Friends, this is another of the stories I wrote some time ago, but didn’t have many pictures I could show you. That has all changed, and so I’m presenting the story once again in a revised form and with lots of pictures I took many years ago. I hope you enjoy them.

I’ve had more encounters with Wedge Mountain than just about any other peak ever. I guess it attracted me early on, because it was high, glaciated and pretty easy to get at. At 9,488 feet elevation, it’s the highest peak in the Garibaldi Ranges and also the highest peak in Garibaldi Provincial Park in southwestern British Columbia, Canada. There are plenty of bigger peaks, but it surely does command your attention with a whopping 7,379 feet of prominence. The name comes from its distinctive wedge shape, which is quite obvious from the nearby Whistler Blackcomb ski area. Of course, most of the 2 million skiers who make the pilgrimage to Whistler each year from around the world don’t pay Wedge any mind, instead focusing on the 5,133-foot vertical drop and the 200 different runs, the largest of any ski resort in North America.

The first time I went to try Wedge was in late February of 1968. As you might expect, George and I ended up wallowing in deep snow, and when the third day dawned of our ill-fated climb, we had no choice but to bail.

Our lesson definitely not learned, we decided to go back and try again. This time, we’d go much earlier in the season. October of 1968 arrived, and away we went. Well, the best way I can sum up our second attempt was that it was a complete disaster. We made it up to 5,500 feet elevation, but were once again soundly beaten by the weather. Add to that our inexperience with winter climbing conditions, and the outcome was inevitable. Yes, we had climbed about 2,500 vertical feet, but that was only a small part of what was needed. We still were a thousand feet shy of tree-line.

From Green Lake in the valley bottom, you could ascend the west ridge of Wedge Mountain and stay on it all the way to the top. There’d be no glacier travel, probably some snow, but nothing terribly steep. No cliffs, no rock climbing. The downside would be that there’d be no trail to use, and you’d have to deal with 4,000 vertical feet of bushwhacking.

I went back in late August of 1973, on my way to someplace else, but decided to camp at the base of the west ridge anyway. I was tempted to try the peak again, but decided against it. While there, though, I took this picture from a few miles away. It clearly shows Wedge Mountain in the middle of the photo, and on its left side is the long west ridge.

Okay, so let’s try again. On August 16th of 1974, I went back. My companion and I pitched our tent beside Wedge Creek and right under the power lines at an elevation of 2,300 feet. This left a clean 7,100 vertical feet to climb to reach the summit.

I went to bed early, feeling that it could be a strenuous climb ahead. Up the next morning at the crack of dawn, I started out at 6:00 AM (I would climb alone, as my friend had no interest in mountaineering). This was my fourth visit to Wedge and my third attempt on the peak, and I wasn’t going to take “no” for an answer. I lit out straight into the bush and uphill. As far as bushwhacking goes, it wasn’t bad. In the first hour, I climbed 2,000 vertical feet, propelled by the hordes of blood-thirsty mosquitoes in my wake. I was carrying my new Thommen altimeter, used for the first time only two weeks earlier on Glacier Peak in the Cascades. Finally, for the first time I would make it above tree-line on this peak. I kept up a good pace, the weather was perfect and there’d be nothing to stop me this time. I did get some pretty good pictures, which I’d like to share with you. Here’s one looking back down the ridge from around 7,000 feet. See the very dark bit over on the left middle part of the photo? – that’s the lower part of the ridge where the forest is, which I had to climb up through.

Here’s another one, taken from a bit higher. It shows more clearly the lower part of the ridge which is forested. It also shows the valley and creek which sit to the south of the ridge I was climbing – I think the creek is called Wedge Creek. At the top of the picture, you can see Green Lake. On the far side of it runs the highway, and you can see some of the development associated with the ski resort.

I slowed down after that first hour, but still made pretty good time. Here’s a photo taken as I neared the summit.

At one o’clock I stepped on to the summit. Finally, 6 years after my first feeble attempt, I was there, and it felt pretty darn good. It had taken 7 hours to climb the 7,100 vertical feet, and I was happy with that. I signed in to the register and sat back to enjoy the view as I had some lunch. There was no shortage of amazing scenery to film. Here’s a look back down the ridge from the summit. Notice all the cornices along the edge, making it pretty obvious which was the direction of the prevailing wind. In the distance, the Coast Range stretches to the horizon and beyond.

There’s something important in the above photo to which I need to draw your attention. See the extreme lower right corner, the bit of snow curving up into the picture from right to left? I’m going to show you another photo, one with that same bit of snow, and I’ve put a red dot on the snow for you. See it below?

The red dot marks the very top of an exciting, technical ice climbing route known as the northwest arête. Fifteen years after the time I took this photo, my friend Scott from Toronto came to Wedge Mountain and successfully climbed the mountain by that route. However, instead of descending from the summit by an easier route, he chose to descend by the same route he’d climbed, a much riskier proposition. On his way down, he slipped and fell. He was unable to arrest his fall, and fell over a 300-foot cliff and was killed instantly. Only one month before his death, Scott had spent 10 days on Mount Robson, tent-bound in endless bad weather, with Brian Rundle and myself. When Brian phoned to tell me the bad news, it was hard to accept. Here’s a photo of Scott from that Mount Robson trip.

There’s something else I want to show you from the above photo with the red dot. Go back to it and have a look at the two dark mountains way below, out to the right of the red dot. The one farther to the right with the band of snow coming down vertically from its summit is Parkhurst Mountain, and the other one closer to the red dot is Rethel Mountain. There is a deep valley between them and the ridge I used to climb Wedge, and later in the day on my way back down, I decided (for reasons I no longer recall) to descend back to camp via that valley instead of following the same ridge I used to ascend. A bit of a gamble, as it was all unknown ground, but more on that later.

Check out some of the mountains which I could see from atop my peak. Here’s a view east down Billygoat Creek.

Only 3 miles to the southeast sat Mt. James Turner. It stands 8,868 feet and sits on the southwest side of the Chaos Glacier. It’s the one with the slanted flat part in the upper right corner of the photo.

Then I took this telephoto of the same peak – interesting-looking thing, isn’t it? Those peaks behind it are in the distant Lillooet Range.

Here’s a view to the Spearhead Range.

And here’s one showing the Spearhead Range in front with the Fitzsimmons Range behind it.

Right next door to Wedge Mountain sits another peak, almost as high. It’s called Mount Weart, and at 9,301 feet, it’s no slouch – it’s also the second-highest peak of Garibaldi Park. Here’s the view I had of it from the top of Wedge.

Three years after this climb, I returned with Brian Rundle. We climbed Wedge via its northeast side using the Weart Glacier as our approach. After climbing Wedge, we continued directly over to Weart and climbed it too, for one of the longest and most tiring days ever.

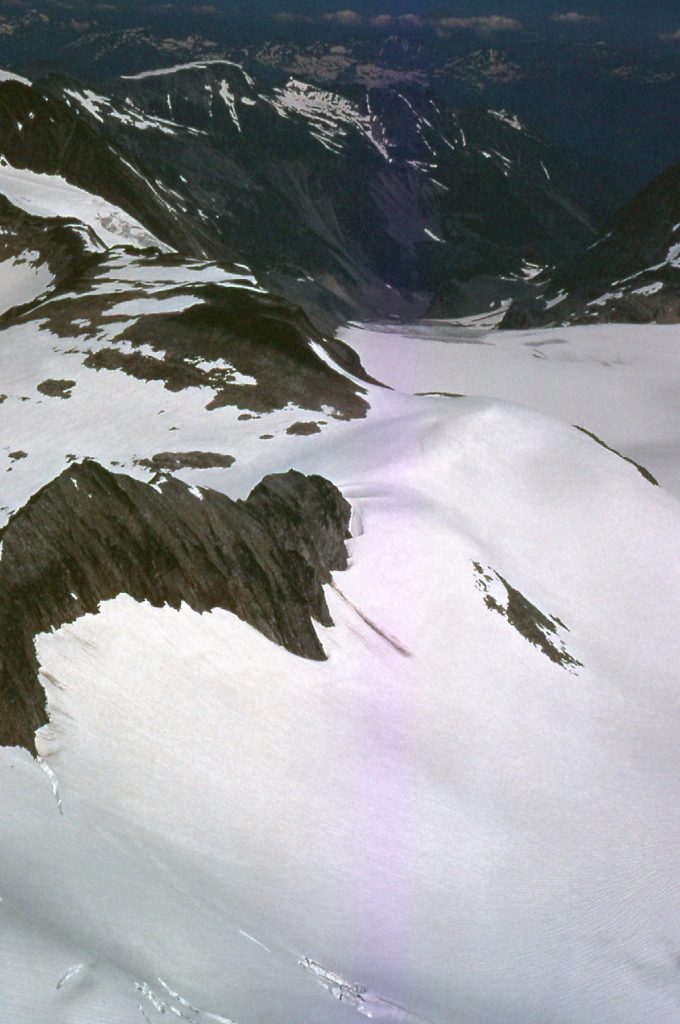

Here’s a look down to the western part of the Weart Icefield.

Here’s another look at the icefield, the main part of it.

And here’s a detail on the Weart Glacier.

There was plenty of ice cloaking these peaks, that’s for sure. Nearby, just to the south, sat Phalanx Peak, looking like this (this was its western end). In later years, much of this mountain would be covered by the ski runs of Blackcomb.

All good things must end, and so did my time on Wedge Mountain. I set off back down the west ridge, my ascent route, but when I had lost 3,000 vertical feet I bailed off the ridge and got myself into the valley to the north. Here’s a look I had back up to the summit area. The top is well back of the pyramidal shape you can see.

My escape route down that valley went well enough, with just one hiccup. When I got all the way back down to the power lines, I got tangled up in a swamp. It took a bit to work my way past that, but I finally walked back into my campsite at 6:00 PM, a full 12 hours after setting out. Everything about the climb had gone perfectly, and I was so happy it had all worked out. As I said earlier, I came back in 1977 to climb it again with Brian, and that was the last time I ever set foot on the peak.