In southern Arizona, there’s a road known by few, driven by fewer. Those of us who have ever had any experience with it usually refer to it as the pipeline road, but it could be more properly called the El Paso Natural Gas Pipeline Road. For all intents and purposes, it runs from the village of Vaiva Vo (“Cocklebur” in English) and heads westward across the Tohono O’odham Indian Reservation.

Over the last 35 years, I’ve driven on bits and pieces of it, each time associated with climbing a peak or two. I had driven every inch of it at one time or another, several times over, but I couldn’t recall a time when I had purposely set out to drive the entire length of it in one push. So, with Covid 19 rearing its ugly head again, this time with the Delta variant, it seemed like a perfect way to spend a day, just me in my truck with no one else around, driving along the pipeline road.

I started by driving 85 miles on freeways to reach the Stanfield exit on I-8. Four miles south from there takes you to the reservation boundary, where I guess you could say that Indian Route 42 officially starts. Once you’re on 42, it’s only 4 more miles to the village of Vaiva Vo. That’s how we say it in English, but the proper name in the O’odham language is Waiwa Wo’o, which means “Cocklebur Pond”. The village is home to 165 people. Route 42 only goes another 19 miles before ending at the major Indian Route 15 near North Komelik, en route passing the hamlet of Kohatk (Kohathk in the O’odham language, which means “hollow”). Kohatk only has 80 people. Vaiva Vo is really the starting point of our journey.

The paved highway makes a distinct loop to the east by Vaiva Vo, but right where it comes back out of it, an unmarked dirt road veers off. It runs parallel to the pavement, only a hundred feet away, for about a mile. I thought it might be fun to show our journey as a mileage log as we move along.

0.0 miles – leave the pavement 8:08 AM

Almost immediately, we see markers advising us that we are following the pipeline. These markers must start some miles to the northeast, near the city of Casa Grande, and well off of the reservation.

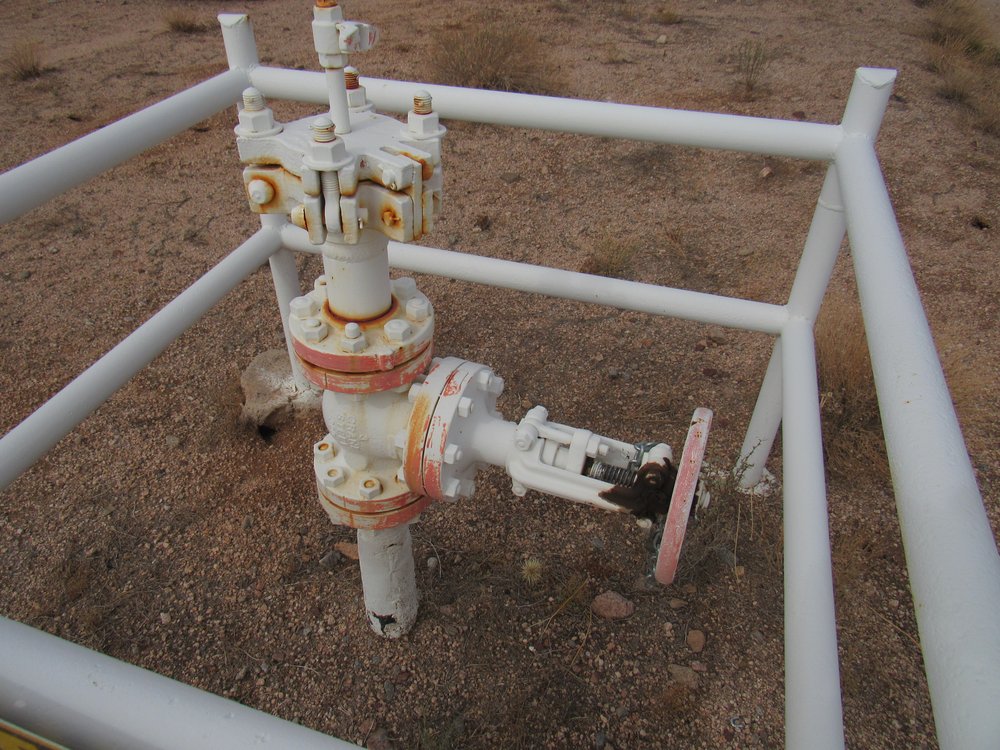

The pipeline is buried alongside the road. Once in a while, I saw one of these things.

The road veers away from the paved highway after about a mile and heads out into the desert. If we look to the northwest, we can see Indian BM, the high point of the Vaiva Hills at 2,561 feet.

1.6 miles – Indian Benchmark 8:23 AM

The first real feature that crossed the road was Mesa Wash.

3.7 miles – Mesa Wash 8:35 AM

This is a good look at the road, still wide, level and straight.

I soon came to this thing – no idea what it was. The topo map shows another pipeline heading southeast from here for 14 miles. It is above-ground, and ends at the now-closed copper mine by North Komelik.

4.5 miles – unknown equipment 8:40 AM

This next thing was a surprise. A tiny building, which had power brought to it on an overhead line. The line would have come in many miles, and just for this. I could hear some kind of equipment operating inside it. I had not a clue what it was, but no doubt it had something to do with the pipeline.

6.2 miles – tiny building 8:51 AM

In this next picture, we are looking southwest to the high point of the Vekol Mountains, simply known as Peak 3609. It has over 1,500 feet of prominence.

A short distance later, I encountered this – a set of valves. I’ll bet they are there to shut off the pipeline in case of emergency.

The one farther away had a masonry enclosure built around it – here’s what the inside of it looked like.

Each valve had a flimsy chain with a lock on it.

9.1 miles Valve station #3 9:10 AM

I was approaching the northern end of the Vekol Mountains, seen here as Point 2422 just left of center. There were many large puddles like this one, a result of recent monsoon rains. From time to time I would pass a faint dirt road heading off either to the north or south from the pipeline road. These invariably went to man-made tanks, bulldozed into the desert to create a place for water to collect after a rainstorm. They are there to provide water for cattle.

10.2 miles big puddle 9:20 AM

From time to time, I would see piles of donkey poop like this. Many donkeys live wild and roam freely on the reservation.

The O’odham raise plenty of cattle, which also seem to roam freely, like this guy.

Some didn’t fare as well as he, attested to by this skull and ribs.

See this next photo – there’s a distant peak just to the right of center, about 4 miles away to the north. That’s Black Mountain. Just below it and running towards us is an obscure feature known as Table Top Valley.

11.8 miles Table Top Valley 9:38 AM

From the same spot, I had this view of Little Table Top (on the left) and Table Top on the right. It’s a rare view to see them together like this.

To the south of the road sat a mountain known as Bitter Benchmark. It was 9:44 AM here.

Now I would begin to cross the Vekol Valley. This broad valley is about 9 miles wide, and in this photo we are looking northwest. Those are the Sand Tank Mountains in the distance.

13.2 miles The Vekol Valley 9:49 AM

The Tohono O’odham Indian Reservation is about 2,800,000 acres in area, or about the size of the state of Connecticut. The majority of its lands were set aside in 1916. Before the creation of the reservation, there were some privately-held mining claims on those lands. Four of those pieces of land are found within the Vekol Mountains. Two of them are on the east side of the range – the Christmas Gift Mine and the Reward Mine. As long as those claims are worked enough to consider them active, they can continue to be privately held. The T.O. Nation allows them access across Indian lands to access their claims. Two more such pieces are found on the west side of the range – the Copperosity Mine and the Vekol Mine. The first 3 have long sat idle, but the Vekol Mine has had a watchman living on the site for years. He is very protective of the site and runs off any would-be visitors. Here is the road which heads south for about 2 miles to the mine.

14.0 miles Road to the mine 9:55 AM

The next thing that hove into view was this view of the Copperosity Hills to the south.

Mile 15.3 Copperosity Hills 10:03 AM

The road went straight as an arrow all the way across the Vekol Valley, about 9 miles. In this next stretch, I crossed from Pinal County into Maricopa County, although you’d never know it.

Before long, I came to another of those little buildings.

15.9 miles Little building 10:10 AM

It had electrical power, as I could hear equipment working inside it. However, there was no above-ground power line – how was it powered?

There was a metal tag fastened to the building, showing the name of the company that had manufactured it. I Googled them and called their office in Houston, Texas. A fellow there was very happy to chat with me. I sent him my photos and he filled in the blanks. If you go back 2 photos to the little building, you will see a pipe the same color as the building rising up out of the ground on the end of the building nearest to us. That pipe taps directly into the buried pipeline across the road. It brings gas into the building which runs a generator. The generator provides electrical energy to the white boxes outside the building. Through a process I didn’t understand at all, he said that those white boxes have something to do with preventing corrosion on the outside of the pipeline. Most of what he said went right over my head.

I could see, back to the northeast, the Table Top Mountains and their 12 peaks. In this view, they are about 5 or 6 miles distant.

15.9 miles Table Top Mountains 10:10 AM

Coming up was Thorn Benchmark, the southernmost peak in the Sand Tank Mountains.

17.6 miles Thorn Benchmark 10:21 AM

At 19.2 miles, I drove up and over a low ridge marking the southernmost point of the Sand Tank Mountains.

As I proceeded, I could see something big and white ahead.

I had reached Kohatk Wash, and here the pipeline was suspended in the air.

19.8 miles Kohatk Wash 10:37 AM

Soon after, I came to what I’m calling valve station #4, just like #3 eleven miles back.

Just ahead, there was a gate, unlocked. It looked like it hadn’t been used for a long time. Anybody who had come this far would probably just drive around it if they found it locked.

There was an old, rusted sign on the gate. In the past 35 years, I’ve never known of any locked gate along the pipeline road.

Mile 20.0 The gate 10:40 AM

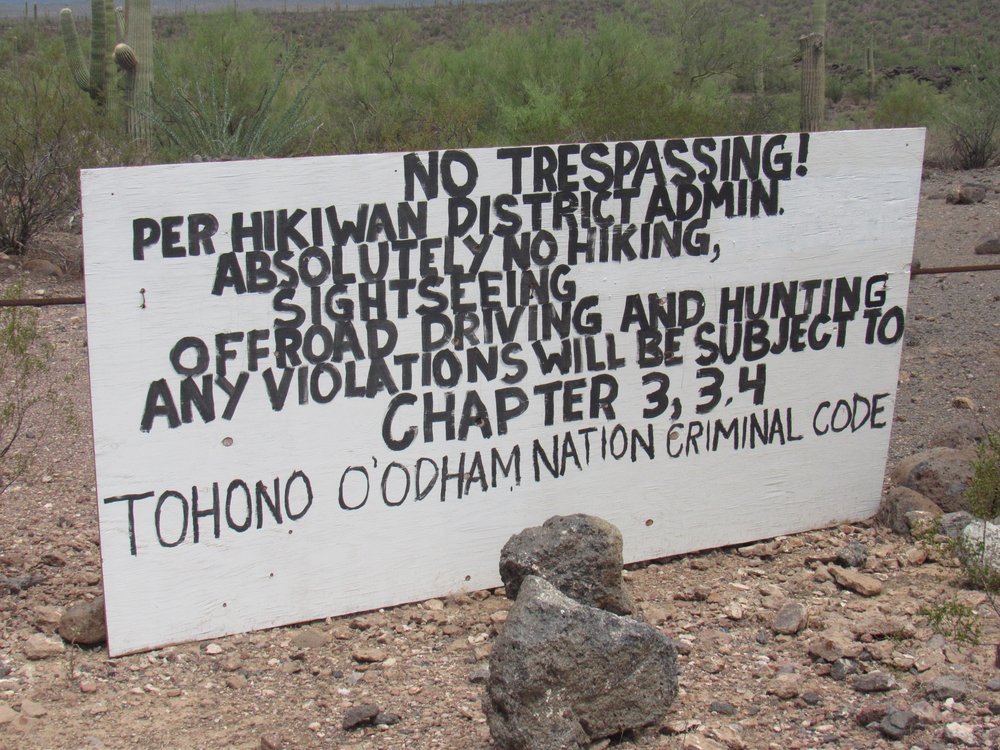

A couple of miles later, I got my biggest surprise of the day – this sign was impossible to miss.

This sign had been placed beside an old gate, only 2 miles away from the village of Kaka. I was a bit surprised to see it here, as I had actually been driving on the Hickiwan district for several miles already. This was the first time I’d seen such a sign on the reservation. Were they tightening things up because of Covid, or just not wanting any outsiders crossing their land?

Mile 22.5 The gate and sign 11:01 AM

Less than a mile later, I came across my third little building of the day – it looked just like the other two.

This was across the road. Poor beast, it may have died in our recent heat wave. Such a shame, it was right near the edge of the village of Kaka.

I had arrived at the village of Kaka, population 140. It’s proper name in the O’odham language is Gagka, which means “clearing”. This is the only community that one encounters along the entire length of the pipeline road. The road skirts the northern edge of the village. A paved road reaches Kaka from other communities inside the reservation, but that paved road ends here.

Mile 24.7 Kaka 11:17 AM

At the western edge of the village sits their cemetery, the final resting place of about 400 souls.

Mile 25.6 Kaka cemetery 11:22 AM

As we continue to the west of Kaka, we encounter the only place along the pipeline where the location of the road is ever in doubt. That’s because for about 2 miles, the road squeezes between some low hills. Normally, that wouldn’t be a problem, but Kaka Wash runs through that same space and really plays hell with the road, completely wiping it out in places. Those 2 miles are by far the roughest road we’ve encountered so far. Here’s a spot where a large pond has formed. As we pass through the wash, we also travel from Maricopa County into Pima County, where we remain for the rest of our journey.

Hey, remember some time back I mentioned the wild donkeys? Well, here are 2 of the prettiest you could ever wish for.

Mile 26.5 Donkeys 11:40 AM

When we finally emerge from the channel of the wash, we find ourselves in an open, flat piece of desert once again, sitting squarely in the middle of the Kaka Valley. If we look northwest from the road, we look up the valley and can see 2 mountain ranges in the distance. On the left are the Sauceda Mountains, and on the right are the Sand Tank Mountains – the valley acts as a natural dividing line between the two ranges.

The next thing we come to is Valve Station #5, and it was noon. I had been driving along the pipeline road for 4 hours now. In the distance, the road climbs up a steep hill. There, the road was pretty rough. You might make it in 2WD, but the smart money would be to try it with a 4WD and high clearance.

Mile 29.4 Valve station #5 11:59 AM

From atop the hill in the previous picture, I had this view, looking south, to Cimarron Peak, the highest along the pipeline road.

Mile 29.9 top of rough hill and view to Cimarron Pk. 12:04 PM

From the top of the hill, I had this view west to Toapit Benchmark. It’s the one on the left side, on the skyline, almost 3 miles away.

Once down off the hill and on to the flats again, I soon came to this thing.

31.0 miles Pump by Cimarron Peak 12:14 PM

A bit later, while driving down a rough section of hill, I saw that the pipe was lying open and exposed on the ground, rather than being buried – not sure why.

And right across the road from the pipe was this wrecked truck. It’s been there for years. All of these vehicles which have been abandoned on the reservation were stolen, and used to bring either people or drugs into the country illegally. They either break down or they crash while trying to escape law enforcement. Believe it or not, at one time there were 3,500 of these on the reservation; now they have nearly all been removed.

Mile 32.4 Truck 12:27 PM

Here’s yet another way they had to suspend their pipe, this apparatus being taller and stronger than the others I had encountered.

Just as I entered the very flat Hickiwan Valley, I passed this road – it turns off to the south and goes to the village of Hickiwan, about 7 miles distant.

One mile beyond that turnoff, I passed another which heads northwest to the village of Stoa Pitk. Census figures from 10 years ago say that there were 25 people living there, but I just don’t see it. There’s no electricity, no running water, no vehicles parked there. I think everybody just up and left.

A few miles farther on, we cross Hickiwan Wash, another spot where the pipe is completely exposed.

From there, I had a clear view over to Peak 3930. Back in 2006, I climbed this peak in the company of a dozen friends. We were celebrating my list finish of the 401 peaks on the Tohono O’odham Indian Reservation.

Nearby, I found these stone walls. They had been pretty substantial back in the day, but were now all busted up. Perhaps they had something to do with impounding water.

At the same place, I found this signage.

And this benchmark. Surveyors leave these as they move across the land and do an initial survey of an area. This one is a brass plate set in concrete, and signifies an elevation of 2,379 feet above sea level.

The next photo shows how the road has been completely washed away. You can see my tracks off to the right to bypass the spot.

Mile 37.2 Road washed away. 1:06 PM

Here’s a photo of Old Faithful, my 1988 Toyota 4WD pickup. Not much to look at, but she runs well and never leaves me stranded.

I came upon another of those valve stations out at the west end of the Hickiwan Valley.

Mile 37.7 Valve station #6 1:11 PM

Finally, I left the Indian reservation. From just outside the boundary fence, there was another of their big hand-lettered signs leaning up against the gate. In this photo, we are looking east, as if we were about to drive into the reservation. That’s looking back the way I had just come.

The gate was not locked, and I don’t know that it ever has been – certainly not in the 35 years I’d been driving the road. Although the reservation is private land, and they could lock the gate, in the meantime giving El Paso employees a key, they’d also need to give the Border Patrol a key, and who knows how many others. It’s hard to say how many would drive through here in a day, a week, a month.

Mile 39.6 Leaving the reservation 1:28 PM

As soon as I passed to the west of the sign, I was out of the reservation and onto BLM land. This sign showed I was still on the pipeline road, which was now called Road #8100.

The next mile was an easy one, taking me to the crest of a small ridge at 2,630 feet. There, the road split – the branch that followed the pipeline was scary-steep, while an alternate branch was gentler. After some ups and downs, I reached a saddle at 2,609′. From there, I could see ahead half a mile across a canyon to where the 2 branches joined again. It was rough going to that junction.

From the junction, a few tenths of easy road led me to another ridge at 2,740 feet elevation, then another 6 tenths that was fairly level and manageable to another ridge at 2,814 feet. This was the highest point along the entire pipeline road, in the heart of the Sauceda Mountains. What happens next will put the fear of God into anyone. You’d better have high-clearance and nerves of steel. I’ve been driving this stretch of the pipeline road for over 30 years, and it just gets worse every year. There’s no such thing as any kind of maintenance on it – all trace of soil is long gone, and what’s left is bare rock, and when I say it’s rough – well, I’m not shitting you. I crawled down the long, steep hill in 1st gear, low range, working the brake and clutch the whole way, using all my skills. You have to watch every inch of where you’re going, making sure where your wheels are at every moment. Go as slowly as you like, you’re still going to bounce around the cab of your truck like a ping-pong ball. Better to roll down your window so your head doesn’t smash into it. Once, try as I might to avoid it, I bounced so hard that my head hit the roof of the cab and I saw stars. I’ll bet I didn’t even manage half a mile-per-hour driving down the 400 vertical feet of that hill. I was expecting it to be bad, but it exceeded all of my expectations. You’ll never find me trying to drive up that hill. At least there was a nice view of Coffeepot Mountain when I was done.

Once down on easier ground, I arrived at another of those pumping stations, working merrily away.

Mile 43.8 Pump station 2:09 PM

The going was easy now. A few miles more brought me to Valve Station #7.

Mile 47.5 Valve Station #7 2:26 PM

Burro Gap was next, a 600-foot-wide opening where the road passed through the Batamote Mountains. I crossed Ten Mile Wash no less than 3 times in that area.

Mile 47.9 Ten Mile Wash 2:29 PM

Through Burro Gap, the road continued west across the very flat Valley of the Ajo. Everything there was flat, even Sikort Chuapo Wash.

Mile 53.3 Sikort Chuapo Wash 2:54 PM

The last landmark I passed was this, Darby Arroyo.

Mile 54.2 Darby Arroyo 2:59 PM

I was fast approaching the end of the road. After passing through one last unlocked gate, I had this look back east, the way I had come. The mountains in the distance are mostly the Saucedas, about 15 miles away.

Mile 55.8 A look back from the final gate 3:10 PM

The pipeline road ends at Arizona Highway 85, on the east side of the town of Ajo. There’s no doubt the pipeline itself continues, buried and running who-knows-where. For me, though, the journey was over. Mountains of waste rock from a century of working the open-pit New Cornelia Mine towered above the roadway. This was the first copper mine in Arizona.

A monument sits at the end of the pipeline road. It marks the site of an early mining encampment known as Clarkstown that existed before 1916, then burned down.

Mile 57.0 The monument 3:18 PM

Well, I was done. The 57 miles had taken me 7 hours and 10 minutes to travel. I only stopped to take pictures and nothing else, so that worked out to an average speed of 8 miles an hour. I’m glad I did it, but I won’t do it again, that’s for sure.