Porcupines

These are curious creatures. Because of their sharp quills which easily penetrate skin and flesh, most animals give them a wide berth. They are found on 5 continents and include a large number of species, with a total of 17 different ones in the New World alone. I have only seen one type, and that is the North American porcupine, Erethizon dorsatum. All of my encounters have been in Canada.

One winter, back in the 1970s, I saw one in a tree eating bark. That was near Robson Pass in the Canadian Rockies. Another occasion was when I spent the night in a log cabin near Yoho Pass in 1966, where a porcupine gnawed on the wood under the floor all night long, making it impossible to sleep. However, my favorite encounter was on Canada Day in 1988. We were returning from an unsuccessful attempt on the northwest arête of Mt. Sir Donald, and as we entered the forest on our descent, I spied a porcupine and her baby. The little one was very cute, and I learned that a baby is called a porcupette.

Thick Blood

When you climb to a really high altitude, one of the physiological adjustments that the body makes is an increase in red blood cells in response to low oxygen. The blood thickens so much that scientific expeditions report difficulties in drawing samples. The blood clots like jelly either in the needle or in the syringe before it can be transferred to a vial. The combination of thickened blood, inactivity enforced by bad weather and dehydration caused by the excessively dry atmosphere makes blood clots a common occurrence in climbers who go to high altitude.

Dead Baby

Back in the 1980s, I climbed a peak in Mexico, just a few miles south of the border. On my way back down from the summit , when I was most of the way down, I had an experience which I still remember vividly all these years later. Out in the open on the steep rocky mountainside, I came upon a dead bighorn sheep – it was just a baby, and had died only recently. Seeing it had a powerful effect on me, and I was overcome with emotion. What a harsh and unforgiving land this desert was – such a struggle to stay alive. One mis-step and you’re gone. Through my tears, I wondered how it had died – I doubt it had weighed but 15 pounds. I lingered a while, then left, the sobering memory staying with me on the scorching 103-degree walk back to the border.

Memory Lapse

I had spent almost a month on the mountain, and 5 nights at an elevation the same height as the summit of Canada’s Mount Logan. My guess is that I fried a few brain cells during that time up high, and here’s why I say that. Shortly after coming back down off of the mountain, I was back in the city and really enjoying my time there. Several days passed, and one evening, I went to the office of the telephone company. There, the operator placed a long-distance call for me to my wife back in the USA. When she answered and realized it was me on the other end of the line, she burst into tears. She then proceeded to tell me that that evening was the absolutely latest date by which I was to call her and let her know I was safely down off the mountain. If I hadn’t called by that evening’s deadline, she was to contact the American embassy and report me missing. That news was a complete shock to me, and I told her I had no recollection of ever having agreed to such a deadline with her. She was incredulous – how could I possibly forget something so important? I could only attribute my memory lapse to having spent so much time up high and destroying a bunch of brain cells.

Fording

What does it mean to ford a river? Usually, it means to cross at a shallow spot, either on foot or in a vehicle. It can be tricky, and even dangerous. The first time I ever had to do it was when in the Wind River Range in Wyoming. Brian Rundle and I had just come down from climbing a couple of 12,000-footers and were making our way back to camp. In the Titcomb Basin, we came to a river that sat squarely in our way – we had no choice, it had to be crossed. The water didn’t look too swift, but we weren’t sure how deep it was. Not sure of what kind of footing we’d encounter, we decided to keep our heavy leather mountaineering boots on for the crossing. It went okay, and as I recall it wasn’t above mid-thigh deep, but it was icy cold. Our ice axes gave us extra stability, and we were soon safely across, and glad we wore our boots for the uneven bottom. The only downside of keeping our boots on was that they never did dry out properly during our remaining few days of climbing, which really sucked.

The only other memorable time I had to ford a river was in Argentina 4 years later, in December of 1990. The trail came up to the edge of the Río Horcones and continued on the other side. I knew I’d have to cross there, and to prepare I’d bought a pair of throw-away rubber sandals while I was still in the city. They worked perfectly to cross the ice-cold, glacier-fed water, thus keeping my boots dry. Unlike the previous ford in the Wind Rivers, which was across clear smooth water, this one was turbulent muddy water with plenty of whitecaps. It was almost crotch-deep and plenty concerning, but I made it across okay.

These crossings can be dangerous. A friend died while fording a river in the Brooks Range of Alaska several years ago. He was wearing a full pack, and was swept off his feet and drowned.

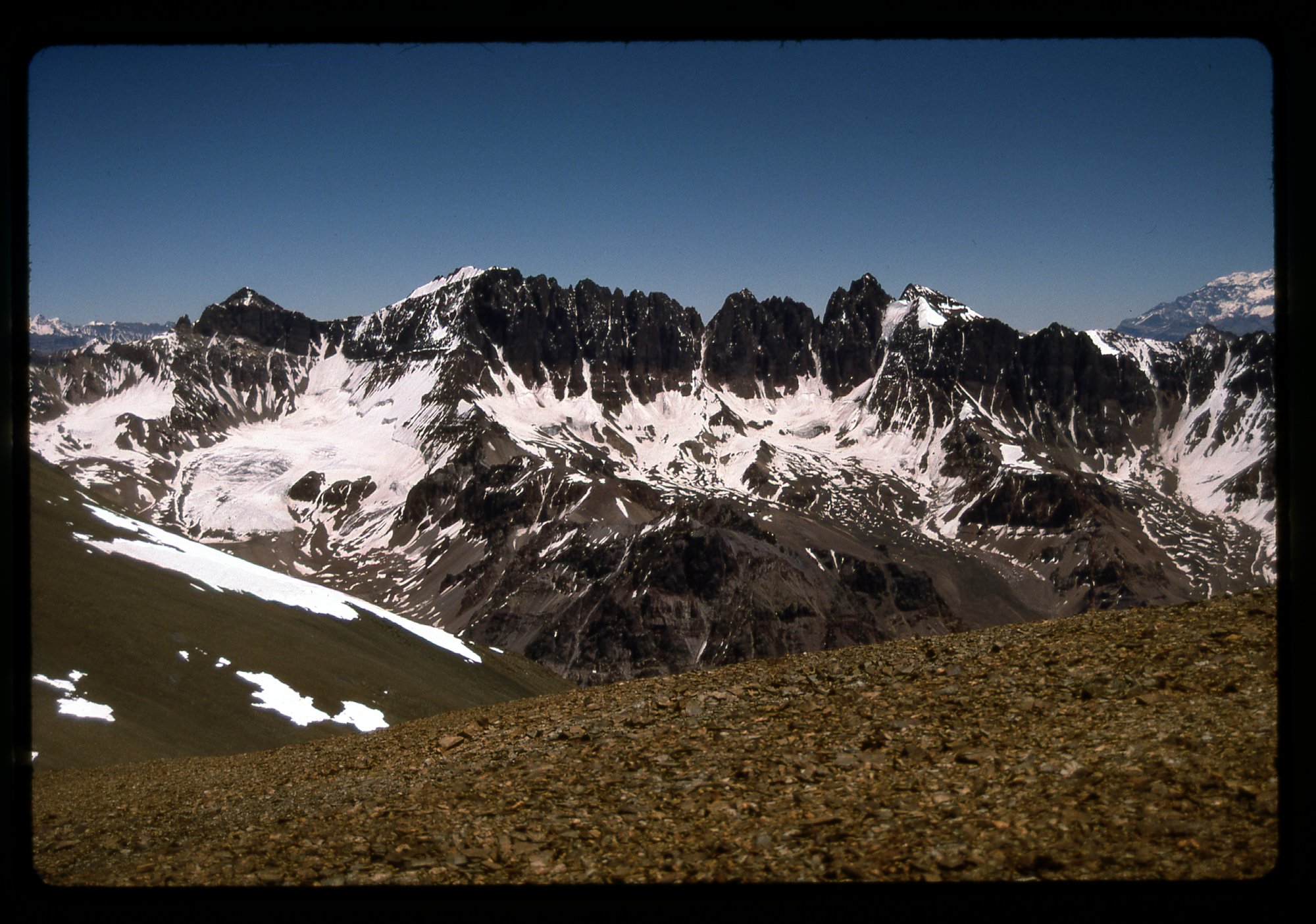

Quebrada de la Jaula

Have a look at this photo. The place I was standing was at an elevation of around 18,000 feet. I am looking west across a valley called La Quebrada de la Jaula, which roughly translates as Cage Valley. Those jagged peaks appear to be at least as high as I was, and I don’t believe that any of them have names. Beautiful, huh?

High Sunset

One evening, I was camped at a spot called Plaza Canada at an elevation of 16,000 feet. This was on the west side of Cerro Aconcagua. It was a scenic spot, to put it mildly. This photo has us looking up towards the summit area, which was still a full 7,000 vertical feet above me – it made me tired just thinking about it, all of the effort still to come.

Goofy Descent

Many years ago, climber friend Andy and I decided to head south of the border and climb a prominent Mexican peak called Cerro Cubabi. It was mid-March, and the day felt pretty warm. We had to slog up an old road, then begin the climb itself up through a lot of brush and cliffs. Hours later, we stood on the summit, tired and dehydrated, and feeling quite done-in by the ascent. After a short stay on top, we made plans to head back down. Andy was in favor of returning by the same route we had ascended, which was at least a known quantity. I suggested we drop straight down from the summit to reach that road in the valley bottom, cutting off a mile or two of the return trip. Andy reluctantly agreed to my idea, but said he’d hold me personally responsible for any shitty surprises we might run into on that unknown route.

Down we went, and before too long we encountered bands of cliffs we had to negotiate. It was all we could do to keep descending and not get cliffed-out. Here’s a view of what turned out to be pretty typical terrain we dealt with.

We had to drop a full 2,700 vertical feet, much of it through nasty and challenging ground like you see in the picture. There was a lot of tricky route-finding to be done. We had little to nothing left to drink, and were getting punchier in the heat as time passed. At some point, we started to joke around, saying how much we looked forward to getting back to the truck with its cooler full of cold drinks. All we had to do was to get back down through the cliffs to the road in the valley bottom and our troubles would be over. We would have reached the Land o’ Goshen, the Land of Milk and Honey, the Promised Land. Coming up with names like that and laughing our way through the misery kept us going. What awaited was the Land of Plenty, Shangri-La, Seventh Heaven, Paradise, the Garden of Eden, Nirvana, Xanadu. Well, we finally made it all the way down to the road. Hindsight showed, however, that we should have taken Andy’s route back down in the first place, to have avoided all of that misery.

Altimeter

Back in the days long before GPS, a climber considered herself pretty lucky if she owned an altimeter. The reading the device gave you was a result of how barometric pressure changed with elevation. However, unless you came to places with a known elevation where you could reset the altimeter to the correct reading from time to time, you could end up with an error of up to a couple of hundred feet by the end of the day if the weather was changing. That was the downside.

However, because the reading changed along with the weather, you could actually use it as a weather forecasting device. For example, if you were camped at one spot for some time, by keeping an eye on how the elevation reading changed, you could get a pretty fair idea if the weather was improving or getting worse. This happened to us in 1977 on a trip into the Lillooet Range. We were trapped on an icefield in a multi-day storm waiting for the weather to improve so we could move on. During the second night, the altimeter showed a lower and lower elevation reading, so we knew the barometric pressure was rising and that meant that fairer weather was coming. Lo and behold, when morning came, blue skies arrived and we could move on with our climbing.

Gift of Food

Things seemed about as grim as they could be. I was stuck at a spot known as Berlin Camp on Cerro Aconcagua in Argentina. Every day storms would dump more snow, pinning me down at an elevation of 19,525 feet. That’s as high as the summit of Mount Logan, the highest peak in Canada. It had snowed every day for the past week. Some climbers tried to reach the summit but had been forced back by deep snow. One group led by Mountain Travel said they had a temperature reading of minus 30 degrees where they turned back. As they were packing up to head back down the mountain, they very generously gave me a lot of food, and fuel for my stove. Their climb was over, so they didn’t need it any more. It was enough to keep me going for 7 days more.

Some of the Mountain Travel group. On the left is Ricardo Torres, the first person from Latin America to climb Mt. Everest; in the middle is Augusto Torres from Huaraz, Peru; on the right is Sergio Fitch, their climb leader.

Lucky Dog

Have a look at this dog.

She may look like your average dog, but she’s anything but. Her name is Makalu – that happens to also be the name of the 5th-highest mountain in the world. When I met her, she was about 4 months old. That took place on Cerro Aconcagua in Argentina. She lived at the Plaza de Mulas base camp at 14,000 feet. She would accompany climbers up the mountain, and to the summit at almost 23,000 feet. Apparently she had done that numerous times. Her mother had also done that several times, so she came by it honestly. She was supremely well-adapted to the altitude, and loved nothing more than to accompany climbers. She was treated with love and respect. I imagine that once the summer climbing season ended, she would live with climbers back in the city. Lucky dog!