Please read Chapter One of this story before starting this one.

Where we had left off, I was on a bus which had just pulled up in front of one of the ships at the pier in Ushuaia, Argentina. So now my secret is out. The main reason that passenger ships are ever in that city is because they are going to Antarctica – not always, but usually. That was the case for me – a trip to that frozen continent was what was on my bucket list. Here’s a picture of my ship.

I don’t know what kind of impression you get from the picture, but this ship was no huge ocean liner the likes of which you see advertised on television. I’ll tell you a few things about her.

She was built in Norway for a company called Hurtigruten. These guys are no strangers to cold polar waters – they’ve been sailing since 1893. The ship was named for Roald Amundsen, the Norwegian who was the first man to reach the south pole and also the first to sail through Canada’s Northwest Passage, so it felt right away like the ship had a good pedigree. She was built for sailing through polar waters, and is rated as Polar Class 6, meaning that she is “designed for summer and autumn operation in medium first-year ice which may include old ice inclusions, up to 3.9 feet thick”. She is 459 feet long, has 11 decks and weighs 20,890 tons. When sailing in Antarctic waters, she carries a maximum of 500 passengers. On my trip, we were only 368 passengers with a crew of 120. The ship is hybrid, meaning that she can sometimes power herself with the use of huge banks of batteries. She runs very quietly, with little vibration. She uses no anchors, instead using a dynamic positioning system.

If you look at the above picture, see the white thing down close to the water level? That is where we got on to inflatable boats to go on shore excursions. Look above that to the first row of windows in the black area of the ship – my cabin was there, on Deck 4. It was a good spot, down low and midships, the best place to be to avoid motion sickness in rough seas. The ship looked and felt very Scandinavian throughout. Because she was built for expedition cruises, life aboard was casual. No dressing up for dinner, no jacket and tie, ever, and I really appreciated that.

When we got off the bus and boarded the ship, the crew was there checking our ID and then asking for proof that we were vaccinated for Covid – they were very strict about that. We were each assigned to a small group of about a dozen people, and our group was named after a bird or mammal found in the Antarctic. My group was the Crabeater Seals. We were each given a jacket to keep, windproof and waterproof, which we were to wear every time we went ashore. Also, we would attach to our jacket a badge which identified our group. This was a part of the ship’s efforts to keep track of everyone who was going ashore, which we did eleven different times while in Antarctica.

Soon after boarding, we went to our muster stations where we went through a comprehensive safety drill. One of the crew showed us how to don a special suit which covered us from head to foot, designed to help you survive in the frigid ocean water for a while in case we had to abandon ship, God forbid! The suit looked a lot like this one.

With that pleasant image still fresh in our minds, we then went and settled into our cabins.

Our ship pulled out of the harbor in Ushuaia and headed east along the Beagle Channel which was named after the ship HMS Beagle which passed through the area in 1826 with the naturalist Charles Darwin aboard. At first I was puzzled as to why we were heading east. For some reason, I thought that the shortest way to Antarctica would be to head south from Ushuaia along the west side of Navarino Island and pass by Cape Horn. My desire to actually see Cabo Horno was so strong, all my life I had wanted to see that famous spot, that I just assumed that’d be the way we’d go. I’ve since learned that sailing south between the islands to reach the cape is trickier than heading east through the Beagle Channel like we were doing. It became apparent that visiting the cape just wasn’t a part of our agenda on this trip.

The ship served a nice buffet supper in their main dining room that evening as we headed east. We had to travel about 70 miles through the channel before swinging south into the open waters of the Southern Ocean, so that was a good 4 hours at our normal cruising speed. The captain announced that around midnight we would leave the channel and enter the Drake Passage, and that we shouldn’t wait until then to take any sea-sickness medication we might have brought along. He said to take it hours ahead of time so we’d be prepared for the rough seas we’d encounter during the night. Good advice, I thought – I took a Dramamine tablet, then another one a while later just for good measure, and turned in for the night.

During the night, I could definitely feel the ship moving around a lot as I lay in bed, and I couldn’t help but wonder what the morning would bring. I awoke at 6:00 AM to stormy seas. My cabin window was on Deck 4, and I figured it was a good 30 feet up from sea level. Spray was washing across my window – some of it was wind-borne, but at times the waves reached up to my window and even higher. Here is a video I took to give you an idea of what we were experiencing.

So what’s the big deal about the Drake Passage, you might ask. Well, allow me to entertain you with a few facts and figures. All my life, I had heard stories about how rough a stretch of ocean it could be, so it was with some trepidation that I had looked forward to experiencing it for myself.

If you look at a map of the world, or, even better, a globe, you will see that there is a stretch of open ocean below South America, stretching south for over 600 miles. There is no land from Cape Horn, at around 56 degrees south latitude all the way down to the South Shetland Islands, where we find Livingstone Island at around 62 degrees 30 minutes south latitude. This same open stretch of water runs all the way around the globe at the same latitude, unbroken by any land mass. It is the only place on our planet where winds can circulate without anything in their path all the way around the Earth. Both air and ocean currents meet with no resistance here, traveling from west to east. This body of water is named after Sir Francis Drake, an English explorer who did circumnavigate the world but barely touched the northern edge of the passage itself in 1578.

Mariners refer to the southern regions of the ocean with some colorful terms: the roaring 40s, the furious 50s and the screaming 60s. Nineteenth-century whalers who plied the Southern Ocean had a great respect for the stormy seas, and came up with this saying: “Below 40 degrees of latitude, there is no law; below 50 degrees of latitude, there is no God.” And here we were, venturing well down into the 60s. What would we encounter?

The waters of the Drake average 11,000 feet in depth, and are as deep as 15,600 feet. The eastward flow of water through the Antarctic Circumpolar Current carries up to 5,300 million cubic feet per second from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic Ocean. Huge waves of up to 60 feet have been recorded. They say that you might get lucky and experience calm waters in the Drake, or very rough conditions – the Drake Lake or the Drake Shake. The day I made the video posted above, the bridge crew said that the wind was gusting to 68 knots, or 78 miles per hour, and that the ocean swells were up to 10 meters, or 33 feet (that’s why waves were washing over my cabin window). The bridge was way up on Deck 9, and I was lucky enough to visit it that day. It was all I could do to stand up without holding on to anything for support. Huge amounts of wind-driven spray were sloshing over the bridge windows, and they had to frequently operate large windshield wipers to clear them. The captain described the conditions as “a moderate day” on the Drake. There were periods of better weather during the crossing, and the ship’s photographer managed to take some photos of birds out on the ocean.

The only icebergs I had ever seen were smaller ones floating on lakes in Patagonia, so imagine my excitement upon seeing this one, my first “real” iceberg, out in the middle of the Drake.

When we first entered the Drake, we were heading south on a bearing of 165 degrees. About half-way across, the captain changed to a heading of 190 degrees. The crossing takes quite a while. For us, it was the night of January 8th, all day of the 9th, the night of the 9th, all day of the 10th. Sometime that day, we found ourselves heading down the west side of the Antarctic Peninsula, which we did all day and then through the night of the 10th.

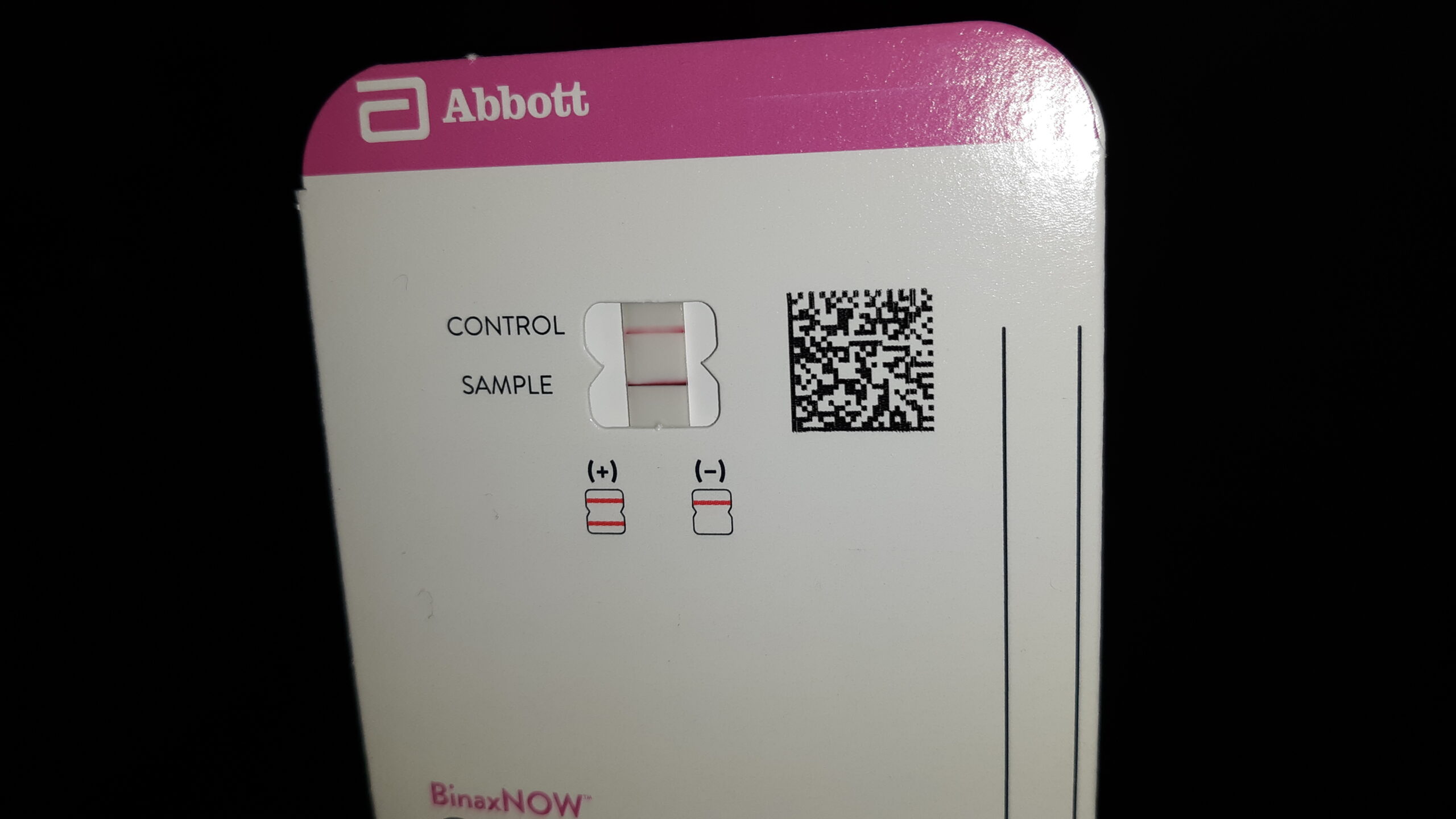

During the night of the 9th, I woke up and sneezed a few times and had a runny nose. That was unusual for me, so on the morning of the 10th I decided to do a Covid test. I had brought a few along with me, just in case. The result was immediately strongly positive. Here’s what such a result looks like.

Dammit, I knew that this was going to cramp my style. I called the ship’s doctor and told them what I had discovered. A medic came to my room and ran their own test on me, which showed a strong positive result for Covid. It was Wednesday, and they said they’d need to confine me to my cabin for a few days, and that’s what I expected.

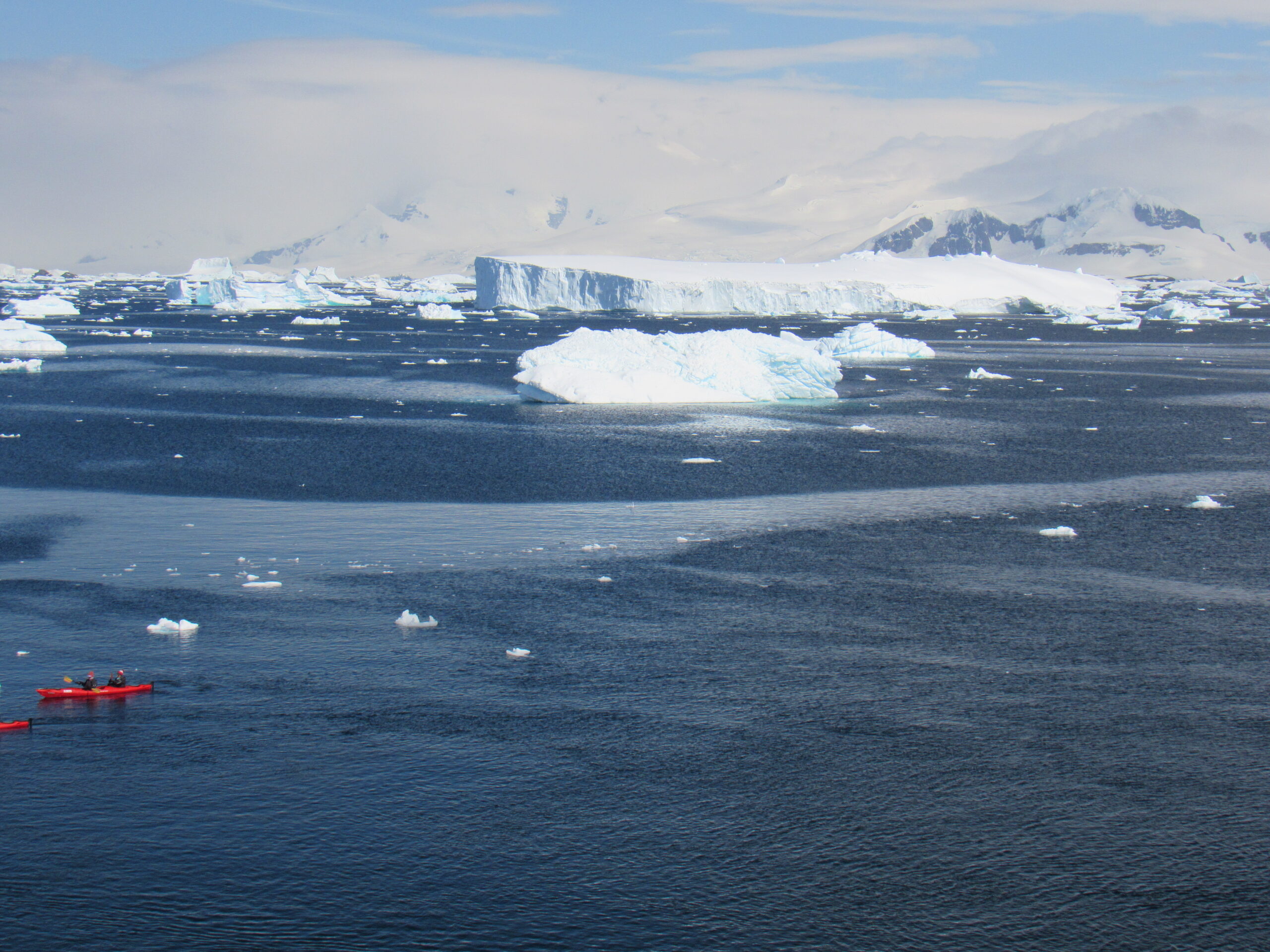

There was an app we all downloaded to our cell phones upon boarding the ship which told us what the offerings would be for every meal. I could decide ahead of time what I wanted to eat, the kitchen would call me for my order, and a member of the crew would bring the food to my room. It was great. My symptoms were very mild, I slept well that night, and the next morning I felt great, with no symptoms at all. The doctor and a nurse came by my room to see how I was doing and were pleased to see my progress. They allowed me to go up to the top deck of the ship, Deck 11, which was outdoors, so I could get some fresh air, but limited me to 30 minutes. The weather was fair when we stopped at a place they called Crystal Sound. Passengers went out in the Zodiacs, the inflatable boats we used for shore excursions, but didn’t actually set foot on shore, instead cruising around the bay and enjoying the scenery. Here are some pictures of that day, a combination of ones I took and some taken by the ship’s photographer.

The air temperature was 40 degrees F. at noon. Once all of the zodiacs and kayaks had returned to the ship, we set sail in worsening weather in the afternoon. By 8:00 PM that evening, in gloomy, overcast weather we reached a place called Martha Strait. The ocean was frozen over, and the ship nudged up to the sea ice. The captain chose to stop here because it was a rare opportunity for a walk on the frozen ocean. In order for us to do that safely though, the ice needed to be at least 50 cm thick. Some of the crew went on to the ice to test its thickness.

It was thick enough, so teams were organized and took turns walking out on to the frozen ocean. Any time the passengers ventured off the ship, we were shepherded by the ship’s expedition team, seen here. They always wore yellow jackets so they plainly stood out from the passengers.

Here is the bow of the ship at the ice.

Here was a view of the ice seen from the dock where we disembarked.

A real bonus of stopping here was a lone, immature emperor penguin standing on the ice. This was totally unexpected, because the usual places you’d expect to see one were hundreds of miles away.

This picture shows an area marked by flags which indicated where we could safely walk.

Out on the ice. The black straps are part of the life vests we always wore when going ashore. The man on the far right shows the front of the vest.

Stopping here was special for another reason – it was the first place we enjoyed that was south of the Antarctic Circle. Geographically speaking, the circle is located at 66 degrees 33 minutes 47.5 seconds south latitude. Our location here at the sea ice was 66 degrees 43 minutes south by 067 degrees 6 minutes west. We had actually been south of the circle all day, since 9:55 AM that morning. Later on, I’ll discuss the importance of the Antarctic Circle in greater detail.

The pictures taken at the sea ice were up to ten and eleven o’clock in the evening, so you can see that it didn’t get dark even late here in these southern latitudes in the summer months.

The ship’s doctor decided to move me from my window cabin on Deck 4 up to one with a balcony on Deck 7, so I could easily get fresh air while in quarantine. A crew member helped me move a few essentials for my temporary stay up to my new digs and I settled in. It had been a good day, and I was excited to see what was next on our agenda, so stay tuned, Folks.