Please be sure to read the previous chapters in this story before starting in on this one.

Those who had chosen to camp overnight at Pléneau Island were gathered up by the expedition crew and were all back on board by 5:00 AM this morning. I noticed that in the nearby waters was another ship.

They must have been waiting for us to leave so they could have their turn to land on Pléneau Island. I could barely make out the name of the ship, the Polar Pioneer. She was Finnish-built in 1982 and nowadays operates out of Scandinavia. Built for rugged ice conditions, she only holds 48 passengers – nice and intimate.

It was only 6:20 AM, when I took the above photos, so we were getting an early start. The captain had announced the night before that we would be doing something special today, and for the best views we should head up to the observation deck by 6:30 or so. We were to travel through the Lemaire Channel, one of the most-photographed locations in all of Antarctica, and there should be great photo opportunities. It sounded good to me, so I had set an alarm.

Our ship headed north and soon entered the Lemaire Channel, which is a strait between Kyiv Peninsula on Graham Land and Booth Island. Steep cliffs line the passage, often filled with icebergs – it it 6.8 miles long and only 2,000 feet wide at its narrowest point. The channel was first seen by the German expedition of 1873-74, but nobody traveled through it until December of 1898, when the ship the Belgica of the Belgian Antarctic Expedition passed through it. The leader of the expedition was Adrien de Gerlache, and he named the channel for Charles Lemaire (1863-1925), who was a Belgian explorer of the Congo. Icebergs often fill the channel, especially early in the season.

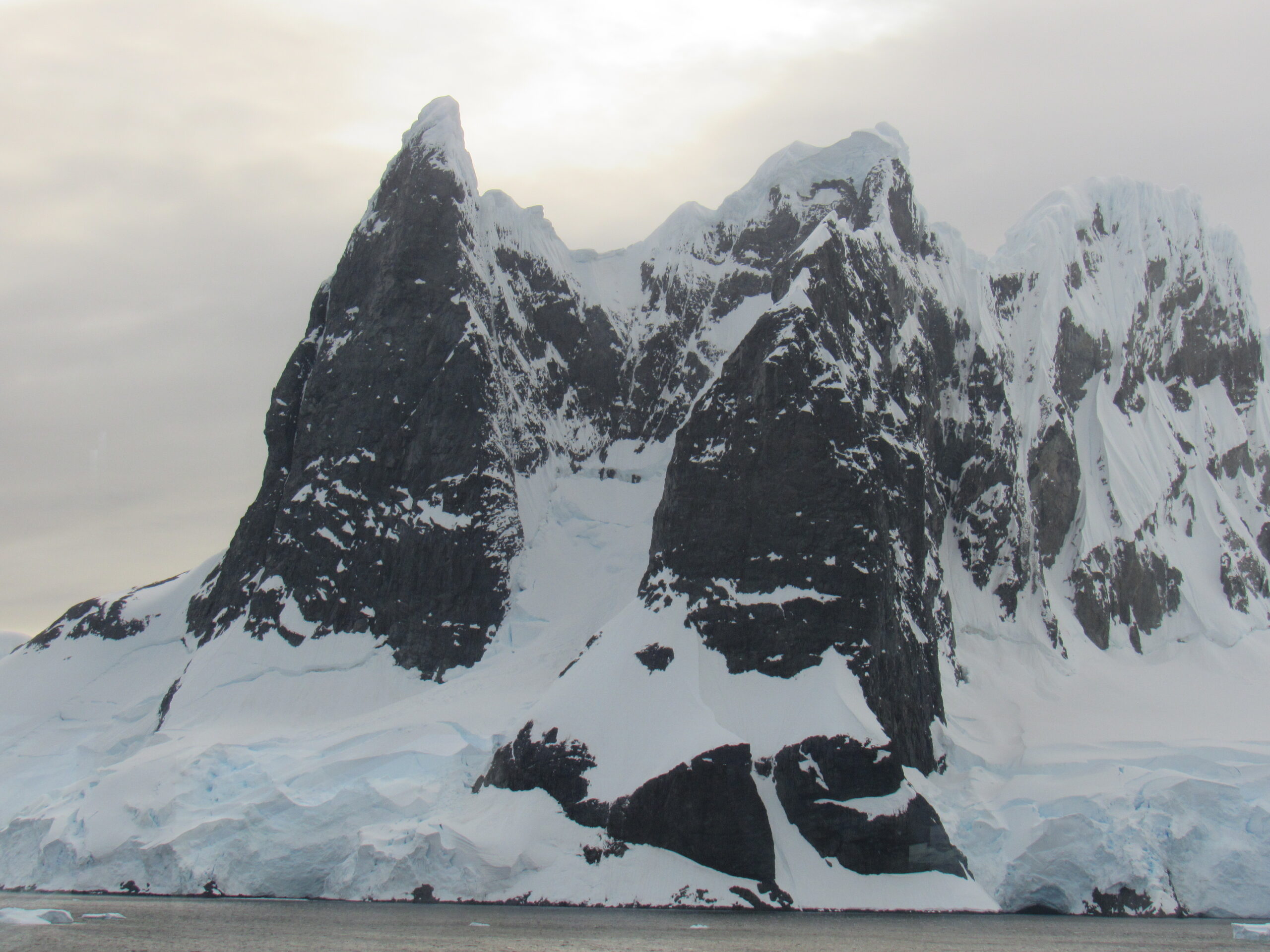

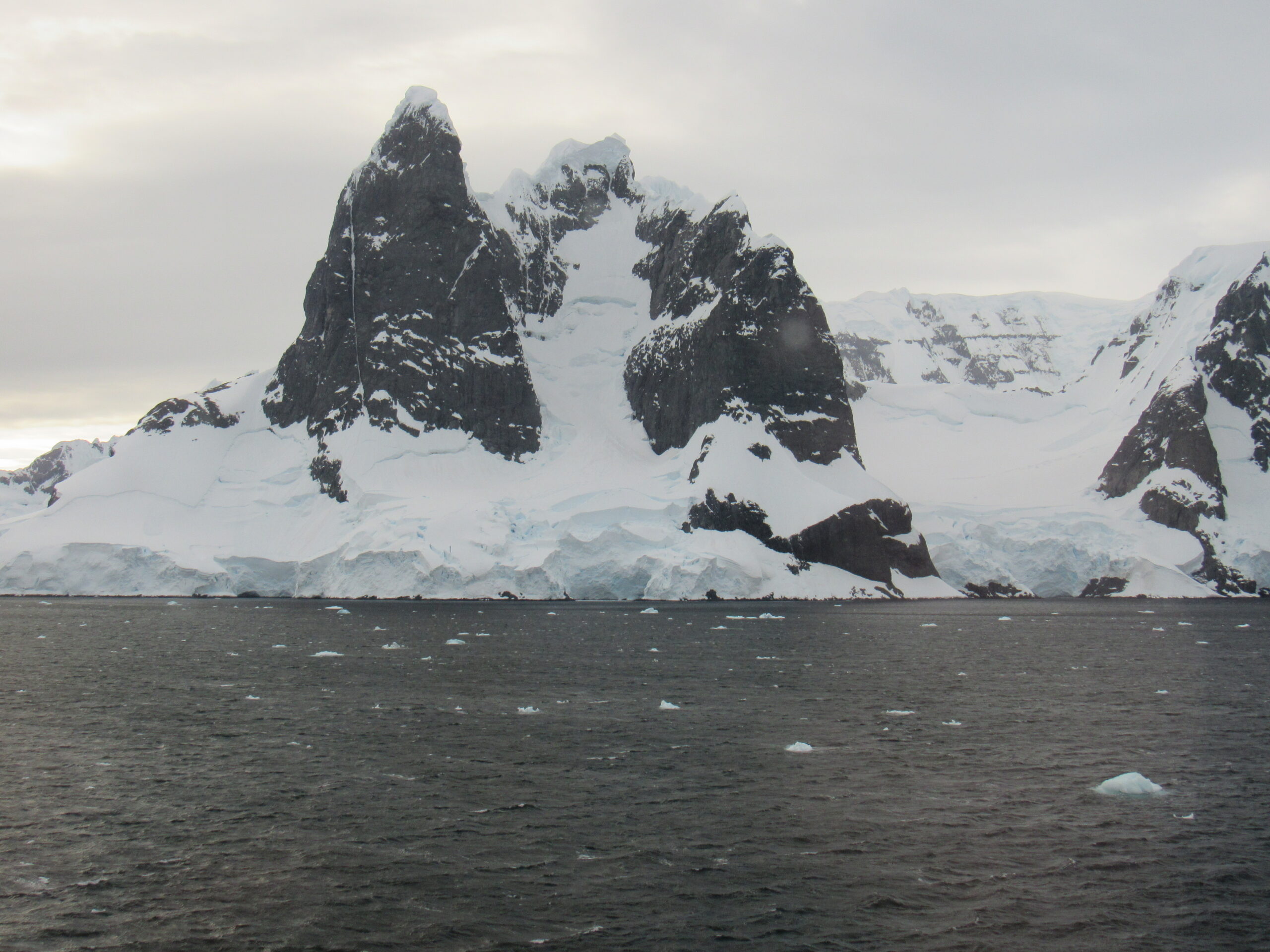

Booth Island is rugged, 5 miles long and rising to a height of 3,215 feet. The island was discovered and named by a German expedition, probably for Oskar Booth, a member of the Hamburg Geographical Society at that time. The island occupies most of the west side of the channel. These pictures were taken as we neared the island.

I took these next pictures from the observation deck of the ship as we passed the north side of the island. We are looking at the steep side of Mount Lacroix, whose high point is Cléry Peak, at 2,100 feet. It was named by Charcot after French mineralogist Alfred Lacroix.

Farther south on the island sits Wandel Peak, the highest point on the island at 3,215 feet. Way back in 1905, the explorer Charcot visited the island, and one of his geologists, Ernest Gourdon, climbed a peak with the guide Pierra Dayné. From Charcot’s writings, it seems that they may have climbed Wandel Peak. If that is true, then it is quite remarkable, as several teams have failed to summit in recent times, being stopped by difficult ground high up on the north ridge. In February of 2006, a very strong Spanish team led by José Carlos Tamayo almost reached the top, but had to stop only 50 feet short of the summit due to unstable snow mushrooms. In February of 2010, 3 French climbers from the ship Ada II climbed a couloir, reaching the summit ridge just north of the summit itself, then negotiated the sinuous crest and some wild cornices. They found that the top of Wandel Peak consisted of 2 summits separated by a short, narrow ridge. They visited both and found that the smaller and steeper second summit to the south was a few feet higher than the first.

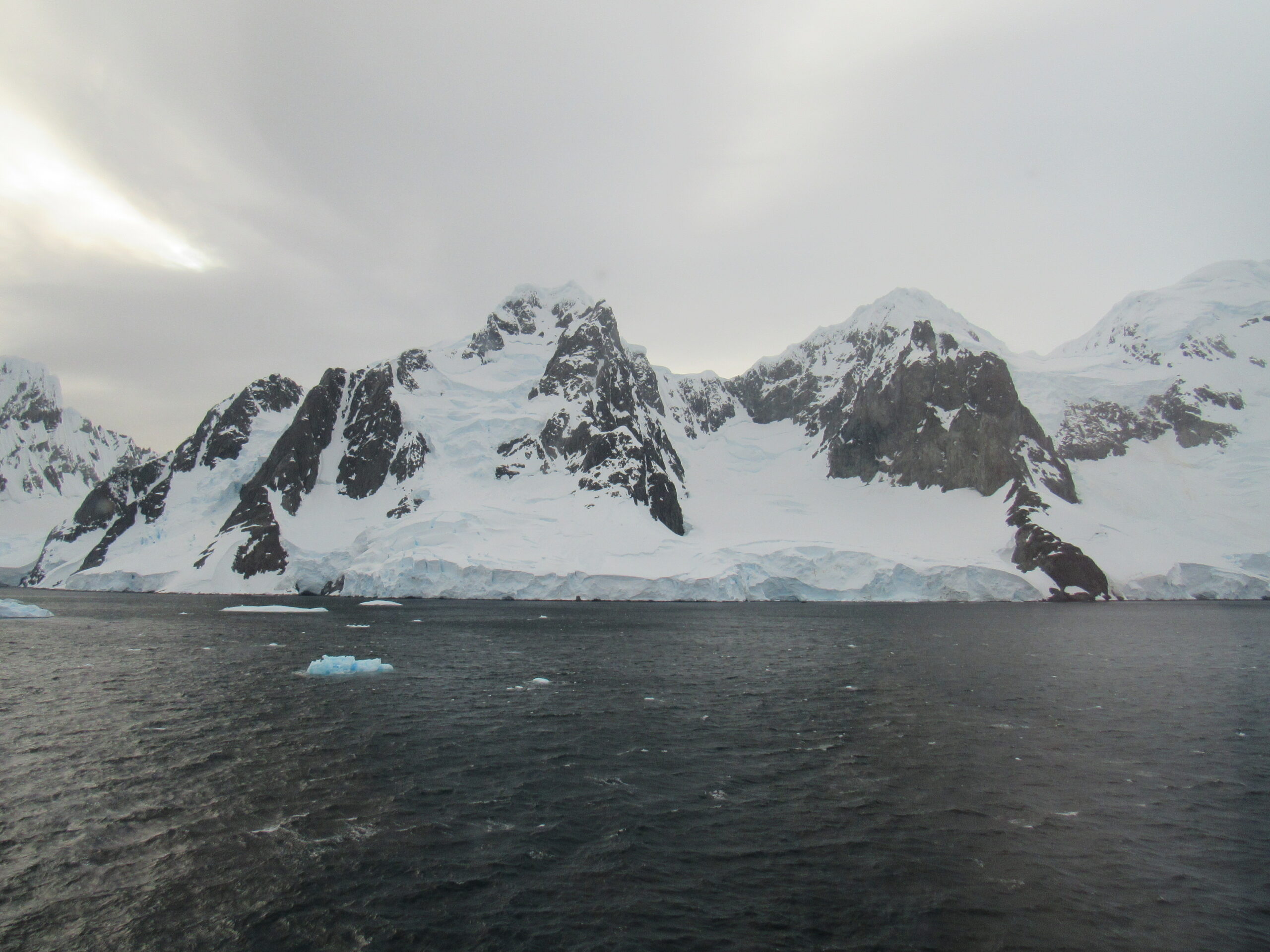

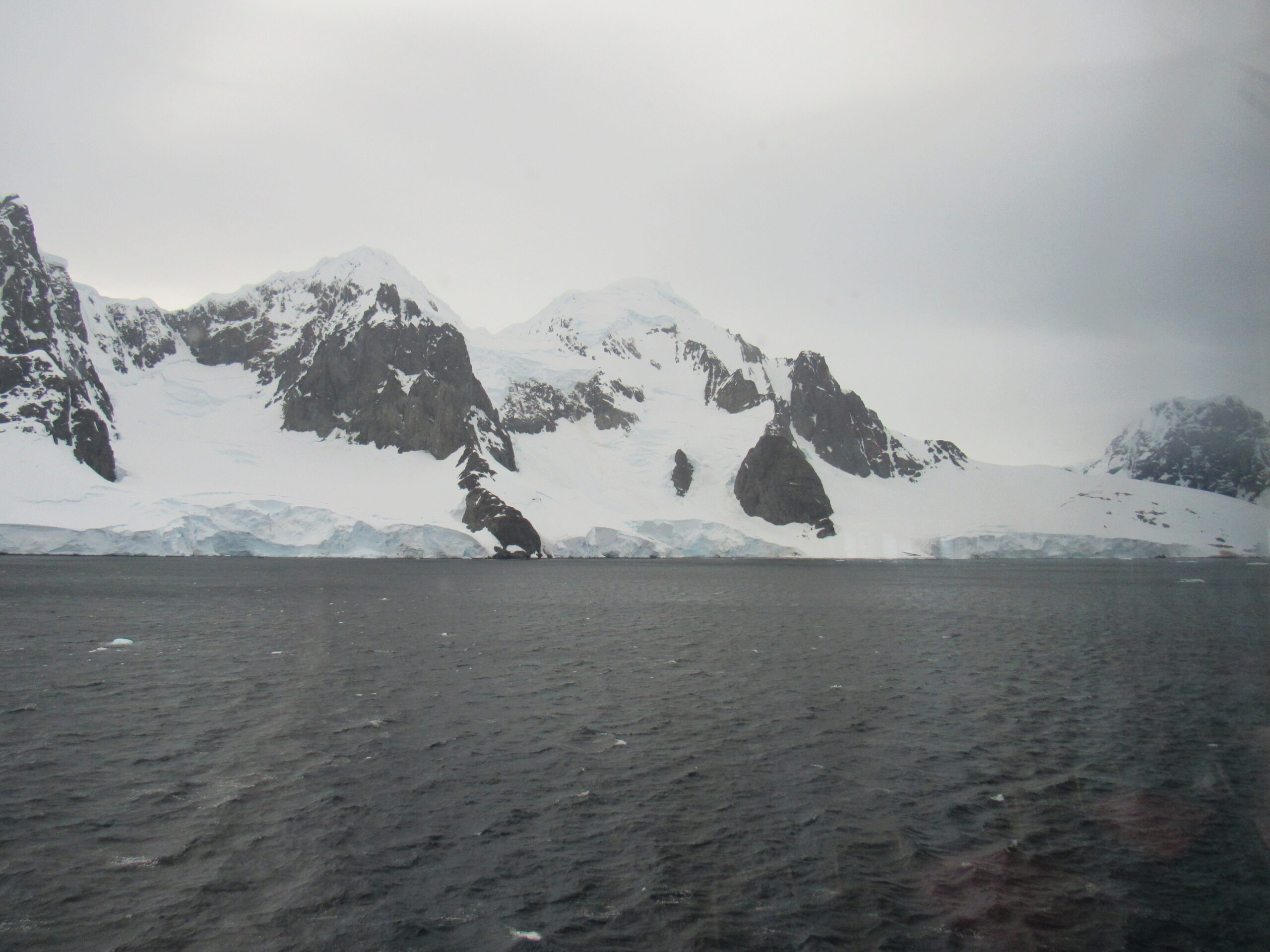

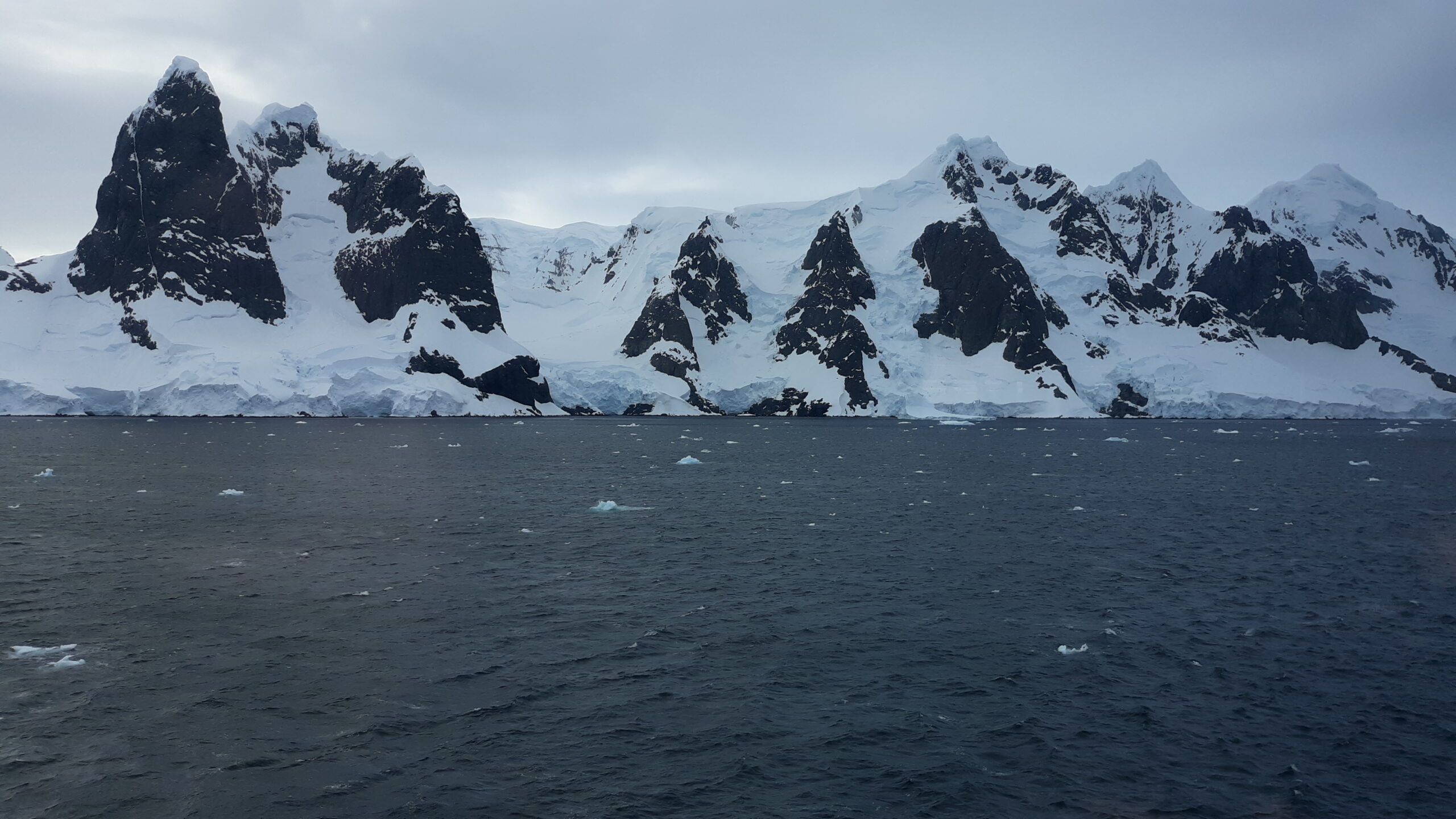

As we steamed north through the channel. the scenery changed quickly. The channel was only about 7 miles long, and as we were moving at almost 15 knots, we were all the way through in only half an hour. These next two photos show a part of the mainland, to the east of the channel.

The Humphries Heights (65°3′ S by 63°52’W) are a series of peaks extending southwest from False Cape Renard to Deloncle Bay, on the northwest coast of Kyiv Peninsula, Graham Land. They were charted by the Belgian Antarctic Expedition under Gerlache, 1897–99, and were named by the U.K. Antarctic Place-Names Committee in 1959 for Colonel G.J. Humphries, then Deputy Director, and future Director of Overseas Surveys. These were on our right side as we headed north through the channel, and are therefore on the mainland.

Here’s another view of Humphries Heights.

I don’t have any information about any climbs done in Humphries Heights, but just to the north of them is a group of peaks called False Cape Renard (65°2’S 63°50’W), which sits 1.5 nautical miles southwest of Cape Renard. It was charted by the Belgian Antarctic Expedition under Gerlache, 1897–99. This feature and Cape Renard together were called “The Needles” by Henryk Arctowski, geologist, oceanographer and meteorologist with the Belgian expedition. Since the two capes are easily confused and need to be distinguished, a collective name was considered unsuitable. The name “False Cape Renard” was applied by the French Antarctic Expedition, 1908-10, under Jean-Baptiste Charcot.

In December of 2007, the renowned Spanish rock climbers Eneko and Iker Pou, joined by a film crew, decided to attempt the westernmost summit of the 3 tops of False Cape Renard. They referred to it as Zerua Peak, which means Sky Peak. Bad weather trapped them for 4 days in camp, but the weather cleared unexpectedly during their Christmas Eve party. They stopped drinking and set off for a single push up the mixed northwest buttress. The lower easy section soon gave way to difficult rock climbing, often with a covering of verglas, all done in freezing conditions. They had only taken one set of ice tools, so the M6 mixed pitches took longer than normal and much of the rock was shattered, which made the F6b+ pitches climbed up high even more intense. They reached the summit, and they then spent 8 hours of rappelling to get back down to their friends in base camp 24 hours after they had started the climb. They named their route Azken Paradizua, and with 600 meters of F7a and M6, it is one of the hardest routes on the Antarctic Peninsula.

Just to the right of the line climbed by the Pou brothers is an unusually straight and narrow goulotte of ice that had caught the attention of passing climbers but nobody had touched it. That is, until the climbers on the ship Ada II arrived. Cortial, Daudet and Wagnon climbed 550 meters of ice up the line. They named it 42 Balais et Toujours pas Calmé. The remaining 2 virgin summits of False Cape Renard are also attractive.

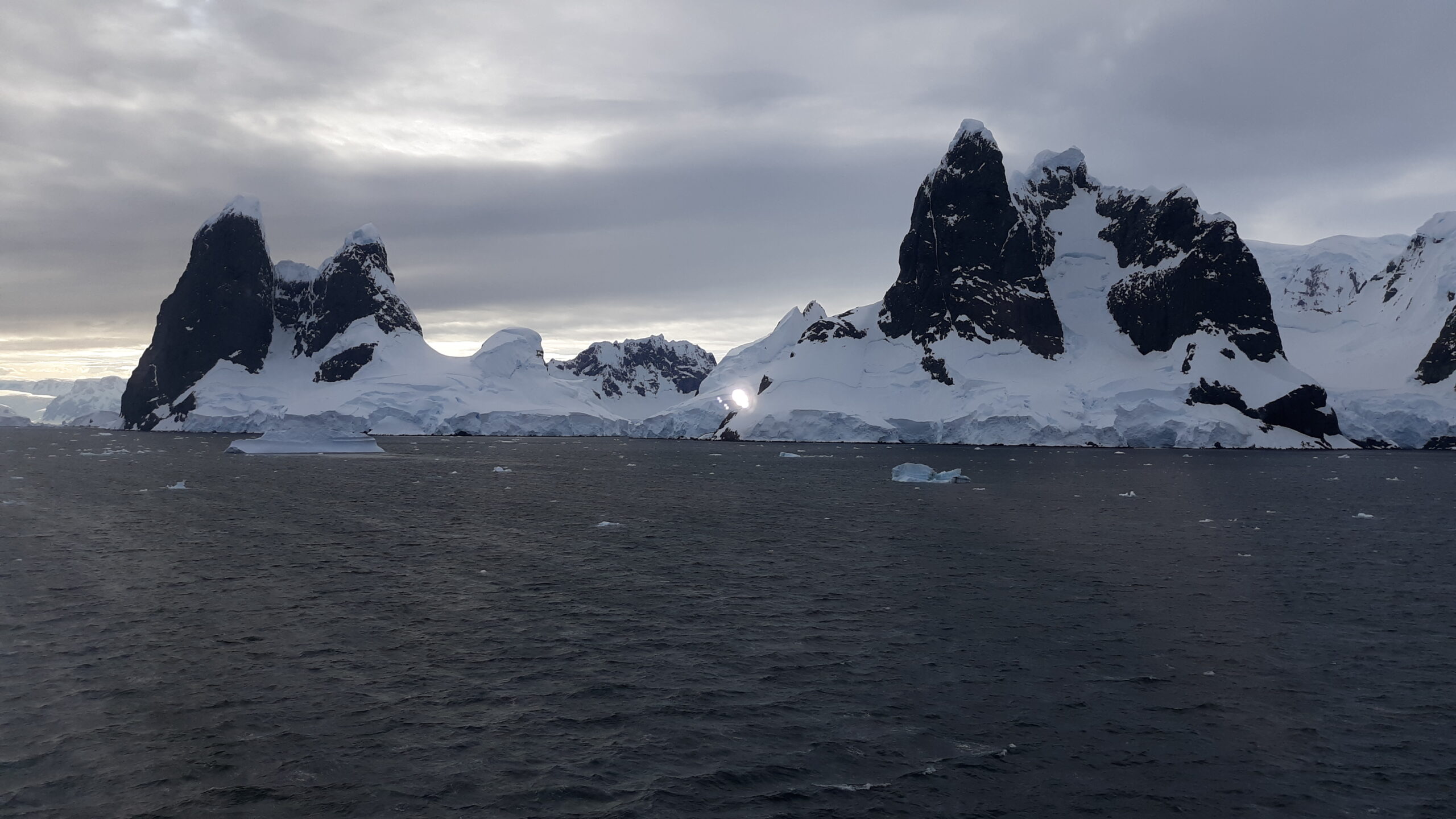

Here are some pictures I took of the summits of False Cape Renard.

Some of these pictures were taken with my camera, and some with my phone. This one shows False Cape Renard and the peaks to the south, which would be part of Humphries Heights.

The next peaks we came to, just north of False Cape Renard, were the peaks of Cape Renard. These sit on a little island all to themselves, appropriately named Renard Island. These are the most famous peaks along Lemaire Channel, and no doubt the most photographed. The most dramatic view is from the west side.

The tower on the left is the higher of the two, at 2,450 feet. Here is a close-up of the summit area.

The first known attempt to climb Cape Renard was back in February of 1996. Crag Jones and Julian Freeman-Atwood were no strangers to tough climbing in southern regions. The ship Pelagic dropped them at the base of the cape and they set up camp 25 meters above the ocean. Their first attempt on the central couloir of the north face provided 12 pitches of Scottish III terrain, but when they reached the base of the upper rock headwall, a stretch of bad weather forced them down. A few days later on another attempt, Jones pulled off a flake and took a minor fall, his injuries forcing them to descend once again.

A year later, Northanger set Canadians Jia Condon and Rich Prohaska down at the cape – they were fresh from climbing in the Wall Range on Wiencke Island. They fixed ropes up the first half of the east buttress, well left of the 1996 attempt. On February 4th, they arrived at the top of the buttress on a subsidiary top, but the cornice from there to the main summit was unstable and very dangerous, so they rappelled from that point.

The first ascent of Cape Renard finally happened in 1999. Renowned German climber Stefan Glowacz arrived with Kurt Albert, Hoger Hoeber, Hans Martin Götz, Gerhard Hiedorn and Jürgen Knappe aboard the yacht Santa Maria. They climbed the dark rock wall of the west face via a 17-pitch route 900 meters high, with free-climbing up to 5.12. They called the route Against The Wind, and it is almost certainly the most technically difficult route yet climbed on the Antarctic Peninsula.

This next photo shows the terrain just to the south of the peaks.

Here, we are looking back south along Lemaire Channel, the way we had come. You can see how narrow it is.

Here is a view taken a bit earlier, clearly showing Cape Renard on the left and False Cape Renard on the right.

Here is a view of the north face of the higher Cape Renard peak, where the climbing took place.

Our entire trip through Lemaire Channel only took half an hour, so as you can imagine, my shutter was clicking non-stop. Once we cleared the channel, we passed along the west side of Flanders Bay and then entered Gerlache Strait. Also known as Détroit de la Belgica, it separates the Palmer Archipelago from the Antarctic Peninsula. The Belgian Antarctic Expedition, under Lt. Adrien de Gerlache, explored the strait in early 1898 and named it for the expedition ship Belgica. However, the name was later changed to honor the commander himself. The strait led us northwest for a full 125 miles.

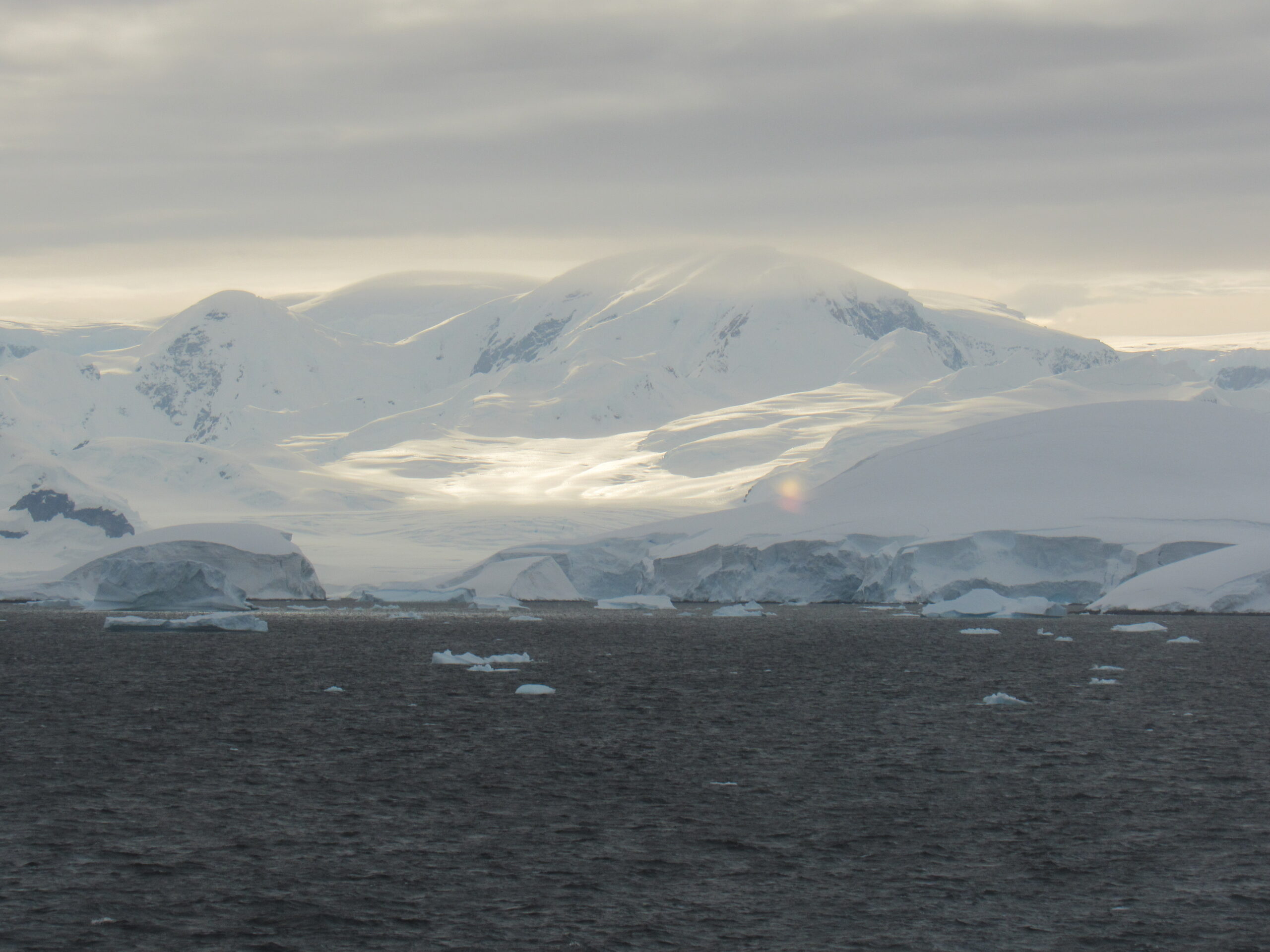

It was a solid overcast of a day as we motored along to the northeast through Gerlache Strait.

This video shows bits of ice floating in the ocean as we cruised along.

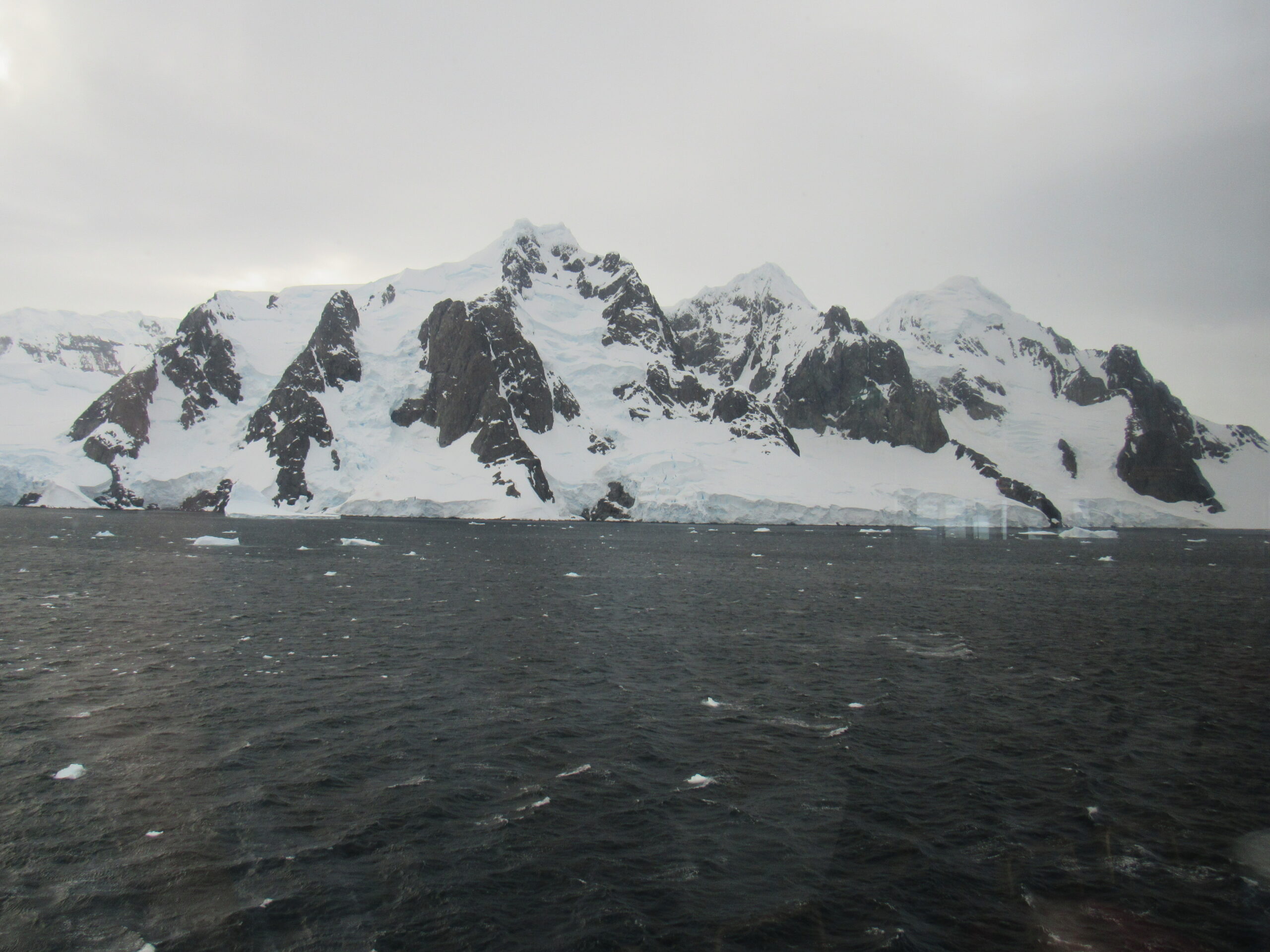

Tantalizing views of peaks on the mainland were all along the peninsula.

In spite of the overcast, we had good views along the Antarctic Peninsula.

Here is another video I shot, this one looking east to the mainland.

Since our day had started so early, we were all the way through Lemaire Channel by 7:30 in the morning. It had been announced that today we would make our way to a place called Orne Harbor, where a colony of chinstrap penguins would be found atop a ridge. As we sailed along, sometimes we would see a pod of Orcas, and even a humpback whale from time to time.

As the day progressed, the weather worsened. The captain announced that conditions at Orne Harbor were too rough for a landing. The clouds were almost down to the ocean, the wind was blowing up to 50 knots – there would be no shore parties, no kayaking, no nuthin’, and it was snowing hard. This was all decided in the early afternoon. Radio contact with other ships revealed that the weather was better in the Weddell Sea, so we would make our way there instead. This day, the 17th of January, had become a sea day, one where we would travel and not make landfall. Here are a few of the ship’s photos taken that day.

The science center on the ship afforded opportunities to learn about all manner of things from the scientists who were a part of the ship’s crew.

Every day, there were a few lectures given by experts among the science staff.

The crew who worked in the kitchen worked hard to provide delicious and well-presented meals. Did I mention that at lunch and dinner, you could have all the wine or beer your heart desired? – it was all included in the price of the cruise.

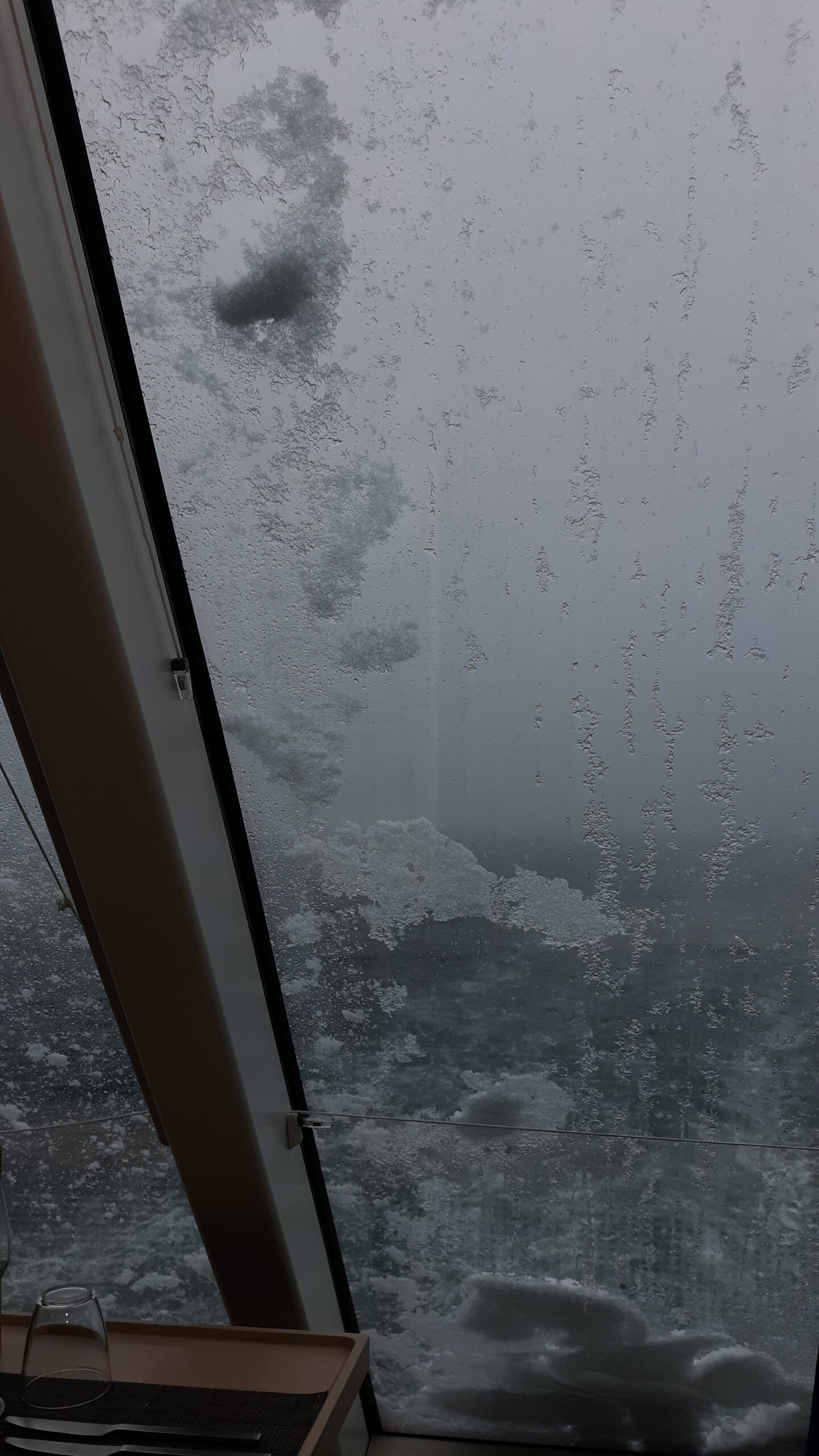

It was a relaxing day spent at sea. It did snow, however, all afternoon. The windows in the dining room showed it.

The captain said that tomorrow we would do a shore landing at a place called Tay Head. We were all looking forward to it.