Bluebird Pass – it’s not on any map, but it’s well-known to both Border Patrol and Bad Guys alike. I should qualify that – the name isn’t on a map, but certainly the topography is. Undocumented border-crossers, led by their coyotes, come up from Mexico and make a beeline for it, trying to get through it to the town of Ajo. Once there, they wait for their ride to Phoenix, in the hope of blending in forever. I’d heard about it for years, so now it was time to satisfy my curiosity and see it for myself. Besides, the pass was a perfect spot from which to climb three nice peaks I needed. It’s got one hell of a reputation, and not a good one, because of its strategic location. The pass is an out-of-the-way back door to reach the town, far less obvious a route than hugging the main roads. I’d been warned to stay away from it, due to the high probability of running into Bad Guys. The people doing the warning were good folks in the Border Patrol who didn’t want me to regret going in there. I thought about it for a good while before I decided to head on in anyway- the peaks were calling.

It was late on a warm afternoon when I arrived in the area, and almost sunset by the time I’d found a good camping spot. Near the old Bluebird Mine was something marked on the map as the Bluebird Mine well, no doubt for the use of the miners back in the day – I camped near there. Once set up, I hunkered down and prayed for the most quiet, boring night of my life. Smugglers move through the desert under cover of darkness to minimize detection, and here I was, more or less in the main line of travel for anyone coming through the pass. After several restless hours, I arose and packed up my gear, marking its location by GPS and hoping it was well-hidden.

There was an old road near my campsite – at around 5:15 AM, I walked it east and followed it down into a deep, sandy wash, which I then followed north. The waxing gibbous moon had already set, so it was very dark – I had to use my headlamp. The amount of deep, soft sand in the wash would make it difficult to drive up it. The rocky walls lining the canyon in which the wash sat were close in at times, and the canyon changed direction with abrupt serpentine curves. It was an eerie place in the dark, and I was pretty paranoid of running into smugglers. As the canyon climbed north, it steepened, and what had been an old road climbed out of the sandy wash and up a steep hill. The road, such as it was, had been deeply eroded with a V right down its middle. I pity the fool who tried to drive up it and made the slightest mistake and ended up with his wheels in the V.

As I reached the pass, at 1,700′ elevation, there was enough light to see, but barely. I could now turn off my headlamp and make a hard turn to the southeast and start up the slope of Scarface Mountain. elevation 2,546 feet. It was easy going, just a matter of dodging the cacti en route. A bit of enjoyable scrambling near the top finished off the climb. On the summit, I found a can, painted red, which I immediately recognized as one of Rich Carey’s. Rich sandblasts two cans that nest inside each other, and paints them with the most durable paint money can buy, his trademark red. A glass jar with a tight-fitting lid sits inside of it all, protecting the paper and pencil which is used to record the ascent. It is truly a register for the ages, and can last for decades. The excellent Lists of John website documents the fact that Rich left the register back in 2001, but smugglers had been there in the intervening years and had messed with it – all that remained was one red can.

It was 6:30 when I reached the summit. The sun had just risen, and I had this great view of Bates Benchmark, a peak I wanted to climb soon.

It was 6:30 when I reached the summit, and after a short while there I started down and took this photo lower on the northwest slope.

By the time I got back down to Bluebird Pass, I walked into the sunshine and crossed the old road. It was a quiet walk up a valley, then a climb up a limestone hillside. Near the top, I heard bees buzzing, but it was already too late to avoid them. I realized that I was standing right in their flight-path, right in front of the crevice in the rock inside which they lived. A few smacked into my legs, and I knew it was a warning, a signal to get out of there quickly – so I did. Close calls like that are especially dangerous when you’re alone. I hustled up the southeast ridge of this mountain, and found myself doing some route-finding at the top, clambering up loose stacks of large plate-like rocks. The summit was open and airy, and it was good to be there. Nine folks had signed into the register, including one from Mexico. It was eight o’clock when I arrived on this summit, Peak 2242. After the requisite photos, I decided I’d better start down. – I’m always a little jumpy when I’m alone and need to downclimb something tricky to get off a summit on to easier ground. It all worked okay, though, and I made it to the valley bottom on the peak’s west side.

The morning was still fine, not too hot, so I continued on south. Here’s a view of Point 2292 as I approached it, then climbed up past it on the west. From there, it was an easy climb up on to a ridge, which I followed around in a big horseshoe to reach the top of Peak 2591. I’d made good time, it was just before ten.

At the risk of sounding repetitive, the views were amazing, but hey – these were the Growlers.

There was no register on this one, and I left it that way. Making my way back over to the horseshoe ridge, I then dropped 400 feet to a saddle, gambling that I could drop down from there and head east back to my gear. It didn’t take long to get all messed up in a bunch of rotten cliffs, but it turned out okay. Here’s a good view looking east to Scarface Mountain, my first of the day.

Several gullies later, I was back at my gear, where it was as I’d left it, unmolested. Here’s what was left of the well that had been used for the mine.

Since I was so close, I thought I’d go over and check out the mine itself. When I got there, I found the mine entrance surrounded by a sturdy fence.

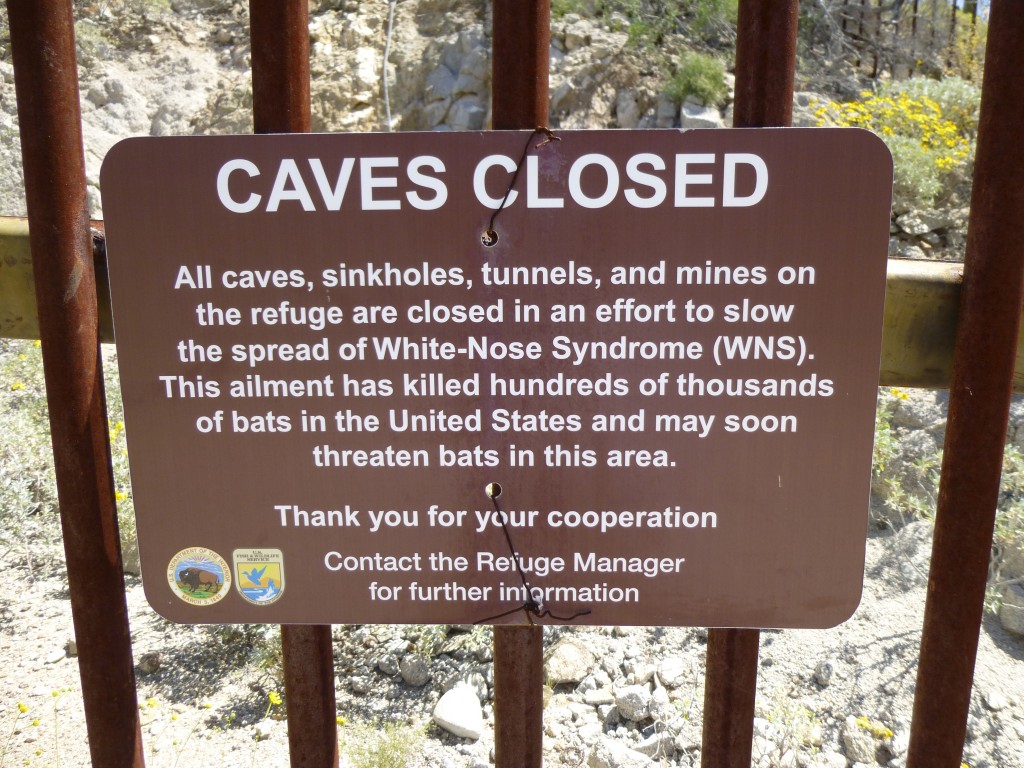

The mine sits in the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, and they’d put signs like this on the fence.

It wasn’t even noon by the time I’d finished poking around the mine, and barely 1:00 PM by the time I’d returned to my truck down on the Camino del Diablo. With that much of the day left, it only made sense to climb something else. There was another peak close at hand, so I drove over to Bates Well and parked.

I’d driven past Peak 2390 dozens of times over the years, but had never stopped to climb. Today was the day. It’s 1,800 feet in a straight line to get across the vegetated nightmare that is Growler Wash if you start at Bates Well. News flash – you’ll never make it in a straight line. After some serious cursing, I was through and stood on the lowest part of the slope.

It was a funny climb. The first 750 feet took me up to a narrow ridge, where the stiff breeze felt good. Another 200 vertical feet of climbing brought me to a place where the ridge broadened to a wide, easy plateau. Half a mile ahead, I could see what looked like the summit, sort of. It was very flat. When I got to what looked like the highest point, I wasn’t sure. Once in a long while, a summit is so flat that a proper peakbagger will have to spend a while looking for the very highest point. Back and forth I went, getting a perspective from several places. Hard to tell. Keep walking. It was so flat. I did the best I could, and finally decided on one spot and built a cairn. It was three o’clock.

It didn’t take long to make my way back north off the plateau and on to the narrow ridge. As I started down the steep slope to the desert below, I heard a sound that caught my attention. It’s so quiet out here that anything out of the ordinary grabs you. It was faint, but I zeroed in on it. Two and a half miles to the northwest sat Bates Benchmark, one of the larger peaks in the area. It seemed like something was going on over there. Then I saw it, a helicopter circling around the summit, slowly and deliberately. I stopped and watched it several times on my way down. Why did I care? Because tomorrow I planned to climb it, that’s why. It must have spent a full 15 minutes up there, then finally moved off.

When I reached the bottom of the slope, I decided to head east along a big loop of the wash, towards the entrance to Growler Canyon.

The tire tracks had been left by Border Patrol and also smugglers. Although it cost me an extra mile, it sure beat the bushwhack the way I had come. It was almost five by the time I reached my truck. Still needing to find a place to camp, I headed east on the Camino and soon met up with a B.P. agent in his SUV. We stopped in the middle of the road, blocking it nicely, and talked. I told him how I’d seen their chopper flying around the peak and asked him if he’d heard any chatter on the radio about what was going on. I told him I was planning to climb it in the morning and was going to be a lot more concerned about it if there were Bad Guys up there. He said he hadn’t heard anything, but probably they had spent that much time up there because they were trying to scare some smugglers away from the peak, no doubt a lookout point. Well, that didn’t exactly make me feel any better about what (or whom) I’d find up there, but I guess I’d just have to find out. Even this great sunset didn’t put my mind completely at ease.

By 5:30 AM, I had moved several miles down the road, parked and started on foot. The headlamp was needed for a while as I walked north, but a mile short of and 1,100′ below the summit, I had turned it off. The whole south side of the peak was a jumble of boulders and small cliffs. As I started to climb, I was thinking of drug-smuggler lookouts sitting up top and seeing me, so I put my plan into action. Calling out in a loud voice, I pretended there was more than one of me, making it sound like I was with someone else and we were shouting back and forth as we climbed. I figured that at least that way they might get scared into leaving the mountain-top and I’d have the place to myself. Near the top, I saw these two sitting quietly and watching me climb.

As I climbed up a steep ramp, I heard a telltale sound on the cliff above me – bees. It must have been a large hive, as there were a lot of them moving in and out of the crevice in the rock. I went out of my way to avoid them and soon stood on the summit ridge, which I followed to the top. It was only 7:15, and there was nobody in sight. However, there was trash everywhere – obviously smugglers spent a lot of time there, watching the movements of Border Patrol vehicles on the Camino to the south. The register was gone, and I didn’t leave one – it’d be wasted, as smugglers would soon dispose of it. I was relieved that I had the place to myself, that I didn’t have to confront any Bad Guys. Bates Benchmark, elevation 2,610′, was the highest peak in the southernmost group of the Growler Mountains.

Okay, what next? Actually, I knew exactly what was next – this one, 3,000 feet away and about 400 feet lower.

The only issue was getting over to it. I walked over to the edge and peered over – too cliffy. It looked like, if I went back down the summit ridge a ways, I might be able to drop down into the basin I’d climbed, on the southeast side. My goal was to get over to the prominent south ridge, and from there make my way down to the saddle between the two peaks. It turned out to be a lot more challenging than I hoped. A diagonal traverse over to the ridge involved dodging a lot of cliffs, and when I finally got there, my way down was blocked by even more cliffs – that’s common in peakbagging – you have to make decisions on the fly all the time. This forced me to find a way down to the west off of the ridge, and I was sweating bullets – there was a lot of route-finding through steep, loose terrain.

When I’d dropped down to around 1,800′, I heard a familiar sound. It was a Border Patrol helicopter, not a quarter of a mile away, heading east – it circled at my altitude a few times, looking for something. It didn’t spot me, although I was out in the open and waving. It soon left and I dropped a few hundred feet lower, crossed two gullies and was at the foot of my peak. The climb up the west ridge was exhilarating, on good granitic rock – I was there by 9:15. Smugglers had been all over Peak 2230 – their trash was everywhere, but the register had been removed from this one too.

I finally had a front-row seat for the peak I’d just laboriously descended – that’s it on the left. The south ridge is the one coming straight towards you from the summit.

Since I was going to descend from here by a different route, I wanted to get started. There was plenty of steep ground filled with caves on the way down, and it wasn’t boring.

An hour after I left the summit, I was back at my truck. It was only 10:30 AM, but I was glad to be done – it felt hot and muggy and it was time to head home. As I headed back east towards the town of Ajo, it occurred to me that if I climbed one more peak, just a little one, I’d finish off the entire Bates Well quadrangle. By the time I parked at the base of Peak 2141, it was 11:30 and an unseasonably hot 95 degrees F.

It was a quick climb up to the ridge, but after that things got interesting. A steep scramble up the skyline took me to the crux of the climb. I’ve drawn a line on the final part of the route.

See where the line drops down? That’s where it got exciting, because after you climb down and then start back up to the right, you are on an exposed ramp that leans outward away from the cliff. I found it a heart-thumping experience, but was soon on the summit. There was actually a register with several prior entries – this didn’t surprise me, actually finding a register, because there’s no way that smugglers would want to tackle a tricky climb like this one (and they’d be the ones to destroy a register). By the time I got back down to my truck, only an hour had passed, but this time I was truly done. It had been a great two days of climbing, and I know I’ll look for excuses to get back to the area.

Please visit our Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Desert-Mountaineer/192730747542690