Way back in the 1960s, I lived in Vancouver, British Columbia. I was a student at the University of British Columbia, and I lived in a men’s dorm on campus for 5 years. It was situated at the westernmost tip of the city, and from my dorm room I had a clear view north up a part of the Pacific Ocean known as Howe Sound. Surrounding the sound were a number of beautiful mountains, but the biggest of them all was slightly hidden from view behind other closer peaks. It wasn’t until I finally rode my BSA motorcycle up Highway 99, known in later years as the Sea-to-Sky Highway, that I caught my first glimpse of Mount Garibaldi.

The name had always intrigued me. I knew Garibaldi had been a famous Italian guy, but not much else, so I started digging. The big mountain at the head of Howe Sound had been seen in 1792 by the British explorer Captain George Vancouver, the first European to do so. In 1860, while carrying out a survey of Howe Sound on board the Royal Navy survey ship HMS Plumper, Captain George Henry Richards was impressed by a gigantic mountain dominating the view to the northeast. Richards and his officers named the mountain after the Italian military and political leader Giuseppe Garibaldi, who that year had succeeded in unifying Italy by patriating Sicily and Naples. Mount Garibaldi would have been an impressive sight when Richards saw it from the Plumper, as it rises almost 9,000 vertical feet from Howe Sound, merely 11 miles distant.

The first ascent of the peak was carried out in 1907 by a group of Vancouver mountaineers. Their early efforts in this area helped lead to the creation of a large wilderness area called Garibaldi Provincial Park in 1927. So, fast-forward 49 years to the summer of 1976. I had pondered climbing Mount Garibaldi for a decade, and now the time was right. Unable to find a partner to climb with me, I decided to go it alone. On July 14th, a Wednesday, I left my in-laws’ home in Vancouver at the wee hour of 4:00 AM. Driving my old beat-up Volkswagon Beetle, I traveled up the coastal highway to the town of Squamish, then drove dirt roads east and up to a spot where I could go no farther. My idea was to go in to climb Mount Garibaldi, then head out a completely different way, ending up many miles farther north than my starting point. I wasn’t sure how I’d get back to my car, but I was young (28 at the time) and didn’t care about such details – all that mattered was climbing the peak and having fun.

My car was parked at 3,100′ elevation – I had driven from sea level at Squamish up to there in about 11 miles. I wasn’t too worried about people messing with my car, as it was an ugly piece of crap. In only two years of using it for climbing, I had put 50,000 hard miles on it, and in the process turned it from a nice customized Beetle with a sweet paint job into a Frankencar. I banged it up so badly on rough roads that I carried a large pair of tin snips at all times. Whenever I’d bash the fenders against rocks, I’d snip off another piece of jagged metal, so as not to shred the tires. But I’ve gotta tell you, with that engine over the rear wheels, I could drive places that my friend with his 4×4 was hard-pressed to reach.

I was carrying a full pack, complete with sleeping bag, bivi bag, ice axe and crampons. No tent. It took me four hours to travel just over seven miles to reach the old Diamond Head Chalet at around 4,800′ by Elfin Lakes. Imagine my surprise on the way in to see so much snow everywhere – I could tell by the tree wells that there was ten feet of snow by the cabin! I didn’t have skis or snowshoes with me, but fortunately the snow was quite consolidated, so I didn’t sink in too far with mountaineering boots. The chalet had been built over a period of years by the Brandvold family and completed in 1947. They ran it year-round, catering to hikers, mountaineers and cross-country skiers. In 1971, BC Parks bought it from them, then abruptly stopped maintaining it. It sat closed from 1973 onwards and fell into disrepair.

When I arrived on that mid-July day, it was hard to believe how much snow still lay on the ground. So, here I was – having reached the cabin was a first milestone. Not knowing anything about the place, I shouted out as I approached, and, lo and behold, I heard a reply. The door opened and out came Hans, who identified himself as an assistant warden with Garibaldi Park – he seemed just as surprised to see me. We hit it off immediately, and when I told him that I was going to climb Garibaldi, he asked if he could accompany me. Well, I was delighted to have some company. He told me that he had some time off owed to him by the Man, and there’d be no problem in his coming with me. He threw a few things into a pack and away we went. I was both surprised and delighted that I’d have some company for this pretty serious climb, and wouldn’t have to go it alone. Here is a picture of what I saw when I arrived at the old chalet, which now was being used more or less as a public shelter, 3 years after the BC government had given up on the place. Even though it was mid-July, there was still an honest-to-God ten feet of snow on the ground. The building in the foreground has snow up past the roof line.

From the chalet, the summit of Mount Garibaldi is almost due north, but it is hidden from view by a southern outlier known as Atwell Peak. This is what you see if you look towards it from the chalet – Atwell is the high peak in the upper right of the photo.

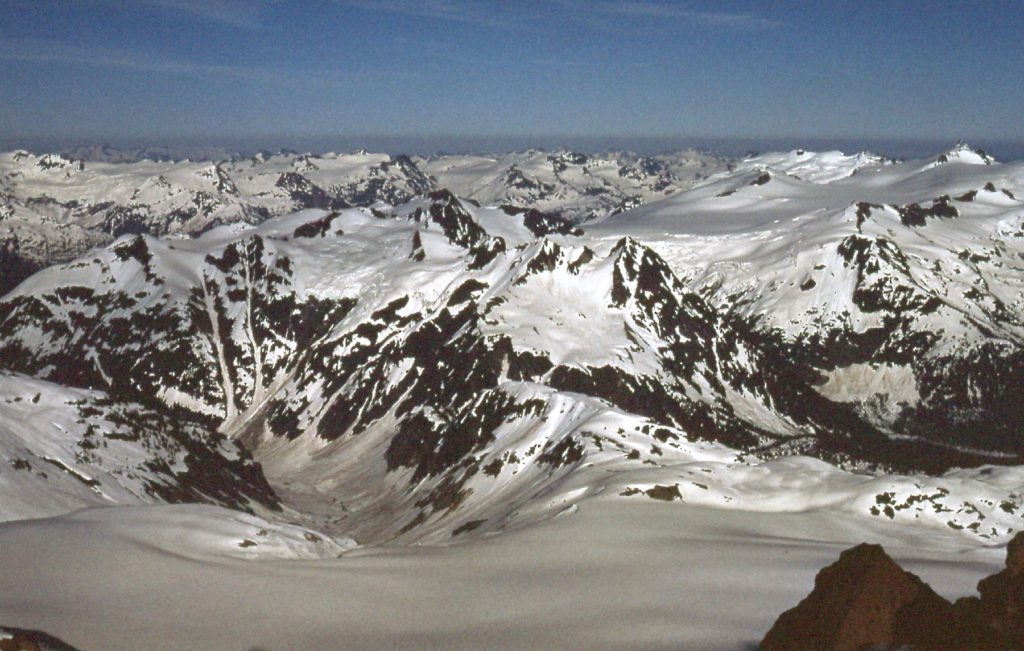

We set out heading north-northwest and gained about a thousand vertical feet over easy country to reach a saddle between Columnar Peak and the Gargoyles. This was a view we had looking northwest over Brohm Ridge to the Tantalus Range in the distance.

We were also getting a closer look at Atwell Peak.

We continued north, down then up again, to reach another saddle. From there, we ascended a broad ridge north to about 6,100 feet, then contoured north-northeast to another ridge. From there, we found a way down its northeast side to the Diamond Glacier. Once on the glacier, we headed north, gaining elevation as we crossed it. From around 6,900 feet, we had this look back south to Howe Sound.

Here’s a good view we had looking across the east cirque of Atwell Peak.

We had to cross the cirque seen in the above photo to gain the ridge in the upper right. That put us on the east ridge of Atwell Peak at around 7,300 feet. Here’s what it looked like on the ridge.

Once we’d crossed the ridge, we were out on the east face of Atwell Peak. Here’s a look at what we saw.

Lower down the slope, it looked like this.

This next photo was taken from about the same spot as the previous two, but looking ahead rather than back. It was taken from about 7,100 feet. The summit is the light-colored rock almost covered in snow right in the middle of the skyline.

Climbing Mount Garibaldi is fairly difficult – it is steep, and composed mostly of very loose, rotten volcanic rock. That can make things more difficult late in the season. Many of you might think that mid-July is pretty late, but in this part of the world, not so much. The mountain was still deep in snow, and that worked to our advantage.

We had no rope, so we needed to be really careful to avoid crevasses – a fall into one could easily have proven fatal. There was nothing to do now but keep climbing – the route lay plainly ahead of us. It took quite a while to climb up to the ridge between the high point and Atwell Peak, an outlier almost a mile to the south of the main summit, but we weren’t in a hurry. Once we gained the ridge, it didn’t take long to make our way over to the summit glacier between Mount Garibaldi and Dalton Dome, Garibaldi’s west peak. With only 200 feet left to go, a couloir led us to the north-west ridge and the summit at 8,787 feet elevation. Luckily for us, the weather and snow conditions were perfect. These next pictures were taken shortly before we reached the summit.

From the broad saddle between Garibaldi and Atwell, here is a shot looking south to Atwell. Our route, hidden from view, had taken us up the steep snow slope to the left of the corniced edge seen in the lower center of the photo.

This next shot, taken from the same spot, shows Dalton Dome, also with an elevation of about 8,600 feet. It sits about a thousand feet to the west-southwest of Garibaldi’s summit.

I love this next shot, which shows Hans heading north on the final stretch to the summit of Mount Garibaldi, elevation 8,787 feet.

We found a ledge and then a couloir which took us to the northwest ridge and then to the summit. Our climb from the chalet had taken us 7 hours. It was our lucky day, as the weather and the snow conditions were perfect. Since the main aim of this piece is to show you photos, let’s get right to it. These next several were all taken from the very summit. The first one is looking southeast towards Pitt Lake, which you can’t actually see in the photo.

In this next photo, if you zoom in, you can see Mount Baker to the southeast, its white summit poking up above the haze just to the right of center of the photo.

In this next one, we are looking east. Notice over on the far right edge of the photo, a white peak a bit higher than the others with a large area of white to the left of it. That’s the Mamquam Icefield and the peak is Mamquam Mountain, elevation 8,515 feet. A surprising number of attempts to climb this peak end in failure. I was lucky enough to summit in early August of 1989, shortly before a 10-day epic on Mount Robson with Brian Rundle and Scott Cranston

In this next one, we’re looking a bit north of east into the McBride Range, seen in the middle distance.

Here’s another look, more to the northeast, to the McBride Range.

This next one is looking to the north-northeast. In the middle distance, about a quarter of the way in from the left, is a dark peak called Castle Towers. More on that later.

This next photo looks to the north. That’s Garibaldi Lake, which sits 4,000 vertical feet below us.

We didn’t stay on the summit but a short while, then decided it was time to leave. We retraced our steps down to the snowfield, then over to the saddle between Garibaldi and Atwell Peak. From there, we dropped down the steep east face on the glacier, then continued down to the névé. We were making good time, and stopped at around 7,200 feet for this look back. If you zoom in, you can follow our footsteps a long way back up the mountain. We crossed the head of the Warren Glacier, passing east of the Sharkfin.

Continuing, we came to the 6,200-foot pass west of Glacier Pikes. It was from near there that I took this next photo. I love how the afternoon sun casts a golden glow on the snow.

Our next task was to descend the slopes of the Sentinel Glacier, which in places were quite steep. This next photo is looking back up where we’d come down it. I took this photo the next morning.

Once off the glacier, we arrived at a hut used by glaciologists which sat on a large, smooth outcrop. It took us until ten o’clock in the evening to arrive there, and we were exhausted. Fortunately, the days are long in July at this latitude. The hut was simple, yet comfortable, with a couple of bunks. I was surprised to see Hans open and devour a can of corn, which he ate cold. He followed it with a can of peas, while I ate some snacks I had brought. I’m not sure if the peas and corn was all the food he had on hand back at the chalet, or he was just in too much of a hurry to grab anything else. In any case, we soon turned in and slept well indeed.

The next morning, we lazed about and didn’t leave the hut until nine o’clock. Here’s a photo of Hans.

He took this one of me. I can’t believe how skinny I was! Ah, those were the glory days.

From the hut, we had this view north down Garibaldi Lake. That striking peak in the distance on the right is the aptly-named Black Tusk, a well-known landmark and popular climb.

In the above photo, we thrashed our way along the left-hand shore of what I believe is called Sentinel Bay. That’s Mount Price poking out into the lake on the left side, and when we reached it, Hans said he wanted to climb it. I was more concerned about how I’d get back to my car, so wasn’t interested in climbing to the summit with him. We did climb together quite a ways up the east shoulder together, though. While I was still higher up with him, I took these 2 pictures.

This next shot is pretty cool. In it, the black flat-topped mountain is called The Table. Look over on its right side, where it slopes steeply down. Do you see that white vertical sliver half-way down? That’s called the Keyhole, and it’s actually an opening right through that ridge. Above the Keyhole, in the distance on the horizon, we see the steep white summit of Mount Garibaldi. The gentle bump over to the right of Garibaldi is Dalton Dome, seen in the summit pictures of yesterday.

We said our good-byes, and I dropped down again to the lake shore, continuing my thrash along its edge. Before long I saw two girls in a rowboat out on the lake. They were pretty close to the shore, close enough that when I called out to them, they heard me. They rowed over to me, and when I asked them if I could get a ride with them, they agreed. Maybe they took pity on me when I told them of my overland adventure. We took turns rowing, and as we went, I took this picture of the mountain I mentioned yesterday. It’s the one a bit to the right of center. It’s called Castle Towers. On March 12th of 1978, one year and eight months later, in the dead of winter, three of us (Brian Rundle, Ross Lillie and myself) would go in and do an epic first winter ascent of it for the record books.

Before long, the girls dropped me off at a trail-head. I was grateful for their help in having avoided a bunch of bushwhacking. Part-way down the trail, I came upon Barrier Lake – at around 4,500 feet elevation, it was still mostly frozen. It’s called Barrier Lake because of its proximity to a geological feature called The Barrier, which is a lava dam that impounds the Garibaldi system of 3 lakes.

Looking over Barrier Lake. We are looking west, and through the gap in the trees we can see a bit of the Tantalus Range.

The Barrier is a thousand feet thick and a mile and a half long, and is quite the imposing sight.

Six miles on the trail brought me to the parking lot, and two more miles of walking down the road (which really sucked because I’d hoped I could catch a ride) finally ended me up at Highway 99. I stuck out my thumb and, before I knew it, a young Japanese tourist picked me up. Here was my plan – I’d gain his sympathy with the story of my adventure, then see if I could convince him to drive me the eight miles of dirt road from the pavement back up to my waiting car. He seemed okay with that. However, the road was somewhat rougher than I might have first led him to believe. He persisted, none too happily, and drove me all the way to my car, then hightailed it out of there before I had a chance to ask him for any more favors. As predicted, nobody had messed with the old beater, and I threw my pack into it and took off. I made it all the way back home by 10:15 that evening. A whole lot of fun crammed into a 42-hour period, and definitely one of my more memorable early adventures. The only reminder of the trip was a world-class sunburn.