Test Pattern

Young kids nowadays won’t believe much of what I am about to discuss, but honest, all of this is true. If you are of a certain age, you’ll remember these things like I do. First of all, television stations didn’t broadcast for 24 hours a day like they do now. They would sign off and all shows would stop at around 11 PM or midnight (it just depended on the channel, the network, and maybe how big their audience was). Once the shows were finished, they would usually play the national anthem (the Star-Spangled Banner here in the States, or God Save the Queen where I grew up in Canada), and then you would see what was called the Test Pattern. For most stations, it looked like this, shown below. It didn’t have all those words on it, but I found one that had all those printed explanations on it – who knew? All those bits and pieces of the test pattern were for a purpose, but it seems to me that all of that would only make sense to an electronics wizard.

How well I remember that test pattern, though, with the Indian chief – they used the same one in Canada. That’s what you would see on each channel all night long, until they resumed broadcasting shows at 5 or 6 in the morning.

Watching television back in the day was much more of an adventure. Often the set just had what were called rabbit ears to pick up the signal. This was long before cable.

You had to fiddle with these. They swiveled around, and could be adjusted to be longer or shorter. Countless hours could be spent playing with them to try to get the clearest possible picture. If you were lucky enough to pick up the signal from more than one channel, you might have to adjust them differently for each channel. Some people swore that putting a wad of aluminum foil on the tips could improve reception, while others felt they got their best signal if somebody stood there and held the ends.

And that wasn’t all you had to do. Back in those days of analog TV signals (rather than the digital we use today), television sets had more things you had to fiddle with. They usually had separate knobs to adjust the picture vertically and horizontally. Others were to adjust the contrast, and even fine tuning. Watching TV back then was a real adventure requiring personal involvement.

Uncle’s Land

Way back in the 1970s, I lived in a small town in Canada. Trying to be a good hippie, I envisioned myself living off the land and being as self-sufficient as possible. Not that I was having much luck doing that, but I tried to do what I could. I would pick wild berries, pick nuts (filberts and walnuts grew well in the area and there was the odd tree on vacant land if you knew where to look), and generally try to find and harvest wild things that could be useful. One day I wandered through an open field, a couple of acres on the edge of town and discovered wild peppermint growing there. It was vacant land with no home nearby, the mint was abundant and I was excited to see how much of it there was. I went back home to get a few paper shopping bags, then returned to begin my harvest. I hadn’t been there long before a vehicle pulled up and parked behind mine. Uh-oh, maybe I was in trouble. Imagine my surprise when the man who approached me turned out to be my favorite uncle who lived in the same town. I think we were both relieved to see each other, and Uncle Bob told me that I was welcome to pick as much of the mint as I wanted, a happy ending indeed.

Thick Air

I had spent a lot of time on a big mountain in South America, much of it up really high. In only 2 days, I was all the way off the mountain and had returned to the city. I felt drunk with the oxygen-rich air, savoring every lungful. The best way I could describe it was that it felt thick and nourishing. I suppose that would be accurate, as from the summit back down to the city, I had dropped a whopping 20,000 feet in elevation in just 2 days.

Slide Rule

When I was a university student, they hadn’t yet invented hand-held calculators. What we wouldn’t have given to have had one, though. Instead, you calculated everything longhand on paper, or you used a slide rule. Have a look at the link, and it’ll tell you everything you’d ever want to know about those devices. They worked well for multiplication and division, and for roots, exponents, logarithms and trigonometry, but not so well for addition and subtraction. Every student of the sciences seemed to have one in the 1960s, but by the 70s, handheld calculators were coming into their own, and as they became cheaper, the slide rule went the way of the dinosaur.

Clumsy

The first time I tried to climb Aconcagua, the highest mountain in the Andes, I was stuck for 5 days and nights at a place known as Berlin Camp. This place is high, about the same elevation as the top of Mount Logan. The weather was pure crap for the whole time I was at that spot. There are 3 tiny wooden huts there. One of them has part of its roof missing and is no longer useable. Another is really small, suitable for one person to comfortably sleep inside. The third one is bigger and is in good shape, at least it was when I was there over 30 years ago. During those stormy days, a few of us would congregate inside that third hut and pass the time, swapping lies and trying to stay warm. It was a good place to melt snow and cook food.

While I was there, so was an Englishman who shall go un-named. This guy was the clumsiest bastard you’ve ever met. We would sit on the wooden floor around 1 or 2 mountaineering stoves going full-bore. They were almost constantly melting snow to produce water for drinking, and some of the time we’d be cooking food. I lost track of the number of times that this guy would accidentally stick his leg out, while wearing his big mountaineering boots, and kick a stove and knock it over, spilling the precious contents out on to the floor. We became so pissed off at him that we threatened to toss him out into the storm and banish him back to his tent. All of us climbers have been in a situation where, tent-bound, somebody has spilled a pot of precious water or food, so we can relate to that happening. But to happen over and over, that was unforgiveable.

Nursery Rhymes

Your brain can become so addled when at high altitude and suffering from acute mountain sickness that, it has been said, you can’t even properly recite nursery rhymes you’ve known since childhood. It’s true, I’ve seen it happen.

Military Aircraft

Back in 1991, I was climbing in Argentina. Actually, during a brief lull in that climbing, I made my way south. One day, I found myself in the city of RÍo Grande on the island of Tierra Del Fuego. That was where I had to change planes to continue south. A modern jet aircraft had brought me that far from Buenos Aires, but then I had to change planes. For some reason, the jet wasn’t going any farther. I got on the next plane, but was surprised to see it was an old Argentine Air Force aircraft. It could seat probably 30 or 40 passengers, and it had two large propellers. We finally took off, and climbed from sea level to probably 5,000 or 6,000 feet, because we had to pass over peaks that were something over 4,000 feet in elevation. Planes drop precipitously after that to land in Ushuaia, the world’s southernmost city, also at sea level. We made it just fine, but it sure was an exhilarating flight in that noisy Fokker.

Mule Assist

After a week of climbing up high, to 17,400 feet on the best of those days, I was back at my base at around 10,000 feet. A group of Argentine army soldiers were taking mules up high into the range. They offered me a ride. I grabbed the chance, and they took me up to about 14,000 feet, where they dropped me and my huge pack. It had required no effort to get that far, but as soon as I shouldered my heavy pack, it felt like it weighed a ton. I had to climb up to 15,185 feet to a spot where I wanted to camp, and that thousand-plus feet felt like a lot more. I was totally shagged out by the time I arrived.

Farthest Road

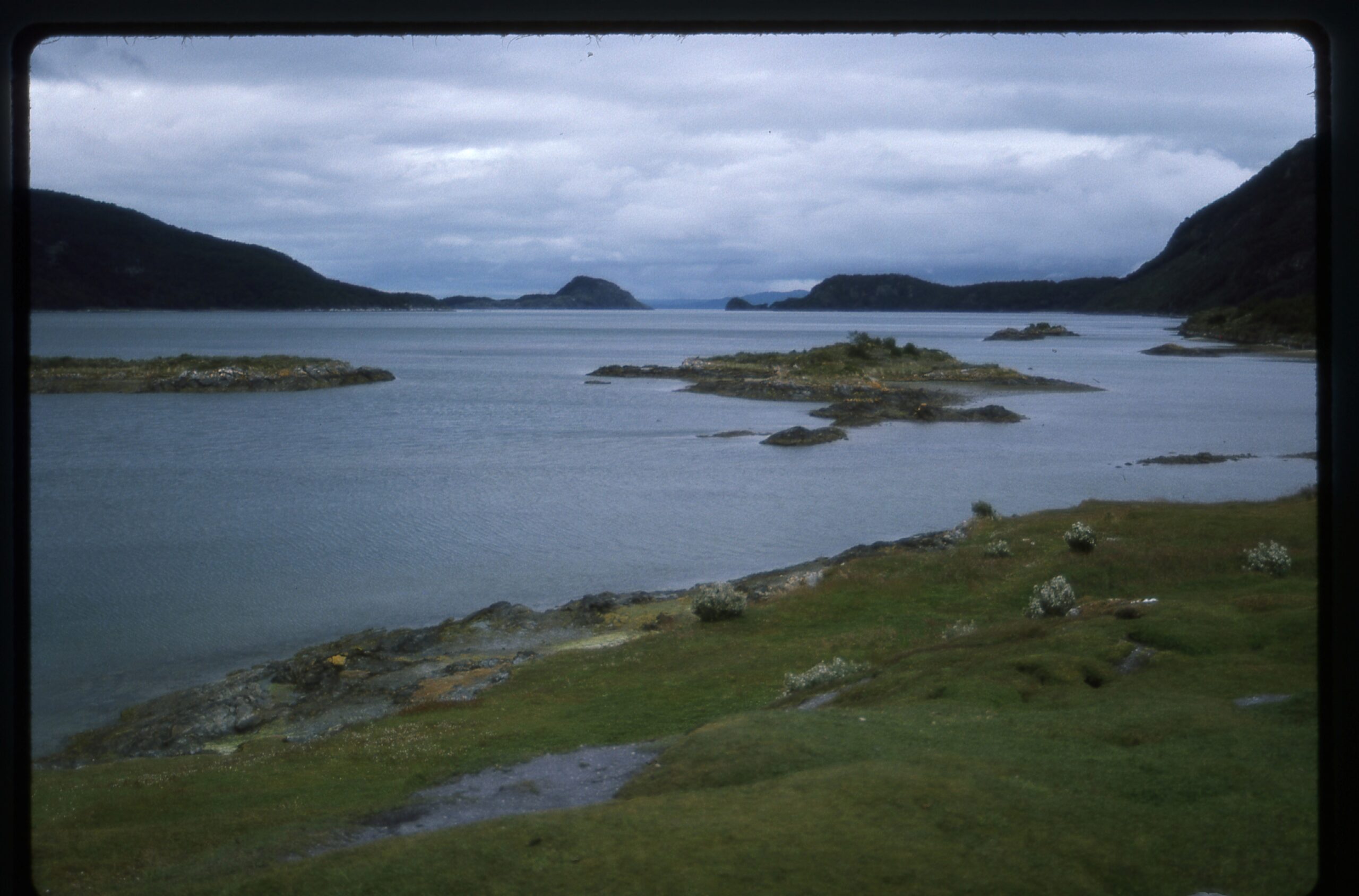

It is said that the farthest point south to which you can drive on Planet Earth is in Tierra del Fuego National Park in Argentina. Highway 3 officially ends at the shore of Beagle Channel at Bahía Lapataia. This is the end of the Pan-Amercan Highway, and it is 3,045 KM by road south of Buenos Aires. I took this picture when I was there in January of 1991. It is only a few kilometers west of the city of Ushuaia. The road ends at 54º 50′ south latitude.

Night Driving

We were driving south through California, and the hottest weather we had encountered so far was 100° near Merced. A night spent at Tioga Pass was much cooler, at 9,943 feet. After a comfortable day at Yosemite, we moved on and soon found ourselves down in the oven that was Fresno. Man, it was 104 degrees! For a couple of guys from Vancouver, it felt like an oven. Neither of us had ever experienced such heat in our lives. We decided to travel at night to minimize the misery. It worked okay for a day or two, but once we crossed the border into Sonora, it became apparent that since it was monsoon season and we were in the desert, it was going to be bloody hot no matter what we did. Dan’s car didn’t have air conditioning, so we really paid our dues over the next 3 weeks.

Morse Code

When I was a kid and in Boy Scouts, one of the scoutmasters asked if any of us would like to learn morse code. I was one of a group who said yes, and we spent some months learning to send and receive code using real morse code keys. It was challenging fun and we actually got pretty good at it.

Decades later, I was climbing a mountain in Arizona in a snowstorm with friend Dave Jurasevich. He had a small 2-meter hand-held radio with him, and I was impressed to watch him carry on a conversation with a fellow a hundred miles away. So impressed, in fact, that I decided then and there to study for my ham radio license so I could use such a radio myself. Back then, to get the introductory level of license, you had to pass a written test and also be able to use morse code up to 5 words per minute. Well, I studied for the written test, and practiced enough to also pass the morse code part of the test, thus earning the lowest level of license. The next higher levels of license required being proficient with morse code at a higher speed. I practiced endlessly, which you could do on a computer, but try as I might I couldn’t get beyond 8 words per minute. Then one day the FCC removed the morse code requirement for those higher levels of license. I jumped at the opportunity before they changed their minds – all I had to do was pass written tests.

I studied for the General license – it was a multiple-choice test, and they supplied a book with the pool of questions. Well, I do pretty well on multiple-choice, and I passed it fairly easily. That done, there was only one higher level of license I could go for. The test would be comprised of questions from a huge pool of over 700 questions, some of them dealing with some tricky math. I studied hard and aced the test and earned my Amateur Extra Class license, but if they hadn’t removed the morse code requirement, there’s no way I would have ever earned those higher licenses.