Be sure to read the previous two chapters of The Bucket List before starting this one.

The date was Friday, January 12th, the fifth day of our trip. Yesterday had been exciting – the amazing scenery in Crystal Sound, then stopping at the sea ice in the evening. And, of course, the fact that the entire day was spent below the Antarctic Circle. Once we left the frozen sea ice, we headed west and, during the night, had traveled all the way down the west side of Adelaide Island.

The island is the largest one on the west side of the Antarctic Peninsula which can be circumnavigated. It is 86 miles long by 23 miles wide, with an area of 1,800 square miles, making it 50% bigger than the state of Rhode Island. The British research station called Rothera sits on its southeastern shore. The island was first discovered in 1832 by the British, but not surveyed until 1908 by the French.

Morning found us at the southern end of Adelaide Island, and we then headed east toward the Antarctic Peninsula. By noon, we were stopped at 67 degrees 48 minutes south by 67 degrees 16 minutes west. It had been overcast all morning, and the temperature was 35 degrees F. We spent much of the afternoon at a place called Horseshoe Island.

Located in Bourgeois Fjord, Marguerite Bay along the west coast of Graham Land, Antarctica, the small rocky island of Horseshoe was discovered and named by the British Graham Land Expedition under John Rymill who mapped the area by land and from the air between 1934 and 1937. It was named because of the U-shape of its mountains which climb as high as 900m (2,952ft). The island is about 8 miles long by 4 miles wide.

The base on Horseshoe Island was established by the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (the precursor to the British Antarctic Survey) in 1955. The site, along with several other bases opened during this period, was part of the push to increase UK scientific activity ahead of the International Geophysical Year (IGY), a worldwide program of geophysical research that was conducted from July 1957 to December 1958, which paved the way for the Antarctic Treaty in 1959.

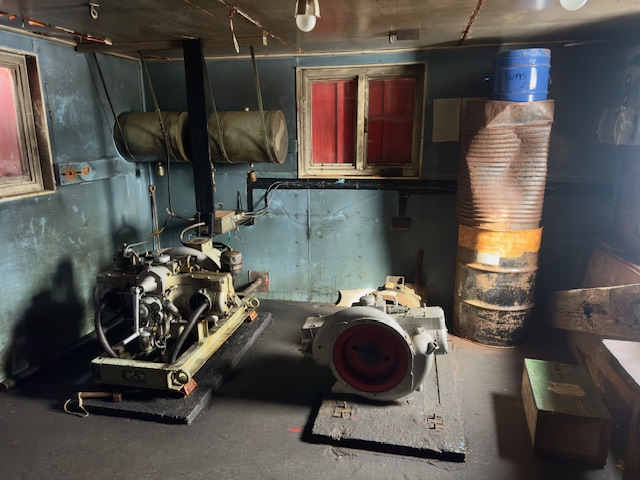

Horseshoe Island Hut provides a fascinating time capsule of the life and science of the time and remains relatively unaltered from its times as a British scientific base in the 1950s. The site features a balloon shed, pup pens, an emergency store, two pram dinghies and a winch. Artefacts have been catalogued and stabilized to an extent. Blaiklock, a refuge hut located several miles away, is considered an integral part of the base.

At this point, I need to tell you something about how travel to Antarctica is regulated. There is a group called the IAATO, which is the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators. Its members all agree to a set of strict guidelines which govern how their passengers will behave when visiting the continent. When it comes to visiting any spot on land, certain rules must be followed. The ship must contact the IAATO ahead of time by satellite telephone and obtain permission for a landing. If a ship carries more than 500 passengers, nobody is allowed to go ashore. There can be only one ship at a time visiting a site, with a maximum of 2 ships per day (midnight to midnight) of which no more than 1 can carry over 200 passengers.

The UK stipulates that the maximum number of visitors at any time, exclusive of expedition guides and leaders, is 100, and no more than 12 visitors are allowed inside the hut at any one time. These guidelines must also be followed:

- A record of each visit should be left in the Visitors Book, located in the base.

- All boots and outdoor clothing should be cleaned of snow and grit before entering the building. All backpacks and large bags should be left outside the hut.

- Any significant damage to the roof should be reported to the British Antarctic Survey.

- Artefacts should not be handled or removed from the site. Do not sit on chairs or other furniture, or lay objects down on tables or work surfaces.

- Expedition Leaders should provide the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust with a report on the condition of the Base.

- Loose gravel, mud and snow should be swept up, and floors wiped dry after each visit.

- No overnight stays in the hut are allowed. The hut is available for educational visits and, except in emergency circumstances, should not be used for any other purpose.

- Smoking and the use of candles, matches or stoves are prohibited in and around the hut.

- The hut windows are all covered with fixed shutters and so electric torches will be needed to see anything of the interior.

- Visitors are to leave the base safe and fully closed up on departure.

The ship stopped a few hundred yards offshore and groups were taken in the zodiacs to land near the buildings. I think you’ll like these photos of the base and its surroundings.

A peak rising up behind the base. This one is 1,762′ elevation, but the highest peak on the island rises to 2,952 feet.

These next pictures were taken inside the hut and are used here with kind permission of my friend Lisa. They give a good idea of what life was like for the crew who lived here.

Nurses from the medical clinic visited me to see how I was doing, and they were surprised to see that I had no symptoms whatsoever from the Covid. They also brought me a certificate prepared by the ship to show the exact date and time and location where I had crossed the Antarctic Circle (all passengers got one). We stayed near Horseshoe Island until mid-afternoon. This was near the base.

These small icebergs were near the base.

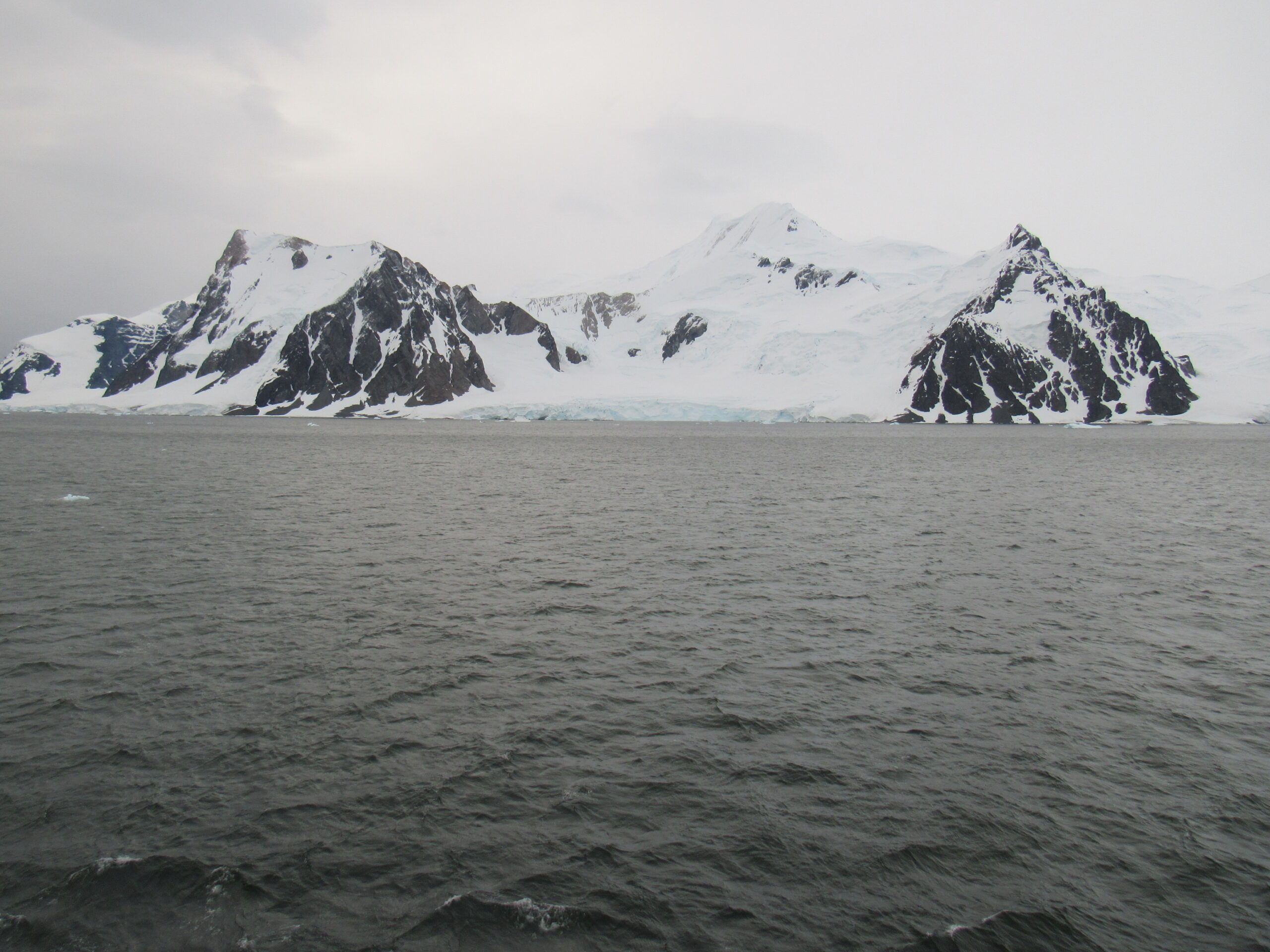

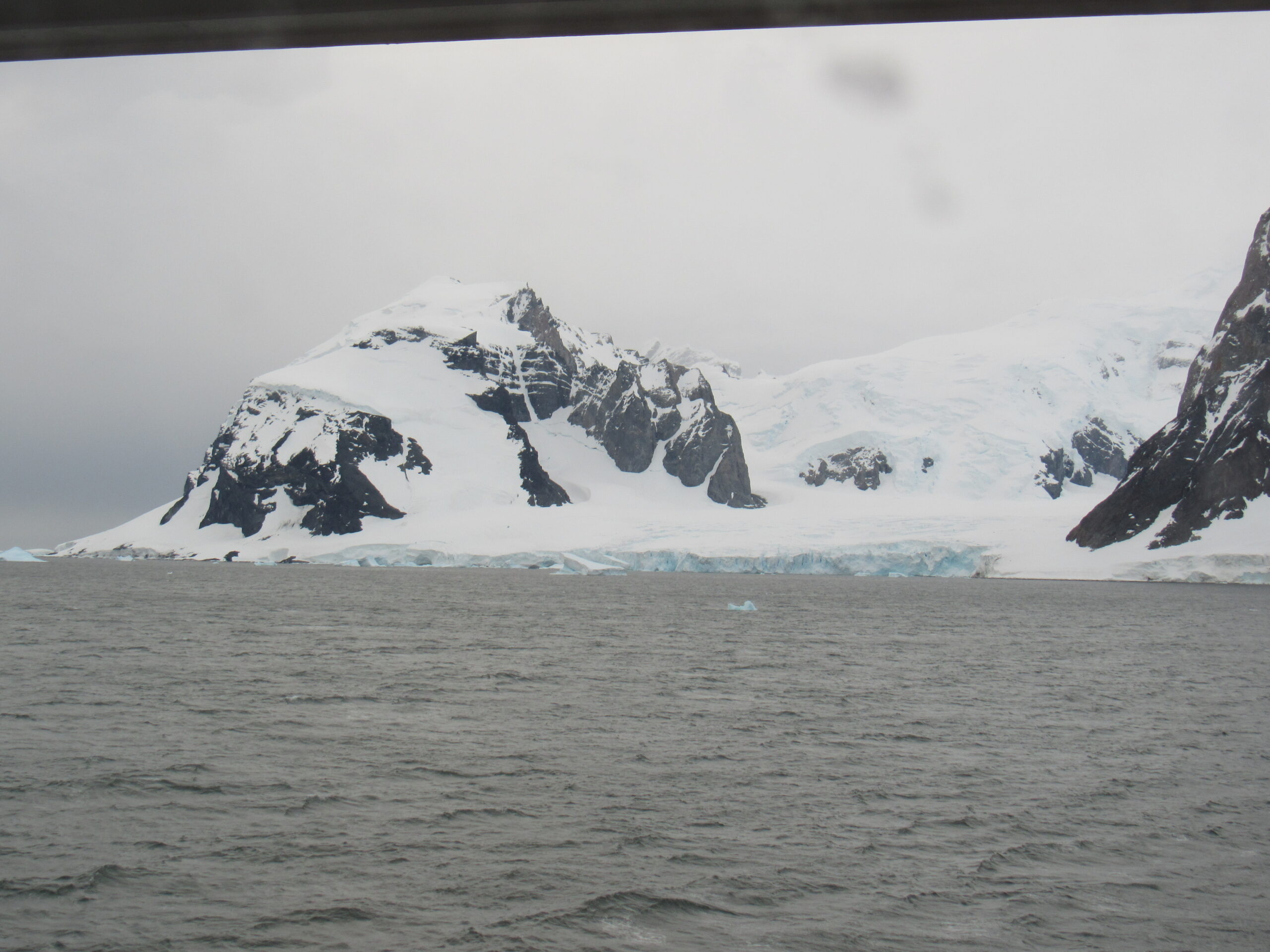

In the afternoon, some passengers took the Polar Plunge. In their bathing suits, they waded into the frigid ocean to be completely submerged, just to say they had done it. The medical team stood nearby to render aid if needed. Brrr, not me, not in a million years. It remained solidly overcast all day, and later in the afternoon we set sail once again. I took these next pictures at around 9:00 PM that evening. They show the southeast and south sides of Pourquoi Pas Island.

The island is 17 miles long by 8 miles wide, and very mountainous. It lies between Bigourdan Fjord and Bourgeois Fjord off the west coast of Graham Land. It was discovered by the French Antarctic Expedition under Charcot, 1908–10. The island was charted more accurately by the British Graham Land Expedition (BGLE) under John Rymill, 1934–37, who named it for Charcot’s expedition ship, the Pourquoi Pas. This next photo shows the thick ice sheet covering much of the island – it comes right down to the ocean – it was taken at 9:30 PM.

We spent the next few hours slowly cruising around, not covering much distance. We were out in Marguerite Bay, the largest such feature along the west side of the Antarctic Peninsula. It is bounded on the north by Adelaide Island and on the south by the Wordie Ice Shelf, George VI Sound and Alexander Island. To the east, the mainland coast on the Antarctic Peninsula is Fallières Coast, a part of Graham Land. Marguerite Bay was discovered in 1909 by the French Antarctic Expedition under Jean-Baptiste Charcot, who named the bay for his wife. The bay is big, 160 miles from north to south. The west side of the bay opens out on to the great Southern Ocean.

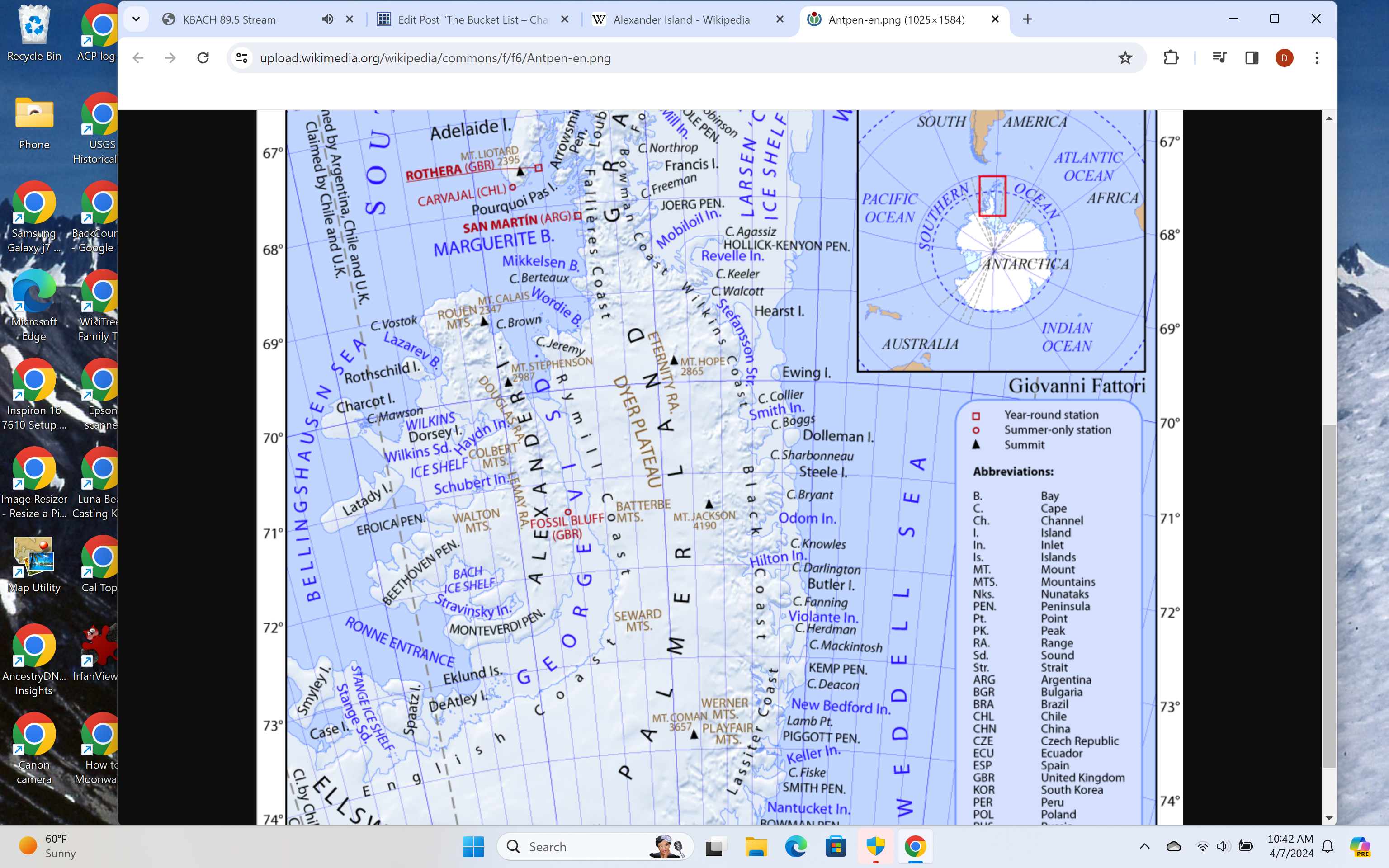

I mentioned Alexander Island, which sits on the south side of the bay. It is the largest island in Antarctica, and has some interesting characteristics. Do you know the name of the largest unpopulated island in the world? It’s Devon Island, part of Nunavut in the Canadian Arctic. But, the second-largest unpopulated island in the world is Alexander Island. This thing is huge, and oddly-shaped: almost 250 miles long, and almost that wide at its widest point, for a total area of 18,950 square miles – about the size of Maryland and Connecticut combined. Its highest point is Mount Stephenson, around 9,500 feet elevation. All the way up to 1940, it was believed that the island was a part of the Antarctic mainland and not an island at all. Aside from the higher peaks, the island is covered by a huge ice sheet. This far south, there’s not much ice melting going on. The fact that is was actually an island was proven in December 1940 by a two-person sledge party composed of Finn Ronne and Carl Eklund of the United States Antarctic Service. Along the east and south sides of the island sits George VI Sound, which separates it from the mainland – the sound is a 300-mile-long channel which is permanently frozen. It varies in width from 20 to 40 miles, and because its ice never thaws, it would be easy to think that the island was a part of the mainland. I’ve attached a map that illustrates all of this – the island sits on the left center part of the map, and the sound surrounds it to the right and below. You can also see Marguerite Bay to its north. Blow it up to better see the details.

Okay, I mentioned earlier that we were slowly cruising around in Marguerite Bay. It was still solidly overcast as the evening wore on. No matter how late the hour, even under cloudy skies there was plenty of daylight. These iceberg photos were taken at 11:15 PM.

The sky was getting brighter – maybe some clearer weather was coming.

Approaching midnight, the sun was getting ready to make an appearance – it’s still up in the clouds. Those are more icebergs out there.

The ship continued to move in a southwesterly direction, and the sky began to clear. I mentioned earlier that I would discuss the significance of the Antarctic Circle, and now’s the time.

Those of us who live in the northern hemisphere have heard the expression “land of the midnight sun”, generally understood to mean that in the far north in the summer it can stay light out all night, and if you’re north of the Arctic Circle you may even see the sun stay above the horizon all night. The same thing occurs in the southern hemisphere, but of course their summer is December through March. Aside from workers in a few research stations, nobody lives south of the Antarctic Circle, so if you want to experience the midnight sun in the south, you have to make the journey there. The timing is important, though.

The summer solstice in the southern hemisphere was on Thursday, December 21st of 2023. That means that if you stood on the Antarctic Circle (latitude 66 degrees 33 minutes 47.5 seconds south) on that day, the sun would dip down to the southern horizon but would not go below it, so it would not set. However, if you wanted to continue seeing the sun not set on the days after that, you would have to move a bit farther south each day to keep up with the phenomenon. In fact, you would have to move 3.94 miles each day to “keep up” with the sun’s not setting below the horizon. In my case, we were 130 miles south of the Antarctic Circle.

So here it was, the evening of January 12th, aboard my ship in Marguerite Bay. Little did I know it, but our captain was seeking clear weather and a sufficiently-far southern latitude for a special treat. As the evening progressed, skies were in fact clearing. I was in my cabin with the blinds wide open so I could see outside, and I noticed that the sun was still up. Then something magical happened. The sun sank lower in the sky, and came right down to the level of the ocean, but it did not set. It stayed there for a while, then started to climb higher into the sky. I was excited that I had stayed awake so I could experience this. The captain had moved the ship sufficiently-far south so that we could experience this special treat, at least the few of us who were still awake. I took this picture of the sun at its lowest point at 1:17 AM on the morning of January 13th, 2024.

The sun did not set!! See the distant mountains on the left side of the photo? They are on distant Alexander Island.

There is a website called Suncalc which allows you to accurately see the motion of the sun at any place and time, and here is how it looked at the time I took the above photo.

https://www.suncalc.org/#/-68.2699,-67.4163,6/2024.01.13/01:15/10/0

By plugging in the date, time and position of where I was, it shows how the yellow circle just touches the black circle. The sun dipped down to a point 0.43 degrees above the horizon, and there was 24h0m0s of sunshine, so I know I wasn’t imagining all of this. I knew before I started this trip that the captain would have to get us pretty far south this many days after the solstice in order to see the sun not set, and he came through. It may not seem like such a big deal, but to me it was one of the highlights of the entire trip. I finally turned in, with a big shit-eating grin on my face that you couldn’t have wiped off no matter how hard you tried.

Stay tuned for the next chapter of my Bucket List story.