Bears

Here in Arizona, contrary to what a lot of people may believe, we have a lot of forested country – it’s not all sand and desolation. In fact, the largest ponderosa pine forest in the world is here. Our forested land is home to a lot of black bears, but in the 37 years I’ve climbed here in Arizona, only once have I seen bears. On a fine day in late August, Paul and I were sitting atop Mount Graham eating lunch when a mother bear with 2 cubs in tow came bustling past. That was it, the only time I’ve seen bears in Arizona.

However, during my first 20 years of climbing, I lived in British Columbia. So much wilderness, so many bears. Over the years, I came face-to-face with an average of 3 bears each year while out climbing. One time, I even met a mother grizzly with her 2 cubs. In all of those encounters, I never had a problem – none of the bears was aggressive towards me. Most of them took off running away from me as fast as they could, seeming more afraid of me than I was of them. Only a few ever stood their ground, and I always give them a wide berth.

Lost For A While

The first mountain I ever climbed was a few miles north of the town where I lived during high school. I liked it enough that I went back several times, enough that I talked several of my school chums into going with me one weekend. We had all gone up the old logging road to the lake nestled in a basin near the top, fooled around there for a while, then started back down. As we descended the road, one of the younger guys decided he’d go down through the old-growth forest instead, but stay within shouting distance of the rest of us. Well, you guessed it – we soon lost contact with him. Even with all of us shouting his name, there was no response. By then, we started to panic. What had happened? Was he hurt, had he fallen off a cliff, or had he moved away from the road far enough that he was deep in the forest and lost? We all kept moving generally downhill, either on the road or in the forest near it, and shouting ourselves hoarse. By then, we were all thinking that this could get serious and the shit would certainly hit the fan if we had to call the police when we got back to town. Fortunately, lower down the mountain, our lost boy stumbled out of the bush and back on to the road, where we met up with him. He (and we) had dodged a bullet, and we all felt much relieved as we rode our bicycles the several miles back to town.

Death Near the Border

Jake was out ahead of me and around a corner in the brush. I heard him call out “You’d better come have a look at this”. When I reached him, it was obvious what he was pointing at. The white thing was a human skull. This picture shows where it sat. That’s not a road it’s on, but a watercourse we call a wash, where water can run after a heavy rain. We looked around, but found no other bones. They could have been scattered by animals, or time and the elements might have done the same. We were only a mile from the Mexican border. Sadly, whoever this border-crosser was, their journey north into the U.S. had ended after it had barely begun. We marked the location with GPS and later reported it to authorities.

It was an eventful morning, to say the least. Not an hour earlier, we had encountered a group of desert bighorn sheep. Shortly after coming across the skull, we discovered a previously-unknown stand of Senita cactus, one of the rarest in the country.

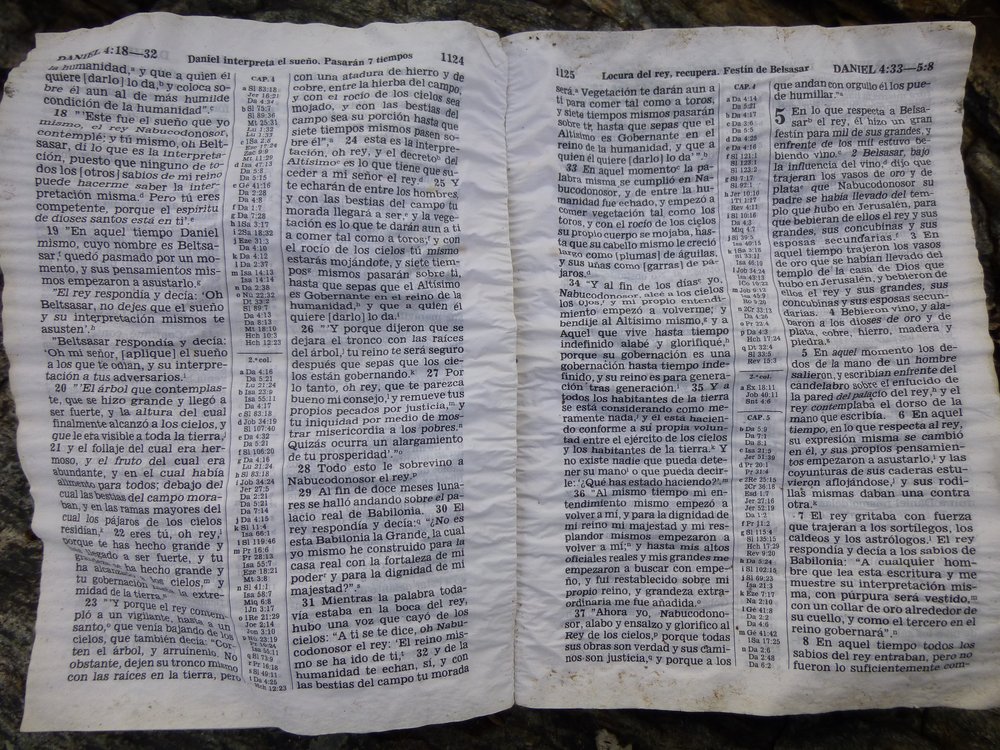

Spanish Bible

It was a sultry morning about 10 years ago when I found myself atop a peak in the White Hills. Not expecting to find any signs of a previous visit, imagine my surprise when I found the things I did. An empty bottle of hot sauce, a food wrapper, a pair of shoes with a huge hole through one of the soles, and this:

It was a Spanish-language bible, quite intact in spite of the elements. As I sat there, I tried to put myself in the place of the one who had left it. Their shoes had worn out, and unless they had a spare pair, they’d soon be in a world of hurt. The desert is just not the kind of place where you can walk barefoot, for so many reasons – I cringe just thinking about it. They had carried that bible so far – obviously they were a person of faith, and I hope it had given them the strength to continue, but it must have been a heart-wrenching decision for them to leave behind such a prized possession.

Buried

Paul and I were heading into a remote piece of desert, deep into the hot zone of the bombing range where no one was allowed to go, ever. Indocumentados and those working for the drug cartels passed this way on foot, however, and the truck would be a prime target, if discovered, for them to steal. It was decided that although it may be hard to hide an entire truck, we could take steps to disable it. Paul removed a small but crucial electronic component which we’d take with us during our week of climbing. But there was a lot else that we didn’t want them to take, yet we needed to leave with the truck. Emergency food, spare clothes, life-saving water, truck tools. Some of it we bagged up and sealed well. A series of holes would take it all, and that’s how we prepared for our departure. Have a look at this – I think you’ll get the picture.

We even dug a hole and buried the shovel. The reason we buried all of the truck gear was that a primitive road nearby had been created by Bad Guys, who did in fact drive through the area in stolen vehicles from time to time – they’d love nothing more than to get their hands on all our stuff. Our plan worked. After a week of climbing, we were back to this spot and everything was exactly as we had left it.

Unexpected Visitor

Jake and I were settling in to our remote desert campsite. Just as it was getting dark, he called out to me and I saw he was pointing to a man a hundred feet away. He approached us and was calling out “comida”, the Spanish word for “food”. He was Hispanic, mid-20s, slightly built, dressed in camouflage shirt and pants, camo wide-brimmed hat, brown shoes. He had no backpack, only the clothes on his back, and a black plastic water jug.

We were concerned that others in his party could be lurking nearby and cause us trouble. I questioned him, and he said his companions had been apprehended by the Border Patrol several days earlier. Just the same, we didn’t want him sticking around. I gave him some food, and he took out a wallet and offered me some U.S. cash, which I refused. He said he had water. He said his goal was to reach Phoenix, still a hundred miles distant. We pointed him in the right direction and told him that if he traveled steadily, he could reach the Interstate by morning. He said that he traveled by night anyway, so he was pleased to hear that.

How he could do that on a moonless night was amazing to us. The land was creased by countless gullies and studded with an infinite number of cacti which could cause you no end of pain. Jake and I were astonished that he or anyone else could travel safely in this unforgiving land in such inky blackness – we knew that we couldn’t do it. We sent Luis off with a “Vaya con Dios” and he vanished into the night.

Valley of the Moon

Not 20 miles from Tucson lies the Rincon Mountain Wilderness Area, and out in that wilderness sits an un-named peak that attracts no attention whatsoever. Well, almost no attention – three people have been foolish enough to make the effort to climb it. To reach the peak entails a world-class bushwhack, no matter how you approach it. Miles of bushwhacking and thousands of vertical feet of the most soul-destroying brush you can imagine. Actually, I take that back, because there is no way you can imagine the horror involved unless you’ve actually done it.

The peak sits at the very upper end of something called Valley of the Moon. It’s a small feature, barely half a mile square. lying between 6,800 and 7,300 vertical feet above sea level. I’m unable to determine the origin of the name, but I just think it is very cool. And unless you’re as much a glutton for punishment as the 3 of us fools who have actually gone there, you’re never going to know what it’s like to visit Valley of the Moon.

.50 Caliber

Once the United States entered WWII, munitions plants started cranking out bullets for the Browning M2 machine gun, the most widely-used weapon on the American bomber and fighter planes. Untold millions were manufactured, and planes like the P-51 Mustang gobbled them up. Pilots needed to practice shooting, and the perfect place to do that was here in the Arizona desert. The Barry M. Goldwater Range is a vast, 1.9 million acre tract of land used by 3 different military bases. Even today, you can walk through the range and find spent shell casings lying on the ground. I’ve been in places out there where there were so many, gathering them all up was just too much brass to carry. Here’s a good website that will tell you all about them. I never get tired of picking them up and figuring out the year and plant of their manufacture.

Woollen Delays

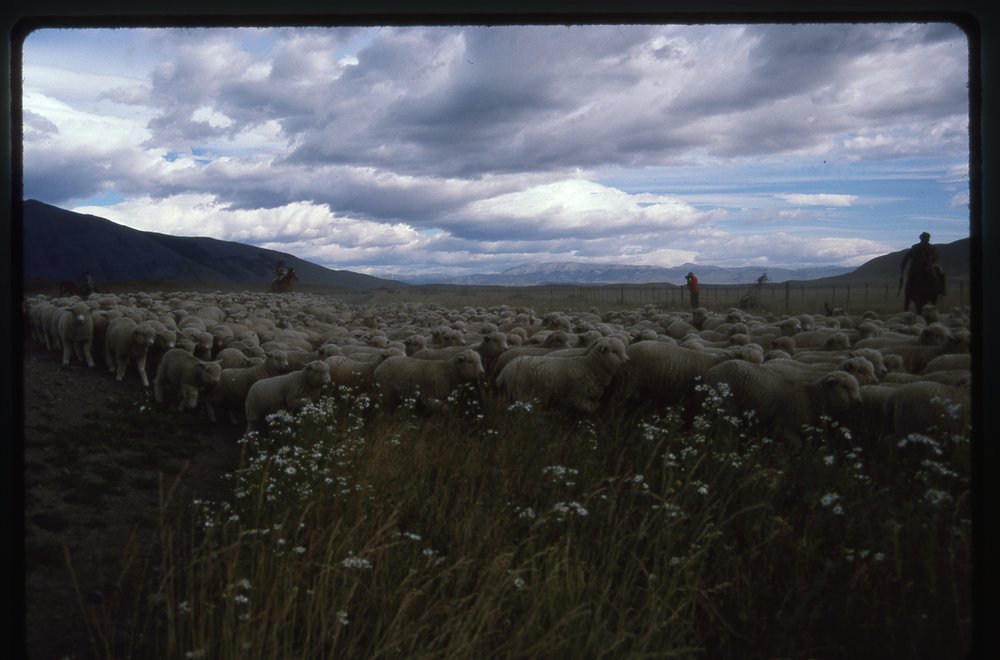

There are places in the world where people grow a lot of sheep, and in those places sheep may have the right-of-way. Here’s a for-instance. One time when I was traveling in the Chilean part of Patagonia, our vehicle came to a dead stop along the highway. The reason – sheep, lots of them, were being herded (is that even the right word for sheep?) and they happened to be on the road. There’s nothing that can be done to speed them up. The men on horseback were trying their best to keep them moving.

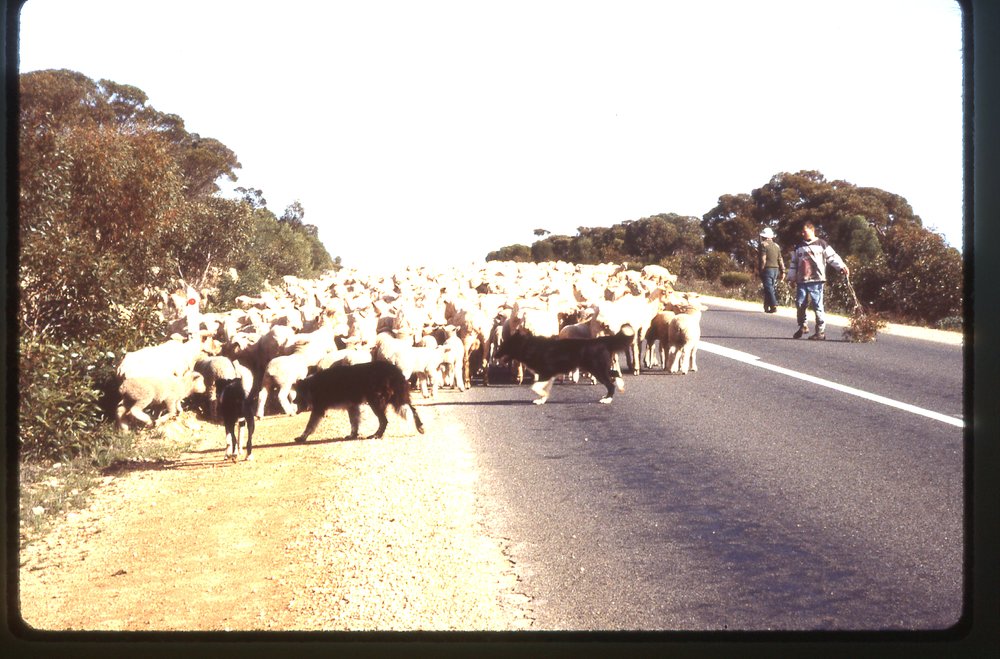

The same thing happened when I was in the state of Victoria in Australia, except here the men were on foot and were using dogs to keep the sheep moving. In this case, it took 45 minutes to maneuver them to a point where they were no longer blocking the highway.

I saw the same thing going on when I was in New Zealand, where there are far more sheep than people (26 million versus 5 million). There are other countries where sheep have the right-of-way, and understandably so, as they form an important part of those economies.

Hoping For Water

I have gone on extended backpacking trips in the desert where I have depended on finding water. Sometimes there were what are called “guzzlers” or water catchments that I was hoping to find, and these were usually reliable. They are built to provide water for animals, to sustain a population of bighorn sheep or deer, but many other animals use them. The water doesn’t look like much, but it can save your life. You will need to filter out the bugs and possibly purify it, but it does the job. This picture shows what is typical – rainwater is stored in an underground tank so it won’t evaporate, then gravity feeds it into a concrete trough called a “drinker” for easy access by animals. Many are the times I’ve filled my bottle from one of these, and happily so.