In early 1990, I had traveled to South America to try to climb Cerro Aconcagua. I had failed in a rather spectacular manner to reach the summit. I acclimated poorly at the base camp on the Ruta Normal, and when I did finally manage to claw my way up to higher camps and eventually adjust to the elevation there, the weather turned ugly and prevented everyone from reaching the summit for an extended period of time. I finally turned tail and headed back to the lowlands, feeling certain that I’d never see that place again. Well, it’s funny how, as time passes, you can replay something over and over in your mind and think about how you should have done it differently. That must be what happened to me as the year progressed. It’s easy to repress all of the worst memories and just focus on the good parts, isn’t it?

During my reminiscing about that faraway mountain, I kept wondering what I could have done differently to have produced a better outcome. Such thoughts weren’t unique to me, that’s for sure. Every climber I know who got a good ass-whuppin’ on some peak and lived to tell about it has gone through similar soul-searching. What if I had done some things differently to acclimatize better to the high elevation? Surely there must be things I could have done better to prepare for a climb like that. Okay, fair enough, but what about the horrible weather? There’s nothing I could have done to change that, right? Hmmm, maybe there was, as unlikely as that might seem.

The summit of Aconcagua lies less than 80 miles from the Pacific Ocean. As such, it’s easy for moisture-laden storms to dump their precipitation on the mountain (it’s always snow because of the high elevation, never rain). Because the summit reaches so high (almost 23,000 feet) into the atmosphere, the winds can be fierce. Airline pilots have recorded wind speeds in excess of 200 miles per hour near the summit. The high elevation is also a recipe for cold temperatures.

So back to the question of what could I have done differently to have produced a better outcome? Well, what about the weather? During my first stay on the mountain, many people told me that January and February climbs were subject to more challenging weather. I don’t know if that is statistically correct, but my personal experience there backed up that theory. They said that December was a lot colder but had more stable (read “less stormy”) weather. So maybe going there in December could make a difference.

How about the fact that I had acclimatized so poorly? Well, what if I took a lot more time and went up very slowly, like all the experts say to do? Surely that couldn’t hurt, and it might make all the difference. In early 1990, I had gone from the lowlands all the way up to the base camp at 14,000 feet in just a few days. It took me ten full days spent there to feel well enough to move higher up the mountain. In retrospect, that seems like an outrageously-long time.

So here’s what I decided to do. I’d head back down to Mendoza in early December and do a whole lot of climbing in another range, going higher and higher over an extended period of time until I felt ready to tackle Aconcagua once again. That way I’d try for the summit a whole month and a half earlier and be in a period of more stable weather. How could I lose, right?

On December 3, 1990 I flew to Mendoza via Asunción and Buenos Aires. Mendoza sits at 2,500 feet, about the same as my home town of Tucson. It was good to see friends I had made on my first trip less than a year earlier. Two days after arriving, I was invited to go on a 4-day climb into a nearby mountain range with a group of young people (I was older than most of their parents). We stayed in a hut and used it as a base. I managed to stagger up a 16,000-foot peak but felt like crap. It was just too high too quickly. I don’t know how those young kids did it, climbing even higher than I did and making it look easy. They weren’t any better acclimated than I, as we all lived at the same elevation. On the way back to town, we had to stop so I could vomit at the side of the road. Once back in Mendoza, I realized that getting prepared for Aconcagua was going to be a lengthy process.

Three days later, my friend Rodolfo Molesini picked me up and drove me to a nearby mountain range and dropped me off at a ski resort that was closed for the season. December is of course the height of the austral summer. He had made a few calls to friends so I could use it as a base. The only people there were a couple of caretakers who kindly let me stay in a dormitory building full of empty bunks. It was perfect – no pressure, no time constraints. The resort sat at about 10,000 feet elevation.

I started with baby steps, the first day doing an easy stroll up a 12,500-foot peak. The next day I did a string of 5 small peaks between 11,500′ and 13,600′. After a rest day, the next thing I tackled was one at 14,600′. So far, so good – no ill effects. Next, I’d try something a bit higher. With bivi gear, I climbed up to a site at 15,100 feet and spent the night.

The next day, I climbed 2 gentle summits at 16,700′ and 17,300′. It was a long day, and by the time I returned to my bivi site to descend back to the ski resort, I was feeling a bit nauseous. That quickly passed, though, and I felt right as rain. That 2-day outing had me climbing 8,000 vertical feet. I was pushing myself a bit hard, but I felt it was paying off with some good acclimation. It was already the 18th of December.

My plan was now to climb to the highest areas of the range. A group of Argentine army soldiers was spending the night at the resort and themselves heading up into the high country the next morning. Their lieutenant took me aside and said that if I wanted, I could ride on one of their mules and they’d put my gear on another mule as they went up into the mountains. How could I refuse! The next morning, the mule train plodded out and in 4 hours had climbed all the way up to about 14,000 feet where they dropped me off. From there, I carried my heavy pack up to a good campsite at around 15,200 feet where I pitched my tent. I felt good, no headache or nausea. Soldiers were moving up and down the mountain. They told me that I wouldn’t need my double boots, crampons or ice axe higher up, so I sent that gear down with them to be left with their lieutenant at the ski resort, saving me 12 pounds of weight.

Early the next morning, I set out with just a day pack. It took me just over 6 hours to reach the summit of an 18,866-foot peak, the highest actual summit I’d ever reached. The weather was co-operating beautifully. I’d been out for 10 hours by the time I returned to my tent.

I spent a good night and was feeling no ill effects. Early the next morning, I slowly broke camp and with a full pack made my way up to a saddle with a few small tent sites. I think it was around 16,700′, and because the wind was blowing so hard it took me a while to set up my tent. Hours later, another group that had spent the previous night camped near me staggered in. They all felt really rough, with bad headaches and vomiting. They had come up from the city too quickly. I had a relaxing rest of my day, ate a good meal and drank a lot.

I was moving at 4:00 AM the next morning, wearing every piece of clothing I had. It was very cold and windy, but clear. It took me more than 8 hours to finally reach my summit at well over 20,000 feet. It was a new high point for me and I was elated. The views were amazing. On the way up, I had this view of the sun rising on Aconcagua.

I could also see Volcán Tupungato, only 25 miles away and standing 21,555 feet above sea level.

I stayed a while on top, then started down. By the time I reached my tent, I had been gone almost 12 hours. Aside from a good headache in the morning, I felt fine with no ill effects on this day, the highest I’d ever climbed. I spent another night there at 16,700 feet. The next day, I made it all the way back down to the ski resort. I packed up all of my gear, and a nice family up for the day gave me a ride all the way back to Mendoza. It was now the 23rd of December.

It is thought that acclimatization gained by climbing and staying up high can last for a few weeks, even if you go to a lower elevation. That’s what I was counting on. Three days later, on December 26th, I was at the trailhead for Aconcagua. After a late start, I had a leisurely day walking to a spot known as Confluencia where I camped for the night. Ten hours of walking the next day put me at the base camp, Plaza de Mulas, at 14,000 feet. I felt great. After one night there, I carried a huge pack up to Plaza Canada at 16,000 feet where I spent a restful night. The next morning, I continued on up to Nido de Cóndores at 17,625 feet. I felt really good, no nausea or headache. I was making really good time carrying my huge pack from one camp up to the next. After one night at Nido, I carried on up to Berlin camp at 19,520. The mountain was dry and snow-free, completely different than when I was there last February. I moved a bit higher than Berlin to get away from a bunch of other climbers. There were snow flurries during the day – I hoped it wasn’t a sign of things to come. I melted enough snow to make 4 liters of water, then turned in, planning an early start for the summit the next morning.

At 3:30 AM, it was cloudy, windy and snowing – much the same at 5:00, 8:00 and 9:00. I was really disappointed, fearing that the weather had turned on me and would ruin my summit chances. There was no way I could start in those conditions, so I spent much of the day lazing in my sleeping bag. A whole day shot. I prayed for better weather tomorrow.

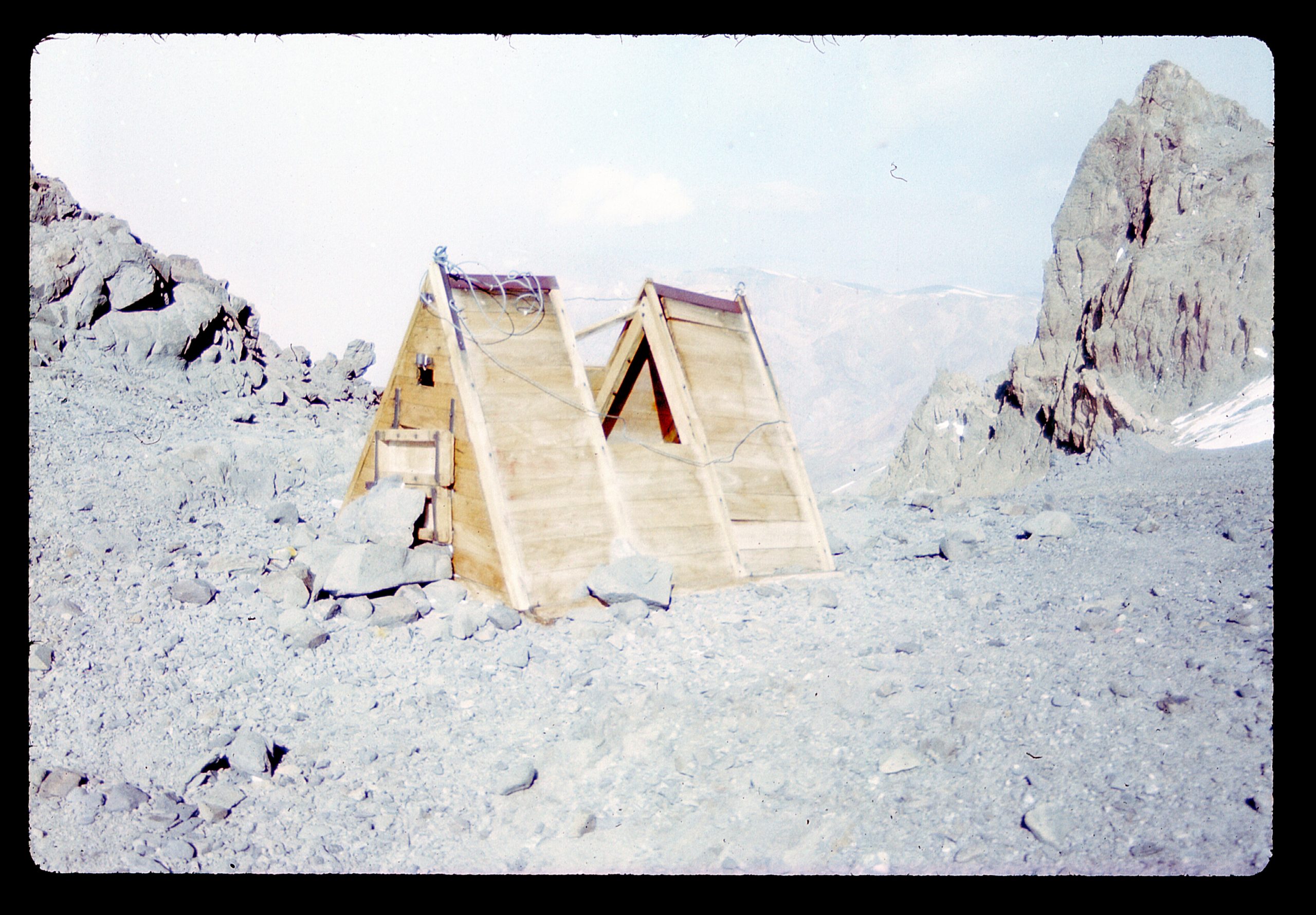

It was New Year’s Day, 1991. I awoke at 3:30 AM. The weather looked a bit iffy. I got ready anyway. I knew that it was now or never. At 4:15 I stepped out of the tent into the light of a full moon and the bitter cold. No pack for me today – everything I needed was inside pockets of the many layers of clothing I wore. It was very windy as I slowly climbed above my campsite. The sun finally rose, giving a false sense of warmth. I crested a ridge and there was the Independencia hut, the highest structure on Planet Earth. It sat at 21,477 feet above sea level. The roof was broken and it was useless, filled with ice.

Up a small rise, and there was the trail crossing the top of the Gran Acarreo ahead. The winds were almost unbelievable. I stopped in the lee of a huge rock and realized my left foot was really cold, that I couldn’t feel my toes even though I was wearing double boots. I almost turned back, but started stamping my feet to get some circulation going, and it worked. Feeling returned, and I continued over to the base of the Canaleta. There I stood, at 22,000 feet, staring up at the crux of the climb. It was the last 800 vertical feet before the summit, and a place that defeated many climbers. It was just a long dirt slope with rocks sitting on it. It was pretty loose, so when you took 2 steps up you slid back down 1. Frustrating if you’re already exhausted, many just give up and turn around at that point.

I must have gone into some kind of time warp, because I spent a full 8 hours climbing up the Canaleta. I felt okay, no headache or anything, but to this day I don’t know where the time went. At 3:15 PM I walked on to the summit at 22,835 feet. Finally, I was there, as were 2 Germans – we hugged each other and took pictures. My quest was over – okay, I still had to get down, but I felt that that would go well, as long as I didn’t make any mistakes. Here’s me on the summit, beside the famous metal cross (mostly hidden to the left of me). Behind me, you can see the west ridge, and the top of the 10,000-foot South Face.

I spent a glorious half-hour on top before I left. It took me 3 hours to get back down to my tent. On the way, I met 2 Japanese climbers at the Independencia hut. One was lying on his back, glassy-eyed and incoherent. It looked like cerebral edema to me. I offered to help to get him down the mountain, but his partner refused, saying the rest of their party would come down soon and they would all get him down. When I reached my tent, I crawled into my sleeping bag and slept for 12 hours straight. Happy New Year!

The next morning, I packed up everything in the fierce cold and wind – it seemed to take forever. In only 2 1/2 hours, I made it all the way back down to Plaza de Mulas, a descent of 5,500 feet. One more night there, then the next morning I left. I covered the 26 miles in 10 hours and was back out to the highway at Puente del Inca in the dark. What a difference all that prior acclimatization had made! I also felt that doing the climb earlier in the season had been important, giving me a window of better weather. The entire trip, pavement to summit and back to pavement, had only taken 8 nights, a far cry from my failed attempt a year earlier. I couldn’t have been happier, and to celebrate spent the next 6 weeks traveling much of Argentina and Chile.

I had one more opportunity to climb high. Six years later, Brian Rundle and I flew down to Bolivia. The airport for La Paz sits at 13,125 feet, one of the world’s highest. We only spent one night in the city before heading out to the Altiplano for our climbing in the western part of the country. The land there is very high. The man who we contracted to move our gear into the mountains for us lived at 13,800 feet. That’s plenty high enough to cause altitude problems for a lot of people. The spot we used for a base camp was at 15,370 feet. We managed a climb of Cerro Chucarero (elevation 17,081 feet) before heading back down and moving into Chile.

Lago Chungará sits just inside the Chilean border at an elevation of 14,820 feet. We stayed in a traveler’s hostel beside the lake for 2 nights, enjoying the camaraderie of other foreigners. On our third day there, we got a ride to our starting point for another climb – we were dropped off at 14,750 feet.

The day was spent carrying big packs across endless dusty slopes of cinders, slowly gaining elevation, until, very tired, we finally called a halt at 16,960 feet. We leveled a tent-site on the rocky slope. We both had headaches, so we took aspirin. And for good measure, some antacids against possible nausea.

It had only been 7 days since our flight landed in La Paz. All of that time had been spent up pretty high, with no gradual ascent anywhere in order to acclimatize properly. This camp was in a good spot, as the climb went straight up the mountainside from there. I made some tea and prepared a freeze-dried meal, but Brian didn’t partake – he was feeling nauseous. We turned in early and slept well. Our plan was to arise at 3:00 AM and be climbing by 4:00.

The alarm woke us right on time. Brian said he wasn’t feeling well and he decided to stay in camp. His decision caught me off guard, as I had never thought about doing this climb alone. Finally, I decided I’d try it anyway, and I left the tent at 4:10 AM. It was bitterly cold, with not a cloud in sight. I climbed by moonlight for an hour or so, lost in my thoughts on the steep, frozen snow. Crampons, ice axe, no pack at all – everything was in my pockets, what we used to call an anorak climb. After a while the moon set, and as I took a break catching my breath, I heard a noise below in the dark. I called out, and Brian answered. I waited for him to reach me. He said that, in spite of his nausea and headache, he “didn’t want me up there alone”. Wow, that was the mark of a true friend and I was very moved by his gesture. That’s why, even today, I would place my life in his hands on any mountain. I knew how he felt – mountain sickness feels like death warmed over, and he was putting out 110% effort to be making the climb with me.

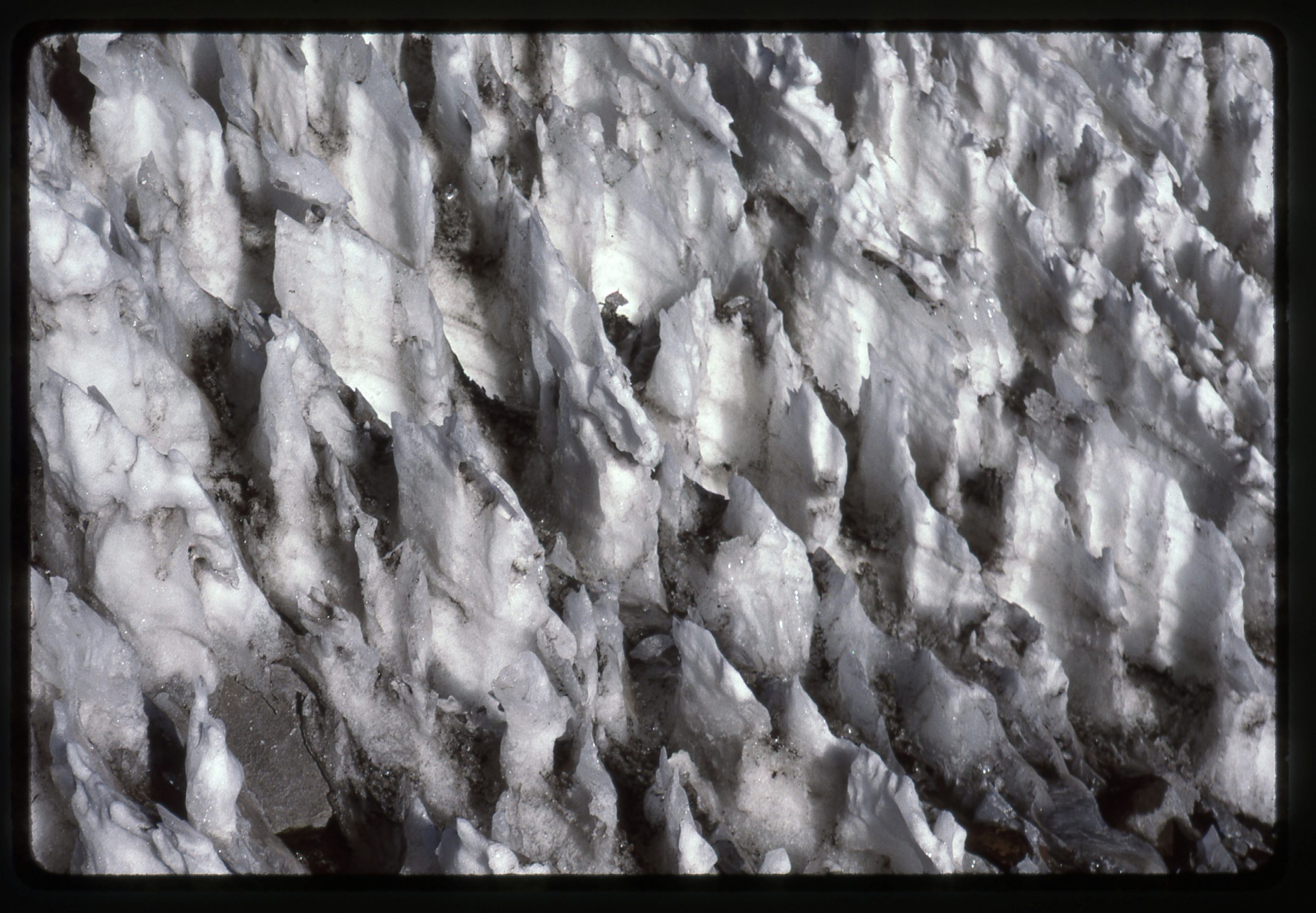

We made slow progress, gaining only 1,200 vertical feet in 4 hours. That brought us to a huge area of nieves penitentes at just over 18,000 feet. These form when snow doesn’t melt but rather evaporates through the process of ablation. These were about 2 feet tall but can be much taller. As you can imagine, because they are sharp and jagged and made of ice, they can be quite an obstacle.

The hours passed as we slowly climbed. We agreed that 4:00 PM would be our absolute turn-around time, that even if we hadn’t reached the summit we’d start back down by then. At 2:30 PM, we reached the crater lip of our peak, Parinacota volcano. Our elevation was 20,762 feet. The crater was 1,000 feet across, and we could see that we weren’t at the highest point. Some distance farther around the lip to the northwest sat the very highest bit, at 20,808 feet.

The temperature was 0 degrees F. and the wind was howling. We both knew right away that we’d cut our losses and start back down.

We made pretty good time on the descent, but it still took us longer than we’d expected. Round-trip, our day was 14 hours. If we had waited until 4:00 PM until we’d started down, we would have been be-nighted high up on unknown ground. This was before we had GPS, so it would have been hard to find our tent on that huge slope in the dark. Brian was sick a couple of times on the way down. He told me to go ahead and reach the tent, which I did just as the sun set. At 18 degrees latitude, there isn’t much twilight, so it was already dark when Brian arrived in camp 20 minutes later.

I fixed a freeze-dried meal, but Brian chose to not eat and instead went straight to bed. I mention all of this to show that mountain sickness can strike anyone at any time. You might be fine on one mountain and sick on the next. It doesn’t seem to matter if you’re a man or a woman, or what age you are. Living full-time up high can make a difference, but most of us live lower down. The next morning, Brian felt much better. We packed up and headed down the mountain, in 2 hours reaching the place we’d been dropped off a few days earlier. A few miles of walking brought us to the highway, then more miles to finally arrive at the hostel by 3:30 PM. The next day saw us all the way back to La Paz, and after 5 days of playing tourist, we were both back home.

That was the last time I climbed up high. Now in my 70s, I look back fondly on the opportunities I had, but I realize I won’t ever see such heights again. It was interesting, to say the least, to experience the good along with the bad, and I’m glad I went through it all.