There’s a mountain range in Southwestern Arizona, a pretty area between the Kofa Mountains on the west and the Eagletail Mountains on the east. It sits about 40 miles east of the Colorado River, boasting 30 or so peaks of its own – fewer than some other Arizona ranges, but more than most. Historical records indicate that the Little Horn Mountains are “so called because they are smaller than the Big Horn range to the northeast”. I guess it depends on how you define “smaller” – both ranges span about the same distance from end to end, but the Big Horns have only half the number of peaks; also, the range high point of the Bigs is only 132 feet higher than the Littles.

In any case, it had been 30 years since I had last visited the Little Horns. Yes, in the intervening years I had seen them from afar, from the Tank Mountains to the south, and wondered how it would be to explore them in detail, but that’s as far as my interest had gone. They had been pretty-well picked over by strong peakbaggers such as Bob Martin, Barbara Lilley and Gordon McLeod back in the 80s and 90s, and further explored by the likes of Andy Bates and Mark Nichols in more recent years. Still, I felt attracted to them, and in early 2019 I succumbed to their lure, deciding to spend some time getting to know them better.

The 2 easiest ways into the range are from Interstate 8 to the south, leaving from Dateland, or from Interstate 10 to the north. I chose the latter. It was around 200 miles from Tucson to the Vicksburg Road exit, about 3 1/2 hours of driving. Another hour of dirt roads took me to where I could check out access to some peaks for the next day. On the way in, I passed the very impressive Coyote Peak. It’s a fact that a lot of coyotes live in Arizona, and residents have used the name “coyote” on no less than 127 different features in the state. A dozen of them are mountains, so Coyote Peak is expected – in fact, there are 3 different peaks with that exact same name. This one may be the most impressive, though.

Coyote Peak isn’t a part of the Little Horn Mountains, though – it sits out by itself on the Ranegras Plain, and if it is to be assigned to any mountain range, it should be a part of the New Water Mountains if anything. I carried on and soon reached a spot where a faint track marked as 4WD headed west into the hills. I followed it more than 2 miles over hill and dale to where it ended in a basin, a perfect spot to start climbing the next day. Back out I went to the main road by a different route, satisfied that I had things well in hand. I made a quick climb of nearby Peak 2051 in the waning hours of the afternoon, my first foray back into the Little Horn Mountains – the game was afoot. Five others had been there before me.

It didn’t take long to find a good camping spot, but it was too cold to cook. I sat in the cab of my truck, engine running and heater on while I munched cold food. It was a chilly 44 degrees F when I turned in, but that was balmy compared to the 24-degree temperature that greeted me the next morning. The water bottle beside my sleeping bag was frozen. After a late start, I drove back up the rough road I’d discovered yesterday. While I drove through a tight spot, my right side lurched down into a deep hole hidden from view. The truck wouldn’t move, even in my lowest gear in 4WD – I was stuck! I got out and had a look. Goddamit – not good. My left rear wheel was way up in the air, the right rear was sunk into a deep hole. Here’s what I saw.

To make things worse, the entire right side of the truck was plastered hard up against a row of spiny brush. Well, I won’t belabor the point, but suffice it to say that I had to employ my best engineering practices to get out of this mess, nothing that an hour of hard work didn’t fix. By the time I reached the end of the road and was setting out on foot, it was the late hour of 9:15 AM. From near where I parked, here’s a view ahead to where I had to go to get my first peak, which is on the skyline off to the left.

I wasn’t sure what to expect when I reached the top of Peak 2352, but I found a register with 4 prior entries. The day was young, and my plans included another peak farther west. I followed a series of ridges to a valley bottom, where I had this look at it.

By mid-day, I stood atop Peak 2315, where only one had stood before – my friend Andy Bates, 4 years earlier. At the base of this peak I found an old road, not shown on any map, no doubt left over from an earlier time when mining activity was more prevalent in the Little Horns – you can see it in the above photo. From atop Peak 2315, I had this look back to my first peak of the day.

A look back east to the first one of the day. It is the long ridge on the skyline on the left side of the photo.

In order to return to my truck, it was necessary to pass right by the first peak of the day. To mix things up a bit, I decided to follow a canyon back to it, not the ridge route I’d used to get from the first peak to the second. As long as you know where you are at all times, you can afford to do this, but you’d better stay sharp – the moment you lose track of your exact location is when you’re going to get into trouble. It was almost two o’clock by the time I stood looking down to my truck.

As I walked back down the final slope, I passed an old mine shaft. Miners had spent considerable time here in the past, and someone had hastily covered the top of the shaft with plywood to make it a bit harder to accidentally fall in.

Once I’d regained my truck, I drove back down the valley’s rough roads, making sure to give the hole that had trapped me this morning a wide berth. It was now time to move to a different area. I traveled a series of ever-worsening roads to end up at a remote spot where I stopped for the day, right where the last bit of faint road ended. This was a great spot, surrounded by imposing peaks. The truck was parked on top of a rise, visible for a long way in every direction, good for finding my way back. I was surprised to find that my cell phone had good reception way out here. The world seems to have shrunk – you can now be in a place that requires a lot of hard work to reach on foot, and yet your cell phone leaps across the gap effortlessly to put you in touch with anyone on the planet.

The next morning greeted me with 28 degrees and a perfect sunrise.

After oatmeal, I set out on foot eastward up a long valley – the day was fine, the going was easy, and I had all the time in the world. When at last I reached the head of the valley, I dropped down into another drainage, still heading east. My peak was visible in the distance – parts of it looked well-guarded, so only a closer look would reveal the best way up it.

After going beyond the cliffy bits, I picked a slope to climb, then worked my way up a ridge to the summit. Peak 2203 showed no sign whatsoever of anyone having visited it, so I relished the task of building a cairn and leaving a register.

Although this peak wasn’t too impressive, it was surrounded by several that were. To the west was Peak 2810 with its long east-west ridge.

To the north sat the massive Peak 2620, filling up the northeast corner of the range.

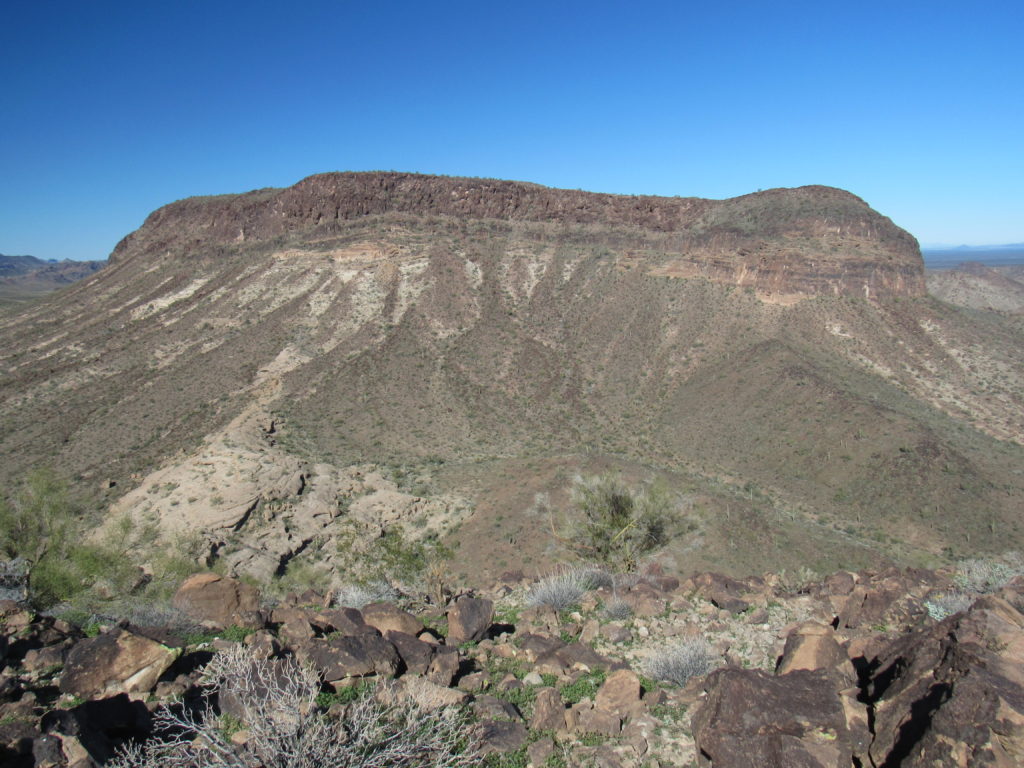

To the south, filling up the entire skyline, loomed Little Horn Benchmark, which I had climbed back on December 6, 1989. Basically a huge, sprawling plateau 5 miles long, it dominates the eastern half of the range. My wide-angle lens only shows half of it in this next photo.

It felt good to finally be on a summit which hadn’t been trodden by others. Relishing the moment, I stayed a full 40 minutes, even managing a phone call home. All good things must end, and an hour after reaching the top, I was back down in the wash at the base of the peak at 11:40 AM. The next hours would be spent enjoying the miles back to my truck, staying in the valley bottom and seeing what I could see. This next photo shows a view up the long valley I must travel to get back to my truck, but it only shows the eastern half of the journey – the western, longer half is not visible at all.

Those of you who don’t live in the desert might not know that the Sonoran Desert is the world’s most vegetated. In places, it’s possible to park a vehicle and not be able to see it a few hundred feet away because of the trees and brush. Since much of our vegetation is sharp and thorny, you want to avoid brushing up against it or ploughing your way through it. This was the case as I made the long walk back to my truck on this fine afternoon. When possible, I walked in the dry wash, but when it would be brush-choked I’d move off to the sides where I could walk more easily. Here’s a look at some of that vegetation.

There were welcome open spots in the wash where outcrop made for easier going.

There were even a few pools of water which would linger after a rain – these are known as tinajas.

At the head of the valley where the drainage changed direction, there stood some interesting cliffs. Once atop them, I ate my lunch and pondered the rest of the trip.

One final look at the impressive Peak 2810 as I neared the truck, which, it turns out, would play an important role in my future climbing in this range.

Six hours after starting out, I arrived back at my truck. These 2 days had shown me that the range had been worked over more than I’d anticipated. I came here thinking that 3 of the 4 peaks I’d climbed would have been untouched, but it turned out that for only one of them had that been the case. That was just fine with me, as I was in good company – all of the previous ascents had been done by friends.

Please stay tuned for the next installment entitled: The Little Horn Mountains: Part 2 – Solitude