Most everybody has heard of a raindrop, a dewdrop, a teardrop, a backdrop, an eyedrop and a gumdrop. We also know the term “eavesdrop”, but how many are familiar with the word “airdrop”? Basically, the word means to drop something out of an aircraft down to the ground. As I further explored the term, I learned that there are different types of airdrop, depending on how they are done.

One type is a low-velocity airdrop, where whatever is pushed out of the plane is attached to big parachutes. The idea is that those chutes will allow the payload to hit the ground with a very minimum of force so it will remain as intact and unharmed as possible. This type of airdrop is used for more fragile items, such as soldiers jumping out of planes or cargo that is fragile. A second type is known as a high-velocity airdrop, where parachutes act mainly to stabilize the payload’s fall but not cushion it so much, and this is used for more durable items such as supplies. The third type is what is called a free-fall airdrop. No parachute is used for that, and it is used for things that are not breakable. For example, to drop leaflets in an area, or the famous candy drops during the Berlin airlift of World War II.

The purpose of this piece is to tell you about my own personal experience with airdrops. In order to do that, I need to take you back to the year 1977. In July of that year, I was planning the biggest climb of my life with friend and climbing partner Brian Rundle. By that time, I had been climbing for 15 years and was ready for something really bold, and, boy oh boy, did we have something bold in mind! Allow me to explain.

A wild, mostly-unexplored group of mountains known as the Lillooet Range was only 50 miles from my home in southwestern British Columbia, or at least the nearest reaches of it were. Access was poor and, as a result, only a few climbers had ever even tried to venture into it. In fact, legendary climber Dick Culbert and 2 of his friends, with their foray into a peak known as Cairn Needle in 1967, were the only ones of record to visit, and their trip only touched the southern edge of the range. Its many peaks had sat un-visited and ignored for a decade since Culbert, and dozens of them stretched north into un-tracked wilderness. The range seemed to be calling me as 1976 became 1977, the long winter days of little climbing allowing me ample time to fantasize about climbing in areas where no one had yet trod.

The project took on a life of its own, getting more grandiose in my mind as spring passed. I didn’t actually meet Brian until May 14th of that year, and we immediately hit it off. In the next 2 months, we climbed Lindeman, Outram, Shuksan, St. Helens, Rainier, Adams and Frosty, in addition to doing a little rock climbing, learning a lot about each other in the process. The Lillooet Range must have been a topic of conversation during those outings, because July found us making serious plans to go there together.

The idea was to have a boat drop us off at the mouth of Stokke Creek on the eastern shore of Harrison Lake. We would then climb up over 7,000 vertical feet and head north, climbing everything in our path, mile after mile. The only problem was that we would run out of food and fuel before long, so how would we re-supply? We could only carry so much, and what we could carry wouldn’t last us much more than a week. There was no chance of re-supplying along the way, either up high or down in any remote valley bottom. Unless ………….. What if we were to drop supplies along the way, up in the high country where our path would already be taking us, maybe on to snowfields, out in the open where we could easily find them again? Hmmmm, it seemed like it might work.

After studying the topographic maps covering our route, we decided on 2 spots which we felt met all of our criteria. Each spot would have to be far enough along the route to do us the most good, but not so far that we couldn’t reach them in time. Each spot would have to be easy to find, foolproof in fact. This was long before GPS existed, so marking the spots on the topo map as carefully as possible once the drops had been made was the best we could do. It was imperative that we’d have to be able to reach those spots with absolute accuracy out in the wilderness, or we’d be in a world of hurt.

On July 20th, I met Brian at his house in Vancouver and we spent the day preparing what would become the 2 free-fall airdrops. I pushed hard for the idea of traveling as lightly as possible, so suggested things like oatmeal, trail mix, powdered soups – nothing glamorous, very spartan – so much so that something as simple as hard candies would turn out to be a luxury item in our provisions. Measuring everything out carefully, we sorted things into daily packages, sealing them carefully. These all went into two large bundles, each weighing 25 pounds, which were double-boxed with padding between the two layers. We waterproofed the boxes with layers of plastic tightly taped around the outside, and finished each one off with long streamers of pink flagging tape, the better to find them later on the glaciers where we’d drop them.

Three days later, on July 23rd, we met at the Pitt Meadows airport. Brian’s friend Terry had agreed to fly us into the wilderness and over the spots where we wanted to make the airdrops. Here’s a picture of the Cessna 172 that we rented that day. Terry didn’t charge us anything for his time, and all Brian and I had to do was cover the $26.00 per hour cost to rent the plane. Twenty-six bucks an hour for a whole airplane – hell, you can barely hire a babysitter for that nowadays!

If you look carefully at the above picture, you can see some boxes sitting on the tarmac beside the plane. What you’re seeing are the two airdrop boxes, each with a pile of pink flagging tape atop them. There were a few other things as well. Brian and I had decided that if the plane should crash while trying this stunt and we survived it, at least we’d have boots, sleeping bags and a few other necessities with us on board to allow us to make the long march back out to civilization.

We took off early on that fine Saturday morning from the small regional airport just east of the Vancouver metropolitan area and headed northeast. We gained altitude quickly and, about 12 miles out, we passed the well-known landmark of the Golden Ears. At 5,598 feet, this peak can be seen by millions who live in the Fraser Valley. On the distant horizon, above the highest part of the peak can be seen the large massif that includes Castle Towers Mountain (8,778′), and a bit farther to the left is the large white peak of Mount Garibaldi (8,787′).

At 33 air miles into our flight, we passed to the northwest of the “Ratney Group”, which consisted of Stonerabbit Peak (6,000′, first climbed in 1975); Mt. Ratney (6,434′, first climbed in 1950); Mt. Bardean (6,300′, first climbed in 1970).

Around the 35-mile mark, we were coming up to Mt. Clarke. This 7,100-foot peak had been first climbed in 1949, and even at the time of our flight in 1977, had only been climbed a few times.

Moments later, we had a better view of Mt. Clarke, here seen more from the northwest.

Things zip by pretty quickly when you’re going 125 miles per hour. The old camera shutter was clicking pretty steadily to try and catch it all. At around 37 miles into our flight, we passed to the west of Peak 6800. In later years, it became known as Nursery Peak, and it didn’t realize its first ascent until April of 1978 by Yours Truly.

Forty miles into our flight, we were coming up on Grainger Peak, elevation 7,207 feet. This beauty was first climbed back in 1942, then sat un-visited for many years. In fact, it never saw its second ascent until May of 1977, only 2 months before our flight. Here’s a view from the west.

Moments later, we had this much better view from the north. Notice Mt. Baker on the distant horizon in the upper left corner, 57 miles away to the south in the USA.

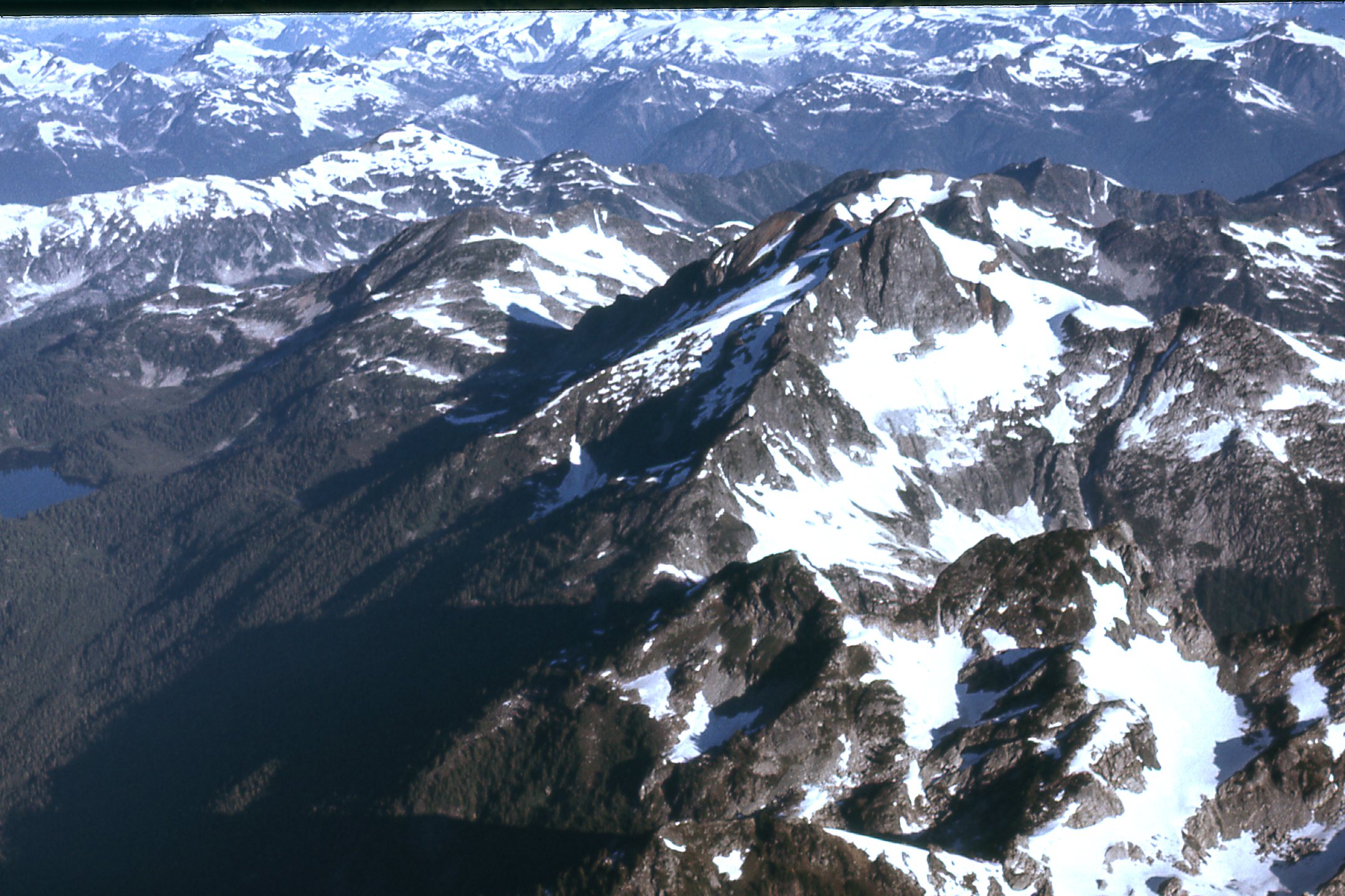

We sped on, continuing to the north-northwest. Flying over Harrison Lake about 5 miles from its northern end, we found ourselves over the Lillooet Range in short order. I was sitting in the back seat of the Cessna by myself, while Brian was up front with the pilot. I had the maps with me, spread out where I could see them and do the navigating. We flew over the valley formed by Stokke Creek, then steered a course more to the northwest.

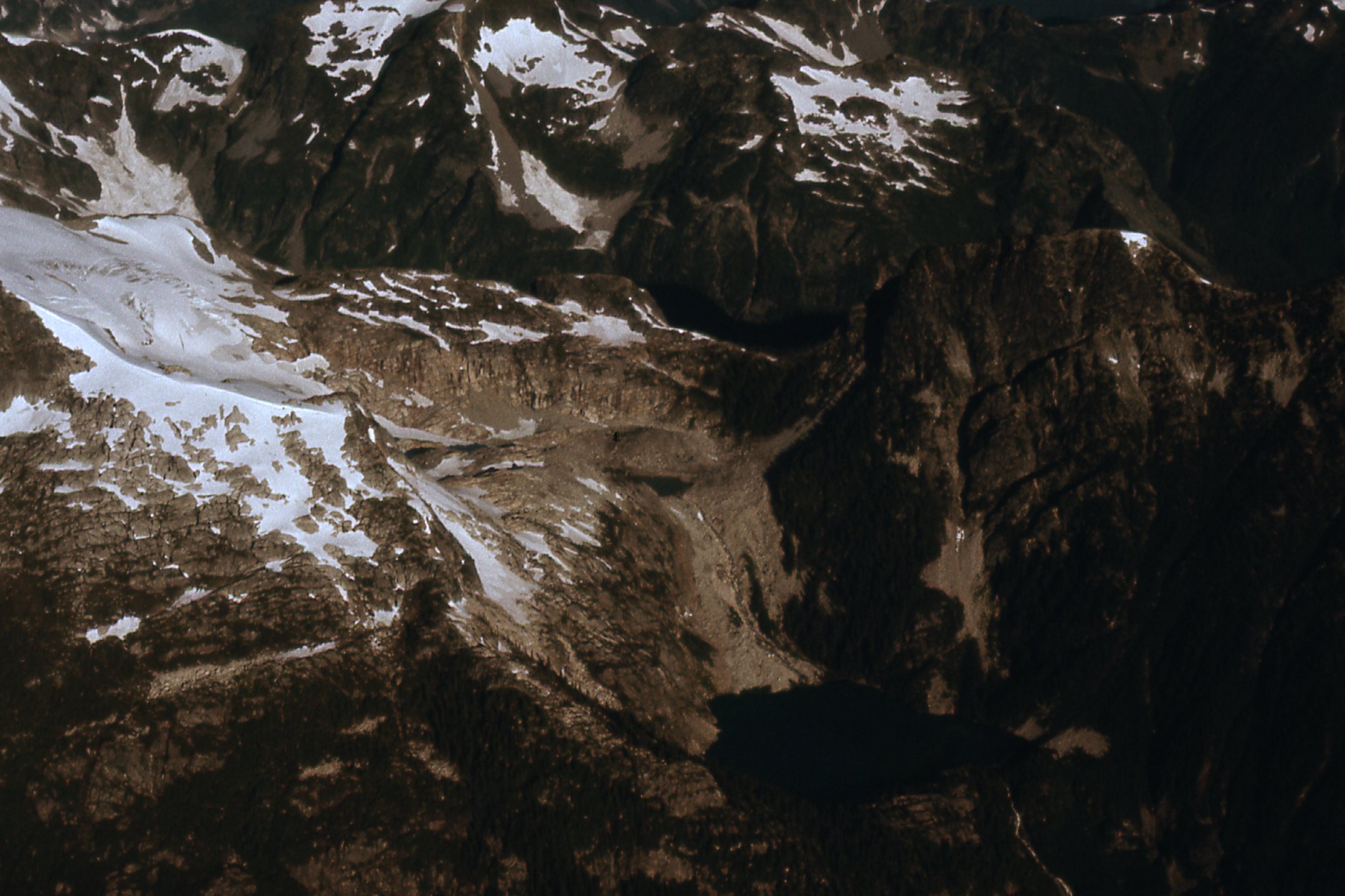

The site of our first airdrop was a broad snowfield situated between Cairn Needle and Mt. Mason, sitting above treeline and at around 6,000 feet elevation – this was about 52 air miles from the airport. Terry didn’t have his mountain flying endorsement, and I think that worried him a bit. He knew we were really counting on him – without these food drops, our little expedition would be a bust. Our plan was to fly as low as possible over the snowfield to make the drop, to minimize the damage to the food boxes. To test how well this all worked, Brian and I had brought along a regular old brick, the type used in construction, and tied long streamers of flagging tape to it, the better to track it as it fell. That was the first thing that went out the window, and we watched it fall. It took several seconds to land on the snow. I’m not sure how much we learned from that test, but now it was time to drop the first box.

Terry dropped as low as he dared and, bombs away, we pushed the box out of the airplane window. He banked so we could watch it fall, and it seemed to drop forever, landing on the snow-covered glacier. Even this late in the season, the snow cover was deep, so the box cratered into it with no apparent damage. Nevertheless, the drop had been made from much too high an elevation for our liking, so we hoped Terry would swoop in lower for the next one.

He turned the plane and flew more miles north, reaching the second drop spot in a matter of minutes. It was amazing that he could cover that distance so quickly, while it’d take us a week or more on foot. The second drop site was like the first, an expansive snowfield above treeline and surrounded by rocky peaks. The second box was a bit too big to fit through the window, so we wrestled the door open. That was a struggle, as the wind resistance was very great at over 125 miles per hour, but we did it. It too seemed to take forever to fall. One mishap, though – I shoved my big face too close to the opening, and as I peered out to watch the box fall, the wind ripped my eyeglasses off my face and they followed the box down. Bummer.

Brian and I were disappointed with the distance the boxes had fallen before hitting the snow. Terry, not having his mountain flying endorsement, was understandably nervous about swooping down low over the snowfield, so he had stayed an overly-cautious distance above it, even though the snowfield was pretty flat. My guess is that we may have been a thousand feet above the snow on each drop. Both drops completed, he turned the plane around and we headed for home.

On the way back, we traced more or less the same route as on the flight in. I did manage a few more photos on the way. I apologize for the quality of these, realizing now that there’s certainly an art to taking good aerial photos, a skill I obviously did not own. I asked the pilot to fly us past a big mountain known as Robertson Peak, elevation 7,400 feet. Here is the view we had on the northeast side, our first approach.

This next one was taken moments later, on the east side of the peak.

And one more, showing the south side.

The date of this flight was July 23rd of 1977. A mere 7 months later, Ross Lillie and I would make an epic 5-day winter ascent of Robertson, not only its first ascent but also its first winter ascent, reaching the summit on February 19th of 1978. This is an ultra-prominence peak, only 34 miles from the airport, and it’s remarkable to think that it was never climbed until 1978. It just goes to show how inaccessible much of that country is. Even though Robertson was a challenging and attractive prize, it sat for another 26 years before seeing its second ascent in 2004. In April of 2021, it saw what would be only its 5th ascent – amazing.

The last photo from our flight was this one, showing the east side of Mt. Judge Howay, elevation 7,376 feet. This peak was first climbed in 1921, but is seldom climbed even today due to its remoteness. Even though it is a mere 24 air miles from the airstrip we used, it is very hard to approach.

By the time we landed at the Pitt Meadows Regional Airport, 2.5 hours had passed. Our total cost for the use of the Cessna was only $65, and we’d had an exciting time of it, to put it mildly.

EPILOGUE

In a day or two, I was able to get new glasses. Three days after the flight, Brian and I were dropped off by boat on the shore of Harrison Lake at the old Stokke Creek landing. We spent the next 8 days climbing our brains out 7,000 feet higher in some of the most spectacular glaciated country you could find anywhere. Every peak we trod was a first ascent. A storm pinned us down for 2 days – we survived it just fine, but those lost days ate into our food supply. Speaking of which, the food we carried with us was nowhere near enough. It was so meager that we both lost a lot of weight in those days of carrying full packs and hard climbing. Sickness didn’t help our situation either. We made the difficult decision to bail before we ever reached that first airdrop, realizing full well that we would run out of food before we ever got there.

As I write this, it has been 44 years since we made those airdrops. Brian and I have both often wondered what became of those boxes of food we pushed out of that Cessna. It’s easy to speculate with no proof, right? Here are some of the thoughts we’ve had, though.

We flew over those snowfields at about 125 miles per hour and perhaps a thousand feet above the surface. Each box would have dropped like a stone once pushed out of the plane. The air speed, combined with gravity pulling on them, would have made each box slam into the snow with terrific force. We thought of everything we could do to pack the boxes so they would survive the impact and remain intact. Once each box had landed, we couldn’t tell how well they had survived the impact, as they were too far away to see clearly.

The 2 main scenarios were that the boxes either remained intact or that they burst open. The snow surface at 6,000 feet on a July morning would probably be fairly hard. However, considering the terrific velocity with which they impacted, they could well have cratered into the snow a bit. Let’s assume for a moment they landed intact and were still sealed in their wrappings of plastic and tape. There was nothing breakable in the boxes. It was mostly dried food, powdered things. We included some luxuries like chocolate and tins of sardines upon which we could feast once we reached the boxes after having traveled overland to reach them. If they had landed intact, it seems likely we would have been able to use it all, or hopefully most of it.

Alternatively, what if the boxes burst open upon impact? The contents sitting out and exposed to the elements would wreak havoc. They would get rained on, snowed on and exposed to the heat of the sun, all the while sitting on the wet surface of the snow. Even if we had reached the first drop, let’s say, 2 weeks after it had been made, and it had been exposed all of that time, much of it could be unusable. If we arrived there and were unable to use much of it, it would be a pretty grim situation. We’d have to make our way out of an even-more-remote part of the range to get back to civilization.

Here’s another thought – what if animals found our airdrops? Mammals have an excellent sense of smell, and ones that could be found on or near such a snowfield include bears, wolves, foxes, wolverines and plenty of smaller ones. If the boxes opened, it’s possible some animals could be attracted from quite a distance and would love to feast on the contents. Also, any number of birds flying over could be attracted by the unusual sight of a box with pink flagging tape tied to it. Ravens or crows could easily tear into a box and get at what was inside.

All in all, it sounds like I’m painting a pretty grim picture of the possible fate of those airdrops, aren’t I? The odds were probably against our finding them intact. We’ll never know. Access is still poor into those remote peaks, and they appear un-visited to this day. It would be interesting to see the reaction of any climbers who, years after our making the drops, happened upon the remnants.