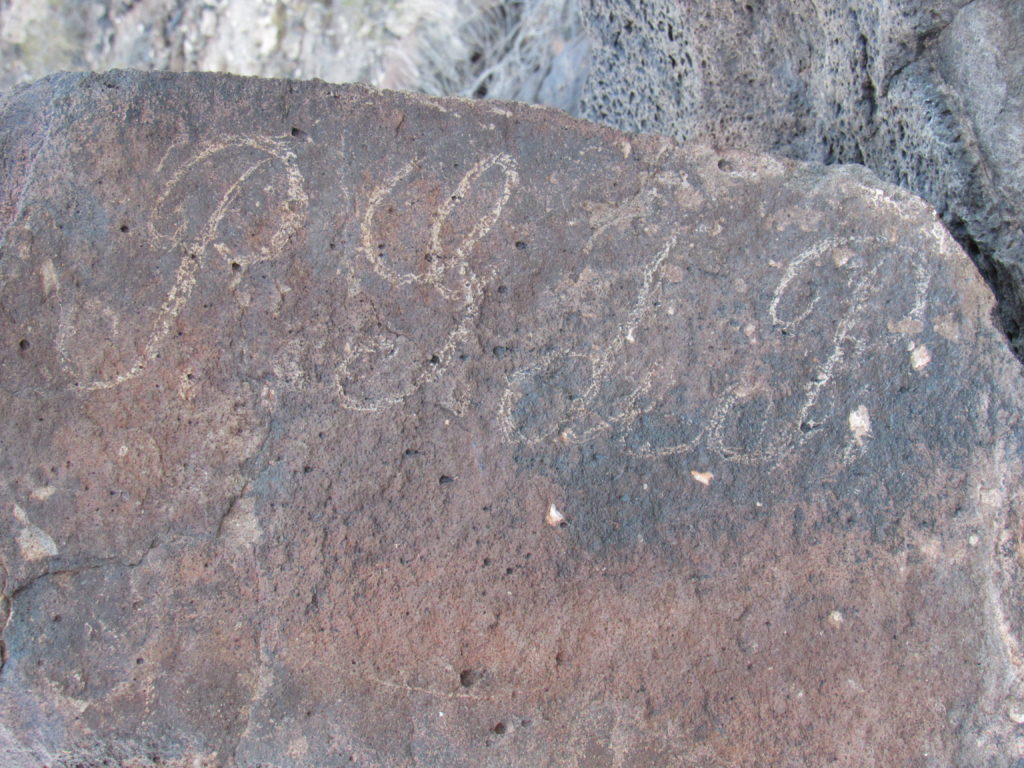

But what about the name of Oatman and the history of this area? I was curious to delve deeper. A few miles away sits the Painted Rock Petroglyph Site, so I stopped in for a look around. If you like petroglyphs, this spot is a must-see. Native peoples have lived in this area for almost 10,000 years. Some of the markings they have left are of the Western Archaic style and are over 2,000 years old.

Even early Anglo pioneers passing through left their own inscriptions.

In my 30-plus years in the desert, I’ve seen many petroglyph sites, but nothing to compare with the 800 drawings squeezed into this small spot. There’s little wonder they protected it.

The Native Americans weren’t the only ones to pass through this area. In the fall of the year 1775, Juan Bautista de Anza led a large group of colonists, accompanied by priests, uniformed soldiers with their wives and children and over 1,000 head of livestock in a long, dusty procession. He was the captain of the Spanish crown’s Royal Presidio at Tucson. Native American interpreters accompanied the expedition, as they would be passing through so many tribal territories. So where were they going? Their trail stretched from Sinaloa and Sonora to Alta California, a distance of over 1,000 miles. They were trying to open a successful land route to the new missions, presidios and settlements being established there. A few miles away from the Painted Rock site can be found a large rock with initials inscribed on it. The lettering is of a style that was used at that time by Spanish-speakers and may be from the time of De Anza.

Another entity that used this route was the Overland Mail Company. It was in business from 1858 to 1861, and their “Butterfield Trail” from Missouri to California ran right through here. Their 3,000-mile route involved 140 stops, each one providing fresh mules, water and a few minutes to stretch your legs. In each coach were crammed 9 passengers, cheek to jowl on 3 benches. There was little legroom, and the seats swayed and made many passengers feel seasick. Imagine enduring this for the 23-day journey from St. Louis to San Francisco, traveling day and night. John Butterfield had 4 rules plainly posted for those who chose to travel on his coaches: don’t drink unless you share the bottle; no spitting into the wind; leave your valuables behind; there is an extra charge for food. As difficult as must have been this epic journey, he showed that transcontinental travel was possible in the American West.

Another group that passed through here and played a part in the history of the area was the Mormon Battalion – here’s their story. In 1846, the United States and Mexico were at war. Anxious to secure California from Spanish control, President James Polk asked General Stephen Watts Kearney to enlist 500 Mormon men for a period of 12 months to assist in the anticipated conflict. Five companies of 100 men each were recruited in Iowa. By the time they reached Santa Fe, their number had dwindled to 340. From Santa Fe to San Diego along the Southern Trail, the Battalion was faced with the lack of a passable wagon road and severe shortages of food, water and forage for the livestock. To overcome these problems, wagon trails and water holes were constructed, and food and water were rationed. Valuable assistance came from the indigenous people living in villages in a few places along the way, who were able to provide an occasional place to rest, some water and trade food for beads, cloth and other goods. The Mormons’ reward for their military service was pay, military standard issue and free passage to the western lands, placing them closer to their desired destination of Salt Lake City.

My friend Dave Jurasevich had recently visited the area and had told me of some other must-see spots, so one by one I searched them out. The first was the gravesite of some children of a pioneering family in the area. Have a look at this idyllic spot beneath the trees.

A broken headstone still stands, testimony to young lives lived here.

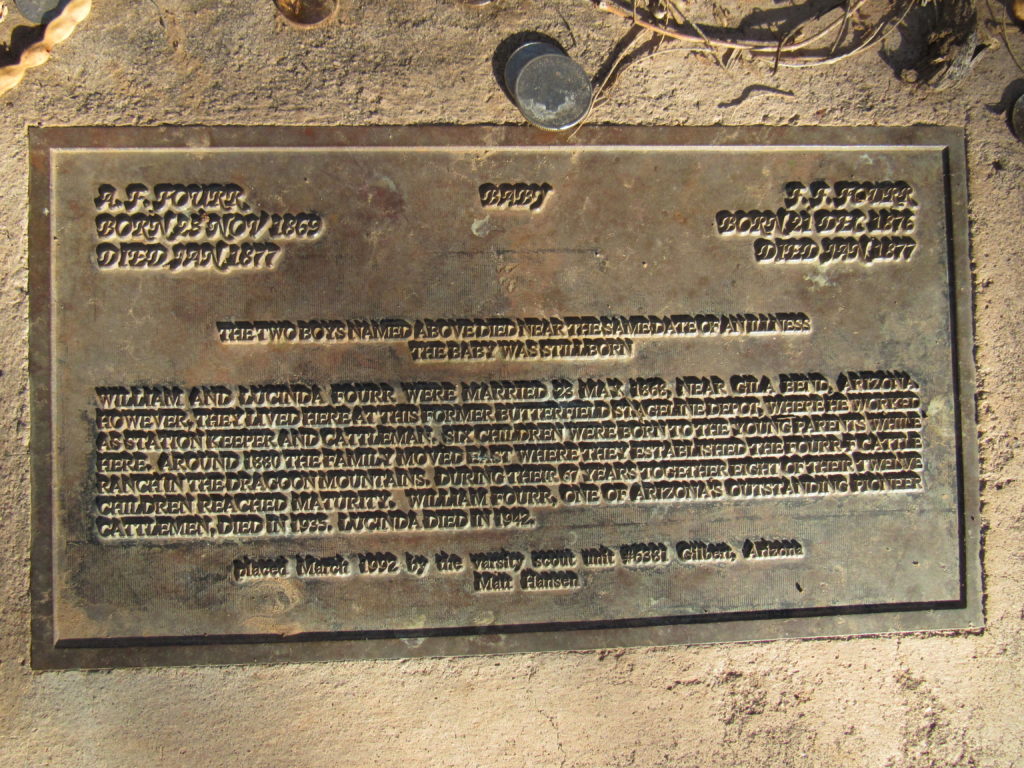

And then there’s the bronze plaque.

It may be hard to read, so I’ve transcribed it here for your easier reading.

A. F. Fourr Born 23 November, 1869 Died January 1877

F. F. Fourr Born 21 December 1876 Died January 1877

Baby

The two boys named above died near the same date of an illness. The baby was stillborn.

William and Lucinda Fourr were married 23 May, 1868 near Gila Bend, Arizona. However they lived here at this former Butterfield Stageline depot where he worked as station keeper and cattleman. Six children were born to the young parents while here. Around 1880 the family moved east where they established the Fourr F cattle ranch in the Dragoon Mountains. During their 67 years together eight of their twelve children reached maturity. William Fourr, one of Arizona’s outstanding pioneer cattlemen, died in 1935. Lucinda died in 1942.

Placed March 1992 by the Varsity Scout Unit #6381 Gilbert, Arizona. Matt Hansen

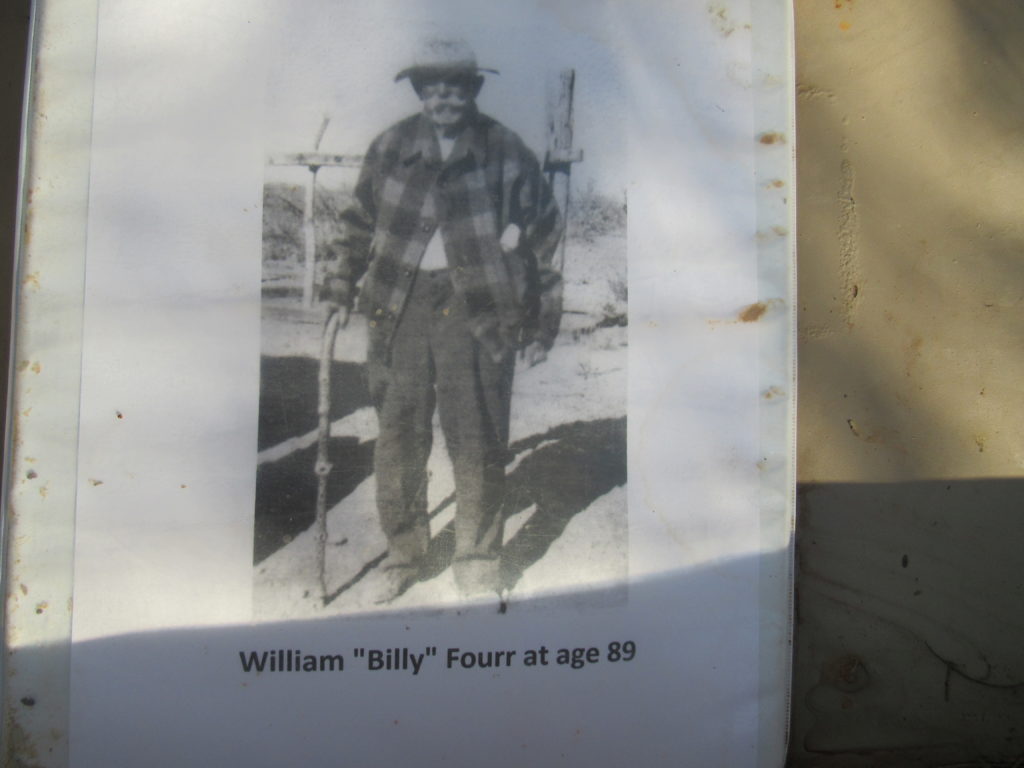

And here’s a photo of William Fourr taken when he was 89 years of age.

Dave also turned me on to another historic site a few miles away, one known only to a few historians. There, in a rocky wash where can be found natural tinajas, sit more petroglyphs. Look at this ancient beauty. The human figure is holding an atlatl.

And this one, which is much more recent.

Thanks to Dave for letting me use these last 2 photos.

Okay, I’ve saved the best for last. Remember how back at the beginning of this piece I’d wondered about the name Oatman? What was its significance? Well, fortunately history has provided us with the answers, and it goes something like this.

In 1851, the Oatman family was traveling west. The parents and their 7 children, along with animals and a covered wagon containing all of their worldly supplies, were attacked by a group of Yavapai Indians above the bank of the Gila River. The father, the mother (who was 9 months pregnant) and 4 of the children were brutally clubbed to death. Their 15-year-old son was clubbed and left for dead, his body thrown over a cliff. The Indians made off with 2 of the girls (Olive, age 14, and Mary Ann, age 7) – they were taken to be slaves. After a year of brutal treatment, they were traded to a band of Mohave Indians who treated them with kindness. During the 4 years Olive lived with the Mohave, her younger sister died of starvation. Olive was tattooed with blue facial marks in the fashion of the tribe. Five years after her initial capture, the commander of Fort Yuma arranged to buy her freedom from the Mohave. Much has been written about the life of Olive Oatman – one fascinating book I strongly recommend is “The Blue Tattoo” by Margot Mifflin.

Which brings us back to my present situation. Late in the afternoon, I arrived at a lonely spot overlooking the Gila River. There, I found this marker.

It was a sobering moment, standing in the very spot where the Oatman family had been brutally killed. A few feet away was the top of the track that was used by travelers such as the Oatmans to climb from the Gila River floodplain up to the top of the mesa where they were killed. Here is a photo of the exact track, looking down. Over to the right can be seen a bit of the cliff over which the Oatman boy was thrown after being bludgeoned (amazingly, he survived). The flat area down below on the left is known as Oatman Flat.

A few feet away from the Oatman massacre sign is this marker, located at the top of the track.

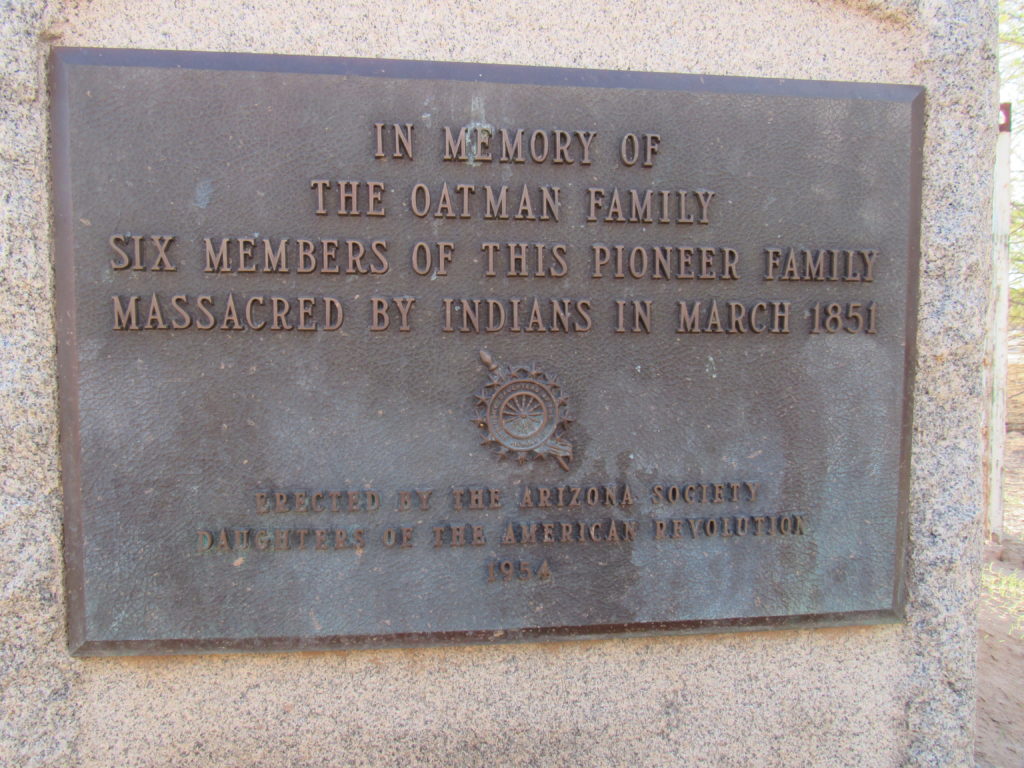

I drove around and down to Oatman Flat, where I visited this memorial to the Oatman family. It is in an isolated spot, and if you didn’t have specific information as to how to find it, you’d never know where it is.

Here’s what the plaque says:

This memorial is very close to the actual massacre site, down at the bottom of the mesa and half a mile away.

Well, my visit to the Oatman Mountain area had certainly turned out to be more than just a simple climb. So much interesting history! As I drove away, crossing Oatman Flat to leave the area, something caught my eye over in a field. I drove over to have a look-see, and found 3 old vehicles. Here they are (thanks to my brother-in-law Lee for his identification of these).

I love finding old vehicles such as these, and it seemed a perfect finish to a trip that delved into events of long ago.