This story has been a long time coming. As I write this now, I have already published a surprising 415 stories on this site. Before I ever started, if you’d have told me that 8 years later I’d have come up with so much material to write about, I might not have believed you. Early on, I wanted to write a story about Glacier Peak, but I wanted more than just my diary notes to go on. I hesitated all those years, but now have what I needed – all of the photos from that trip – so I’m all set. Here goes.

Glacier Peak is a stratavolcano in the Cascade Mountains of Washington State in the USA. Although it is the 4th-highest peak in the state, it is lesser-known than Mount Rainier (14,410 feet), Mount Adams (12,276 feet) and Mount Baker (10,781 feet) because it is set farther back from the main spine of the range and not so visible as the others. Even so, it has a whopping 7,497 feet of prominence. For years, my only glimpse of it was from along a short stretch of Interstate 5 near Everett. It was something of a mystery, which made it all the more tantalizing. It sits only 70 miles from downtown Seattle, yet is far less known than the aforementioned 3 higher peaks which are all more visible and accessible. With the obvious exception of Mount Saint Helens, it is historically the most active volcano in the state with 5 major explosive eruptions in the past 3,000 years.

As I sift through my climbing records, I’m surprised to see that I actually climbed it before I ever climbed Mt. Baker (done on December 3, 1976), Mt. Rainier (done on June 21, 1977) and Mount Adams (done on July 3, 1977). I even climbed it before I climbed Mount Saint Helens (done on July 13, 1977 – yes, Martha, that was before it blew up). That was quite the climbing jag, the last 3 done in less than a month’s time and all in the company of long-time climbing partner and friend Brian Rundle).

Glacier Peak sits squarely in the middle of the Glacier Peak Wilderness Area, which in turn sits in the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest. The mountain is surrounded by a veritable sea of ice in the form of 11 named glaciers, as follows: Sitkum Glacier; Scimitar Glacier; Kennedy Glacier; Ptarmigan Glacier; Milk Lake Glacier; Vista Glacier; Ermine Glacier; Dusty Glacier; North Guardian Glacier; Chocolate Glacier; Cool Glacier. I think the largest of these is the Chocolate Glacier, and I’ll show you a picture of it later – I love the name. The Scimitar Glacier descends all the way down to 5,600 feet, and the Chocolate Glacier almost as far.

The first time I decided to drive in closer to have a look was in April of 1974. Whenever I’d go down to climb something in the Cascades, I’d stop first in Seattle and visit the REI store to treat myself to some new climbing gear. I joined the co-op in 1969, and even well into the 70s they only had the one store, unlike the 162 that now blanket the US. After a shopping spree, we drove into the suburbs and slept in the VW beetle overnight. Early the next morning, we headed out of the city and drove to Arlington and then Darrington. We just kept driving back roads as high as we could until we were stopped by snow up Crystal Creek. It was April 12th, pretty early in the season, so there was snow down pretty low.

The weather was threatening, so we headed back down to Crystal Creek Campground. We set up the brand spankin’ new REI McKinley tent and stayed nice and dry as it rained on and off throughout the day. This wasn’t a bad tent back in the day – room for 4, and you could stand up in it. Heavy, though.

The next day dawned nice and clear. We drove around some and took a few photos. A couple of well-known local peaks were plainly visible from the road along the White Chuck River. Mount Pugh was 12 miles from Glacier Peak, and White chuck Mountain was 16. We could see Glacier Peak in the distance, but that far out it was just a tease.

It must have been a good enough glimpse, because by August I was back. I left my home in British Columbia and drove down to Seattle by 4:30, straight to the co-op of course. I bought a better compass, and also my first altimeter, a Thommen. Some of you younger climbers might wonder why I’d bother with such devices, but you need to remember that this was long before such things as GPS had been invented. Back then, if you wanted to climb in the back-country, you needed good orienteering skills – if you weren’t proficient with map and compass, you could get yourself good and lost, or worse. An altimeter was one more tool in the arsenal. The one I bought that day was the 21,000-foot model, which I carried from that point on and used on hundreds of climbs.

I drove out to Darrington by 7:00 PM that same evening, then to the end of the White Chuck Road where I camped for the night. This was an excellent road, which went right to the boundary of the wilderness area.

At the trailhead, elevation 2,300 feet, I had this glimpse of my objective off in the distance. That’s the old VW parked by the sign. It looked like the weather would cooperate, so this was exciting stuff. In the Cascades, weather is everything. It can change quickly, and I needed clear skies to pull this one off.

I was moving with a full pack by 6:00 AM the next morning, up the trail that followed the White Chuck River. It took me a full 2 hours to reach Kennedy Hot Springs at 3,300 feet. There, I spoke to a Forest Service Ranger about what I might expect farther on. The hot springs was just some boards surrounding a hole in the ground where hot water bubbled up. Here’s a poor picture I took.

The Pacific Crest Trail passed by this spot. This was 1974, and the PCT wasn’t officially completed until 1993.

From the hot springs, I moved on to another trail, which I followed until it was time to really start moving uphill on to the peak. I reached a spot where the trail headed up through the bush, very steeply. Someone had referred to this as the “climbers’ trail”. It switchbacked up, climbing quickly. This was a no-nonsense trail, wasting no time or energy. Its one purpose was to gain elevation in the shortest possible distance, and it succeeded. It reminded me of another such “climbers’ trail” that I had once traveled with Brian Rundle, which climbed up to Wedgemount Lake. That one gains almost 4,000 vertical feet in just over 4 miles. As Brian and I were climbing it, we met a guy coming down it who was very unhappy with the steepness and called it “a bojang trail”. We had a good laugh, and still remember the incident to this day. Well, I think the climbers’ trail on Glacier Peak was even steeper, but not as long.

By noon, I had reached treeline at around 5,600 feet in an area they called Boulder Basin. There, I had this view to the southwest to a peak known as Black Mountain, elevation 7,242 feet.

Here’s another view from Boulder Basin, a bit higher up.

Here’s one more from Boulder Basin, this time looking northwest back out to White Chuck Mountain, about 15 miles away.

The route I’d decided on to climb the mountain was to climb up the Sitkum Glacier. It wasn’t until I reached about 6,900 feet that I first set foot on the glacier proper. Here was a view of the snowfield to the south at that point.

By 2:45 PM, I had climbed all the way up to 8,100 feet, to a rocky area between the lower and upper Sitkum Glaciers. It seemed a perfect spot to bed down for the night. I felt pretty sure that I could have made it to the summit that afternoon, but I was in no hurry, so decided to kick back and enjoy my surroundings.

I was surrounded by glacier, so it was fun to walk around and take my time and see what I could see.

I relaxed, cooked a meal and watched the sun go down on the slopes above me. I was asleep by nine o’clock. The day had been perfect – many miles covered, and about 6,000 feet gained with a full pack. The weather was holding flawless, and I had a really good feeling about going for the summit in the morning.

Came the dawn, and I got ready quickly. The weather was perfect, a clear blue sky and no wind. With a small day pack, plus crampons and ice axe, I set out at 6:15 AM. I climbed steadily up the upper Sitkum Glacier and proceeded to have my mind blown by the incredible scenery. I stopped for a moment to take this picture while at 9,300 feet. The rock finger sits on the ridge between the Sitkum and Scimitar Glaciers, and is shown on the map at 9,355 feet. In the background can be seen Mount Baker, 62 air miles to the northwest.

Higher yet, I could see that I was getting closer to the top. The next picture shows the true summit on the right, while on the left we see a bump at 10,300 feet.

Once up at that bump at 10,300 feet (which was known as Rabbit Ears), I could see out to the north to that far bump at 10,140 feet on the right as seen in the next photo.

At 9:00 AM, I stepped on to the summit. There I was, on top of Glacier Peak at 10,540 feet. If you click on the link, you’ll see a map. Click on the map and it will expand, and you can see how much ice surrounds the mountain. Now, with the luxury of time, the shutter started clicking, and I get to show you the results, the photos I took from the summit. This first one shows the view to Mount Rainier, 53 miles to the south-southwest. If you look carefully, it is the double white dot right in the middle above the long horizontal band of peaks.

Every direction I looked, the view was breath-taking. To the southeast sat the Cool Glacier.

This one was looking south of east.

And here’s the Chocolate Glacier to the east. Why the name? Is it because it is covered in dirt? Is it always that way?

In this next one, we are looking north to Eldorado Peak, and although its elevation is only 8,868 feet, it is flanked by the largest continuous non-volcanic ice sheet in the lower 48 states. It’s the big white mountain on the horizon a third of the way over from the left edge of the photo.

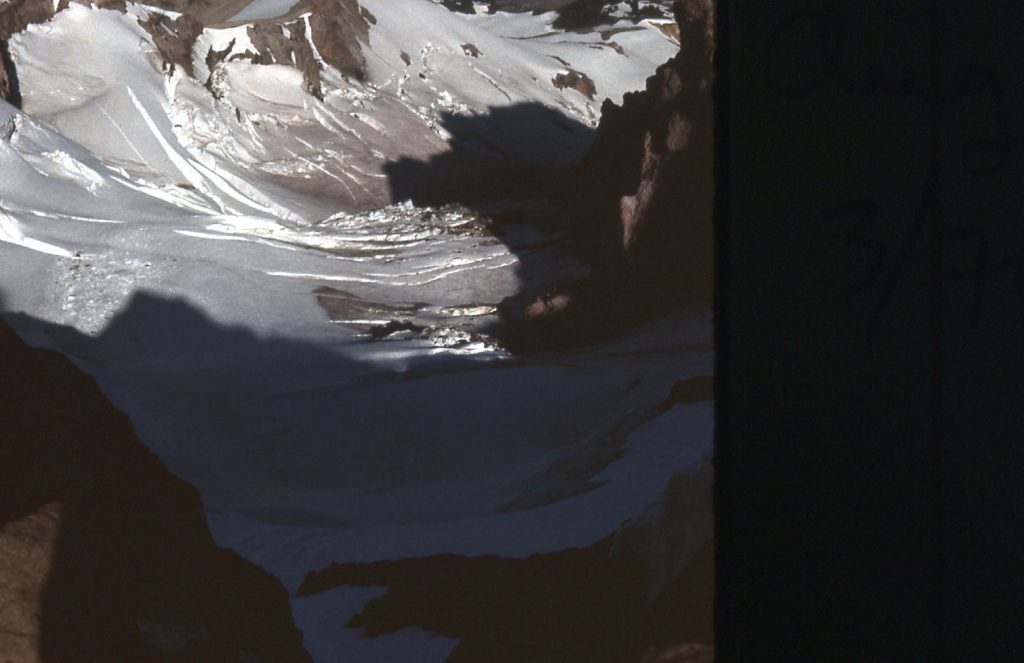

I really like this next one – we are looking steeply down to the Scimitar Glacier.

I didn’t spend long on top – I guess I felt all those miles waiting for me to get back to my vehicle and the drive home. Have you ever done a boot glissade? It’s where you stand up, both feet planted on a steep slope of snow, and allow yourself to slide down in a controlled manner, letting gravity take you. Ideally, you use your ice axe as a brake, both hands gripping it firmly and the ferrule digging into the snow behind you to slow yourself if and when needed. On this day, snow conditions were perfect – I was able to glissade down the continuous snow surface all the way back to my campsite, dropping 2,400 vertical feet in 40 minutes. Even so, I was able to stop for a bit and take these few photos on the way down.

Here’s a look back up – the summit is on the left, while the dark crag on the right is called Disappointment Peak, at 9,755 feet.

One final view to the south showed the White Chuck Glacier and the Suiattle Glacier, part of a huge sea of ice out in that direction.

I packed up my camp and kept right on going, making it all the way back to Kennedy Hot Springs just after noon, and finally to my car by 2:30 PM. This August 3rd climb in 1974 was just about perfect, everything just fell into place – it happens that way sometimes. I’ve never been back to Glacier, but I was surprised to learn, while doing my research for this story, that things aren’t the way I knew them all those years ago. I found this description online:

A major rainstorm and flood in the fall of 2003 flattened the landscape. Gone is the hand-hewn cabin. Gone are the trails and campsites. There is no sign of the springs, the bridges, corral or shelters. What used to be one of the most popular back-country areas in the region — Kennedy Hot Springs, named for that errant trapper — has been inundated with mud, woody debris and a ragged mess of rock and exposed gravel. The White Chuck River cuts a path through the terrain and is joined by Kennedy Creek in what is now a jumbled flood plain.

I guess the approach and route I used back then have been wiped out, so climbers nowadays are probably forced to use other routes – it’d be a completely different mountain for them. I’m glad I had the terrific climb I did.