During a break from my teaching activities back in 2016, I planned a climbing trip to one of my very favorite places, the Sauceda Mountains. I’d go out on to the Air Force bombing range once again, but this time I’d stay inside what they call Area B where it’s okay to be any time as long as you have a permit, which I did. Hey, I wouldn’t even need to stealth my way in, unlike so many other climbs on the range. It was Wednesday, February the 26th, when I headed in. I camped just a few miles into the range and was settling in for a nice evening when a white pickup showed up. Two guys got out and asked me for my permit. They were the rent-a-cops hired by the Air Force to police the range. I complied and they called it in to their headquarters – I passed with flying colors, having called in the details of my trip beforehand, so I was legit in their eyes. They left me alone, driving back to HQ (they are never out after dark).

Early the next morning, I set out from the truck for a massive 3-peak day, done in a big loop. I was completely knackered by the time I finished at 3:30 PM. After changing out of my sweat-soaked clothes, I headed straightaway towards my next peaks. Here’s a lovely strip of the Saucedas along my path in the waning afternoon.

Driving southeast brought me closer to Hat Mountain. The shape of the summit is so distinctive, it can be seen from many miles in every direction.

The road brought me very close to the peak, and the land to the north of it was perfect for camping. There was a good view of the 2 peaks I wanted to climb in the morning, and you can see them both in this photo, but they’re out there a ways. On the center skyline is a big gentle summit – that’s 2404; lower down and well over to the left is a darker peak, more pyramidal in shape – that’d be my second one, 2202.

Driving farther in afforded me this better view of Peak 2202.

From my campsite, this was my new view of Hat, due south.

If I turned right around, this is what I saw looking north – another piece of the Saucedas where I would spend considerable time in the next few months.

I unloaded my truck so I could sleep in the back, then heated up some beans. The day was shedding the light softly and I was treated to a majestic desert sunset.

Before I knew it, it was as dark as the inside of an undertaker’s hat. After a good night’s sleep, I packed up early and drove farther north up the valley to where an old road left mine. This sign greeted me and I parked.

Unsure of what awaited me up this lesser road, I shouldered my pack and started out at 6:53 AM. It was easily followed and I made good time, reaching its end 20 minutes later. Imagine my surprise when I found this tinaja, a natural depression in the rock where water could sit for a lengthy period. I could safely say that there were thousands of gallons at the time.

But look at this, what was above the pool – a good 50 vertical feet of rock.

I had to explore more, so I climbed up the easier rock over to the side and found myself on the top. And what to my wondering eyes should appear, but this structure. Do you know what it’s called?

I walked to the far end and took this picture looking back.

And here’s a close-up.

Those of you readers who are in construction, engineering or even some aspects of landscaping will recognize this thing I’ve been showing you. It’s called a gabion. The purpose it serves here is to filter out all of the debris, such as rocks, vegetation and even sand and gravel, which would be swept down from the channel up above in a heavy rain. All of that crap would collect behind the gabion instead of tumbling over the precipice and filling up the pool below. If the pool is filled with debris, there is less room for water, so animals wouldn’t be able to rely on it during hard times. This gabion was working extremely well, as the pool below was clean and deep, and had been that way for many years. The brown metal stakes were set into solid rock, so this was one for the ages. Good job, Game and Fish guys! Just above all of this was a camera – these guys like to know who or what, man or beast, has visited the spot to use the water. From top to bottom, we can see the antenna, a solar panel and then half-way down the mast sits the camera.

Now here’s the interesting thing about this water catchment – nobody knows it’s there. Of course Game and Fish does, because they built it. But no Bad Guys (border-crossers or smugglers) know it’s there because there is not the tiniest speck of trash anywhere near it – it is so well-hidden. They would have left some sort of a mess if they were using it. Now it gets interestinger from there.

A few miles away is a named feature on the map called Thanksgiving Day Tank. It is a water catchment which has been enhanced by Game and Fish to trap and hold more water whenever there is any rainwater runoff. It too has a gabion, as seen here, in addition to a masonry wall to act as a barrier.

The tank is all of concrete – no leakage here, only evaporation.

This tank I am showing you now is along a well-trodden path used by Bad Guys – they all know it’s there, and rely on it as a water supply. But it is not the real Thanksgiving Day Tank. The name was incorrectly placed on the map. The other tank, the first one I showed you at the bottom of the high cliff is not along any travel route, so is by-passed completely. I hope it remains that way forever. It is in fact the real Thanksgiving Day Tank.

I could see up the remaining 600 vertical feet of the climb, all the way to the summit. There it sat, with the full moon perched above it.

This cave was along my path. The Sauceda Mountains are riddled with caves like this. They make a perfect shelter from a thunderstorm. Brian Rundle and I once spent a comfortable night in one after becoming benighted on the way down from a technical climb high on a mountain.

From the cave, here is what I saw looking back down towards the tank.

The summit wasn’t far off now.

Here was the last bit left to do.

This nearby bump was slightly lower than the true summit.

At 8:15, I was done, standing alone on the summit of Peak 2404. The photo shows some of my stuff spread around: map; satellite rescue device; gloves; camera case; pack; register jar; the rolled-up register paper from inside the jar.

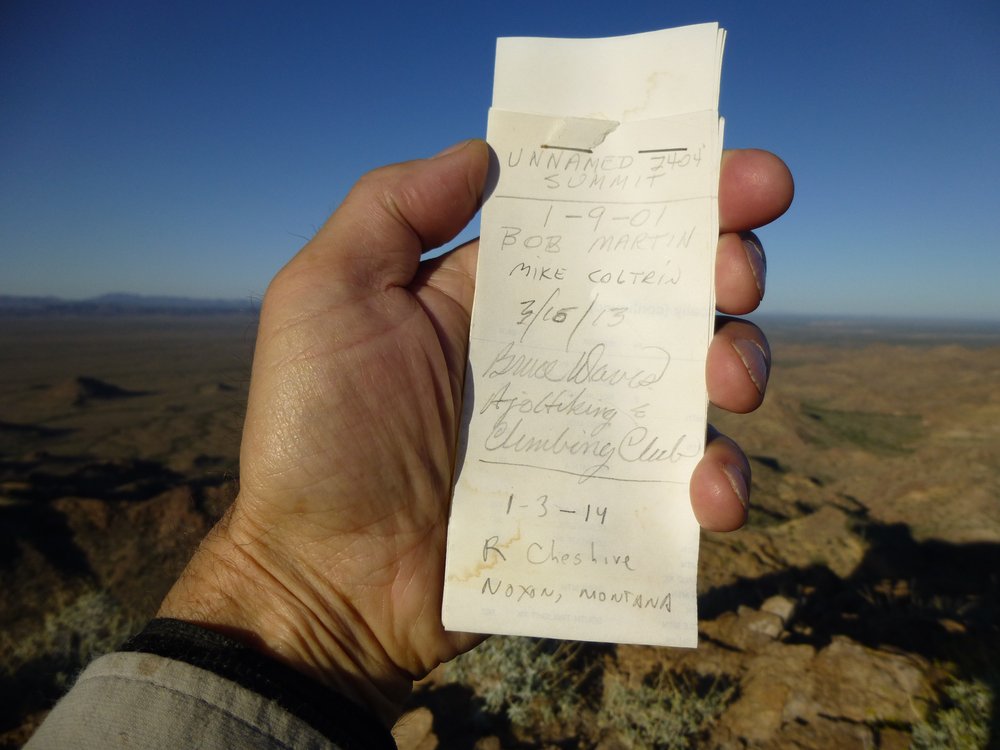

Here’s what I found inside the register jar. As you can see, 4 others had been there before me – in 2001, 2013 and 2014.

I spent a bit more than 20 minutes on the top. It wasn’t as if the scenery was bad or anything like that, but I had one more peak to climb and to do it I’d have to head cross-country on unknown ground, so I left. My idea was to head more-or-less in a straight line to the next peak, but still taking the path of least resistance. It involved dropping down almost 700 vertical feet, then starting the climb back up again to that final peak. From around that low point, I looked back up to Peak 2404 where I was earlier. It took me almost an hour to get down to this low spot.

All I had to do now was scramble up the remaining 400 vertical feet. I ended up on a trickier side of the summit, getting caught up on some Class 3 briefly, but it all turned out okay, putting me on top of Peak 2202 an hour and a half after I left the other peak. I left my own register here as I found none. Okay, I want to show you something. Here’s what I saw if I looked from the second peak back to the first.

I measured the distance from the first peak to the second with tools on my computer and it was only about 4,800 feet along the ground, so less than a mile. It was a bit convoluted but enjoyable. It was just after ten o’clock when I made it to that second peak. Remember how I said that yesterday I had done a 3-peak day, all done as a big loop. I want to show you a picture I took that day, looking ahead along one leg of the trip. I’ve drawn a line on the photo showing the path I followed. Zoom in if you need to. The piece seen in the photo was 1.1 miles long, just a small part of the 9.0 miles for the whole day. It makes me tired just looking at it, thinking that what the line shows was less than one-eighth of the day’s efforts

The top of my second peak today looked like this.

I could also see right down to where my truck was parked – can you see it? It’s right out in the open – zoom in if you need to.

Take a minute to find it – I’ll show you something else in the meantime. Check out more of the amazing peaks in these Sauceda Mountains.

Here’s one more.

Okay, did you find the truck? Here, I’ll show it to you. This is taken from the same spot as before, but zoomed way in.

It wasn’t far to go to get from the summit back down to the truck, and it only took about half an hour. Here’s a better look at the rocky summit of the peak.

Once back at the truck, it was still early, not quite eleven in the morning. A last look back up to Peak 2202 looked like this.

All in all, today was much easier than yesterday. It only required 4 hours to cover the 2.9 miles and 1,515 vertical feet. Climbing in such a scenic place as this is very satisfying, and I loved every minute of it.