Yesterday, our shore landing along the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula was canceled due to poor weather. Our captain, in radio contact with other ships, had learned that the weather in the Weddell Sea was better, so we made a beeline for it. To get there, we had to go all the way north to the very tip of the peninsula, then swing around to the east, then south, to enter the sea itself. Much of the southern part of the sea is covered by a permanent, massive ice shelf, the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf. The sea is named after the Scottish sailor James Weddell, who entered the sea in 1823. At its widest, the sea is around 2,000 kilometers (1,200 mi) across, and its area is around 2.8 million square kilometers (1.1 million square miles). This is bigger than the area of Argentina, and it would be the 8th-largest country in the world by area if it were in fact a country.

The Weddell Sea has been deemed by scientists to have the clearest water of any sea. Researchers from the Alfred Wegener Institute on finding a Secchi disc visible at a depth of 80 meters (260 ft) on13 October 1986, ascertained that the clarity corresponded to that of distilled water.

In his 1950 book The White Continent, historian Thomas R. Henry writes: “The Weddell Sea is, according to the testimony of all who have sailed through its berg-filled waters, the most treacherous and dismal region on Earth. He continues for an entire chapter, relating myths of the green-haired merman sighted in the sea’s icy waters, the inability of crews to navigate a path to the coast until 1949, and treacherous “flash freezes” that left ships, such as Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance, at the mercy of the ice floes.

In 1915, Endurance got trapped and was crushed by ice in this sea. After 15 months on the pack-ice, Shackleton and his men managed to reach Elephant Island and safely returned home. In March 2022, it was announced that the well-preserved wreck of the Endurance had been discovered four miles (6.4 km) from its anticipated location, at a depth of 3,008 meters (9,869 ft).

If you have never read the book Endurance – Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage, by the author Alfred Lansing (ISBN 0-7867-0621-X) do yourself a huge favor and get a copy, whether through your local library or buying one online. The Chicago Tribune had this to say about the book – “One of the most gripping, suspenseful, intense stories anyone will ever read”. That’s an understatement, Folks. I’ve read the book several times, loaned out my copy repeatedly, and still am awestruck by the story every time I read it. It’s hard to believe what they endured and how they survived. It will give you a impression of the Weddell Sea that you’ll not soon forget, and also of the resilience of the human spirit.

Our goal today, Thursday, January 18th of 2024, was an obscure spot called Tay head. In order to reach it, we had ploughed our way through poor weather all day yesterday, along the west side of the Antarctic Peninsula, then all through the night. Very early in the morning, we had swung around to the south, through a passage called Antarctic Sound. The northernmost end of the Antarctic Peninsula, which is part of the mainland of the continent itself, is a place called Trinity Peninsula. Joinville Island sits to the east of the peninsula, and Antarctic Sound separates them. The sound is also referred to as “Iceberg Alley”, because of the huge icebergs that are often seen here.

These maps will show some of the details.

Joinville Island (63°15’S 55°45’W) is the largest island of the Joinville Island group, about 46 miles long in an east–west direction and 14 miles wide, Tay Head sits on the south side of the island.

Joinville Island was discovered and charted roughly during 1838 by a French expedition commanded by Captain Jules Dumont d’Urville, who named it for François d’Orléans. Prince of Joinville (1818–1900),

The Firth of Tay (63°21’S 55°34’W) itself is a rocky headland 6.9 miles east of Mount Alexander, extending into the Firth of Tay on the south coast of Joinville Island. The name is derived from the Firth of Tay on the east coast of Scotland. Very few visitors try to land here. The firth is 2 miles long and 6 miles wide, extending in a NW-SE direction between the NE side of Dundee Island and the E portion of Joinville Island. It merges to the NW with Active Sound with which it completes the separation between the islands. It was discovered in 1892-93 by Capt. Thomas Robertson of the Dundee whaling expedition.

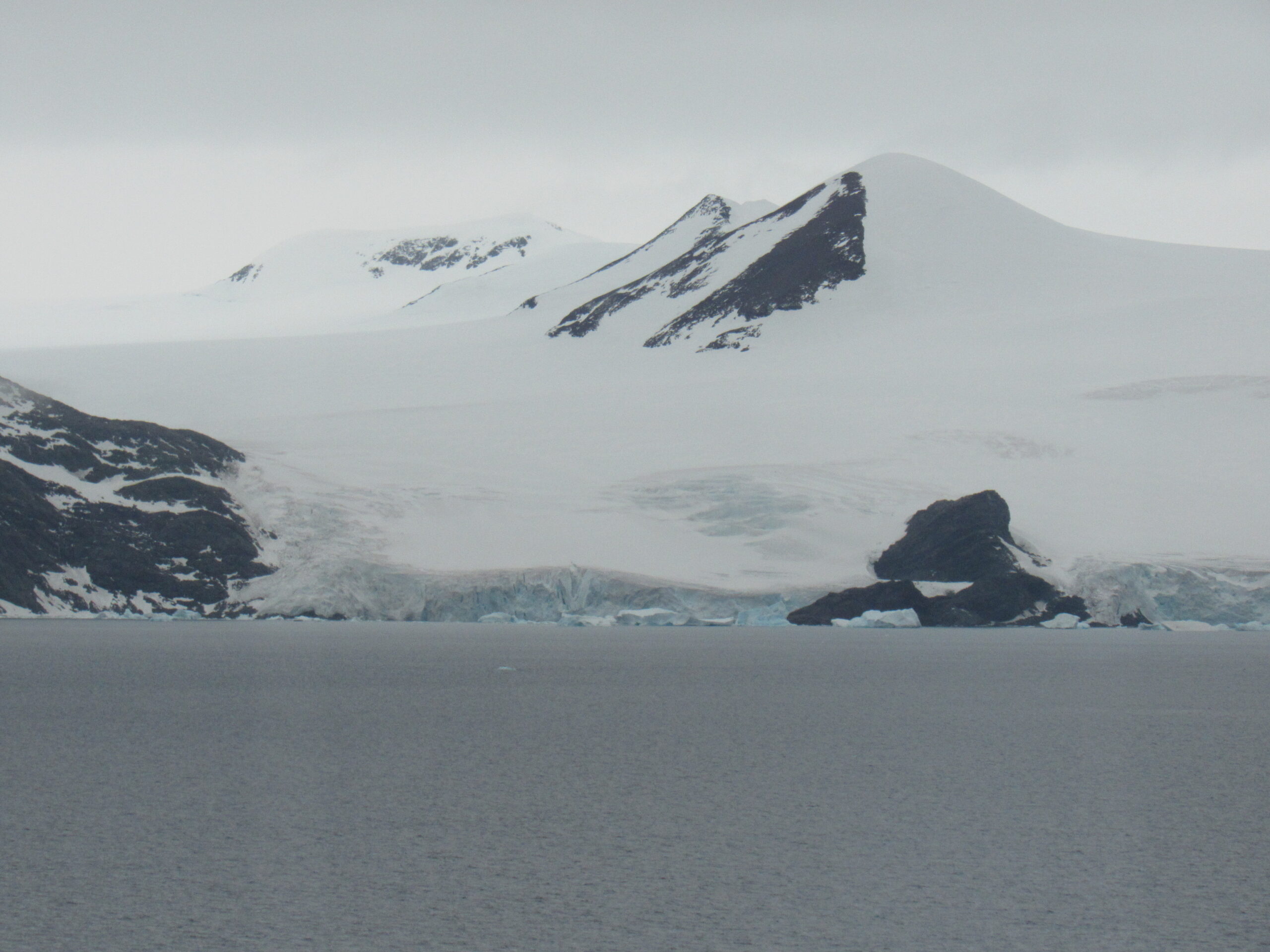

Okay, so much for history and geography for the time being. Let’s have some pictures. By about 10:15 in the morning, we approached the area on a grey, overcast day.

We were now all the way back to 63 degrees north latitude, having moved much farther away from the pole, yet even in this relatively balmy climate, large ice sheets covered much of the land out on these islands.

Perhaps the penguins were staying on the floating ice to avoid predators like orcas and leopard seals.

Here is a video I took of the penguins swimming quickly through the water. They are slow and awkward on land, but quick and graceful in the water.

By the time our ship had found a good spot and stopped, it was almost 2:00 PM. We had already enjoyed a lunch, and the zodiacs started taking us ashore. We had reached Joinville Island, gone around its southwest end, and into a channel between it and Dundee Island.

Here we were, making our landings at the beach at Tay Head. The expedition team in their yellow jackets took great care of us. A firm arm’s grasp guided each of us out of the zodiac and safely on to the land.

Our ship, the Roald Amundsen, offshore. The zodiacs traveled quickly back and forth from ship to shore.

Here is video of the Adélie penguins up close.

There was a strict rule of keeping a minimum distance of 15 feet between us and any wildlife. Sometimes penguins came closer than that, and if they did, we had to stop in our tracks and wait for them to travel past, no matter how long it took.

The colonies we visited had anywhere from hundreds to thousand of birds. As you can tell from the video, they could be quite noisy places. What you can’t tell from the video is that they were smelly places. All of the penguin poop really added up. Some of the birds looked quite dirty, but as soon as they went swimming, they were clean again.

Here are more views of the colony.

Here’s a higher look to the upper part of the colony.

Skuas would often nest among the penguins. They were opportunistic, and would eat penguin eggs and even chicks if they could catch them when they were small.

These skuas weigh up to 3.5 pounds and have a wingspan of 48 inches.

Here is a panoramic video I shot, showing much of the land around Taye Head.

Here’s another view of penguins and ice.

The Adélie penguin chicks were now several weeks old and getting big quickly. They were fed by the parents who regurgitated food for them to eat. This video shows that.

Penguins would propel themselves along the snow or ice by pushing with their hind feet, which had sharp claws. Quite efficient, really.

This landing at Tay Head was easier than some of the others. A step off the zodiac into 10 inches of ice-cold sea water, then a climb up a short bank of small, loose rocks. From there it was a walk of about a quarter of a mile on flat ground to arrive at the main penguin colony. Something I haven’t shown you were the remains of penguins on the shore. There were skeletons scattered around, and they had been picked clean by scavengers. There were no ants or beetles here to do that job, as you would find in warmer climates. A certain percentage of the chicks don’t make it to the stage where they can enter the water and swim and start to look for food on their own, but I’m sure that is a small number. Here are some nice photos taken by the ship’s photographer.

An Adelie penguin on the left and a lone Chinstrap penguin on the right. We would head to a colony of Chinstraps in the coming days.

We saw southern giant petrels from time to time. They are opportunistic feeders and are extremely aggressive and will kill other seabirds, as well as being scavengers. At sea, they feed on squid, krill and fish. These are big birds, weighing up to 17 pounds (twice the weight of a male bald eagle) and having a wingspan of up to 83 inches (that’s as big as a bald eagle).

The snowy sheathbill is a bird we saw from time to time. As I learned more about it, I decided that this guy is a disgusting little creature. It is the only land bird that is native to the Antarctic continent. It is an omnivore, a scavenger, and a kleptoparasite and will eat nearly anything. It steals regurgitated krill and fish from penguins when feeding their chicks and will eat their eggs and chicks if given the opportunity. Sheathbills also eat carrion, animal feces, and, where available, human waste. It has been known to eat tapeworms that have been living in a chinstrap penguin’s intestine. I suppose that, given its ability to survive where most would fail, this behavior could be forgiven.

We were in an area where Emperor penguins lived and raised their chicks, but it was late enough in the summer that they had all now left: their chicks have fledged and the colonies have dispersed. Too bad, it would have been exciting to see a bunch of them.

The plan for tomorrow was to head north to the South Shetland Islands, the outer band of islands to the north of the Antarctic peninsula.

Please stay tuned for Chapter 10 of this journey.

numerous Weddell seals rest. Giant petrels feed on dead Fur seals that have been trapped in the frozen snow since last season and now, with the summer thawing, represent a good source of nourishment.