Back during the cold-war era, Tucson, Arizona was in a unique position. The mighty U.S. military machine had decided that the desert around the city was an ideal location to position many ICBMs (Inter-Continental Ballistic Missiles), ready to launch at the enemy should they dare to launch theirs at us. It was said that should World War III ever occur, the inhabitants of Tucson would be the lucky ones. Russian missiles would rain down upon us and obliterate the city, surrounded as it was by all those missile silos, and nobody would suffer – we’d all be wiped out in an instant. Quite the sobering thought. I’d like to tell you about those missiles – what they were and where they were.

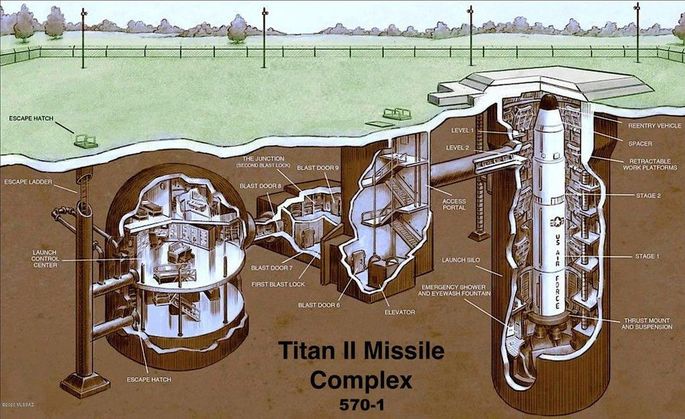

Each of the missile silos around the city contained one LGM-25C Titan II rocket with a nuclear warhead. These were 2-stage rockets and stood 103 feet tall. Fully loaded, they weighed 304,000 pounds. They were designed to launch from underground missile silos hardened against nuclear attack. This was to allow the U.S. to ride out a nuclear first strike by the enemy and be able to retaliate with a second strike response. Here is a link that will tell you everything you’d ever want to know, and more, about these rockets.

I moved to Tucson in 1987 and it was then that I learned that the city had been surrounded by these missiles. The 390th Strategic Missile Wing was located at Davis- Monthan Air Force Base on the southeast side of the city. There were 2 strategic missile squadrons, the 570th and 571st, and each of them was responsible for 9 of the missile silos. Tucson’s missile wing was established in 1962, but had been disbanded in mid-1984, a few years before I moved here. It’s what occurred to establish, man and maintain and finally decommission these silos that’s the fascinating part.

Once the Air Force decided where to put these missile silos, they had to build them. It made sense that if they were to be run out of Davis-Monthan, they’d have to be reasonably close to the city, and they were. The nearest one to the base was north of the city about 20 air miles away, and the farthest was to the east about 43 air miles distant. Oh yes, each of the Missile Wings was responsible for 18 missiles, and besides the wing in Tucson there was also one in McConnell Air Force Base in Kansas and one more in Little Rock Air Force Base in Arkansas.

Many years after moving to Tucson, in fact it was in 2020, I decided I should go and visit each of the sites – as a Tucsonan, it seemed like the right thing to do. I had no idea what I’d find, but at the very least it should prove interesting. The first thing I needed to do was to find the location of the 18 silos, and I was lucky enough to find this site which showed me exactly that. Once on that site, I learned that each silo had its own designation. For example, the one up in the town of Catalina was known as 570-9, meaning it was the ninth one of the sites run by the 570th Strategic Missile Squadron. It made sense that each of the silos would have some sort of a proper designation. The website was great, as I could look at a satellite image of where the silo had been, and if I then converted that to a map view, I could see how to drive there. That was a crucial first step, and I felt encouraged. Now that I knew where each of them was, I could get on with the business of visiting them.

There was a numerical order to these silos, and for the most part they were in clusters, or in strings along highways. The first one, though, was kind of the odd man out. It sat by itself just off of Arizona State Highway 77, exactly 29 miles due north of Davis-Monthan Air Force Base. I’ll give all distances in air miles and by compass direction from D-M.

Missile Site #1 570-1 29 air miles at 000 degrees from D-M

This is the first one that piqued my interest. I saw an ad on-line offering it for sale in early 2020 for the tidy sum of $495,000.00. It even had its own address – 63514 E Highway 77, Oracle, Arizona. The site covered 11.78 acres. I had no idea what to expect when I went there. The first thing that greeted me was a massive locked gate just off the north side of the highway.

There was a paved road that ran from the highway to the missile site – I would soon learn that every silo had its own paved “driveway” that did the same. If you walked the road, you soon came to another gate with more warning signs.

This silo was advertised as being in excellent condition, as shown by these pictures which accompanied the ad.

Here is a diagram of what the whole silo complex looked like.

There was a fence, and in places a block wall, completely surrounding this property. The owner had gone to a lot of trouble and expense to keep people out, because this site was very open and accessible compared to ones I would visit later on.

The Titan II was the largest operational land based nuclear missile ever used by the United States. The missile had one W53 warhead with a yield of 9 Megatons (9,000 kilotons). It’s hard to wrap your head around that fact – an explosive device equal to NINE MILLION TONS OF TNT.

Missile Site #2 571-1 43.3 air miles at 108 degrees from D-M

This one had also been listed for sale early in 2020 – asking price, $495,000.00 for the 15-acre site. When the Air Force decommissioned this one in 1984, they covered it with dirt. The man who then bought it waited until 2016 to go back in with an excavator and dig down 35 feet to access the facility. What he found was untouched, and like a time capsule. Inside, he found: a newspaper from 1984, documentation from commanders to the officers, and a Pepsi. These are pictures he took.

After having examined the site, the owner filled it back in. By that, I mean he pushed the dirt back over the entrances. The inside of the site is still as you see it in the above pictures, but he wanted to re-bury the entrances to protect it from vandals. I can see how it’d be quite the liability if someone broke in and was hurt or died in there. When I went there, it was all flat desert. Aside from a few concrete pads, you’d never know there had ever been anything there. Here is the access road to the site as seen from the highway – the base was about a quarter-mile in.

They had certainly done a good job of covering everything over. A couple of large concrete slabs were still visible.

In one of them was a grilled opening – just a few feet down inside it, it appeared to be blocked, or filled with dirt. On another large slab sat a shipping container, which was empty.

There was another slab – a hole in the middle of it had been filled with concrete.

A few of these curved slabs were visible.

Power came to the edge of the property, and apparently there was also a well.

A large area had been cleared and graded in the past.

Aside from what I’ve shown you here, there wasn’t much else to see – certainly nothing to get you into any kind of trouble. Everything was well-hidden underground. This place is way out in the desert, not close to anything else, but Interstate 10 is only about half a mile to the north. So the previous 2 sites were the ones that had been for sale in the past year. All of the others were a blank slate for me, and I had no idea what I’d find.

Missile Site #3 571-2 33.7 air miles at 116 degrees from D-M

If you take the Whetstone exit off of Interstate 10, about 35 miles east from downtown Tucson, you’ll find yourself at a MacDonald’s restaurant. Something called West Titan Drive heads west from there and ends a mile and three-quarters later right beside the freeway (it used to be a frontage road). Unlike the others I’d visited up until now, this one had no signs saying “keep out” or “private property”. Where the access road into the site began, there was a cattleguard and a tired bit of chain-link fence, but you could easily step around them.

The paved road leading the third of a mile up a gentle hill to the missile site had suffered badly in its 35 years of sitting idle.

Where the road ended, I found the usual concrete slabs.

I also found a friend.

As in the other sites I’d visited, there were places where concrete footings had supported something – perhaps antennae. These had been cut off and were long gone.

This site had been undisturbed. Surrounded as it was by private land, that may have acted as a deterrent to guys like me coming in and poking around. I found not a speck of trash, or any other sign of human visitation for that matter. Certainly everything had been well-covered by the military and was still that way.

Missile Site #4 571-3 26.3 air miles at 122 degrees from D-M

This was another of those sites which was located right by the freeway. Even closer to Tucson, it was out in the desert by itself with no neighbors. It looked like someone might be living on the property when I visited, though. The gate at the entrance had this clever metal sign. I love it – “Thompson Atomic Ranch”. Obviously, this guy knew what he had.

The property had sold for $300,000.00 back in 2006. It was advertised as 16 acres and having 3 commercial wells.

The metal gate was unlocked, the reason being that it gave access to State Land – accessible to anyone with a permit. Look in the next photo – that communications tower in the background is also accessed through this same gate.

I let myself in and drove the quarter-mile to another gate – this is where the private property began. It was pretty cool that this guy even knew the exact designation of his site, seen below on the left side of the gate.

At the other end of the gate was this clever metal sculpture. Thompson must have been the owner, and here he is riding the missile.

Beyond his locked gate, on the property itself, sat a large Quonset hut and a shipping container, as well as a lot of equipment.

Okay, I couldn’t say for sure if anybody was actually living there, but the owner had power to the hut and the place certainly didn’t look abandoned. I had no way of knowing if the underground workings were accessible. There was nobody there to talk to, so I soon moved on. This guy wins the prize for the best art work, though.

Here is an old photo taken inside his site, inside the blast lock room looking toward the launch control center. The blast doors are open.

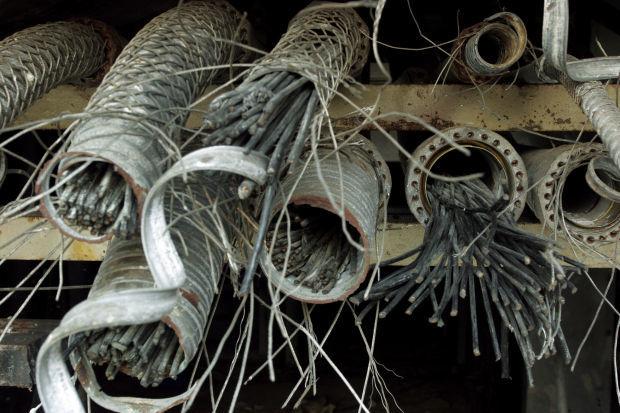

Another old photo shows how the wires were cut when the site was decommissioned.

Missile Site #5 571-4 20.1 air miles at 139 degrees from D-M

The next site I visited caught me somewhat off guard. Rather than the typical bunch of concrete slabs sitting atop the ground, what I found was quite the opposite. Pima County owned this site, and they had excavated much of it for fill dirt. The result was that some of the underground stuff was exposed. Here is some of what I saw. The first thing you come to is a gate, which was not locked.

A small sign sat nearby.

It seems to me that if the county didn’t want you to enter the site, they would have at least locked the gate. This next photo shows the front side of the gate – I’m guessing that the metal rods sticking out were to discourage anyone from trying to push the gate open with a vehicle. It didn’t much matter, though, because a hundred feet away you could simply drive around the end of the fence and down into the site.

As you pass beyond the gate, you soon come to the excavated area. Have a look at this next picture – back in the day, the entire site was filled with dirt level with the top of these concrete structures. Now we can tell what the round concrete slabs seen back in Site #2 were the tops of.

My research showed me that this next structure was the access portal – so much concrete and rebar protecting it!

But here’s the best part of all – this rounded dome was the launch control center. Back when this site was operational, there was 8 feet of dirt over the top of the dome. It is made of metal.

Here’s a close-up.

Visiting this site was a real eye-opener, as it was like seeing things from the inside out. Even so, all the important stuff was still way underground. What I really wanted was to see deep inside one of these missile bases. Would I be lucky enough to do that as I continued my exploration of the remaining 13 sites? Stay tuned to see what happened next.

Stay tuned for the next part of the journey, entitled “Armageddon 2”.