1988 was a very good year, and a busy one too. I was up to my eyeballs in a project to climb all 204 peaks which encompassed the mountain range high points of Arizona. There were several other mountaineering projects on the go as well, and every spare minute was occupied. In amongst all of that, however, was a trip planned for the Rocky Mountains of Canada.

I set out from Tucson on June 10, driving my Toyota pickup – it had a shell on the back, and that’s where I would sleep. Heading straight up to Saskatchewan, I visited my old Dad for several days. When I told him I wanted to visit the Cypress Hills, where the provincial high point lay, he said he’d like to see the area as well. We convoyed the 400 miles to the place and settled in to the campground for the night. Turns out the Old Man hadn’t camped out for over 60 years and he was a little out of practice. He was going to sleep in the shell on the back of his pickup, but getting things organized for the night wasn’t going too well, and the air was blue with oaths. The next day, he swore off camping forever, donating to me a lot of his newly-purchased gear. We parted company and I headed further west, into Alberta.

On June 22nd, I parked near the Lake Louise ski resort known as Whitehorn (deader’n a doornail in the summer) and then backpacked on a good trail to a cabin called the Halfway Hut. This spartan structure was available to all passers-by at no charge, and I’d make it my base for the next 6 days. The weather held perfect for the entire time and I climbed several peaks in the surrounding Slate Range. They were Ptarmigan Peak (10,039′); Mt. Richardson (10,125′); Redoubt Mtn. (9,521′). Some days were spent just walking miles along trails to lakes and passes for the exercise. One memorable day along a trail, I met a couple of fellows who were older than I but seemed hale and hearty. Introductions done, I realized I had just stumbled into Don Forest and Glen Boles. Don was the first climber to finish the list of 11,000-foot summits in the Canadian Rockies. Glen is also a famous Canadian climber. They were flattered that I knew who they both were.

On the 27th, I walked from the hut back out to my truck, then spent a couple of days dawdling my way west into British Columbia. By the 29th, I met up with friends Brian, Scott and Harry at Glacier National Park (the one in Canada, not the US) in the middle of the Selkirk Mountains. We settled in to the Illecillewaet Campground, but only briefly. On the 30th, the 4 of us set out with full packs on the Sir Donald Trail, climbing over 4,200 vertical feet to reach our bivi site at the bleak, exposed saddle between Sir Donald and Uto Peak at 8,300 feet. We were here to attempt the famous northwest ridge of Mt. Sir Donald. I believe it was the first attempt on the route by any of us, which had been made famous by its inclusion in Steck and Roper’s 1979 book “Fifty Classic Climbs of North America”. From lower down, along the trail, we had this look up to the west face.

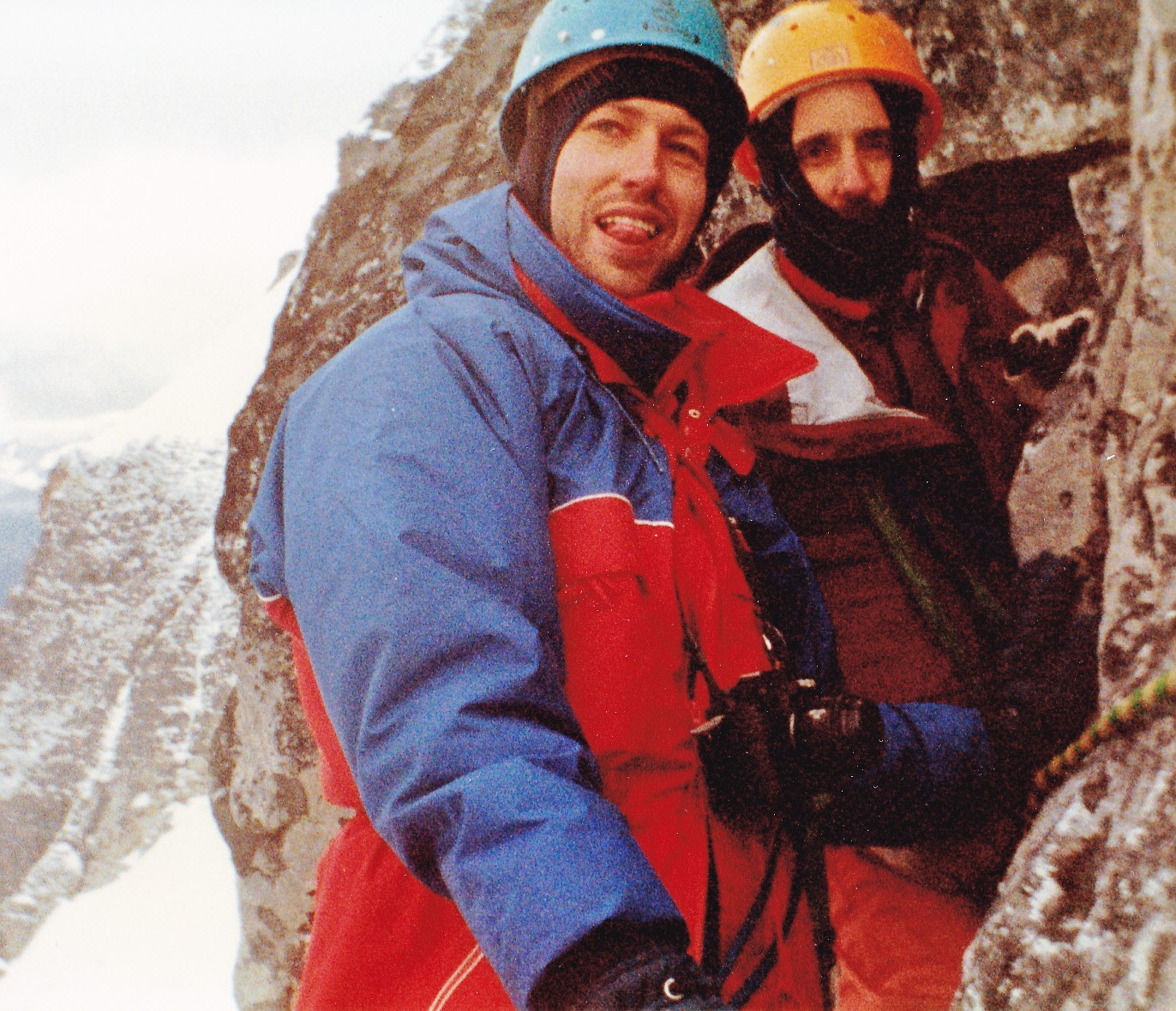

We spent the night at the bivi site in the saddle. Next morning, it was cold and trying to snow. As we got ready to climb, putting on helmets and harnesses, Harry decided that it wasn’t worth the hassle – he’d stay warm in his sleeping bag and watch our progress. Smart man! Our progress was so slow, the 3 of us on one rope on the icy rock, that by the time we called it quits we could still easily converse with Harry from our high point. We retreated to the saddle, packed up, and returned to the campground. I took this shot of Scott and Brian where we turned around on the ridge.

On the way down, we had this view of the Vaux Glacier.

Lower down along the trail, where we had re-entered the forest, I saw a porcupine and her baby – the only time I ever saw a porcupette. When born, they have soft quills that protect the mom during the birthing process. After a few days, the quills harden with keratin and become sharp.

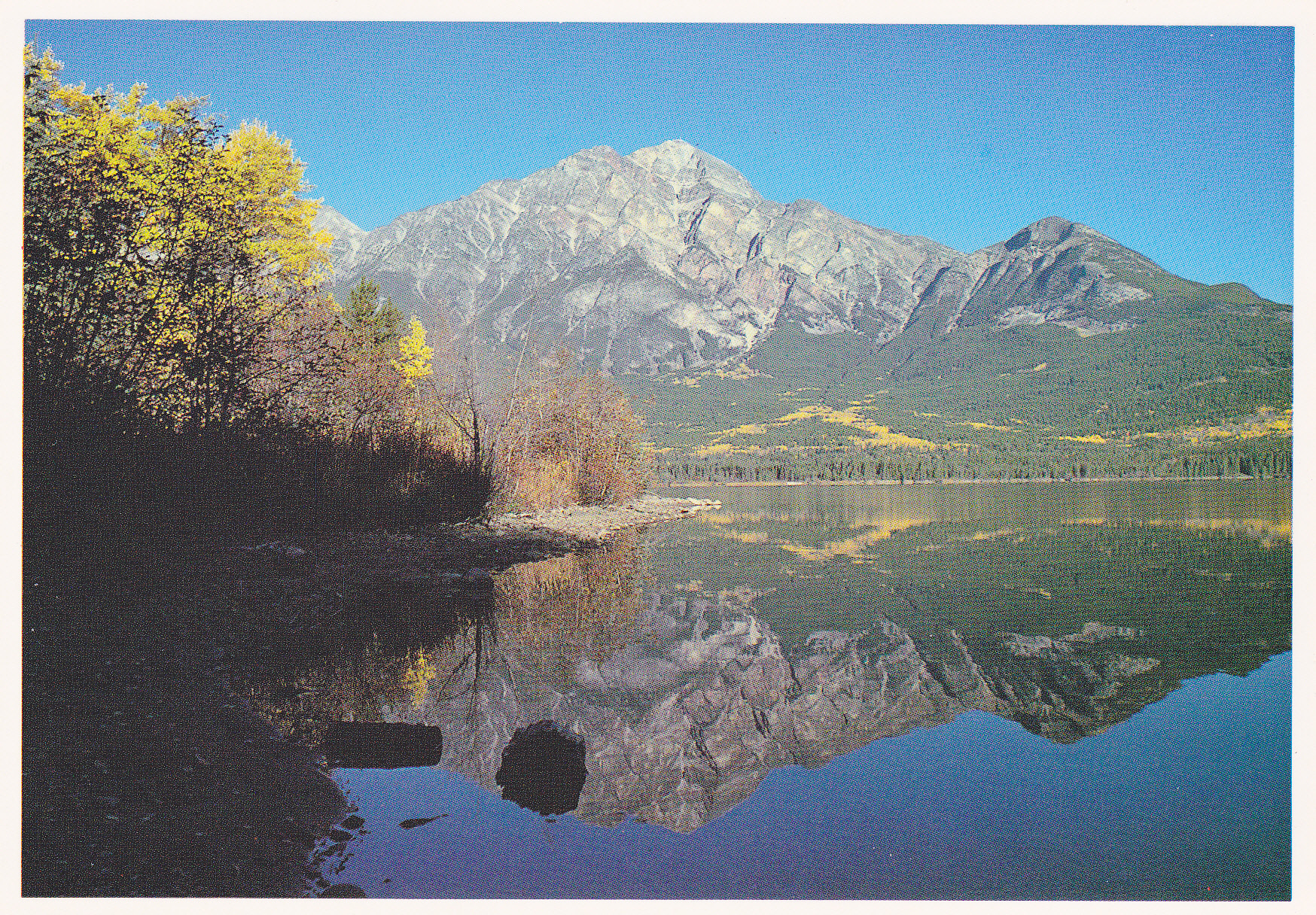

We left Glacier without the prize. I never tried Sir Donald again. We all convoyed east back to Lake Louise, then north to Jasper. By July 2nd, we were settled into a nearby campground, and the following day we all did a climb to the top of Pyramid Mountain just north of the town. This postcard shows it better than my own picture.

We spent time fantasizing about climbing Mt. Robson (the Monarch of the Canadian Rockies; the Great White Fright), even going so far as to contact a famous retired mountain guide named Schwarz who lived in Jasper. The Schwartz Ledges, a well-known feature on the south face route, had been named after him. We asked his advice, but at the end of the day decided that we weren’t even remotely ready to take on such a climb.

On the 5th day of July, the 4 of us set out to climb Mt. Edith Cavell, an ultra-prominence peak south of Jasper. We started off on the west ridge route. Harry said he wasn’t up for it, so he waited by the side of the trail for our return. It was a long day – we climbed 7,100 vertical feet over a 20-mile distance. We got our summit, though, found Harry on the way back, and starting planning for our next climb.

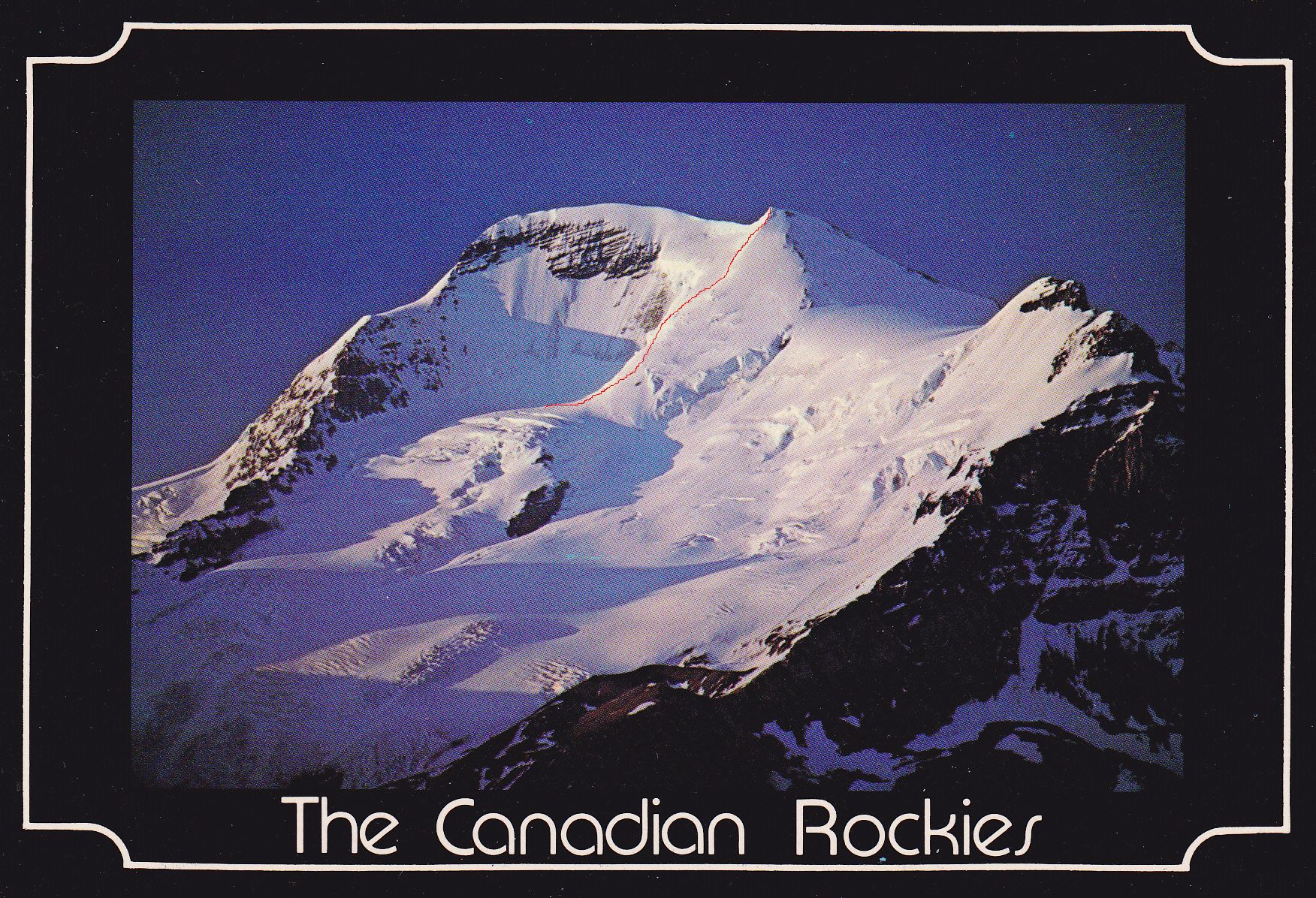

Came the 7th of July. We had moved from the Jasper area down to the Wilcox Creek campground near the Columbia Icefields the day before and we were all set to try to climb Mt. Athabasca. This is one of the most beautiful peaks in the Canadian Rockies and is a lure for many climbers. The peak stands 11,453 feet and is therefore one of that select group of 11,000-ers. There are several established routes to the top, and we thought we’d try the Silverhorn, which sits on the north side of the peak. Harry decided to stay in camp, so Brian, Scott and I headed out for an early start. Perhaps I should show you this picture sooner rather than later. It’s not one I took myself, but rather a postcard I bought while there many years ago. I use it here because it shows the route so well. I took the liberty of drawing a faint red line on the photo. It angles up to the right from the center, following the Silverhorn.

There are plenty of descriptions online, but to congeal them down for you, they say that this route should not be attempted by novices. Formal education in crevasse rescue is essential. Avalanches are also a serious risk – consider an avalanche safety training course essential.

We three got a very early start – fortunately we were in the longest days of the year, which are long indeed this far north. From where we parked, we followed a trail up the moraine, heading east-southeast to the edge of the glacier. We roped up and headed across the glacier to the base of the ridge that is the Silverhorn. It was still a chilly morning by the time we arrived at the start of the real climbing. We had already been out for a few hours by then. Something was on Brian’s mind. He said that his feet had become increasingly cold, and he felt that he should turn back at that point. We understood completely and urged him to do whatever felt right. Scott and I both knew that on a remote climb in the coldest winter ever, ten years earlier, Brian had suffered a severe frostbite injury to his feet. Ever since that climb, his feet had been more susceptible to the cold and he had to be very careful. It was obvious that he was disappointed but he was making the right decision.

The Silverhorn consists of just over 1,600 vertical feet of climbing on a 40-degree angle. It is considered to be one of the finest moderate alpine ice routes in the Canadian Rockies. Scott and I roped up with a regular climbing rope and took turns leading. We had pretty good conditions that day – it wasn’t too icy, maybe because it was still early in the season. We made it to the top of the route, which put us on the summit ridge. All we had to do was make a left turn and follow the meter-wide ridge the rest of the way to the summit. We weren’t the only ones climbing Athabasca that day. One of the others took our picture on the summit. You can see my ash-handled ice axe in the lower left. The red rope was a 9-mm rope I had for glacier travel which we used for the climb down. I wonder whatever happened to that rope? I can’t even remember the last time I saw it.

We savored the view from the top for a while, then started down. The views of surrounding peaks and of the massive Columbia Icefield were nothing short of spectacular. We descended via the Athabasca-Andromeda col route, a pretty safe bet. We tied in to the red glacier rope. There were only 2 things I remember about the climb back down. We had to choose a gully that was the lowest-angled and seemingly the safest to get down off of the ridge, and that went okay. We did have to keep an eye and an ear out for rockfall, though, as the day was heating up. Then we had to cross the glacier down below. Later in the season, this glacier is riddled with crevasses. Today, being as early in the season as it was, it was a fairly smooth blanket of snow we traveled, but we were both plenty paranoid of falling through that cover and into a crevasse. It was a gentle slope down the glacier, and at its foot we found a marked route through a band of rock. Once below this rock, we followed a trail down to its beginning at a parking area. By the time we reached our vehicle, we had been out about 12 hours on foot altogether. Climbers seem to take anywhere from 9 to 14 hours to do the climb, so I guess we didn’t do too badly. It was 8 miles and 4,800 vertical feet covered.

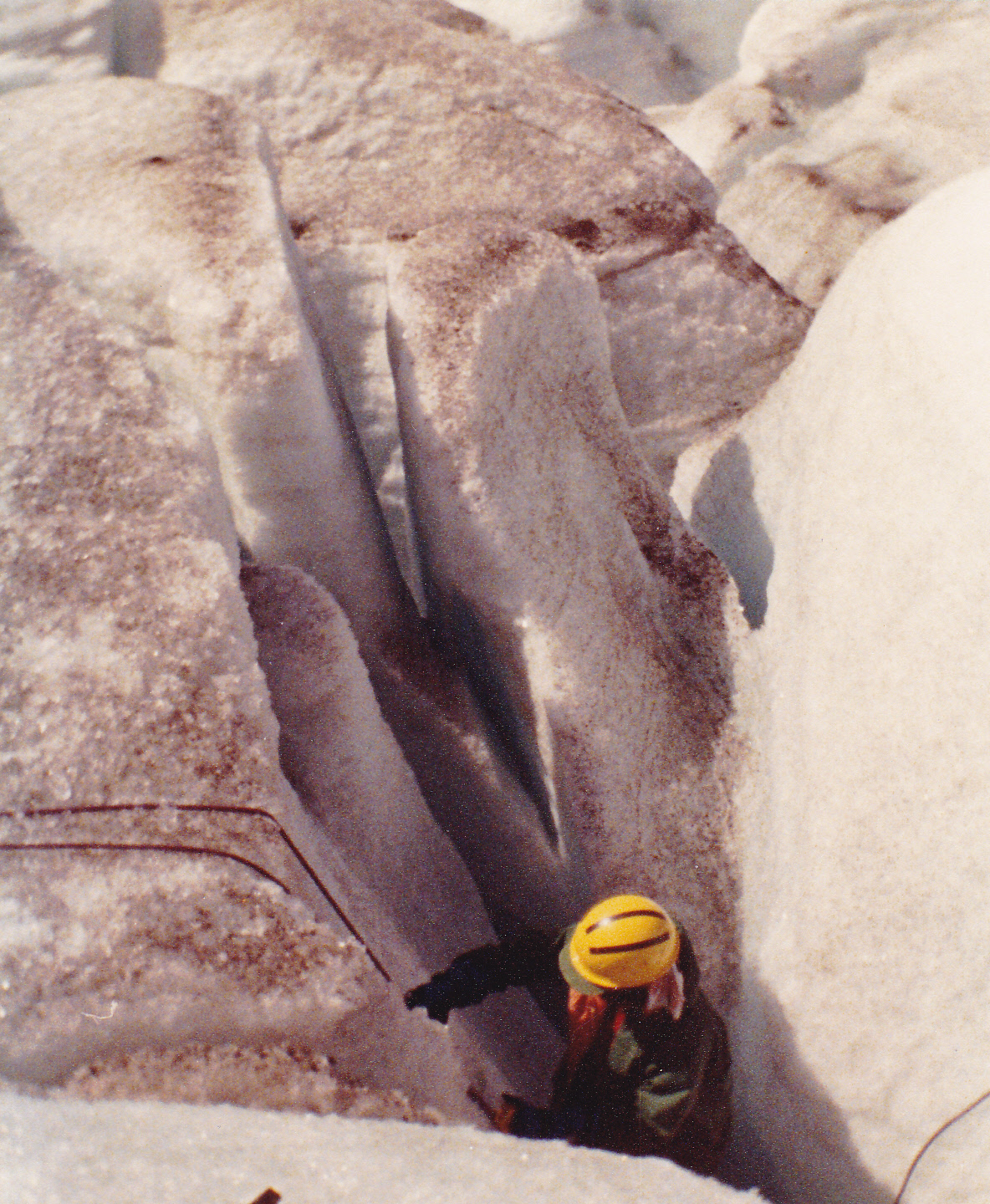

The next day, the 4 of us decided to spend the day at the nearby Athabasca Glacier. When people think of visiting the famous Columbia Icefield, this glacier is the one they see from the highway. You can park and then take a short walk over to the toe of the glacier and even climb up on to it quite easily. We decided that it was time to do some crevasse rescue practice. If climbers are attached by rope to one another and one of them breaks through a snow covering and falls into a hidden crevasse, you need to pull them up and out of the crevasse as quickly as possible. Crevasses are cold, wet and can be very deep. If you are by yourself and fall into one, it can easily be a death sentence. You’d think that one person could pull another one out of a crevasse, but it ain’t happening. Hell, I’ve been with groups where 2 of us couldn’t pull out a third, where 3 of us couldn’t pull out a fourth, where 4 of us couldn’t collectively pull out a fifth person in rescue practice. The person who fell in could be injured or unconscious and unable to participate in their own rescue. As you try to pull them up, the rope wants to cut into the lip of the crevasse. You have to secure things so they don’t slide in deeper while you get a rescue going. Rigging up a series of pulleys in the proper manner can make it easier to pull someone up and out, but that’s all in a perfect world. In reality, everything has to go exactly right. Here’s me in a shallow crevasse, healthy, conscious and quite able to climb out on my own.

A typical deep crevasse often has parallel walls, the sides of which are as slick as an ice cube, often with ice water dripping on you from above, soaking your clothes and making you hypothermic very quickly. When you fall in, you could be wedged in sideways or upside-down, and if you were wearing a full backpack you could be wedged in even tighter. No matter how you look at it, falling into a deep crevasse is a real nightmare situation. The 4 of us practiced various scenarios that day and we all concluded that our efforts were pretty pathetic – exactly the same conclusion I arrived at whenever I practiced crevasse rescue any other time and place. Here, you can read an actual account of a crevasse rescue and what was involved.

The next day, July 9th, we all headed out to climb a nearby peak together. It was an un-named subsidiary of Nigel Peak, close to the highway and of easy access. We reached a point along the northeast ridge where we were stopped by a sharp gap, leaving us 30 feet below the summit. No matter, we had a fine day and climbed about 2,700 feet for some good exercise. We spent one more day together, exploring the Athabasca Glacier, covering 6 miles and just poking around and having a good time. Something interesting happened that day while on the glacier, though. Brian and I met a younger man who told us he had recently left the US military and was doing some traveling. He introduced himself as Gregory Crouch. Nobody had heard of him then, in 1988, but he went on to become a published author and his name is well-known to serious mountaineers around the world.

One year later, in 1989, Scott died in a mountaineering accident soon after spending 10 days on Mount Robson with me and Brian. He and Brian both lived in Toronto at the time, and it was an awful shock to learn the news from Brian in a phone call. He left behind a new wife in her 20s. We had some nice climbs together, Scott, and I hope you’ve found good peaks in the hereafter.