Please be sure to read Part 1 and Part 2 of this story before starting Part 3.

As I was visiting all of these former missile silos, each one armed with a Titan II missile and warhead back in the day, I couldn’t help but wonder about the nuclear weapon mounted atop each of these missiles. How scary were they? Enough to act as a deterrent to the Russians so they’d never think of using their missiles against us? It made sense that their weapons matched those of the U.S., so hopefully both countries realized it would be insane to ever launch their missiles – doing that would result in their mutual destruction. A bit of research showed me what damage our warheads could do.

Each of these missile sites I was visiting had been equipped with a B53 nuclear bomb. That was the largest nuclear weapon in the U.S. arsenal at the time, with a yield of 9 megatons. Here’s a scary thought – the predecessor to this one had been the B41 bomb, with a yield of 25 megatons. God help us all! When I tell you about the B53 bomb and what it could do, it seems insane to even consider the earlier B41.

Assuming a detonation at optimum height, a 9 megaton blast would result in a fireball with an approximate 2.9 to 3.4 mi (4.7 to 5.5 km) diameter. The radiated heat would be sufficient to cause lethal burns to any unprotected person within a 20-mile (32 km) radius (1,250 sq mi or 3,200 sq. km). Blast effects would be sufficient to collapse most residential and industrial structures within a 9 mi (14 km) radius (254 sq mi or 660 sq. km); within 3.65 mi (5.87 km) (42 sq mi or 110 sq. km.) virtually all above-ground structures would be destroyed and blast effects would inflict near 100% fatalities. Within 2.25 mi (3.62 km) a 500 rem (5 Sievert) dose of ionizing radiation would be received by the average person, sufficient to cause a 50% to 90% casualty rate regardless of thermal or blast effects at this distance.

We need to remember that Tucson was ringed by 18 of these missile silos. Assuming that Russia would want to knock out all 18 of these, it’s a safe bet that 18 of their finest missiles, each armed with an equally-deadly nuclear weapon as ours, would come raining down on Tucson’s silos. These missile silos were on all sides of the city. During news conferences held in the 1960s leading up to the construction of these missile bases, it was grudgingly revealed by the military, medical experts and scientists that the chance of anyone in the city surviving was absolutely ZERO. No doubt whatsoever about that. I guess that’s why it was said, back then, that if World War III ever happened, those living in Tucson would be the lucky ones – we wouldn’t suffer, as our annihilation would be immediate and complete. There are a million people who live here today.

The warhead of the B53 used oralloy (highly enriched uranium) instead of plutonium for fission, with a mix of lithium-6 deuteride fuel for fusion. The explosive lens comprised a mixture of RDX and TNT. Here’s a photo of what one of these B53 bombs actually looked like, as it would have sat inside the tip of the rocket. They built 340 of these bombs, but only 54 of them were mounted on Titan II missiles. Each was just over 12 feet long and weighed 8,850 pounds.

These Titan II missiles were designed to be launched from underground missile silos that were hardened against nuclear attack. This was intended to allow for the United States to ride out a nuclear first strike by an enemy and be able to retaliate with a second strike response.

The order given to launch a Titan II was vested exclusively in the US President. Once an order was given to launch, launch codes were sent to the silos from SAC HQ or its backup in California. The signal was an audio transmission of a thirty-five letter code.

The two missile operators would record the code in a notebook. The codes were compared to each other and if they matched, both operators proceeded to a red safe containing the missile launch documents.The safe featured a separate lock for each operator, who unlocked it using a combination known only to him or herself.

The safe contained a number of paper envelopes with two letters on the front. Embedded in the thirty-five letter code sent from HQ was a seven-letter sub-code. The first two letters of the sub-code indicated which envelope to open. Inside was a plastic “cookie”, with the five letters written on it. If the cookie matched the remaining five digits in the sub-code, the launch order was authenticated.

The message also contained a six-letter code that unlocked the missile. This code was entered on a separate system that opened a butterfly valve on one of the oxidizer lines on the missile engines. Once unlocked, the missile was ready to launch. Other portions of the message contained a launch time, which might be immediate or might be any time in the future.

When that time was reached, the two operators inserted keys into their respective control panels and turned them to launch. The keys had to be turned within two seconds of each other, and had to be held for five seconds. The consoles were too far apart for one person to turn them both within the required timing.

Successfully turning the keys would start the missile launch sequence; firstly, the Titan II’s batteries would be charged up completely and the missile would disconnect itself from the missile silo’s power. Then the silo doors would slide open, giving off a “SILO SOFT” alarm inside the control room. The guidance system of the Titan II would then configure itself to take control of the missile and input all guidance data to guide the missile to the mission target. Main engine ignition would occur subsequently for a few seconds, building up thrust. Finally, the supports that held the missile in place inside the silo would be released using pyrotechnic bolts, allowing the missile to lift off.

There were a couple of sites to the west of Tucson, in a very rural area known as Avra Valley. One of them had been turned into a sort of a memorial to the Titan II legacy, and that was the next one I visited.

Missile Site #12 570-3 36 miles at 291 degrees from Davis-Monthan air base

I had a pretty good idea ahead of time what to expect at this one. Miles west of Tucson, along Silverbell Road, a paved road heads southwest towards a working mine. We leave it quickly, though, where we see this sign marking the missile site.

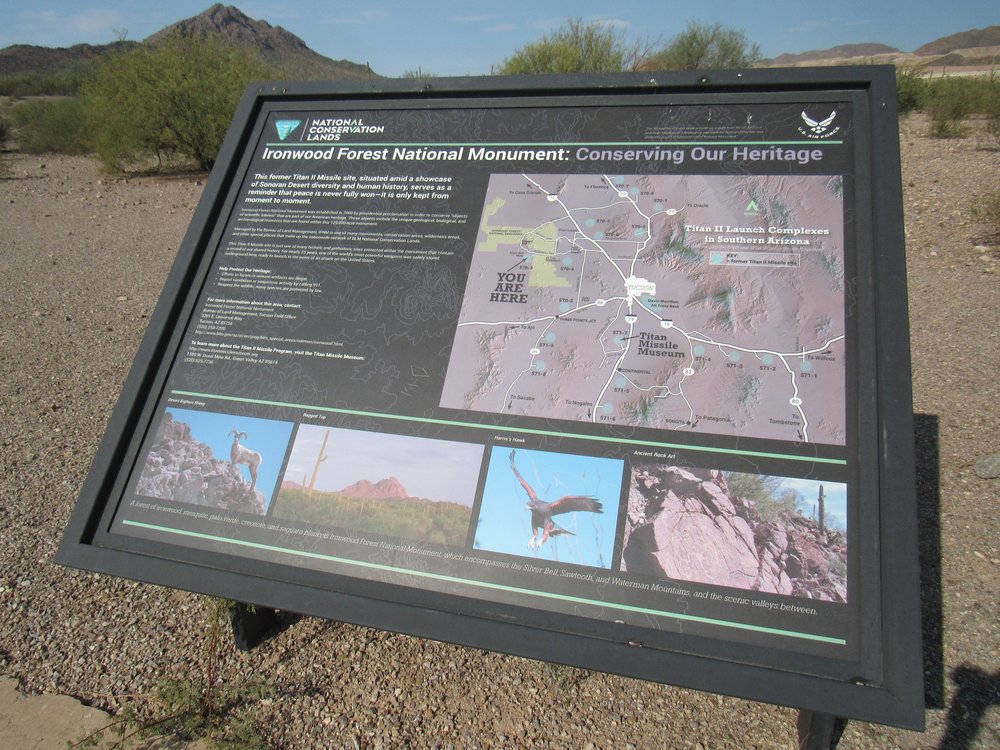

A quarter-mile of following the original paved “driveway” takes us to the site itself. The first sign that greets us there is this one.

There was a small parking area, which even had handicapped spaces. They had done this spot up nicely for tourists like me – for once, I wouldn’t have to be sneaking around on private property, it was all legitimate.

They had made a circular road that went around the site, a level road easily walked, and they had installed a series of informative signs. Here’s the first one I saw.

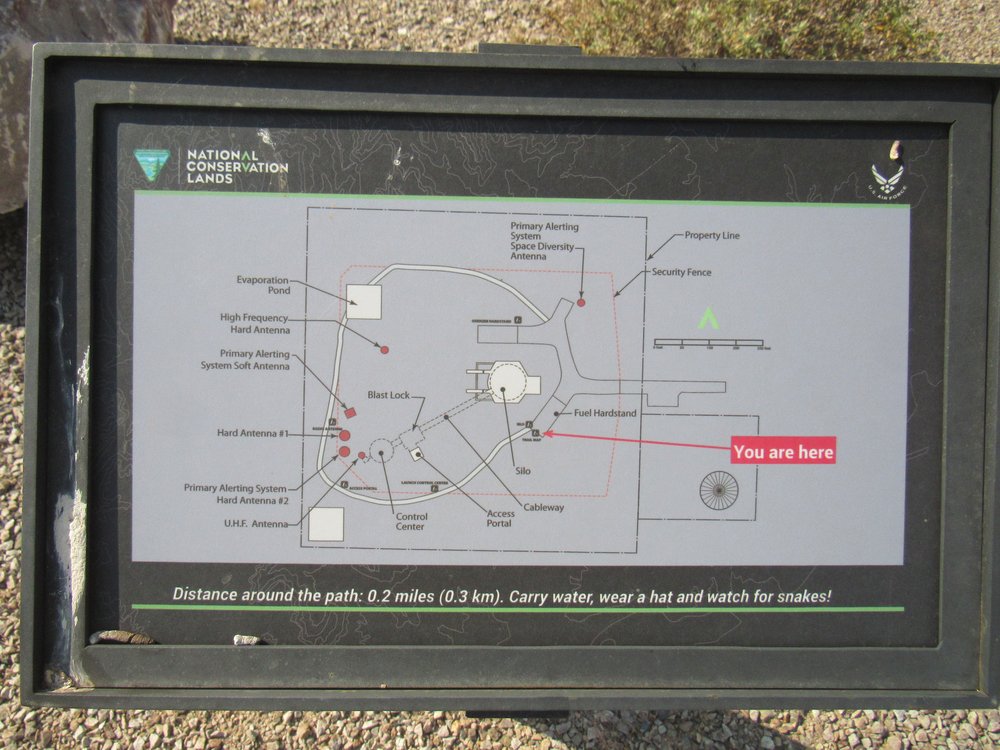

Rather than have me write down all of the text from each sign, why don’t you click on each photo and then you can zoom in as much as you want to see the pictures and the writing. The first sign showed a 3-dimensional view of what had been built here. It looks like it had taken about 2 1/2 years to build the entire missile base.

The second sign showed a timeline of the Cold War, and also a detailed view of what one of the Titan missiles looked like.

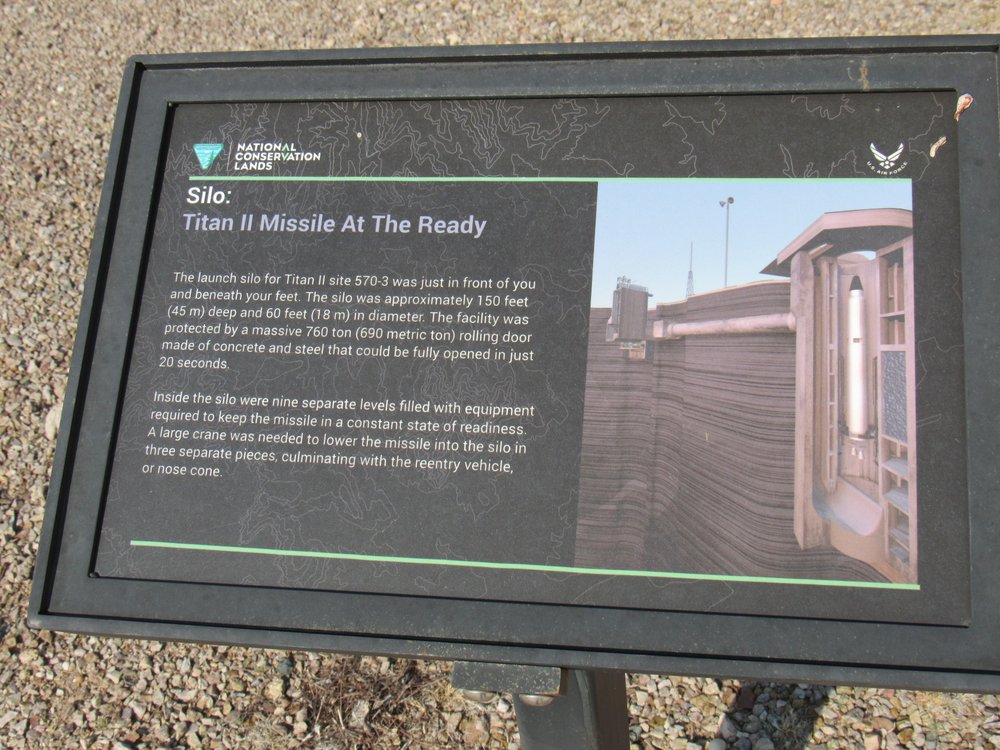

The third sign showed details of the interior of the silo.

The next picture was an informative display on the Ironwood Forest – this missile base sits within that desert preserve.

The next display shows that the silo was 150 feet deep and 60 feet in diameter. It was protected by a massive 760-ton concrete and steel door which could be rolled back in just 20 seconds in order to launch the missile.

The next display was a plan view of the entire base. This told me a lot about how each of them were laid out, and explained some of the things I had been seeing at each one.

I had reached a point in the self-guided walking tour where I got a good view of the nearby Silverbell Mine. It was hard to picture this nuclear missile silo less than a mile from a working mine, one that has been producing copper for 150 years.

The next panel describes the layers of security involved in gaining access to the interior of the silo.

Look at the details in this next photo. It shows where the crew lived and worked, and is quite interesting.

Another panel shows how the missile was loaded with propellant.

I had been seeing these large concrete hardstands at every missile base, and now I knew their purpose.

In Part 1 of this story, I mentioned that there were Titan II missile silos in other states. Arkansas had 18 missiles of its own, and one day there was an accident at one of the silos. It happened like this.

On September 18, 1980 a worker dropped a heavy tool he was using – it fell 80 feet in the silo, bounced and pierced the skin over the first-stage fuel tank. This caused it to leak a cloud of fuel. It was then decided to turn on an exhaust fan to disperse the fuel, but due to arcing in the fan, the fuel exploded. This initial explosion catapulted the 740-ton silo door away from the silo and ejected the second stage and warhead. Once clear of the silo, the second stage exploded. The 9-megaton warhead landed about 100 feet from the base’s entry gate, but fortunately its safety features prevented any loss of radioactive material or nuclear detonation. One man died and 21 others in the vicinity of the blast were injured. The entire launch complex was destroyed. At daybreak, the Air Force retrieved the warhead which was returned to the weapons assembly plant. The launch complex was never repaired – it was filled in and sold to a civilian buyer. The site was eventually listed on the National Register of Historic Places. That wasn’t the only mishap that occurred at a Titan II missile silo – there were at least 3 others I know of.

On August 9th of 1965, a fire and resultant loss of oxygen when a high-pressure hydraulic line was cut with an oxyacetylene torch in Site 373-4 near Searcy, Arkansas killed 53 people, mostly civilian repairmen doing maintenance. The fire occurred while the 750-ton silo lid was closed, which contributed to a reduced oxygen level for the men who survived the initial fire. Two men escaped alive, both with injuries due to the fire and smoke, one by groping in complete darkness for the exit. The missile survived and was undamaged.

On the 23rd of June, 1975, one of two engines failed to ignite on a Titan II launch from Silo 395C at Vandenberg AFB in California. The launch was part of the Anti Ballistic Missile program and was witnessed by an entourage of general officers and congressmen. The Titan suffered severe structural failure with both the hypergolic fuel tank and the oxidizer tank leaking and accumulating in the bottom of the silo. A large number of civilian contractors were evacuated from the Command and Control bunker.

On August 24, 1978 SSgt Robert Thomas was killed at a site outside Rock, Kansas when a missile in its silo leaked propellant. Another airman later died from lung injuries sustained in the spill.

These accidents only go to show that these missiles were dangerous things. Thankfully, built-in safeguards prevented any detonation of the warheads – can you imagine? Here is a picture of the re-entry vehicle which contained the warhead – this would be fitted to the tip of the missile.

Somebody had a good sense of humor when they painted this blast door of a Minuteman missile silo.

Funny but serious at the same time.

Missile Site #13 28 miles at 296 degrees from Davis-Monthan air base.

This next one wasn’t too far from the previous one I discussed, just a few miles closer to Tucson but still out in the area they call Avra Valley. Like many of the 18 sites around Tucson, it is now private property, but none more so than this one. The property actually has a street address – 8540 North Anway Road. When you pull up to the front gate, you’d think you were arriving at Fort Knox. The usual quarter-mile paved road leads into the property.

If you walk up to the first of two gates, you’ll see all of these signs greeting you.

Okay, I googled this, and it’s a real thing. Here’s what it says:

A castle doctrine, also known as a castle law or a defense of habitation law, is a legal doctrine that designates a person’s abode or any legally occupied place (for example, a vehicle or home) as a place in which that person has protections and immunities permitting one, in certain circumstances, to use force (up to and including deadly force) to defend oneself against an intruder, free from legal prosecution for the consequences of the force used.

Check out this mother of all fences, which surrounded the entire property. It was 8 feet high, not counting the razor wire which graced the top of it.

There was a second gate beyond the first, where emus roamed.

I walked around the property on its south side, on Arizona State Trust Land, to see what else I could see. Through his fence, I could see a large concrete slab, one of the hardstands.

There were still plenty of signs along the fence.

And more emus inside the fence. Maybe they were attack emus.

This was the only other bit of missile silo stuff I could see from outside the fence. This may have been the first such thing I’d seen so far at any of the sites.

Anyway, there really wasn’t much to see here – his house was surrounded by a thick belt of trees and quite invisible. I soon left. A few photos exist showing some of the details inside when it was sold to a private buyer.

Inside the launch control center, the man in the moon gazes into the four-member crew sleeping quarters.

The logo for the 570th Strategic Missile Wing survived being buried for at least 15 years on a 6,000-pound blast door

Okay, there’s one more installment of this story to come. Stay tuned for the conclusion, entitled Armageddon – Part 4.