The United States had a problem back in the early 1800s – as the west opened up and settlement grew in California, it took an unrealistically long time for mail to travel from one coast to the other. Before the transcontinental railroad was built, mail from New York City to San Francisco had to travel 14,000 miles by ship around Cape Horn and took a full 200 days, one way. That’s more than half a year! It hardly seems worthwhile, does it? There had to be a better way.

John Butterfield was a man who had 37 years of experience working for and running stage lines when he was awarded a contract by the Postmaster General of the United States in 1857. The contract was for $600,000.00 per year for a twice-weekly service between St. Louis and San Francisco. Before service could begin, though, the route had to be laid out clearly over its 2,795-mile course. That meant establishing reliable water supplies, providing at least simple facilities at the stage stops, building bridges and taking care of a myriad of other details. Eventually there were a total of 175 stations along the route.

As well as the mail, the stages carried passengers, and it was not a luxurious means of travel. At each station, there would be a brief stop to change horses, coach and driver. Passengers would have to sleep on the stage while it rolled along the bumpy, dusty route. By today’s standards, it would have been one hellacious ride indeed. The trip lasted 25 days, and the service ran until 1861.

The Butterfield Trail ran for a distance of 437 miles across its Arizona portion and included a total of 25 stops. Pretty much all traces of those stations have disappeared, but there is one spot where a few remnants survive, and that was my goal one winter’s day – to pay a visit and see what I could see.

A nice paved road runs between the towns of Gila Bend and Casa Grande, nowadays known as Arizona State Route 238. I drove it to a point near a railroad siding with the name Estrella, no doubt named after the very prominent mountain range to the northeast called the Sierra Estrella. A dirt road led north into the desert at this point, so I thought I’d try it and see where it took me. An unlocked wire gate was soon passed and away I went. The road meandered a lot across the flat desert terrain, following the path of least resistance. Not 4WD, but definitely high-clearance in places. Five miles of northward travel at around 1,600 feet elevation brought me to my destination.

Another dirt road ran directly across my path, this being the track that the topographic maps all clearly labeled “Butterfield Stage Route”. Twenty-seven miles, that’s it. A mere 27 miles of undisturbed track is all that survives. At either end of the 27, the route is truncated by highway, cropland, Indian reservation and other signs of civilization. Modern Man must have felt that these lonely miles weren’t worth fighting over, so left them alone. I was excited to see what I’d find as I made a hard left turn on to the worn-out old road. I was soon to learn that this old trail wore many hats, this being the first.

I know it’s hard to read the fine print on the sign, so I’ve written it here for you so there’s no need to strain. It says:

Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail

If you had been standing here in the fall of 1775, you would have witnessed an amazing sight. You would see the dashing Juan Bautista de Anza, captain of the Spanish crown’s Royal Presidio at Tucson leading the main group on a fine horse. Father Pedro Font and two other padres came next, probably mounted on humble burros. Then came the main group of colonists and uniformed soldiers together with their wives and children, some mounted and some on foot. The rear guard of colorfully uniformed soldiers (soldados de cuera) with their long lances, heavy broadswords and short flintlock muskets were assigned to ride as protection along the trail and in the new settlements. Native American interpreters were an important part of the expedition since they would be traveling through so many different tribal territories. The muleteers, vaqueros, servants, supplies, personal belongings, tools, equipment and over 1,000 head of livestock made up the remainder of this long, noisy and dusty procession.

The segment of trail before you represents only a small portion of an expedition of over 1,000 miles that these brave people undertook. Stretching from Sinaloa and Sonora to Alta California, the opening of this trail marked the beginning of a successful land route to the new missions, presidios and settlements being established there.

I love the elegant flourish of de Anza’s signature in the lower right corner of the sign, so typical of Spaniards of the era.

I had barely started along the trail when I ran into the above sign, within a few hundred yards in fact. It was obviously there to greet folks such as myself, the curious who had come to steep awhile in a bit of history. Moving on, this next sign soon greeted me, informing that the trail had served many other purposes.

Here’s what it says:

Southern Overland Route

Native American trails

Spanish trails

Gila Trail

Pioneer trail

Mormon Battalion Trail

Forty-niners trail

Butterfield Stage Route

Just imagine the traffic you’d have seen if you’d been a Saguaro cactus growing alongside the trail for 200 years, mute witness to the westward migration.

All along the trail were signs such as these, marking the boundary of the wilderness area which occupied all of the land on the north side.

These signs were also commonplace along the route.

Here is a view of the trail, along one of the nicest, smoothest stretches.

I passed this sign, but was unsure of its meaning. Did it indicate that present-day people were meant to camp here, or did it indicate something from the past?

The topographic map which covered this part of Arizona was called “Butterfield Pass”, and before long I rolled up to the pass itself. The metal gate you see in the photo marks the spot – it wasn’t locked, and I simply pulled it open in order to pass.

Other than the gate itself, there wasn’t anything at this spot, deep in the heart of the northern part of the Maricopa Mountains. It’s easy to see, though, why all those early travelers chose this place to pass through the mountain range. The slope to both west and east of the pass is gentle, and this narrowing through the mountains is less than 2 miles in length. It is a pretty spot, with mature trees growing along the wash that drains the pass. At its western end, things widen out and that’s where the Butterfield Stage Line chose to put its station. Every station had a name – this one was no exception, and was known as Desert Station.

There are things of interest nearby. Arizona Game and Fish has established a device to collect rainwater, store it in an underground tank and dispense it at a drinker for wild animals.

Here’s where the animals drink.

I found this unusual sign honoring the Mormon Battalion. Click the link for some fascinating reading.

Here are close-ups of both top and bottom of the sign.

Here’s another obvious feature that stood nearby. What is it?

Here’s a view inside it. It must be important to have had a fence put up around it.

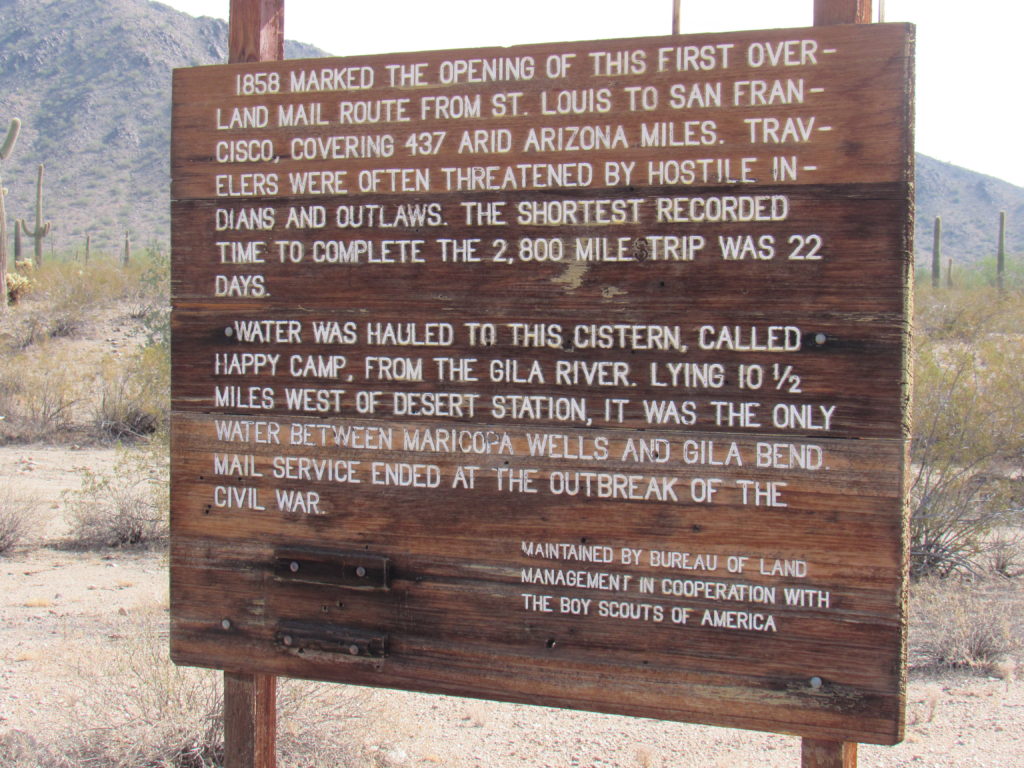

This nearby sign helped explain things – it appears that it served as a cistern back in the day to store water for the stage line.

Next to the sign was a watertight metal box with a sign-in book. Serving much the same purpose as a climber’s register on top of a mountain, the Bureau of Land Management hoped that all passers-by would sign in so they could get an idea of how much traffic this place saw.

So all this stuff was part of or near the Butterfield Stage infrastructure here known as Desert Station. When you think of all the various groups that used Butterfield Pass as their travel route back in the 1800s, this must have been a (sometimes) busy, important place.

I thought I’d try for the big picture, an overview of it all, and what better way to accomplish this than climb a mountain. Conveniently, one stood nearby that would give me a bird’s-eye view of Desert Station. In fact, Peak 1962 sat right across the road.

It didn’t take long to climb the 450 feet to the summit where I found the register left by others. I got the view I wanted, alright. In this next photo, the remains of the station are in the lower right corner down on the flat desert. Don’t strain, you won’t spot them.

After a while spent on top admiring the view and trying to imagine travelers passing through the desert below almost 200 years ago, I considered the fact that the Butterfield Stage departed San Francisco twice a week and St. Louis twice a week. That meant that 4 times a week, the stage rolled into the station below in a cloud of dust. The travel-weary passengers would disembark for a few precious minutes before boarding again and continuing their bumpy ride.

I made my way back down to the station and prepared to leave. It had been a fascinating dip into history. Nearby Butterfield Pass may be the only place actually named after the stage lines. The USGS topographic map of the area is in fact named “Butterfield Pass”, so those are 2 significant nods to the stage lines. A short distance from Desert Station was this one last sign.

In case you can’t read it, here’s what it says:

HISTORIC TRAIL

The path you are standing on is an important connection to our past. Please help conserve this fragile path through history. Drive only on existing roads. Foot travel only on fragile historic paths. Leave what you find and preserve this historic path for others. Thank you. Enjoy your public lands!

Just over 3 miles farther southwest along the Butterfield Trail (the road was very flat and quite good), I came to a spot known as Gap Well. It appears that this metal and masonry tank had been built for the purpose of holding water for cattle, long after the Butterfield Trail had ceased to be used.

It was here that I left the Butterfield Trail behind, instead heading southeast on a good dirt road to get back to the paved highway. I hadn’t gone but a mile from the well when I thought I spotted something moving on the road up ahead. I drove closer, slowly, to get a better look. When I knew for sure what it was, I stopped my truck and got out. Here’s what I saw.

I was shocked, and delighted, to see this elusive creature. The American badger is the only species of badger found in North America. Click on this link to learn all about it. Only one previous time had I ever seen one in the wild. It was 25 years ago when my wife Dottie and I saw one by a farm field in Saskatchewan. In Arizona, they are found in every habitat, from the hottest deserts to the highest mountains. Still, though, they must be extremely elusive for this to have been the first one I’d ever seen in 35 years of roaming the wilds here, unless I’m incredibly unobservant. In any case, seeing this one made a bigger impression on me than the 7 miles of the Butterfield Stage Route I’d traveled. The badger posed momentarily for the photo, then ambled off into the desert, seemingly unconcerned. My day was truly complete.