Jumars

The peak was on one of my lists, and I knew I’d have to climb it sooner or later. Problem was, it sat out in a wilderness area, far enough from everything that it meant a backpack and at least one night out. In a magazine, I saw an article about it and was able to contact the author who had climbed it. We met, and he agreed to lead me up the thing. Was it okay if a friend joined us? – sure, no problem.

At daybreak, he led the climb, at 5.6+ with plenty of exposure. I followed and cleaned the route. I was 42 at the time, and Barbara was 60. She had decided to not follow our route – instead, was it okay if the leader would stick around long enough so she could jumar up the other side? He said fine, and set up a double rope for her. She attached a pair of jumars with webbing for her feet, one per rope.

A jumar is a device that attaches to the rope. It slides easily up, but locks itself in place so it doesn’t slide back down (unless you choose to release it). It allows you to climb straight up. Your feet rest in nylon cords attached to the jumars. The idea is that you inch your way up the rope, a bit at a time, alternating jumars. It may sound simple, but it requires a lot of energy. Barbara had to climb up 60 feet, the height of a 6-story building, most of it under an overhang with the ropes slowly spinning in thin air. It took well over an hour and, understandably, she was exhausted by the time she finished (hell, I was too, just watching her!). She had done something most people half her age wouldn’t have completed, and that’s why she’s one of my heroes.

Two Big Trips

In 1989, I traveled twice to Argentina to attempt to climb Cerro Aconcagua. Rather than booking the climb with one of those travel adventure companies that looks after every detail, I decided to arrange everything myself. The first trip, I paid for the flight, permit fees, all food and accommodations, the cost of sending my gear into base camp, in-country transport and every other little expense that came along during the 6 weeks I was in the country. The second time I went, I paid for all of those same expenses, plus ten domestic air flights within the country and all other expenses while traveling for a total of ten weeks. That included weeks of additional climbing in other places, and – oh yes, almost forgot – a successful summit climb of Aconcagua. By making all of my own arrangements and taking care of all of the details myself, I was able to do all of the above for a grand total of five thousand dollars US for both trips. Not a lot of money for such a huge amount of adventure.

Yucatán

The tropical Mexican state of Yucatán has more archaeological ruins than you can believe. It has been my good fortune to visit some of the best, the likes of Kabah, Uxmal and Chichen Itza, happy days spent roaming through ancient Mayan ruins. A few short years after I was there, some of my climber friends were traveling in the same area. They decided to visit one of the cenotes which are common in the Yucatán, to do some snorkeling. In case you’ve never seen one, a cenote is a deep, natural freshwater pit. My three friends were diving in one of them, trying to go as deep as they could before turning around and racing back to the surface. They had done this several times, each time trying to dive deeper than before. The final time, one of them didn’t come back up. My friend drowned that day, thousands of miles from home. I was shocked to learn of his untimely death, a man in his mid-twenties in the prime of life. Less than a year earlier, he and I had done a nice winter first ascent together in our BC home.

Littering

We had been many weeks traveling through Mexico. At last, the day came when we would enter Guatemala. A bus took us up to the border, then a short walk across to a waiting bus on the other side. Away we went, climbing higher into the mountains. Something was different – not wrong, but different. It didn’t take us long to figure it out. Everywhere in our thousands of miles of travel in Mexico, there was trash – along the roadsides, in the city streets, everywhere. It was as if the entire country was one big trash can. That was fifty years ago, and the same is still true today. When we crossed into Guatemala, there was a complete absence of trash. We didn’t see any along the roadways, there wasn’t any visible in the city streets – the contrast was dramatic and immediate. The same was true wherever we went during the days we spent in that country. The people were poor, but they seemed to have a lot more pride in how things looked.

Cornice

I was climbing with a partner on a peak well above tree-line. On the final stretch along the summit ridge, we were near the edge of a cornice, unroped. The dictionary defines a cornice as “an overhanging mass of hardened snow at the edge of a mountain precipice.” Hey, that’s as good a definition as you’ll find anywhere. A cornice can be a dangerous thing. Walk too close to the edge and your weight can cause it to break off, sending tons of snow hurtling into the abyss, and you along with it. Many have died in this way. Anyhow, I guess I was too close to the edge, and I punched through, but only about thigh-deep. Fortunately, the cornice didn’t break off and fall away. It scared the shit out of me, though, as, after extricating myself, I could see through the hole I’d left, down the steep mountainside below.

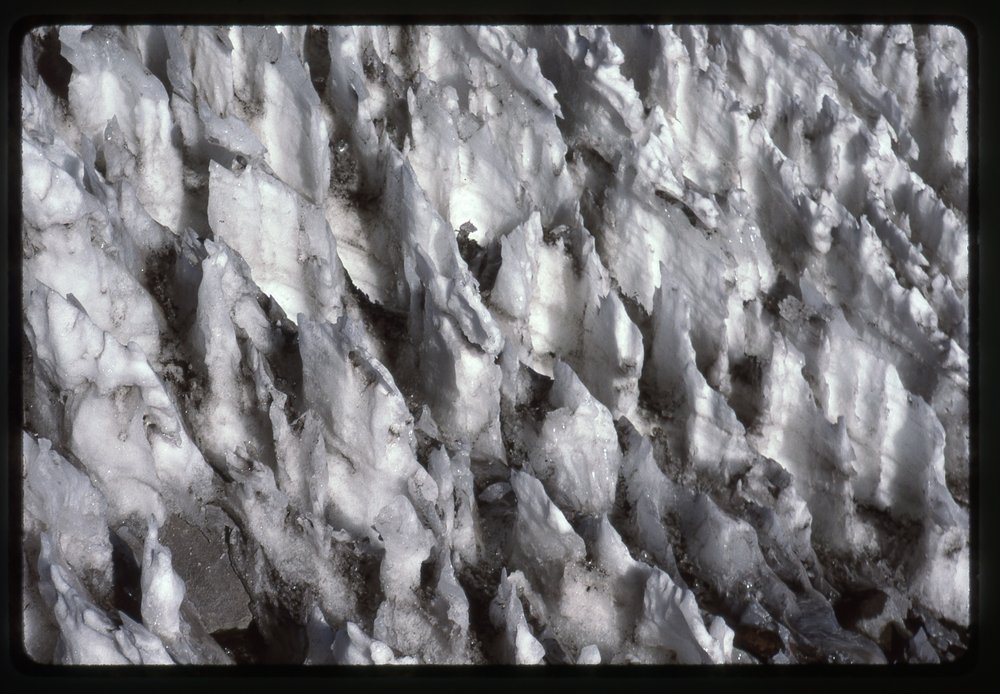

Nieves Penitentes

It’s a Spanish term, as these are common in high Andean peaks. It means penitent-shaped snows, and it refers to long, thin blades of ice or snow pointing upwards. The name comes from the resemblance to a crowd of kneeling people doing penance. They can be quite tall, as much as 15 feet. I think the first time I ever saw any was on a climb of Popo in Mexico, near the crater rim at around 17,000 feet.

Charles Darwin was the first to describe these in scientific literature way back in 1839 as he traveled a high pass from Chile into Argentina. The next time I saw them was on a climb of Orizaba, at a bit over 18,000 feet.

Apparently, the main condition needed for the ablation (where something goes directly from a solid to a gas, without first becoming a liquid) to occur to form penitentes is that the dew point must remain below freezing. That wouldn’t be hard to do on those high, dry mountains. I also saw them near the base camp on Aconcagua at around 14,000 feet.

The best ones I ever saw, though, were on Parinacota volcano in Chile. Brian Rundle and I had to go through a huge field of these to climb the peak. These were about 2 feet tall. You can tell by looking at them how tiring it would be to climb steeply up through them. You had to be really careful, too, as they were rock-hard ice and really sharp. You could twist an ankle, or get punctured by one. These were up pretty high, somewhere between 18,000 and 19,000 feet.

Here’s a fascinating bit of trivia for you. Astronomers think that there are penitentes up to 50 feet tall in the tropics zone of Europa, one of the moons of Jupiter. NASA says that the New Horizons spacecraft has discovered penitentes in the Tartarus Dorsa region of Pluto – pretty cool stuff, right?

Platform

We had been at it all day, or at least what passes for a day at 18 degrees south latitude in the dead of winter. Once it became apparent we were going to lose the light, we called a halt. There was nothing in sight that could even remotely pass for a decent spot to pitch a tent, so we had to create one. It’s not as if the 2-man North Face required a lot of room, but it did require at least something. We had an entire mountainside of rough lava chunks to work with, thankfully. I don’t recall how long it took, but we cobbled enough of them together to end up with a serviceable platform, big enough but nothing more. We were on the Chilean side of the border, with Bolivia a mile away, but nothing would disturb our slumbers there at 17,000 feet in the frigid night air.

Copacabana

If you ever get a chance to visit Lake Titicaca, do it. And if you do, consider yourself fortunate if you can spend a while at the lakeside town of Copacabana. What a delightful place, on the Bolivian shore at 12,600 feet elevation. As evening came on, Brian and I found ourselves in a little place called the Puerta del Sol restaurant, settling in with a real international group – British, Dutch, German, Turkish, Canadian and American. A more fun group you’d be hard-pressed to find. We had a terrific meal of trout (the lake is famous for them) and good Bolivian beer, all for a price that was so low they should have put us in jail. After that, we all strolled through the quiet streets looking for a nightcap to finish off what had been a perfect day. Good memories.

Snakes

Living in Arizona brings a different twist to life – snakes. We have so many different kinds here, but I wanted to tell you a bit about just the poisonous ones. We have 15 different species of rattlesnakes alone, as well as 2 species of coral snakes and 8 other species that are poisonous. Rattlesnake venom is both neurotoxic and hemotoxic.

Neurotoxins destroy nerve tissue, meaning that your body can’t function properly, while hemotoxins cause necrosis (tissue death) and disrupt blood clotting. The effects of rattlesnake venom include the following:

*Difficulty breathing. You start by finding it difficult to draw deep breaths. If the impact is severe, you find it difficult to breathe at all. That’s because the nervous system is damaged, so your brain can’t tell your lungs to keep breathing. *Tissue death. The tissue around the bite mark will start to turn black and die. You may need to get your limb amputated to prevent the necrosis from spreading. *Nausea. You may feel a strong urge to vomit. *Dizziness and trouble balancing.

Every year, some Arizonans are bitten and require treatment. Fortunately, antivenoms are available, but they are hellaciously expensive – having to pay for them out of your own pocket will bankrupt you. Most snakes are inactive during the cooler winter months, but once the weather warms up, we need to be more aware of them so we don’t end up on the evening news.

Sewing-machine Leg

Most climbers who climb on rock have experienced something we call “sewing-machine leg”. It’s called that because when it happens, the lower leg goes up and down quickly in a motion much like that seen when using an old-fashioned treadle type of sewing machine, like an old Singer model. I was curious as to the exact reason for this, and found this description online, which I think explains it perfectly.

Particularly during rock climbing, the calf muscle is under constant demand to perform in carrying someone’s weight. During normal walking, there is a rest/contraction cycle during which the muscle contracts to propel the person forward. This is done alternately by both legs, giving a moment of rest and relaxation to the opposite leg. These phases are called push-off and swing-thru. The push-off phase causes the muscle to contract, the swing-thru phase causes the muscle to relax. When alternation of contraction and relaxation are not possible, the muscle fatigues quickly and responds with a cramp-like action, causing the foot to go up and down rapidly. Pushing the heel down breaks up the spastic contraction and lengthens the muscle so it can contract (shorten) again later in the cycle.