Back in the year 1988, I had the good fortune to have spent a couple of months climbing up north, a good chunk of it in the Canadian Rockies. One day in early July, I was killing some time with my climbing buddies at the Columbia Icefield visitor center. While inside, we noticed some commotion over by the windows, so we sauntered over to check it out. There was a set of those large metal binoculars on a floor stand, the kind you might see at a tourist attraction such as the Empire State Building or Niagara Falls. Folks were waiting their turn to have a look, and we soon discovered why.

A young Swiss climber, maybe 22 years of age, was soloing the north face of Mt. Athabasca. He had already climbed up all of the steep ice and was about to climb through the rotten rock band below the summit. This was causing quite a sensation, and those in charge of the visitor center told us that the route hadn’t been soloed before, let alone by one so young. It was pretty impressive, watching him negotiate that difficult spot with no protection. If he had fallen, it would certainly have been to his death. Lars climbed the face solo, unroped, with no protection.

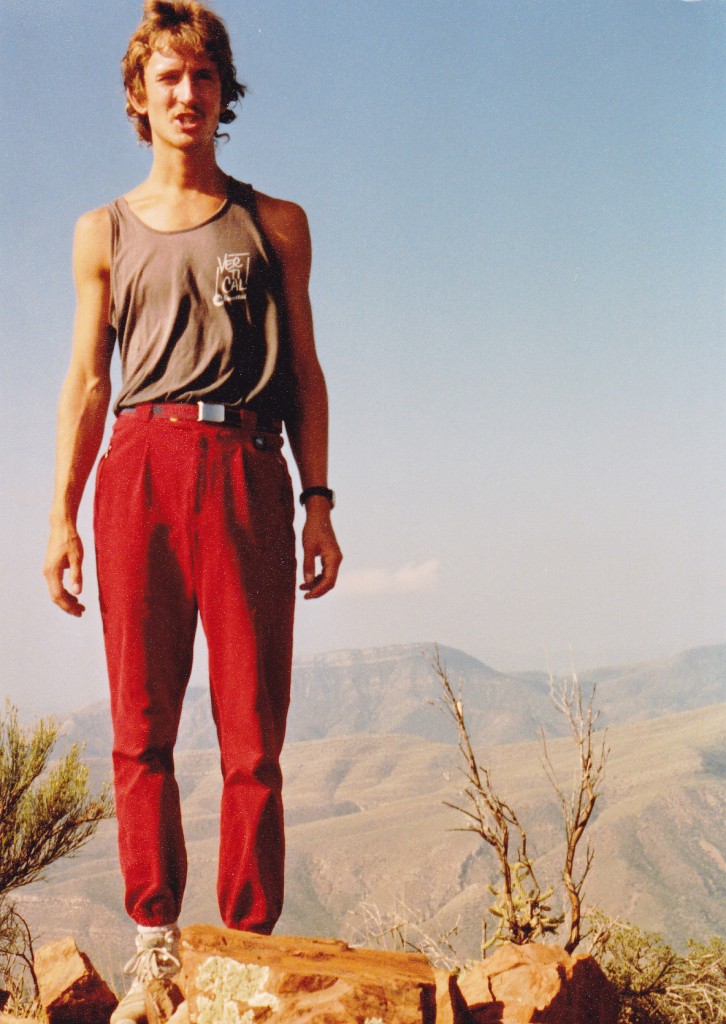

Later in the afternoon, once our wunderkind, Lars, had successfully completed his climb, we met him in our campground where he too was staying. He was an instant celebrity, and we all wanted to learn more about this climbing prodigy. It turned out that in his native Switzerland, he had already compiled quite a résumé on both rock and ice. He had even made two trips to Denali. On the first, after he had summitted solo, he was caught in a storm at the high camp at just over 17,000 feet. Three days later, after the storm had passed, he emerged from his snow cave to find that three British climbers with whom he had spoken as the storm hit were all dead. They had not survived in their tent.

On his second visit to Denali, he had soloed the Messner Couloir, an outrageously dangerous route known for its rockfall hazard, en route to the summit. It was only the third time it had been soloed. A couple of months after having met him, I got a phone call from Lars. I was back home in Tucson and he was on his way to visit me. It was great to see him once he arrived. He had bought a beater Chevy Surburban once he had entered the U.S. and was using it to travel around, climbing his brains out. It was late August when he showed up at my door, and still plenty hot. We spent several days rock-climbing at Windy Point up in the Santa Catalina Mountains near town, but Lars wanted to see some of Arizona’s back-country. I suggested we do some peak-bagging.

I was still working on the completion of a big project, climbing the high point of each of Arizona’s mountain ranges. With many still left to do, there was no shortage of peaks we could go and bag, so away we went. The Natanes Mountains and the Hayes Mountains highpoints were the first two we visited, and they went without a hitch.

We then visited the Gila Mountains near the town of Safford. After a start which was rather late in the day, we tackled Bryce Mountain. Lars was skeptical of our making it back to my truck before nightfall. I made a bet with him, a Black Forest cake being the wager, that we would in fact make it – and we did.

A few miles away, we found a large tank (a man-made pond for watering cattle), where we stripped naked. Even though the muck on the bottom of the pond was calf-deep, the cool water felt great after a hot day of climbing.

The next morning, very early, we drove many miles to eventually park at a place called Goat Camp, some miles southeast of our next summit. Mount Turnbull was the high point of the Santa Teresa Mountains, and a worthy objective in the heat. Our monsoon season was still active, and during the course of a long day, we dodged three different thunderstorms. One thing still stands out in my mind during the long descent back to the truck. Lars’ command of the English language was quite good, but he was eager to improve it. He was fascinated by the myriad ways we use the word “shit”. I recall explaining to him, among other things, what we meant by “shit out of luck”. I guess he didn’t quite capture the nuance of it, and here’s how I know. Weeks later, after he had left Tucson and was motoring along some desolate highway in Nevada, his Suburban’s engine seized up and he had to just walk away. He wrote to tell me that, upon learning the bad news, he realized that he was “a shit out of luck”. I still chuckle over that one.

A week after Turnbull, Lars wanted tastier fare, so we decided to go try Baboquivari Peak. He asked me how difficult it was – I told him that depended on who you believed, but somewhere between Class 4 and low 5th. He said that that would be no big deal and we should just go. We drove the dirt road up Thomas Canyon and parked at the old ranch house southeast of the peak. The idea was to climb by the Forbes route, and away we went. Before we knew it, we stood in the 6,400-foot saddle northeast of the summit. Lars inspired a lot of confidence. He had spent hours telling me about his climbs in the Alps, and I had learned that he climbed to Class 5.10 in heavy mountaineering boots, the kind you’d use with crampons. We cruised through two short areas of rock and then, before we knew it, stood at the base of the crux, the Ladder Pitch. The holds were good, as was the rock itself, and soon we were past that and on the summit. It was good to finally be there. I’ve gotta say, though, that I about soiled myself downclimbing the Ladder without a rope. I doubt I’d ever try that again – in fact, I know I wouldn’t.

Lars left Tucson soon after Babo. I never saw him again, and that was 25 years ago. I know he had big plans, including 8,000-meter peaks, but I don’t know how any of that turned out. He was one talented climber, and, short of being hurt or killed, I have no doubt he could have accomplished anything he set his mind to.

Epilogue: I have re-discovered Lars! He is alive and well, happily married and living in his native Switzerland. A serious cycling accident some years ago put an end to his extreme climbing, but he and his wife still get out to enjoy the mountains as often as their professional careers allow. It has been good to re-connect with him.

Please visit our Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690