To the west of Tucson, Arizona lies an Indian reservation the size of Connecticut. It is a vast land full of amazingly-beautiful peaks, and back in the 1980s I had spent some enjoyable days out there climbing the high points of its mountain ranges. Once that was done, I didn’t think much about climbing there again. Years passed, then something happened to focus my attention on this place, the Tohono O’odham Indian Reservation. Climber friend Andy Bates sat down and carefully pored over the dozens of topographic maps that covered the res and put together an amazing list of 401 peaks situated on that land. He did all of this long before climbers had any of the high-tech tools that exist today, and 20 years later his list still stands as a example of high-quality map sleuthing. When Andy shared this list with his friends, I was impressed by it, but the thought of going back out to the TOIR, as we climbers call it, and climbing more of its peaks, didn’t appeal all that much. Then something else happened which completely changed my mind in that regard.

In early January of 2001, I got a call from another climber friend, Dave Jurasevich, in Los Angeles. Around that time, several of us had decided to work on climbing the highest point of each of the “hills” as shown on the Arizona topographic maps. There were more than 100 of these sets of hills, widely scattered throughout the state, and Dave had decided that climbing the highest point of each of the 11 groups of hills on the TOIR would be a fun challenge. I agreed in a heartbeat to accompany him.

On the morning of January 19th, we met at the Stanfield Road exit on Interstate 8, a quick 85 miles from my home in Tucson. It was a perfect, blue-sky day in the desert, filled with the promise of some fine climbing to come. It only took us half an hour on pavement, then good dirt roads, to park for our first goal of the trip. A wash had eroded the road to the point where it couldn’t be easily driven any farther, so we started walking along it to the west another 0.8 miles. It was then time to head cross-country to the peak itself.

As we walked, I was telling Dave how Dottie and I had recently visited a site where Indian potsherds were common. Archeologists had spent quite a while scouring it and had removed everything of value before construction on a new subdivision was to begin. Even then, small pieces of pottery were easily found lying on the ground. Dave thought that was pretty cool and said he’d like to look for things like that too. No sooner had he said it when I looked down at our feet and spotted a small piece lying out in the open. After examining it, we put it back where we’d found it, both of us realizing that such bits of ancient pottery must be common on Indian land.

In a short while, we’d climbed up to a 1,980′ saddle just west of Peak 2277, then headed west up to a ridge which we followed south all the way to the summit of Indian Benchmark, the high point of the Vaiva Hills. There, at 2,561 feet, we found a rock cairn but no register, so we left one. Neither did we find any evidence of the benchmark. Here’s Dave on the summit.

We returned the same way to our trucks, the climb having taken less than 4 hours round-trip. About 5 miles and 1,150 feet of elevation gain, it was a good start to our little project. Here’s a photo of Peak 2277 – its summit is on the skyline right in the center.

See the dark shadow to the right of the peak? If you drop down to the right of the shadow, you’ll be at the 1,980-foot saddle I mentioned; the ridge we followed to the top of Indian BM is visible behind the 2 saguaros touching the sky on the right side.

In this next photo, Indian BM is the large, bulky mountain filling all of the left skyline in this view looking west.

Here’s a better view of the peak, seen from the south. That is all Indian in the photo.

Hey, that was our first one done, the first of 11, a good start. Dave had figured out an itinerary for the entire trip, and now we were ready to move on to the next one.

Back out to pavement, we drove south on Indian Highway 42, past the village of Vaiva Vo (which means Cocklebur in English), then on south to Kohatk and finally emerged on the major Indian Highway 15 near North Komelik. We made good time continuing south on 15 another 17 miles, taking us to Indian Highway 34. Then we headed west for 7 miles on 34, turning north on a decent dirt road to a corral where we parked for our next peak. We were now in the Chui Tontk Valley.

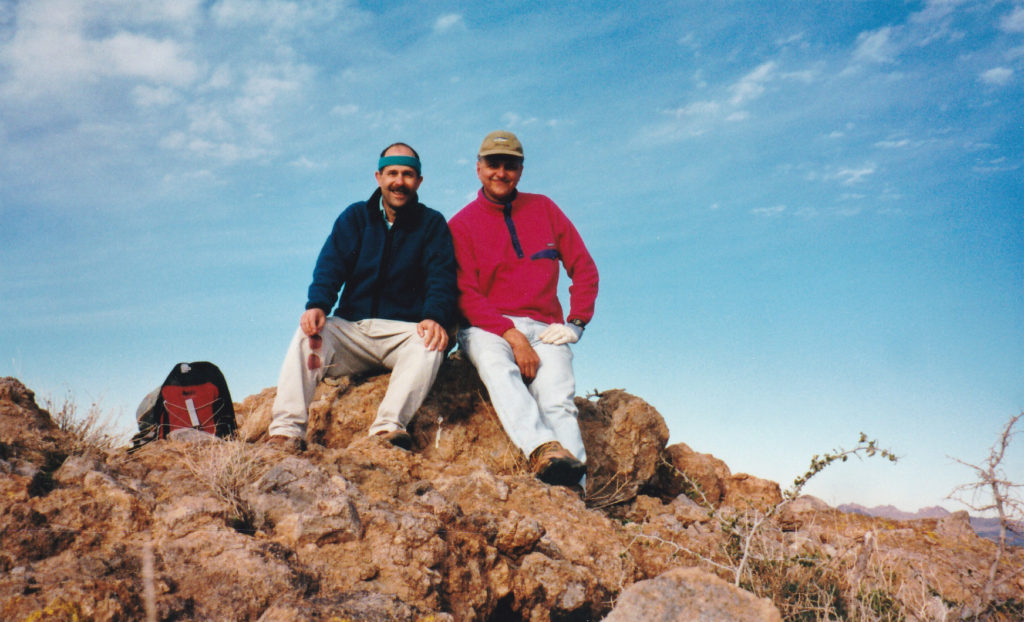

These were the Black Hills, a nice group of peaks sitting just north of the highway. We walked a short distance east, gained a ridge and followed a nice slope to the summit of Peak 2950, the high point. There was no sign of any previous visit, and we left our register in the cairn we built. An easy couple of hours and a thousand feet of climbing took care of this one. Here we are on top. Those are some kind of flying bugs in front of the camera. This made 2 out of 11 completed.

Here’s a picture of the peak as seen from the west side, from near where we started.

I had an odd experience here a couple of years later. It was sunrise of a summer morning, and I’d come back to these hills to climb the other peaks in the group. Close by the highway was a clump of trees by a wash. I’d driven around to the back side of it to park unmolested while I climbed 3 peaks to the north. I was getting my pack ready when, to my shock, a vehicle came around the corner and pulled up to my bumper. A man came out and asked me what the hell I was doing there. I saw the logo on his SUV and knew he was with US Customs (this was in the days before ICE had been created). When I told him I was a climber and showed him my permit from the Hickiwan District on the reservation, he calmed down, told me to be careful and left me alone. Each of us was surprised to see the other.

Dave and I convoyed back out to the highway, then drove farther west to arrive at the village of Ventana. From there, we had several miles of rough driving ahead of us to reach our next peak, and it was along this stretch that our fortunes took a turn for the worse. I was driving my truck, minding my own business, when I happened to glance at the gauges on my dashboard. The battery voltage was lower than it should be, and that meant only one thing, and it was not good – my alternator was failing. We stopped and discussed the situation, but Dave said he had jumper cables and a tow rope, meaning that there was no way I’d be stuck out there. It was evening by the time we arrived at the site of Totopitk. A few people had lived there in the past, but it was now deserted. A lonely spot indeed.

It was a cold, windy evening, no time to stand around admiring the view. We turned in early, feeling pretty good about our first day’s work – 2 down, 9 to go, but I have to say that there was a nagging concern about the welfare of my truck.

Day 2 – Saturday, January 20, 1991

We were moving at daybreak, heading across a couple of miles of flat desert to approach our next objective. This one actually had a name, Cathedral Rock. It was the high point of the Copperosity Hills, and we came at it from a broad ridge on its northwest side. As we neared the top, things steepened. There was a notch to negotiate on the summit ridge, and then we were there. Someone in the past had made a pile of rocks, and we left a register.

The most striking thing about this peak is the absolutely vertical face on its south side. Now, people will talk about a mountain being vertical, but usually it’s an exaggeration. In the case of Cathedral Rock, it happens to be true. I want to show you some pictures to back this up. This first one is taken from the north, showing the start of the face, the eastern edge of it.

Here’s another one, taken from a peak farther east. The lower part of the face is hidden.

The best, I’ve saved for last. Here is a look at the south face. A full 6 contours of 40′ each are just plain gone from the topo map, telling us that the face is about 250 vertical feet tall. Standing on the summit and looking over the edge will put the fear of God into you.

This was by far the most dramatic of the peaks we would climb on the trip. About 4 hours had passed by the time we arrived back at the trucks, having climbed a bit more than 1,000 feet and covered over 5 miles. Nice climb, we felt pretty good about things, but …… my truck – we still had to deal with that. If your alternator is failing, your battery will not charge properly, and if its charge drops low enough, your spark plugs will not fire and your engine will just plain stop. This would not be a good thing. However, if your friend is driving his vehicle along with you, and you have a set of jumper cables, you can recharge your battery from his and then drive more miles. That is what Dave and I decided to do, convoy to the nearest town, a small place called Ajo.

It took quite a while to drive the rough desert roads all the way back to pavement at the village of Ventana, but once done I felt a bit better. From that point on, it was all paved highway. We continued to drive, passing through Vaya Chin, Hickiwan, Why and finally Ajo. My battery actually held out all the way, but I could see the charge dropping steadily. We found the only mechanic in town – I was reluctant to leave my truck there, but had little choice. We unloaded all my gear and threw it into the back of Dave’s truck, a Toyota 4WD like mine, and headed back to the hills – there were a lot more peaks still to climb.

This detour into town had cost us a lot of time and had taken us way out of our path, but it couldn’t be helped. Dave pointed his truck east and drove us almost all the way across the res, most of the way to Tucson. The day was wearing on by the time we turned off on to a lesser road, Indian Route 35, and a few miles later, IR 34. We only drove 6 miles along it before we turned north and drove a succession of ever-worsening dirt roads. I recall we saw a crested caracara sitting on its nest in the arms of a saguaro – very cool indeed. And one more memory lingers of that drive – in the fading light, Dave drove over a fallen saguaro. It didn’t seem like a big deal at the time, but when he was finally back home in Los Angeles he discovered that 2 of his tires had slow leaks from being punctured by long saguaro spines. We were lucky they didn’t both quickly deflate right then and there, as he only had one spare. By the time we called it quits, the road had pretty much faded out and it was dark.

Two days in, and only 3 peaks climbed – down to one vehicle, but still in good spirits.

Please stay tuned for the next installment of this story.