Decades ago, in the Atlantis of my youth, I came up with a cockamamie scheme. I was living in Tucson, Arizona and wanted to climb some high peaks in a mountain range east of town. There were at least 3 of them, and they all shared one thing in common – they were hard to get at. If you attacked any one of them on their own, each would involve thousands of feet of climbing and many miles on trails. The thing is, I had never climbed any of them before and so I thought “what if I did all of them at once?” By doing them all in one big push, I could get them all over and done with on one trip, but it would mean a backpack. Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not a huge fan of backpacking (too much hard work), but I will do it from time to time if it’s the only way to climb a peak. I could say that I almost enjoy it if it’ll get me a whole bunch of peaks, or some especially good ones (such as virgin peaks nobody has done before). So that much, at least, was decided – it would be a backpacking trip, and we’d just getter done.

This trip would take some extra planning, though. If I left a vehicle parked at the finish line, and had someone drop me off where I wanted to start, it should work. So one day, I got on the freeway and drove out east of Tucson, towards Benson. The only thing I knew for sure was that I’d drive around and find a good spot to leave my truck for several days, preferably someplace safe and sort of legal. Well, after driving a series of dirt roads where I kept the truck pointed approximately in the direction of where it made sense to finish my backpacking, I got in pretty close. I passed the Ashrama Ranch and kept going north. The road became a real roller-coaster, but I kept going to the end. I found someone to speak to and told them of my idea of going through the range and could I please park on their property? A Mr. Kardell Winward said it would be just fine by him, that I was welcome to park on his Al Maraha Ranch whenever I wanted and for as long as I needed. Wow, I had really lucked out, and on my first try! Several days later, I was ready to do the deed – I convoyed all the way back out there with a friend and parked by a corral on a hilltop. Back in 1988, I had neither GPS, cell phone nor SOS rescue device. This was back in the days when men were men and we had to rely on ourselves and nobody else. With my truck now safely parked on private property, my buddy drove me back to town, and the stage was set.

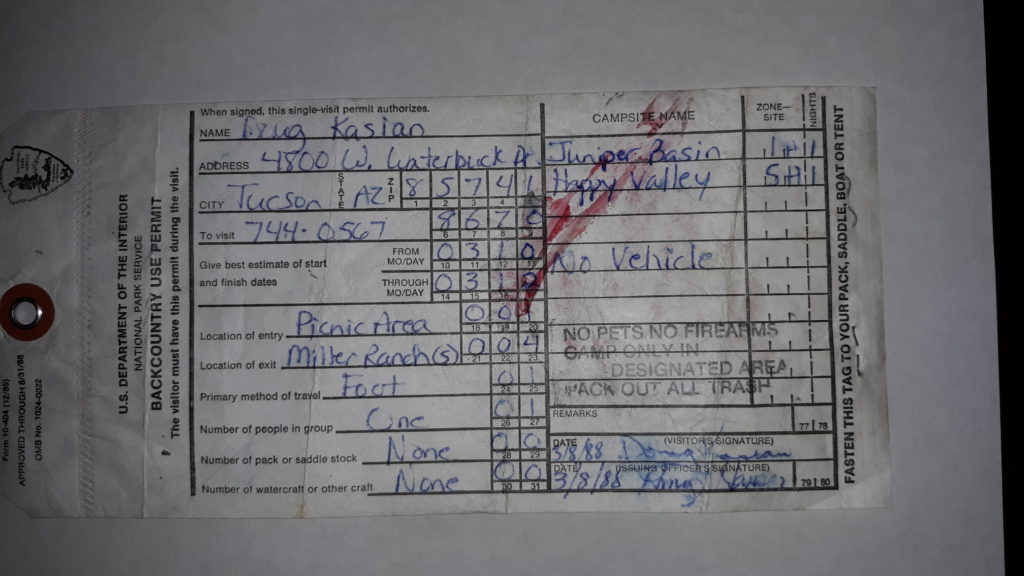

My big day arrived, Thursday, March 10th. Technically, this was winter, but you wouldn’t know it down in the city. I talked a friend into giving me a lift to Saguaro National Monument East. I had driven out there to the visitor center on the 8th to pay for my backcountry use permit, to get that detail out of the way to save time when I’d actually start. I still have the very permit they issued, specifying where I’d camp the 2 nights I’d be out – it cost me a whopping $3.00 total (that was $1.50 per night – it now costs $8.00 per night).

I had to camp in Juniper Basin the first night, and in Happy Valley the second. It states I’d be a party of one, on foot, no pets, no firearms, no vehicle. My friend dropped me off at the trailhead at the Javelina Picnic Area, elevation 3,140 feet, at around three in the afternoon.

The weather was fair as I set out on what was called the Tanque Verde Ridge Trail. This was my first time here, and I didn’t know what to expect, but I was open to anything that came along. The trail headed south through the desert and climbed upwards, in a mile reaching a ridgetop. Nice. A bit of a breeze helped cool me off. My pack wasn’t too heavy, actually lighter than I thought it’d be. I wasn’t carrying a tent, relying instead on a bivi bag, as the prediction was for no rain. Now that I was on the ridge proper, I was looking forward to staying on it for many miles. I like ridges – the views are great, you have a better chance of a cooling breeze and it’s easier to see where you’re going to help plan your route.

I hit the ridge crest at 3,500 feet, so I’d already climbed almost 400 feet. The trail was excellent, easy to follow, well-maintained. It zigzagged a lot to avoid outcrop and brush, but I was able to keep a good pace. Time passed. As I continued to climb, I passed over 10 bumps along the way, most of them small but a couple of them a hundred feet or so high – each one required dropping back down and losing some elevation, then having to regain it. By the time I neared the 5,900-foot point, the trail dropped down from the ridge proper then climbed slowly again into a more wooded area known as Juniper Basin. There was a rustic campsite there at around 6,000 feet – it looked comfortable enough, and I laid out my sleeping bag for the night. It had taken just under 3 hours to get this far. Almost 8 miles, and 3,895 vertical feet under my belt on this first day – a good effort, I thought, for a 40-year-old non-backpacker like myself. I had the campground to myself, and slept well.

As an aside, I have a Tanque Verde story to tell you. One day, as I was watching the weather report on a local Tucson channel, the woman mentioned something about the “Tanque Verde Mountains”. I picked up the phone and called her, informing her that there was no such thing as the Tanque Verde Mountains. She disagreed, and said that a friend who worked for the US Forest Service had given her the name. I told her that the USFS was one of the worst offenders for using non-official names, then attempted to tell her that names that appear on maps are carefully chosen and approved by the United States Board on Geographic Names. If they haven’t approved a name, it isn’t official. Well, her nose got all out-of-joint when I told her this, and she wasn’t buying it. I was glad to see her pack her bags a few years later and move to a city that was a real hell-hole compared to Tucson – she didn’t deserve us.

Day 2 – March 11, 1988

The next morning dawned clear. I got ready quickly (since I wasn’t cooking any food on this trip, that was time saved) and was packed up and moving by 6:35 AM. I got my early-morning workout right away as the trail turned to the north and climbed a thousand vertical feet in 2 miles. Near the top in sheltered spots were a few snow patches, but the trail was otherwise clear and easy to follow. This was my first summit of the trip. Tanque Verde Peak had an elevation of 7,060 feet. The trail now continued east along the crest of the ridge, slowly losing elevation as it crossed over numerous small bumps. It climbed about 200 feet to gain Point 6537, then dropped over 400 feet to deposit me at a place called Cow Head Saddle. There I was, at 8:23 AM, with about 4.5 miles under my belt so far on the day. It was a sunny, friendly spot and I lingered a while. Later in the day, I took a picture looking back west and here is what I saw. It shows Tanque Verde Peak, but also a portion of the very long Tanque Verde Ridge. My climbing route went from the left to the right, up and over the peak.

Reaching Cow Head Saddle seemed like a milestone of sorts – I’d heard the name for years, in the context of its being a marker along the route to reach the range high point. The saddle was a 4-way junction: if you headed downhill to the north, you’d reach the Douglas Spring trailhead at the east end of Speedway Blvd. in eastern Tucson after about 8 miles; if you headed south, you’d eventually reach the Madrona Ranger Station; west would take you back the way I’d come, along Tanque Verde Ridge; east would take you up into the high country of the Rincon Mountains and to Mica Mountain, and that was the way I was now headed.

The trail now climbed steeply, gaining 300 feet in a short distance, then eased up a bit but never quit climbing. In a mile and a half it had reached 7,000 feet, passing mostly through forest but sometimes across open, rocky areas. At around 7,600 feet it entered a shallow drainage and followed it up to pass by Helen’s Dome at 8,364 feet. I didn’t try to climb it, but did grab this quick view of it as I passed by.

In another mile, I went past Spud Rock, once again not stopping to try it. I was now closing in on the prize, and at 11:38 I reached it – Mica Mountain, the highest point of the Rincon Mountains. I know it doesn’t look like much, a flattish area in the forest, but there it was, all of 8,664 feet elevation.

This was actually my main goal of the trip, climbing Mica, but I still had a very long way to go. Below Mica, there was quite a bit of snow in the forest, as you can see in this photo.

A couple of miles of downhill took me to a spot called Manning Camp at 7,940 feet. I stopped long enough to take this picture. It was allowable to camp here, but was not on my agenda.

Here’s a link to this historic structure that will tell you more about it than I ever knew. It was a little after noon by the time I left the cabin. My route continued south to around 7,500 feet, where I then headed east, passing Devil’s Bathtub Spring. Not far beyond that, my trail intersected another, which I chose and followed it south. Most of the time I was descending through the forest, but the trail did go up and over another significant bump of 300 feet, taking me back up to almost 7,400 feet. From there, it was more southerly travel through the forest along a ridge, which finally climbed back up to the site of Happy Valley Lookout. There, at 7,340 feet had stood a US Forest Service forest fire lookout in previous years. It was a good spot, for sure, as you could see everything around you for many miles. Here’s a view to the west, looking out to the long, dark Tanque Verde Ridge. It had taken me yesterday afternoon and also this morning to walk its entire length.

Now here’s a look back north the way I’d just come, the many miles back to Mica Mountain. That huge expanse of rock over to the right is known as Reef Rock

And finally, here’s my favorite view from the lookout, to the south, to my next goal, Rincon Peak. It’s gonna be a long, hard march to get there. The low spot in the forest below is Happy Valley Saddle, my next goal

A long series of switchbacks dropped me down a full 1,300 vertical feet to the saddle. My permit said I was to spend my second night there, at 6,100 feet elevation. It’s a nice place to camp – flat, open spaces and there’s even a reliable water supply. Attractive as it was, it was only 3:20 PM and I felt I could push on farther. Barely stopping to catch my breath, I walked right through the campground and kept on going. I did have this view of Rincon Peak from where I should have camped, though.

The next couple of miles were fairly level, only climbing 200 feet. I was getting closer to the peak, as you can see from this view through the trees, but I still had a long way to go.

The trail set a merciless pace, now climbing steeply. There started to be patches of snow in the forest as I gained height on this shaded, north side of the peak. The higher I went, the more there was. I was fading fast – I had entertained the fantasy that I could make it all the way to the summit of Rincon Peak by nightfall, but it was not to be. 1,300 vertical feet of steep climbing did me in. I called it quits at 7,400 feet, unable to go any farther. It was all I could do to find a fairly level spot to lay out my sleeping bag a few feet from the trail. The forest floor was steep, and deep in snow – hard, slippery snow.

It was 5:15 PM when I crawled into my sleeping bag. My spot wasn’t completely level, so I had this nagging fear that I might slide downhill. I lay there, munching granola bars and thinking about my day. It seemed like an eternity had passed since I had slept in Juniper Basin. One luxury I had allowed myself on this trip was a tiny radio with headphones. I tuned in to the NPR station in Tucson and listened to a reading from Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, finally falling asleep. I was content with what I’d done – a full 22 miles and just over 7,000 vertical feet of climbing, all done with a full pack.

Day 3 – March 12, 1988

After a pretty decent sleep, I packed up quickly and set out at 6:30 AM. The trail was steep and relentless, but I felt energized and stormed up it at a good pace, climbing that last thousand vertical feet in just 45 minutes. There I was, on the summit of Rincon Peak, elevation 8,482 feet. It was the 3rd of the 3 main peaks I’d hoped to do on this trip, and I was pretty stoked. A huge cairn of rocks marked the spot, and as I sat there admiring the view I heard a strange noise. Now keep in mind that I had met no one else on this entire trip, not a soul, and other than the wind, birdsong, the crunch of my boots and my heavy breathing, there had been no other sounds. So now I was hearing this odd noise, kind of a roaring sound. I looked up, and there was a hot-air balloon! It was moving quickly, from west to east. It must have come from Tucson. The roaring was from firing its burners. When I first heard it, it was almost directly overhead, but the strong wind was blowing it east at a rapid pace. I don’t think I heard the burners but once or twice, then it was gone. And it wasn’t much higher than the summit where I stood, so I had a good look at it, albeit for a short time. Well, that was unexpected! I found the register and signed in, then prepared for the last part of my journey. Here was my sunrise view from the mountaintop, the shadow of the peak filling the valley below.

From here, it was all downhill – all I had to do was let gravity carry me, keep heading south down an endless ridge and before long I’d arrive at my waiting truck. I felt good, excited at the prospect that I’d be done soon. Oh, wait – here’s one more view from the top, one looking back the many miles to the north, to Mica Mountain.

Okay, time to leave. I could see down the wooded ridge to the south, and I could plainly see my next objective, something called Wrong Mountain. It was about 400 feet lower, and only 0.7 of a mile away. Here’s a view of it taken after I had started down. It’s the rounded bump with all the snow on it. See over on the right side, the outcrop sticking up in the sunlight? – that’s part of it, and that rock can be seen from the desert floor many miles away.

Now keep in mind that the moment I set out downhill from Rincon Peak, there was no more trail. All the many miles I had covered to this point were on excellent trails, making for easy going and quick progress. I knew it’d be slower from this point on, but it was all downhill, right, so how hard could it be? I’d have to be doing some serious orienteering with map, compass and altimeter, and doing it constantly so as to never lose track of my exact location, but that was okay, I expected nothing less. As I continued downhill, I noticed that it was very brushy, enough so that I had to try to find lanes through it. The closer I got to the peak, the tougher the brush became, so I thought to myself “This is just Wrong!” (Sorry, I couldn’t resist.) By 8:22, I had worked my way down to, and stood atop, Wrong Mountain. At 8,056 feet, I was still pretty high.

I was looking at today’s climbing as being a series of bits that I would do, one after another, so that I could just focus on one bit at a time. The farther I went, the more remote my location became, so I really had to be paying attention. For the next bit, I would continue south from Wrong Mountain, in the process dropping another 300 feet to get me to Point 7776. It too was in plain view and less than a mile away. Down I went, but the brush became worse and it took some hard work to plow through it. It was 9:00 AM when I arrived. It turns out that 7776 is the highest point of the entire Rincon Mountain Wilderness Area. When I arrived, I found that someone had built a huge cairn to mark the spot – probably officials from the monument, or surveyors.

So far, so good. It had taken me almost 2 hours to drop about 700 vertical feet, but I had only covered a mile and a third. Hopefully I could pick up the pace for a while. I headed east from 7776, the terrain being fairly flat for a bit, getting my bearings for the next stage of my day. What I saw was really depressing. Have a look at this next picture, and I’ll describe what you’re seeing.

It may not look like it, but everything you’re seeing is steeply downhill from the camera. My goal was to get to the area on the far left side of the photo, on the skyline. Below that point are huge cliffs, as much as 1,500 vertical feet tall, so obviously I couldn’t deal with those. I had to get around them, and the logical place was way over on the right side of the photo. See the short tower of rock down the slope all by itself and surrounded by vegetation, at about 4 o’clock from the exact center of the photo? I needed to get down to that and then figure things out from there. Down I went, but the brush was awful – it was mostly manzanita, and it resisted me at every step.

I finally got down to the tower and climbed up it – this put me at 7,000 feet. Wow, talk about a front-row seat for those cliffs! Here’s what was staring me in the face – this was some dramatic country.

The peak I was trying to reach is on the far left side of the flat terrain up on top. The only sensible way to get there was to drop down another couple of hundred feet and make my way off of the right side of the photo, traversing across until I was rid of the cliffs and could climb up through easier ground. That would give me about 500 vertical feet of climbing to reach the top.

Then began one of the ugliest bits of climbing I’ve ever done in 57 years in the mountains. I started down from the tower on a descending traverse, skirting below the cliffs and trying to not get tangled up in them. The going was horrible, small trees mixed in with manzanita and the occasional prickly-pear cactus. I finally got far enough over, to a point where I could begin to start uphill again. The manzanita became thicker, closer together. I looked for lanes between it but rarely found anything I could use. When I climb, I always wear long pants and long sleeves, mainly to protect against the sun. Today, I was glad to have it for the bushwhacking.

My uphill progress was glacial – it felt like I wasn’t getting anywhere. I tried climbing over it, through it, even under it. Of course, my backpack was a real hindrance – it kept getting caught. I was in the middle of some of the healthiest manzanita to be found anywhere on the planet. Taller than I was, as thick as could be. Its branches are like spring steel, very hard to break. You push against it and it pushes right back. I remember vividly how at one point I was lying under a bush, my face in the dirt, trying to crawl forward, my pack caught on branches above me and unable to move. I also recall standing on the steep mountainside surrounded by a sea of manzanita – it looked equally awful in every direction – and swearing at the top of my lungs, as if somehow that would make it better. Things were not only about as bad as they could be, but a great deal worse. The stuff was soul-destroying. I bravely tried to keep going, but how painfully slow was my progress. It was the type of climbing that I had only previously experienced in nightmares.

They say, about bushwhacking like that, that if it doesn’t kill you it damages you. Well, I was damaged alright. By the time the slope eased up and things leveled off, my clothes were shredded. I’ve always wished I had taken a picture of myself at that point. My shirt was torn into strips, from shoulder to wrist, the front too (the backpack had shielded my back from the manzanita). My pants were torn into shreds and of little use for the rest of the trip – I would have been almost as well off just in my underpants. And there was blood aplenty – it looked like I had been attacked by pack of badgers.

Now, all I had to do was walk from west to east across the top of the mountain, crossing over 3 intervening hills to finally reach the top of Peak 7325. As I did this, I was traveling around the head of a cirque which contained a feature called the Valley of the Moon. High marks go to the person who named this, it certainly was other-worldly. By the time I stumbled on to the summit, more than 2 hours had passed since I had left Point 7776, and yet, measured horizontally, I was only 4,000 feet from it. I left a tiny register in a 35-MM film container because there was none there, and hid it inside a cairn. Four years later, peakbagger Mark Nichols would climb up to this peak from the east, and would replace my register with a glass jar, much more permanent.

That had not gone well. I was so worked up, I wasn’t even hungry. I want to show you a photo that I’ve marked, so you can see what was next. You saw this photo earlier, but now it should make more sense. Allow me to describe what you’re seeing.

The yellow line starts from the small tower, goes down to the right, through the dark area of trees and brush, then begins a steep climb uphill to reach the higher ground. From there, it winds its way back across to the left to the edge of the photo where you see 7325, which is the top of the mountain. From where it climbs up and reaches the higher ground, it only climbs another 80 feet or so to get all the way around to 7325 – all of that is fairly level going. The Valley of the Moon is beyond the yellow line as it makes its way along the edge of the mountain up on the higher ground, and is not seen in the photo. However, if you click on the link above for Peak 7325, you will see it on the map that opens up.

Look at the photo again, and you’ll see 2 more bumps labeled – they are 7202 and 7056. To give you a sneak preview, think of this: the distance from 7325 all the way down to 7056 is one quarter of the distance I still had left to cover to reach my waiting truck.

It was time – continuing south down the ridge towards 7202, I had no misconceptions about how bad the brush would be. It lived up to my expectations, and then some, but at least now I had gravity on my side. Reaching 7202 put me beyond the Valley of the Moon. Every one of the bumps along the ridge had to be climbed up one side and down the other – some were small, others annoyingly-larger. For example, 7202 was only 80 feet, but 7056 was 160. It was half-past noon when I reached 7056.

Beyond 7056, the ridge split into 2 branches, and I chose the eastern of them. This forced me to climb up to a bump at 6,800 feet elevation, a rise of 120 feet, then down again. The next thing along my path was a bump at 6,613 feet. In this next photo, it is the darkly-wooded bump on the right side, and it required 200 feet of climbing to get beyond it.

It was almost two o’clock when I stood atop Point 6613, and as you can see from the photo, I still had over 2,000 feet to descend to the desert floor. I was so ready for the interminable bushwhack to end.

Ever since Peak 7325, I had been heading south. Point 6613 was a major landmark for me, because from atop it I had to make a major change of direction – I would head east, steeply downhill, crossing over the very head of Martinez Wash, then down a gentle ridge and over Point 4590. I was almost there – I could see the corral in the distance, maybe a mile to go. By the time I covered the last stretch on open ground, it was 3:45 PM. My truck was as I had left it, and it sure looked good. The corral and truck were at 4,300 feet elevation. The horses had guarded it well, and I thanked them for their watchful gaze.

Here’s one last look back from the corral, back to Point 6613.

It was hard to believe it was over. The trip had spanned parts of 3 days, but in reality had taken about 48 hours by the clock from start to finish. I had no cell phone, no GPS, no rescue device, but did have good maps, a compass and altimeter. I never felt concerned at any time, but did feel some regret because I’d gotten so worked up about the bushwhacking on this last day.

The total distance covered was just a shade over 40 miles, with 13,840 vertical feet climbed. I’m happy I did it, and look back on it as a pretty decent piece of mountaineering. Still, to this day, I regard it as the worst bushwhacking I’ve ever done.