Please be sure to read “Armageddon – Part 1” before continuing here.

My engineer friend Dave Jurasevich brought up an interesting point. Who built all of the 18 missile bases that surrounded Tucson? He suggested that it would probably be only one contractor that did them all. If you think about it, it wouldn’t do to have a whole bunch of different companies building them, for a few reasons. First of all, the Air Force would want all of them built at the same time. The Cold War was raging, and time was of the essence. Once the order was given, they all needed to be built right away, and it would take one huge company with resources enough to do that. We’re talking about the highest level of security imaginable here, so instead of spreading the work out among a bunch of different bidders, it made sense to have it all done by one reputable company (“Loose lips sink ships”).

There was one company big enough for the job. Fluor was chosen by the US Air Force to carry out the work. I’d like to quote from their website an outline of how the work was done:

To expedite startup of the Titan II system, construction and missile site activation were accomplished in phases, beginning with earthwork and the heavy steel and concrete construction of the basic control center, blast lock, cable way and silo structures.

Next, the interior steel support and shock-resistant structures, along with mechanical, electrical, heating and air conditioning were completed, followed by the control systems that interfaced for missile activation. This phase also included the fabrication and installation of the silo closure doors and the checkout and testing of the installed systems.

As the prime construction contractor for these phases, Fluor contended with a construction schedule impacted by a massive number of design changes and by the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Each site consisted of a silo, tunnel and control center deep underground. Fluor oversaw construction of most of the ground support equipment, structural steel and piping at each complex. Each silo was fitted with a seventeen-inch-thick concrete tube, or launch duct. The Titan II was housed inside this steel-clad duct. A five-foot-thick concrete and steel door covered each silo.

Fluor utilized a decentralized project office which was fully responsible for all detail engineering, office and financial functions, purchasing, scheduling, safety, labor relations and construction management. Its project organization essentially paralleled that of the Corps of Engineers to enhance coordination, communications and efficiency in project execution. Fluor implemented a strong safety program that was followed by all trade unions and employers working on site.

Understanding the national security implications of the project, Fluor delivered the 18-site Titan II ICBM complex on schedule to the U.S. government despite abundant change orders and design modifications.

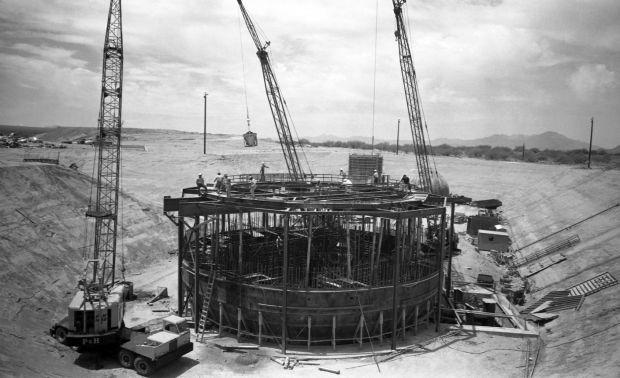

Here are a few photos showing some of the work as it occurred back in the 1960s. This one shows how the first Titan base near Tucson is fortified with concrete in May, 1961, as workmen continuously pour around the clock. Huge buckets of concrete are swung by a crane to the top of the structure where the material is poured into the hole through pipes in a slipform operation.

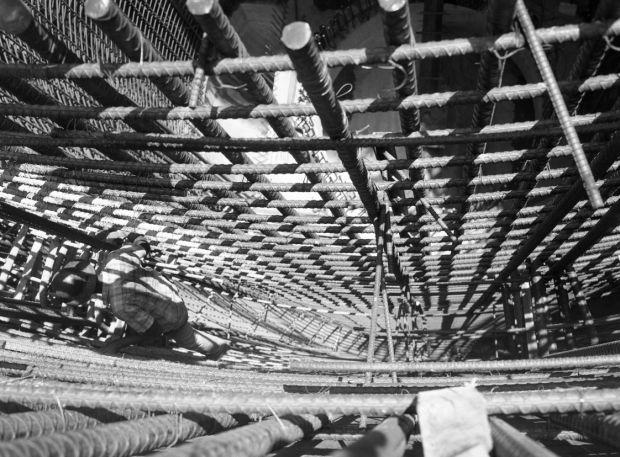

This one shows how thousands of feet of heavy-duty reinforcing bar are tied together to form the backbone for tons of concrete to be poured

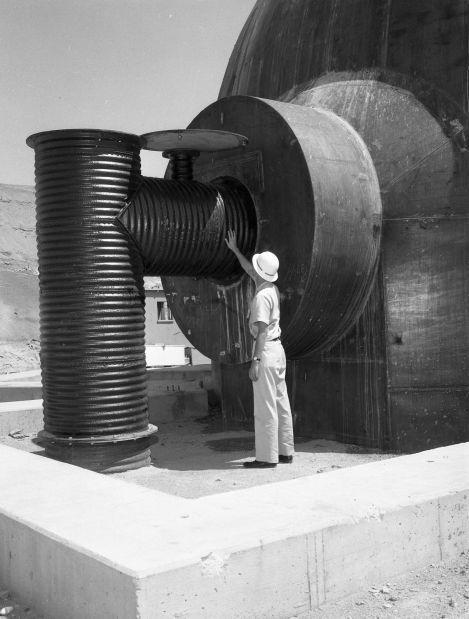

Here, a worker inspects the ventilation tubes extended from the hardened silo.

This next photo shows how workers prepare for the missile. The dome will house the control center. You can see that they’ve already excavated pretty far down, but they had a long way yet to go.

I love this next photo. It shows a section of the missile arriving on a military plane. How the heck did they fit that inside the jet?

The previous photos were all of a more general nature. Now I’d like to continue with my tour of the individual missile bases and show you what I found at each of them.

Missile Site #11 570-2 22.6 miles at 256 degrees from Davis-Monthan Air Base

As you can tell from the compass bearing, this missile had been located west of Tucson. It sat out in empty desert only a quarter-mile from busy Highway 86. There are a number of decommissioned photos I’d like to show you that were taken at the site. This one shows workers in the nearly-completed silo.

Here are photos showing the missile (actually just a part of it) being lowered into the silo.

This missile site sits on Arizona State Land, but it is nowadays just a sorry patch of desert. The entrance road is still good pavement, but with no gate the only warning is that you need a state land permit to enter – here, that is totally ignored by everyone.

Once at the site, only slabs remain.

This next one shows the top rung of a rebar ladder. Otherwise, this hole was filled with concrete.

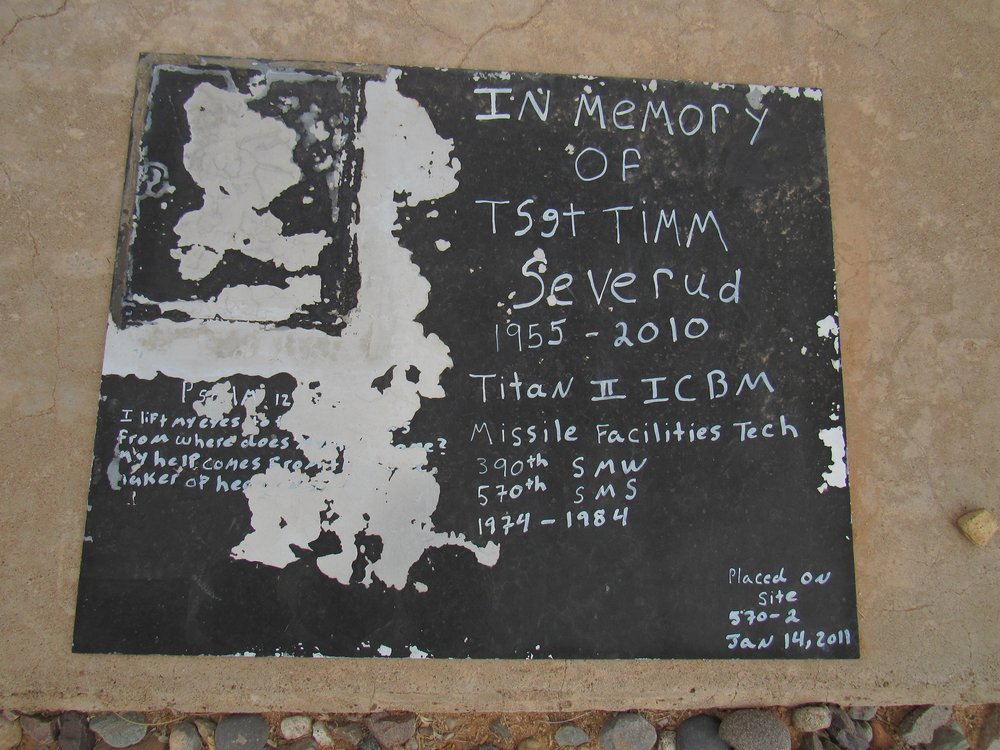

Something on another slab caught my eye – see the black thing?

Here’s a close-up.

There’s a lot of information on the plaque. We know it was placed on Site 570-2 (which is indeed the correct designation of this site) back on January 14th of 2011. It honors the memory of Air Force Technical Sergeant Timm Severud (1955-2010) who died at the young age of 55, and who served at this site from 1974 to 1984. He was part of the 390th Strategic Missile Wing and also a part of the 570th Strategic Missile Squadron. There is also a quote from Psalm 121: “I lift my eyes to the hills. From where does my help come? My help comes from the Lord, Maker of heaven and earth.” I’m guessing there may have been a photo of him in the upper left corner.

This last photo was of what had been some sort of entrance at one time. Spray-painted on its wall were the words “Way To Hell” with an arrow pointing straight down into the bowels of the earth.

There wasn’t really anything else to see here, so I moved on to the next one.

Missile Site #10 571-9 29.9 miles at 246 degrees from D-M

This is another of the bases now owned by Pima County. It sits south of the village of Three Points, along Arizona Highway 286. There is a locked gate, but other nearby roads bypass it and give easy access to the property.

The county had done here what they had done at Site #5 which they also owned. They had removed a massive amount of dirt that filled in the site and covered the facilities – not all of it, mind you, but enough to create quite a hole. The underground facilities were still there and buried. Here is the first impression you get as you walk to the end of the access road and come upon the site. An access hatch sits alone at the edge of things.

Another view inside the pit.

Here’s another remnant.

Chunks of steel and concrete had been pushed to the side.

The most interesting thing about this site was the Border Patrol’s presence. Sitting atop a man-made hill was one of their MSC vehicles.

Just below the white top-most part of the mast is an arm sticking out to the right. It’s a big eyeball, which they can rotate in any direction. Day or night, they can detect any movement for a long distance, whether it be a vehicle or someone on foot. I didn’t go over to it and bother the agent sitting inside, but I did give them a friendly wave when I saw the eye rotate to look at me. This site sits squarely in the middle of the Altar Valley, a popular conduit for undocumented persons and for drugs entering the country from Mexico.

As I left the property, I saw this concrete pillar marking what I think is the northwest corner of the property.

Otherwise, there was probably less to see here than at any of the properties I’d visited so far.

Missile Site #9 571-8 35.5 miles at 235 degrees from D-M

This site was also south of Three Points, like the previous site, but 8 miles closer to Mexico. It sits on private property and is well-marked as such.

The owner even displayed one of the original military signs that used to be at the site.

Although I couldn’t visit the actual site, I could walk across the Arizona state land that surrounded it. That allowed me to get a closer look at what was there. The first thing I saw was a large building, but look what’s in front of it – it’s a hatch, open in a concrete slab. That told me right away that this owner likely still had access to the innards of the silo.

At the end of the 1,500-foot paved road leading from the highway to the property itself, there was a fence that surrounded all, as well as another gate. This one had some good signs too.

This sign puzzled me – why would it be written in English and Arabic?

This sign showed me he had a sense of humor.

Okay, you’ve seen the pictures I took – pretty limited, I know. However, I can also show you some nice decommissioned photos taken back when this property was an active missile base. These were taken in December of 1977. This first one shows the giant concrete sliding dome that covered the silo.

This was taken inside the silo, and shows the actual 9-megaton nuclear warhead mounted on the missile.

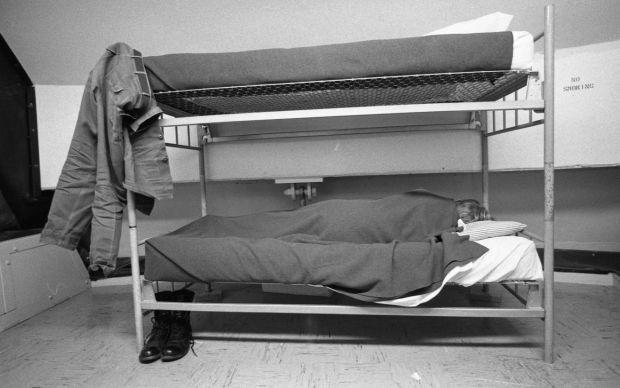

This shows the sleeping quarters inside the base.

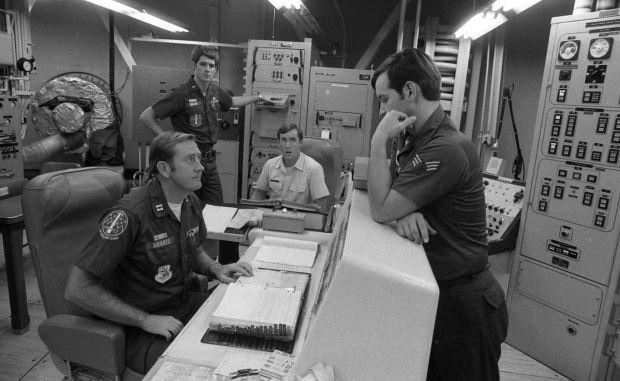

Here are pictures taken during a drill. In this first one, Captain Charles Harris, sitting in front, discusses the situation with his crew.

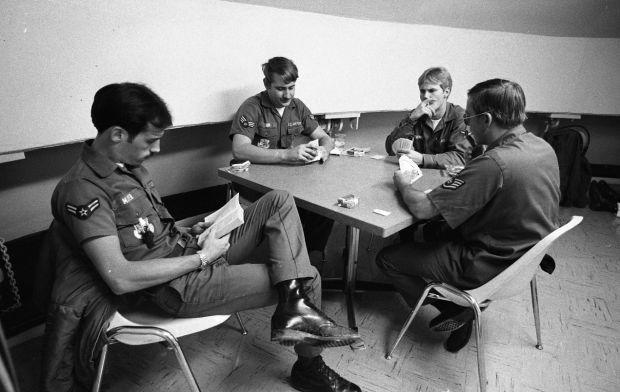

These are on-duty crew members at the ready.

These are off-duty crew members.

Here’s the crew leader with his hand on the launch key.

The previous pictures made the whole missile business seem very real to me.

My journey of exploration was about to continue, so stay tuned for what I’ll find in “Armageddon – Part 3”.