Please be sure to read the previous installment of this story, “The Cheam Range – Part 1” before continuing here.

By early July of 1976, I had climbed both Cheam Peak and Welch Peak, the lowest and the highest peaks of the Cheam Range, and the two most popular peaks in the range. I had been bitten by the Cheam bug and was determined to climb the other 6. I didn’t waste any time in returning, and only 18 days later I found myself heading back in. This time my goal would be two of the peaks more in the middle of the range, which necessitated a different line of approach.

Planning these climbs was a lot of fun and also took a lot of time. It forced me to buy a paper copy of the map and study it carefully. This was long before we could look at maps online and study air photos or satellite photos online. I could buy the map at the office of the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) in downtown Vancouver or order it through the mail. The maps were woefully out-of-date when it came to roads or trails, so it often meant asking other climbers for information or calling the BC Forest Service or even calling logging companies. In 1974, Dick Culbert’s book “Alpine Guide to Southwestern British Columbia” had been published and it provided a wealth of information as well.

It was a Friday, the 23rd of July, and after work was done I headed once again to the Chilliwack River Valley and headed up the well-traveled road. Several miles in, I left it and headed north on the lesser road up Chipmunk Creek in my old VW Beetle. I was surprised that I made it all the way up to 3,850 feet elevation. My goal on this trip was to climb both Lady Peak and Knight Peak.

I had this view of Cheam Peak from around where I started – it was the first one I’d climbed in the range.

Counting on decent weather, I didn’t bring a tent, planning to do an open bivi instead. It was around 3:30 PM when I set out with a full pack. The going was pretty good, and I found myself all the way up to 5,800 feet two hours later. I was in a good spot to camp on the snow, so I decided to call it a day. Then I got to thinking about how it was still so early and how I had a lot of daylight left. Why not keep going for the summit? So I did. Here’s a view I had of the south ridge of Lady Peak – gnarly stuff. I avoided this by staying on the easy west slope.

The climb was straightforward by the west slope, and 7:30 PM found me on the summit of Lady Peak at 7,100 feet. This was almost 200 feet higher than nearby Cheam Peak.

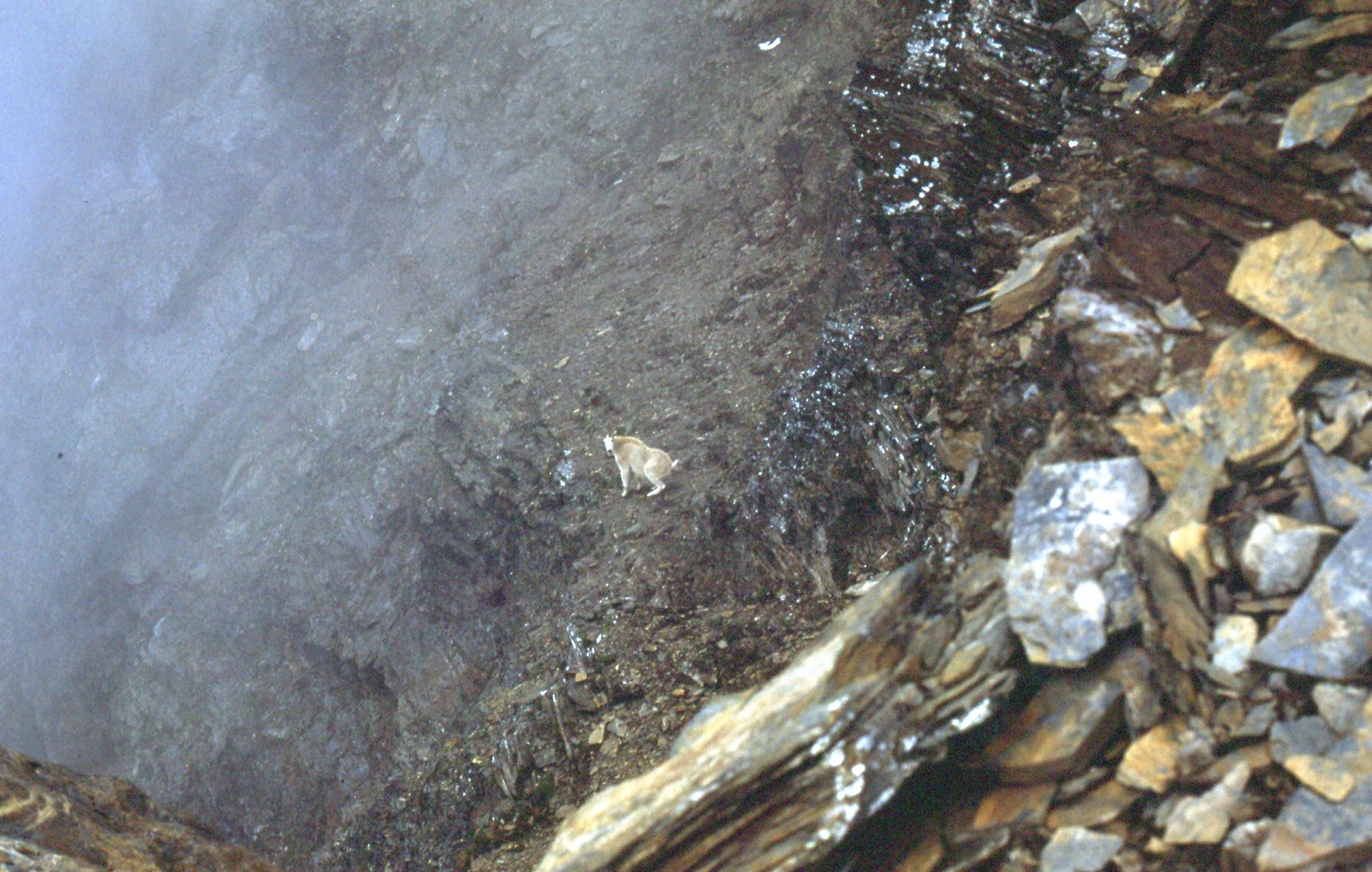

Here is what I saw when I looked down the north slope of Lady Peak.

Views from the summit weren’t too shabby. Here’s one looking south, with Mt. Baker over on the far right.

I like this next one a lot, as it showed my next peak to advantage.

Looking south from the summit. The pyramidal dark peak on the left is Stewart Peak; the farther pointed one just to the right of center in the back is Welch Peak; Knight Peak, to be done tomorrow, is the near one with the long level top which takes up most of the right side of the photo.

I also had this view down to the col between Lady Peak, the one I was on, and Knight Peak, the one I’d try tomorrow. It also shows the north ridge of Knight Peak.

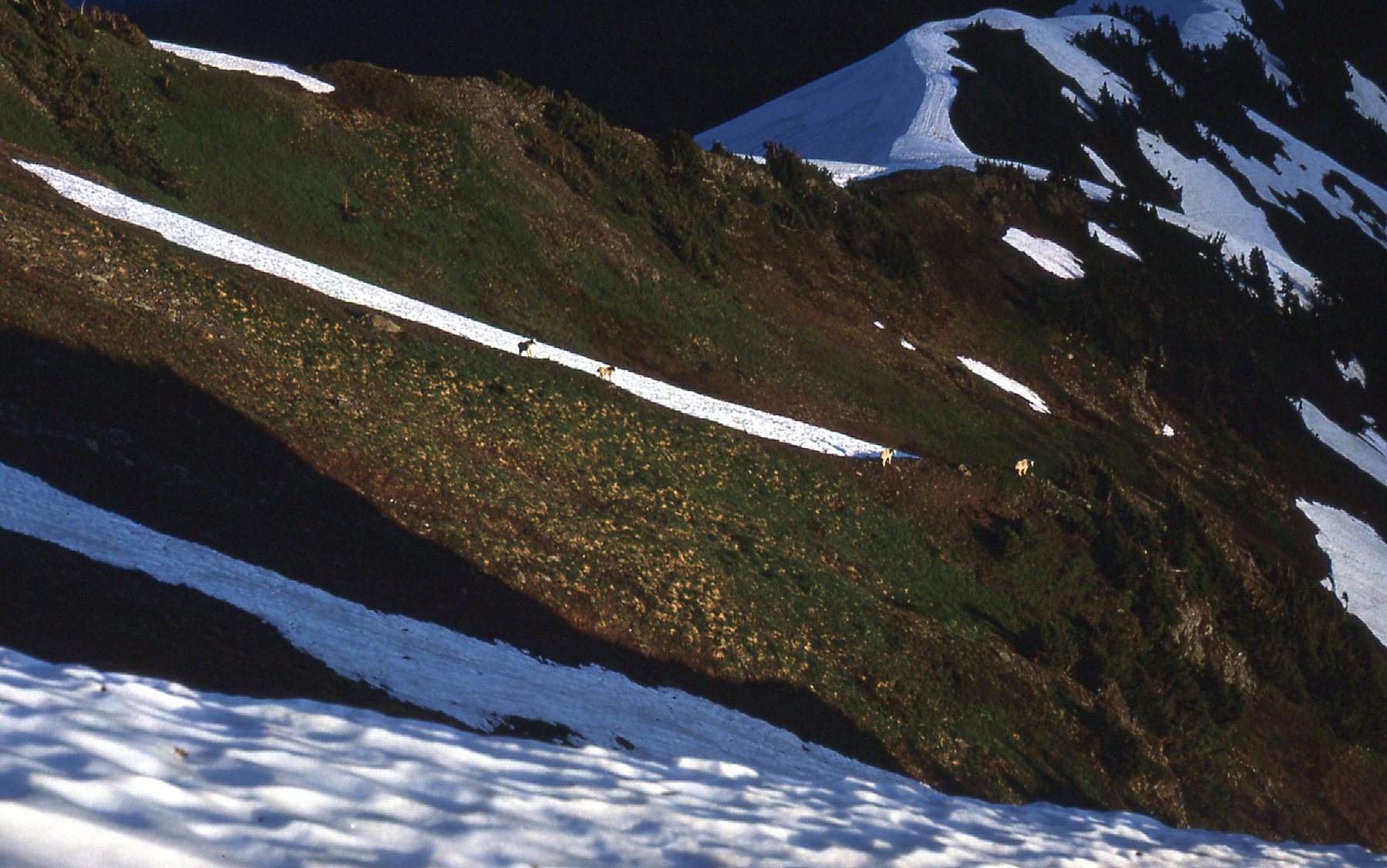

On the way back down to my camp, I saw these 4 mountain goats.

It was an uneventful night spent on the south shoulder of Lady, and early the next morning I headed over to the large basin to the west of Knight Peak and had an easy stroll to the top of it at 7,340 feet. Knight is the easiest climb in the range, but it is also the least visited. Is that because it’s the easiest, or because of access? Here’s a photo I took of the west side as clouds moved in.

This next one shows part of the summit ridge.

As I approached it, I had this good view of the cairn on the summit.

From the summit, I had a good look at this mountain goat. I also saw several others nearby.

There was this misty look down to Wahleach Lake.

The previous evening while atop Lady Peak, I had this view down to the glacier below the east face of Knight Peak.

After a short stay on top, I headed back down, through the basin and back to my camp. Heather was my favorite mountain flower and I got up close to this patch while on Knight Peak.

All went well, and I made it back to my car by 2:15 PM. Four of the peaks in the Cheam Range were now done, and I had spent 3 nights out in order to do them. What would be next?

Little more than 5 months passed, and it was now the New Year of 1977. A couple of my local climber friends from Mission agreed with me that it was time for some winter fun. What could we do? Well, how about an attempt on a few more of the Cheam Range peaks? Heading out on January 5th would mean that anything we did would certainly qualify as winter climbs. Well, that’s exactly what we did – headed out of town by 8:30 in the morning. By 10:15, we had made it all the way to the lower end of Foley Creek. It was a bright, sunny, blue-sky day. We started off on foot okay, but things went to hell in a hand-basket after that. It seemed like we spent the whole day thrashing our way through the snow-filled bush on the southeast side of Mt. Laughington. On the way in, we had some glimpses into the high country.

Finally, we set up camp at 3,300 feet elevation by Airplane Creek, nowhere near as high as we’d hoped to be. We were three – me, Paul and Lota.

Paul Berntsen on the left, and Lota. Check out the knicker socks and knickers. We wore them on every climb, winter or summer. And the suspenders are a nice touch too.

From camp, we could see up to Baby Munday.

We knew we’d need to get an early start, so by 5:30 the next morning we set out from camp. By headlamp, of course. We weren’t using snowshoes, so it was pretty arduous a climb through the bush – it seemed endless. Finally, we reached a small frozen lake at around 6,400 feet and well above the trees. Dang, it was already 10:15 by the time we got there! It had taken almost 5 hours to climb 3,100 vertical feet.

The lake is an interesting spot. From it, 3 of the peaks in the center of the range are easily accessible – Baby Munday Peak, Stewart Peak and The Still. We had come here with big plans, to climb all 3, but we had already burned up so much daylight that it was highly unlikely that that was going to happen. The first one we decided to do was Stewart Peak, as it was the easiest. We could see the top of it from the lake.

I wanted to show you these views of Baby Munday Peak, though, as we climbed up to Stewart. We are looking at the dramatic south ridge.

From high on Stewart Peak, we had this even better view of the summit of Baby Munday Peak. If I were to climb all of the peaks in the Cheam Range, Baby Munday would have to be done sooner or later. It looked daunting.

Once atop Stewart, elevation 7,300 feet, good views rewarded us. Here’s looking down to Wahleach (Jones) Lake, mostly frozen. It’s north of us.

Here, we are looking west to Knight Peak and Lady Peak.

Here’s a look at some other peaks in the range, farther south.

And here’s a look over to The Still, the one we’d try next.

From the top of Stewart Peak, we headed south and reached the saddle between Stewart and The Still. That put us at 6,600 feet. From there, we had more great views.

We could see both Welch Peak and The Still. Welch is the pointed one on the left, while The Still takes up all the rest of the photo in the middle and right.

We had a good view north to Harrison Lake, fully 6,600 vertical feet below us.

Here’s Paul and Lota in the saddle.

From the saddle, we contoured over to The Still and found ourselves on its west side. We made directly up that slope to the summit, and it was steep in places. Here’s Lota leading up the final pitch.

When we took those final steps on to the summit of The Still, elevation 7,500 feet, this is the view we had, a real stunner. It is one of my favorite mountain photos ever. We are looking at the west face of Welch Peak, only half a mile away.

Another picture I took from the same spot shows Foley Peak. It’s the dark pyramid in the back on the right side, in behind the shoulder of Welch Peak. Way out on the distant horizon in the middle of the shot we can see Silvertip Mountain all in white – it’s 20 miles away.

We enjoyed a short stay on top of The Still, then descended directly down to the lake at 6,400 feet. I took one final picture that day, from the lake. I want to point out something to you. If you click on the picture, you can zoom in quite a bit. You can distinctly see our tracks heading up from the lower left corner. They kind of disappear in that scattering of rocks higher up, but they re-appear above, below the dark rock on the summit ridge. They can then be followed, angling up and to the right. They are too faint to be seen ascending the final steep bit past that shadow coming in from the right, and straight up to the summit which is the white expanse all in sun above the shadow.

There just wasn’t enough time to try Baby Munday Peak, so we descended quickly all the way back down to our camp. After packing up, we could see that we were out of daylight. We managed to get ourselves on to the Airplane Creek trail, but as I recall we must have been out of power for our headlamps. It took hours to follow the trail down in the dark with no help from the moon. The guys obviously had better night vision than I, because it was a very frustrating time for me, trying to follow them. I often called out to them to slow down or even stop so I could catch up to them. The ground was frozen and icy, which compounded the problem. Eventually we reached the car at the bottom of the trail and we were back in Mission by 10:00 PM.

Our trip had been successful, with 2 of our 3 objectives climbed. Baby Munday Peak would have to wait. Years later, Bruce Fairley published his excellent book, “A Guide to Climbing and Hiking in Southwestern British Columbia”. Bruce had really done his homework for this one, consulting with many climbers and doing exhaustive research of the mountaineering literature. His chapter on the Cheam Range is detailed and informative. He wasn’t aware of this trip, though, so there are a couple of corrections that can now be made.

He states that the FWA (First Winter Ascent) was done on Stewart Peak in February 1982. I can now state for the record that it was in fact done by the 3 of us on January 6th of 1977. He goes on to state that the FWA of The Still was done in 1977. Well, Paul, Lota and I saw no trace of anyone having recently preceded us in the first few days of the New Year, and since it is highly likely that the party of Dixon, Redekop and Snutch were there later in the winter, it is extremely likely that our ascent of The Still on January 6th was in fact the FWA.

Please stay tuned for the next installment of this story, Part 3.