I’itoi

Only a few miles to the west of Tucson lies the Tohono O’odham Indian Reservation. This land is the home of the O’odham people, who have lived there for centuries. In a few places on the map can be found names which reflect their beliefs. I’itoi is the name of their creator god, which is sometimes spelled Iitoi. We can find the name on the western edge of the reservation on a spectacular peak known as I’itoi Mo’o or I’itoi’s Head. In another location, quite close to the administrative capital of the reservation, we find the name Etoi Ki on a small peak. This is the anglicized version of the O’odham name I’itoi Ki, which means “House of I’itoi”. I’d like to share with you here the words of an O’odham storyteller which nicely sums up their creation legend.

The world was made by Earth-maker out of the dirt and sweat which he scraped from his skin… the flat earth met the sky with a crash like that of falling rocks, and from the two was born Iitoi, the protector of Papagos. He had light hair and a beard. Iitoi and Earth-maker shaped and peopled the new world, and they were followed everywhere by Coyote who came to life uncreated and began immediately to poke his nose into everything. In this new world there was a flood, and the three agreed before they took refuge that the one of them who should emerge first after the subsidence of the waters should be their leader and have the title of Elder Brother. It was Earth-maker, the creator, who came forth first, and Iitoi next, but Iitoi insisted on the title and took it. Iitoi brought the people up like children and taught them their arts, but in the end he became unkind and they killed him. But Iitoi, though killed, had so much power that he came to life again. Then he invented war. He decided to sweep the earth of the people he had made. He needed an army and for this purpose he went underground and brought up the Papagos. They live in a land scattered with imposing ruins which belonged to the Hohokum, “the people who are gone”. Iitoi drove them, some to the north and some to the south. Iitoi had a song for everything. Though his men did the fighting, Iitoi confirmed their efforts by singing the enemy into blindness and helplessness. Iitoi has retired from the world and lives, a little old man, in a mountain cave. Or, perhaps he has gone underground.

The term Papago was formerly used as the name of the O’odham. The Hohokam are considered to be the ancestors of the O’odham people.

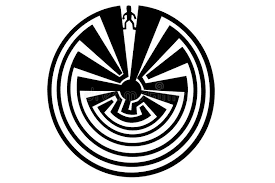

I’itoi is most often referred to as the Man in the Maze, a reference to a design appearing on O’odham basketry and petroglyphs. This positions him at the entrance to a labyrinth. This labyrinth is believed by the Tohono O’odham to be the maze of life, where a person travels through life and encounters the different moments that impact them.

There is a place on the reservation, near Baboquiviri Canyon, where, high on a mountainside, many hundreds of feet above the desert floor, can be found a cave. It is regarded by the O’odham as the dwelling-place of I’itoi, and is a place of pilgrimage for the people. I would like to visit that cave some day and pay my respects.

Tortoise Banana

Many years ago I was driving north from Sells along an old, tired road into the South Comobabi Mountains. I reached a point where the road was completely washed out, so I parked and started on foot. No sooner had I begun when I had a rare treat – a desert tortoise was walking on the road ahead of me. These are special creatures, capable of living as long as 80 years. They can go an entire year without drinking any liquid water, instead getting the moisture they need from the food they eat. Wondering if I could do anything to help out this little guy, I looked in my pack, where I found a banana which I could certainly do without. I knew they ate cactus fruit when they could find it, so it seemed like a fresh banana might not be too much of a stretch. I peeled it, and set it on the ground right in front of him. I didn’t stick around, not wanting to alarm him any more than necessary. After I walked to the road’s end near the old Emperor and Duchess Mine, I climbed 2 mountains, then returned along the road. I found the exact spot where I had met the tortoise, and guess what? He was no longer there, having moved on, and there was no trace of the banana – he had eaten every speck! Obviously he liked it, and hopefully all that moisture in it helped him out.

Devil’s Thumb

There is a striking mountain on the edge of the Stikine Icecap known as Taalkhunaxhkʼu Shaa in the native Tlingit language, and we know it as Devil’s Thumb in English. The Tlingit name means “the mountain that never flooded” and is said to have been a refuge for people during Aangalakhu, “The Great Flood”. It is one of the peaks that mark the International Boundary, and is shown on some maps as Boundary Peak 71. Surprisingly, the summit is only 29 miles northeast of the town of Petersburg, Alaska.

The first ascent of the 9,077-foot peak was done in 1946 by its east ridge. Fred Beckey and 2 friends made that climb, and their ascent was regarded as a route that combined technical difficulty equal to anything ever climbed on the continent to that time, with great remoteness and terrible weather conditions. That route has been repeated a few times since then, but what makes the mountain famous is not what has been done there but, rather, what has not been done. I’m talking about the Northwest Face.

Rising 6,700 ft (2,042 m) from the Witches Cauldron at its base to the summit, at an average angle of 67 degrees, this is the biggest rock face in North America. The conditions prevalent also make it perhaps the most dangerous climb on the continent. The Northwest Face has seen many attempts; at least three teams have died on this face. It stands as a huge wall with bad weather, bad rock, bad ice, and bad avalanches. “It is a dangerous and difficult face that rarely, if ever, comes into condition,” says Dieter Klose, who in 1982 made it halfway up the route, higher than anybody else alive.

When I say three parties have died on this face, I mean that they vanished without a trace – wiped clean from the face as if they never existed. Their bodies have never been found. The world’s best rock climbers and alpinists seem to be steering clear of the face in recent years. That’s smart – you’d have to have a death wish to attempt it. I’d love to see someone climb it in my lifetime, but I won’t hold my breath until that happens. A party which climbs the face and lives to tell about it will shock the entire climbing world – word would flash across the globe immediately.

False Summits

Every mountaineer has had the experience of climbing a peak, only to find that what they thought was the summit was in fact an illusion. You walk the final steps to what you thought was the highest spot, and then see a higher point farther away. That spot might be an easy stroll along a ridge of rock or snow, or it could pose quite a challenge. There could be serious obstacles separating you from the “new” high point. There are plenty of peaks out there where there is a series of false summits – sometimes it’s impossible to see all the way to the very highest point, and you just have to keep going over each one until you know for sure you’ve arrived. If visibility is poor, due to clouds or falling snow, it can be a challenge to know you’ve reached the highest point. Sometimes bumps competing for the title might be so close in elevation to each other that you may need to use a sight level to help you determine the winner. Even then, there might be no clear winner. Many are the peaks where there’s no substitute for actually setting foot on every contender, to say for sure you’ve climbed to the highest point.

Praying For Water

We wanted to climb some peaks out on the bombing range, where, of course it was forbidden to go. Nobody could get permission, ever, to go where we were headed. It was so out there that 2 friends who thought about joining us chickened out at the last moment – the adventure was too rich for their blood. We set out under cover of darkness an hour after sunset on mountain bikes, finding our way by climber’s headlamp. The journey started on a paved road, which soon degenerated into a broken mess – we were almost better off riding on the dirt off to the side. Some miles later, near a military observation tower, we turned off on to a dirt road and continued miles more until we reached a large, sandy wash where we stopped for the night.

At daybreak we started again, stopping a mile later to stash some water amongst the rocks on a hillside. Continuing, some miles later we buried a container of water under the sand in a tributary of Midway Wash. These 2 caches were for use on the way back out after our climbing was done, as we knew we’d desperately need them by then. What semblance of a road we’d been following soon disappeared as we continued north, the desert having reclaimed it completely. My God, those next miles were hard miles, seeming to never end. We stopped often to check the GPS and plot our position on the map.

Finally, hours later, we encountered a road which we could follow – it headed in the direction we needed. Getting this far had consumed more of our remaining water than we’d hoped, and our supply was desperately low. We still had a peak to climb and a night to camp out, and knew what water we had wouldn’t be enough. Hoping against hope, we covered a last couple of miles, praying that we might find some water at a rumored source in a canyon. If there was none, it was going to be a grim next 24 hours until we could make it all the way back out to our last cache. We had ditched the bikes and were now on foot. As we came around a corner, we spotted something ahead – was that water? There, on the canyon floor, was a small puddle, maybe a quart of dirty water. We kept going, and found another bigger puddle, then another and another. In all, a series of seven puddles, some of them holding a couple of gallons – we were saved! It was all we needed, and more. You should have seen the big shit-eating grins on our faces as we filled our bottles to the brim. We felt rich indeed.

Hummingbird Ridge

One of the most difficult climbs in North America has to be Mount Logan, Canada’s highest peak, tucked into the southwest corner of the Yukon. Nearly all those who attempt it use the King’s Trench route, which is considered the easiest route to the summit. Even so, it is a very challenging climb, and many who try do not succeed. There are many other possible routes on the mountain, but there is one that is legendary. The Hummingbird Ridge has been attempted several times, but only successfully climbed one time, way back in 1965. Every attempt on that route since has failed – in fact, nobody has come even close to completing it. It is so daunting, so difficult, so dangerous, that it is rarely attempted. It’s another of those climbs that, if the route is successfully repeated, it will send shock waves throughout the world of mountaineering.