During 1967, I had made the decision to switch my major at the University of British Columbia from zoology to geology. It meant an extra year of studies, but the payoff was that at least I would have a job to go to upon graduation. 1967 turned into 1968 and I plodded through a very full load of courses – my grades were mediocre at best. Came late April and I was wrapping up my final exams. I already had a summer job arranged, this time with Falconbridge Nickel, and the guy who hired me was named Dave Brown. He had made a name for himself as the guy who had discovered a major orebody back east in the Noranda area of Quebec years earlier. From Day 1, there was something a little off-putting about the guy. He was a tightwad, and could pinch a penny hard enough to give the Queen a headache. I ended up settling for a salary ($450.00 per month) that was less than I could have obtained with the competition (my fault), and he wasn’t even prepared to provide a warm sleeping bag for the field season. That may not seem like a big deal, but in mining exploration the company always provided a good sleeping bag for its workers on summer jobs. I finally convinced him to include one as part of the package.

I started work for Falconbridge on April 29th in the position of Junior Geologist (I was still a year away from graduation, so it was nice that they gave me that recognition), spending the day in the office in downtown Vancouver poring over air photos and topo maps. We dined at my boss’s home, then drove all the way to Spences Bridge, 200 miles, putting us into town very late. The next day was spent with a guy who had a group of mining claims in the Highland Valley, and later we drove all the way back to Vancouver by midnight. Perhaps that had been a trial run and he was checking me out to see if I had a clue.

After a few more days in the office, it was time to head into the field. It turned out that the company owned its own helicopter, a Hiller FH-1100, a 4-seater which some of us considered to be the poorer cousin of the Bell Jet Ranger, but hey, it was a chopper which could serve us full-time in the field and that was a big plus. I don’t know what the cost of one of these was, new, back in 1968. However, I did discover that a new one in 2005 cost $925,000.00 USD. It could carry 1,400 pounds including passengers and pilot, and had a cruising speed of 127 mph with a range of 350 miles fully-loaded.

The pilot and I flew from Vancouver to Lytton, which took 1 1/2 hours. There, we waited for others who had driven the distance, and finally, late in the day, we flew up the Stein River to a group of mining claims which were 20 miles upstream. It was the 3rd of May. The chopper transported 4 of us and all our gear in 2 trips.

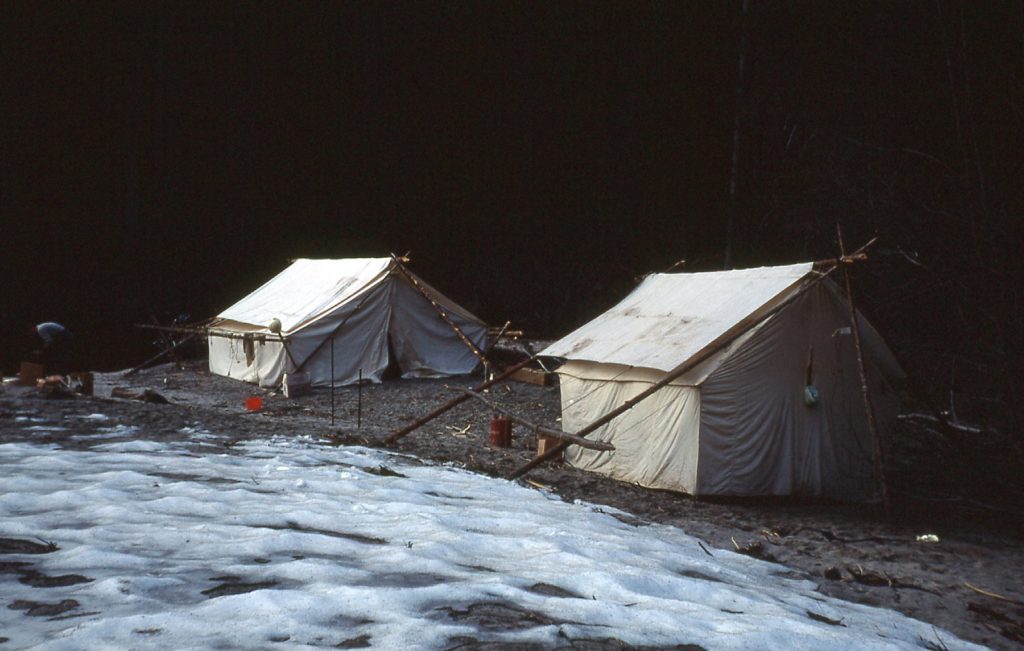

The next days were spent doing geological mapping, and we worked hard, prospecting and mapping up to 4,100 feet elevation in Rhyolite Creek and Nesbitt Creek. That work involved climbing as much as 2,000 vertical feet. There were plenty of clouds, but no rain. Parts of some days I’d spend in camp working on my geological maps and my report. We even forded the river a couple of times to check out the geology on the other side. Here was our camp for those days.

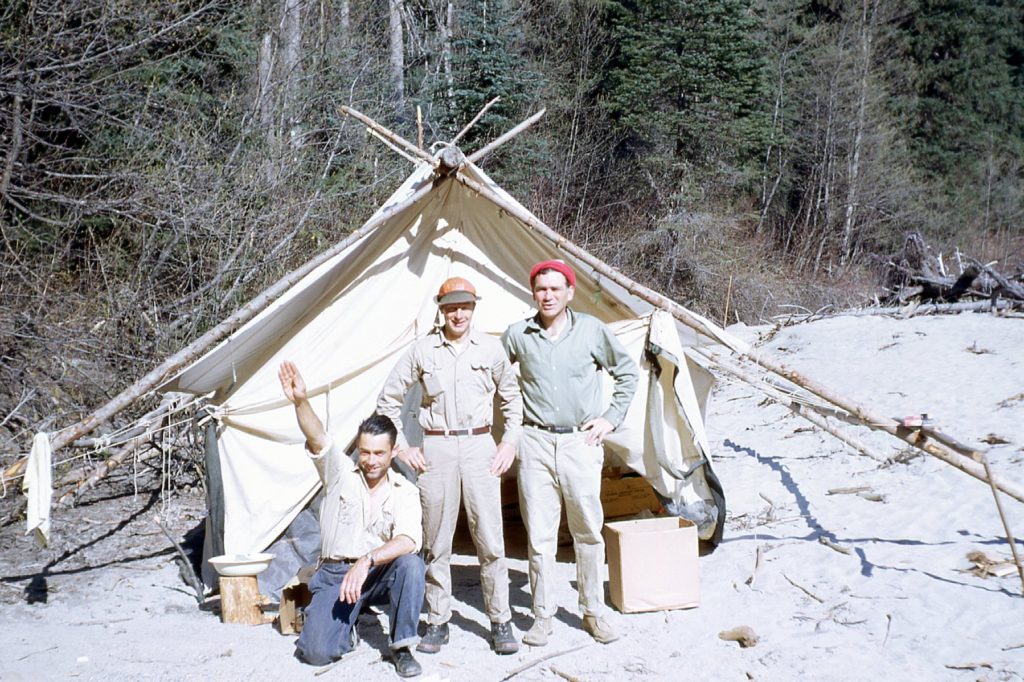

Did I mention there were 4 of us? Here are my 3 companions – keep your eye on the one on the right. His name is Don Hamilton, and he’ll play an important role later on.

In 1968, the entire Stein River drainage was pretty wild, undisturbed country. In the 1980s there was a plan afoot to start logging there, but environmentalists raised such a hue and cry that, instead, by 1995, a large provincial park was created which includes pretty much the entire Stein River watershed. This protected the area, which is sacred to the local First Nations people, and created a recreational area which is today enjoyed by many. It is still wilderness, though, the only access being foot trails. There are even a few cable crossings of the river to facilitate getting around. Here’s what things looked like when we were there. In the next dozen years, I’d return to the area and climb several peaks both north and south of the Stein.

During our last night there, something curious happened. The shouting of one of the guys woke us all up, and we all jumped out of our sleeping bags to see the river overflowing its banks. It was rising quickly and threatened to sweep our tents and everything else away. You never saw such a flurry of activity in your life. We pulled down the tents and dragged them, along with everything else, to higher ground just in time to avoid a disaster. The river may have claimed a few things, but nothing of significance. Suffice it to say that none of us got any more sleep that night.

In the morning, our chopper arrived with the bosses from Vancouver. We flew up to the most interesting part of the mining claims and I showed them what I’d found. We all agreed that it was of little importance geologically, and the claims were allowed to lapse. The chopper ferried all of us and our gear back out to Lytton in several trips. Then began the trip north, where we would spend the entire summer working. My notes say that we stopped in Clinton for a few beers, then more of the same in Williams Lake where we spent the night in a motel and enjoyed a hot shower after a week on the Stein River. The next day, we passed through Prince George and made our way west to the town of Burns Lake, where we settled in to the pub and eventually checked in to a motel for the night.

Early the next morning, we used a boat we’d been hauling around and traveled 3 miles on Decker Lake just outside of town to a group of claims in the bush on the other side of the lake. There, I found some interesting mineralization.

Notes and sketches made, back across the lake we went, then drove another hour west along Highway 16, known as the Yellowhead Highway, to the small town of Houston, BC. A mile south of town, we checked in to the Houston Cabins which would be our home for the next month. Living in a spot like this is always better than living out in the bush. We could eat in nearby restaurants and drink beer in the local pub.

The next 3 days were spent driving the back roads for many miles around in the area of Houston, trying to have a look at known mineralization. We were often stymied by snow in the bush and also in places along the roads. Finally, on May 14th, our chopper arrived and parked itself in a grassy area opposite the cabins. Now there’d be nothing to stop us from getting out into the back-country. We still used our trucks to get around to a lot of places, though, usually in a convoy of two. More manpower was useful when we’d bog down on the muddy roads, like this spot near Buck Creek. This axle-deep episode took 3 hours to escape.

Now that our chopper was with us full-time, our routine changed, at least for a lucky few like myself. Typically, our pilot would drop two of us off in high country, in a spot like a mountaintop, and we’d spend the day prospecting our way downslope to get picked up by him at the end of the day. This wasn’t as easy as it might sound, as we often floundered our way through deep snow and thick bush. This picture shows what would have been a pretty typical day. We’d fly over the valley bottom and agree on a spot where the pilot could pick us up at the end of the day. Then the pilot would fly us to a clearing high on the mountain and drop us off. As you can see, there’s still plenty of snow everywhere.

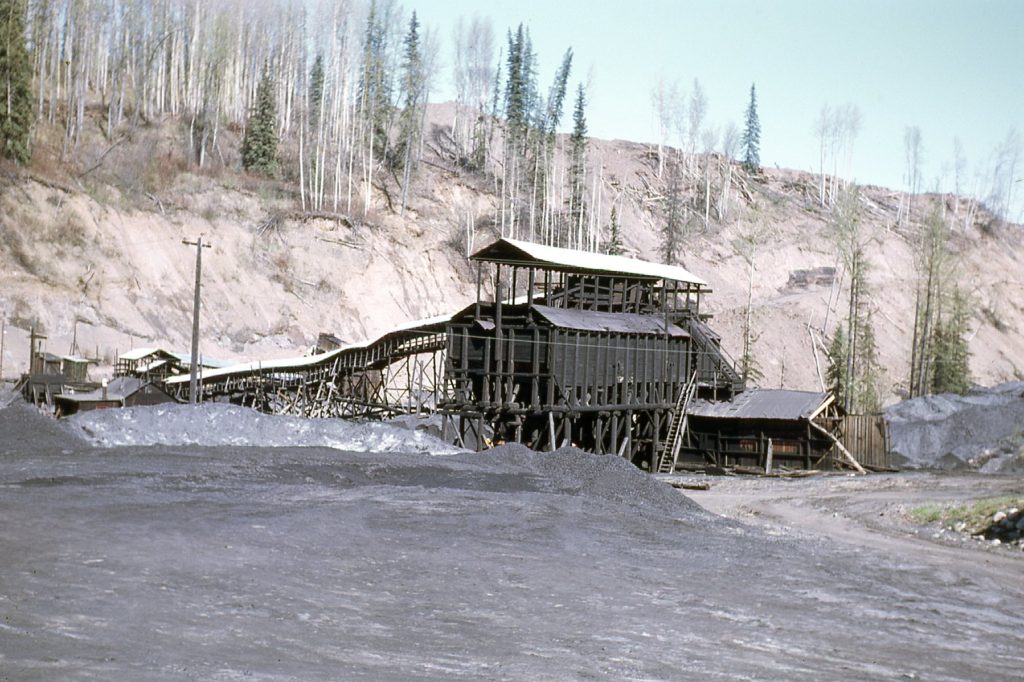

There was a group of mining claims high up in a mountain valley we were interested in studying, optioned from some guy. We planned to spend a bunch of time there and do, among other things, geological mapping. In mid-May, when we first went there to have a look, we found the area covered in deep snow. It was going to take Mother Nature a long time to melt all of that off so we could have a proper look, so we decided to give her a helping hand. Bulkley Valley Colliery was only a few miles from the town of Telkwa, and they agreed to sell us coal dust. I don’t know if the dust was used for anything in particular, but as a by-product of their mining operation it was abundant. Our entire crew drove out there on May 17th and by the end of the day we had filled 94 gunny sacks with coal dust. Then, using our chopper, we’d hover over the snow-covered mining claims and pour out the dust, one sack at a time. The downwash from the chopper blades blew it down on to the snow. Of course, the black dust on the white snow made it really easy to see where it had landed. As the weeks passed, it was easy to see that the area we had dusted melted off much more quickly than the surrounding untreated area, allowing us to get in there and get the work done.

On May 26th, a Sunday (crews in the bush worked every day, and only got a day off when the work allowed, but usually got a bonus added to their monthly pay to compensate for the extra time worked), work started normally enough. Pairs of guys were dropped off by the chopper out in the bush, and everyone knew their pick-up point for the day’s end. Somehow, one of the guys, Gunnar, got separated from his partner and wasn’t at the appointed pick-up point when he was supposed to be. The pilot circled around and couldn’t find him, so he radioed the bosses back in Houston. They grabbed every man and all drove out to the nearest approach by road to the pick-up point. The pilot then ferried pairs of men to spots out in the bush where they could search for him. Every team had a 2-way radio to keep in touch. Well, it took several hours (thank goodness for the long days that far north), but he was eventually spotted and retrieved safely, none the worse for wear. He was lucky.

Believe it or not, the next day the same thing happened, this time with a guy named Don. He too was located after several hours of searching, unharmed. Earlier in this piece, I said we’d need to keep our eye on this fellow. His name was Don Hamilton, and I was paired up with him for quite a few days. He was a quiet sort, moody and brooding at times, but we got along well together. Here’s a photo I took of him a few days later when he and I were out prospecting for the day. Don was probably twice my age, maybe 40 to my 20. He was the only guy I ever knew in Canada who had a handgun. Aside from law enforcement, prospectors were among the rare few who could apply for and obtain a permit to carry a handgun – I suppose the thinking was that they ran a risk from wildlife as part of their work out in the boondocks. He carried his .44 magnum revolver with him every day he was out in the bush.

As an aside, one day the pairs of guys out prospecting encountered, collectively, 10 bears and 4 moose while on foot. Personally, I was never scared seeing such wildlife and rather enjoyed those encounters.

And now, for the rest of the story. A year or two after that summer of 1968 when I worked with Don, he was up at the ski resort of Whistler, 75 miles north of Vancouver. It’s one hopping place in the winter. He went into a convenience store and asked them if they’d take his personal check to pay for his purchases. They said no, that it was their policy to never take personal checks. He couldn’t convince the clerk to change his mind, so he went out to his vehicle, grabbed his .44, went back in and blew the clerk’s brains out. He was arrested and tried for capital murder, then sentenced to life in prison. When I heard about the Whistler incident, I was really glad that I hadn’t ever pissed him off when we worked together in the field all those days!!!

By this time, our crew was up to 18 men. The bosses decided that we all needed to improve our use of map and compass, so they devised a test for us. They drove us all to a place where 2 roads ran parallel to each other and were separated by several miles of bush, lakes and swamps, all quite flat. They dropped us off at precise 1/4 mile intervals along the western road, then told us that, by using only map and compass, we would all head east through the bush, all of us starting at the same time. The idea was that if we were any good at all, we would head in a straight line and would all come out several miles away on the eastern road and we would still all be 1/4 mile apart from each other. It seemed like a simple enough idea, right?

The bush was plenty thick, with visibility rarely more than a hundred feet, so it’s not like you could see each other and maintain your spacing. There were interesting challenges – you’d come to the edge of a swamp, which you’d have to go around in order to continue. The idea was that somehow you’d memorize a feature on the other side of the swamp, go around and try to find that feature, then continue from there. I remember that I came upon a clearing in the dense forest where I saw literally dozens of moose antlers that had been shed, all in that one spot – I didn’t know they did that. We all had a copy of the same map, and each of us had a reliable compass provided by the company. I think the distance from one road to the next was perhaps 5 miles in a straight line. The bosses waited in vehicles along the eastern road, and recorded the exact spot where each man emerged from the bush. Well, you’d have to have been there to see the result – it was a laugh riot. There was no one who emerged where he was supposed to be. In some cases, a man had crossed over the paths of as many as 3 other men en route!! Boy, talk about a sobering experience.

On June 6th, my boss learned that I had been driving their company vehicles without a licence. Okay, truth be told, I had a driver’s licence but it was for motorcycles only, not for anything else. He was not amused. He made some phone calls, and it turned out that I’d be able to take the driver’s test the next day. In those sparsely-populated areas of northern BC, there was a roving driving examiner who visited small towns about once each month, and guess what – the very next day was the day he was in Houston. The next morning, I took my driver’s road test in a company van I’d never driven before. Fortunately, the town was flatter than piss on a tin plate, to quote me old Dad, so I didn’t have to do things like start from a stop on a hill. I passed, and my boss was appeased.

It was now June 8th – something major would now happen to affect the outcome of this story. The title is “Heaven and Hell”, and I’d have to say that up until now I hadn’t really had to go through any real hell, but that was about to change.

Stay tuned for the continuation of this saga which will be called “Heaven and Hell – Part 2”