Worth it?

When facing a big, difficult climb, each time you need to ask yourself: “You could die up there. Is it worth it?”

Cartel Gear

Many’s the time I have come across radio gear on mountaintops here in the desert. Some of it is Border Patrol or other government equipment, and as such is usually plainly marked. However, plenty of it has been put there by scumbags working for the Mexican drug cartels, and it never has any identifying markings. Whenever I find cartel gear, I do my best to make it unusable. There will usually be a car battery to power the radio, and I’ll take the battery to the nearest spot where I can throw it over the edge so it will smash below. I’ll rip out any wires and throw them away. Usually there’ll be a solar panel to recharge the battery, and they make good frisbees when hurled into the abyss. I’ve destroyed stuff like this plenty of times, and it never fails to satisfy.

Cinder Mountain

One time years ago, I got a wild hair to go and climb a small peak out in the middle of nowhere. This one was way out there, beyond beyond, and I was pretty sure it hadn’t been visited by any climbers. Surveyors had been there and left a benchmark back in 1948, but since then, nothing. Why was I so confident climbers hadn’t been there? Well, the simple reason was that it was in a part of the Air Force bombing range where they regularly would shoot at things and drop bombs. Climbers tend to avoid areas like that for their health, and you certainly can’t blame them. However, the simple fact is that peaks out in forbidden places like that are often the juiciest prizes. Cinder Mountain was just such a prize.

I spent the night at the edge of the bombing range, and long before sunup I rode my mountain bike along a paved military road for miles, then headed across open desert for miles more. When I reached the base of the peak, I just left the bike lying there and got ready to climb. That’s when I noticed a small snake coiled up on the ground right by the bike – I had almost stepped on it. It was a small sidewinder rattlesnake, not over a foot long – small but deadly. I stepped gingerly around it and started up the slope. The climb was only 210 feet, and when I topped out, I found myself on a very flat summit. It was pristine. Still not much past sunrise, the quiet was almost overwhelming. It didn’t take long to find the benchmark, and then I sat and soaked up the solitude of the place. Perhaps I spent a bit too much time up there, because by the time I was riding the bike back along the paved road, I had a close encounter with a military vehicle. They must have seen me, but I fled into a brushy area with the bike and avoided them, just barely.

Un-marked Route

Brian and I were climbing a big volcano on the Chile-Bolivia border. We had given ourselves an absolute turn-around time, meaning that no matter how close to the summit we were, no matter how tempting it would have been to continue on up higher, we would honor that time and turn around and start back down. Well, we reached our summit a bit ahead of the agreed-upon time, and started back down a bit ahead of schedule.

The mountain was huge, and we had climbed almost 4,000 vertical feet in one push on summit day. We hadn’t marked our route in any way, not with wands or anything else. It was ice and snow nearly all of the way up, and there were no distinguishing features along our ascent route. This was years before GPS or any of the other electronic aides that nowadays can keep a record of the exact path you travel. We made it back down to our tent just as the last daylight faded. In retrospect, if we had been benighted higher up on the mountain, there was no way we could have ever found our fly-speck of a tent in the dark. It would have been one cold night spent up there on the glacier with no tent or sleeping bags, just the clothes we were wearing.

Chullpas

We had hitched a ride across the Altiplano with a fellow driving an 18-wheeler. He pointed out some strange-looking structures off to the side of the highway and said they were called “chullpas”. Curious things they were, made even more so by learning their purpose. They were ancient funerary towers, originally constructed by the Aymara people for a noble person or a noble family.

They are found across the Altiplano in Peru and Bolivia. The ones farther north were made of stone and were circular in shape. Those farther south were rectangular and made of stucco. The ones in my photo appear to be the latter type. Corpses in each tomb were typically placed in a fetal position along with some of their belongings. The only opening in each chullpa faced the rising sun in the east. The tallest of these stood almost 40 feet. Some of them were possibly used by the Incas after their conquest of the Aymara.

Say What?

Something I’ve always hated about technical climbing is being unable to communicate with the person on the other end of the rope. Now to be clear, I’m never the one leading a climb – I’m always second, at the tail end, following the leader. The guy out front may disappear from sight as he goes around a corner, or up over a bulge. If it’s windy, that makes it even harder to hear each other, as the wind usually seems to blow away your words. In any case, if you can’t communicate with the leader, it can be very difficult to know what to do next. You may need to give him slack, or put tension on the rope, or any number of other things. I’ve found it very stressful in the past to deal with this problem, so much so that at times I didn’t know whether to shit or go blind. Finally, a fairly simple solution presented itself. I got a pair of those little FRS 2-way radios – I carry one and so does the leader. Either of us can just press a button and speak, and the other can hear them clearly. I’ve used them several times, and they work like a charm. Problem solved.

Food Fantasy

If you’re on a lengthy climb and are tent-bound for days due to bad weather, it’s easy to start fantasizing about the food you’d love to eat but can’t because you’re stuck out in the middle of nowhere. Here is something funny that was said by a climber in such a situation:

“If I had some ham, I could have ham and eggs, if I had some eggs.”

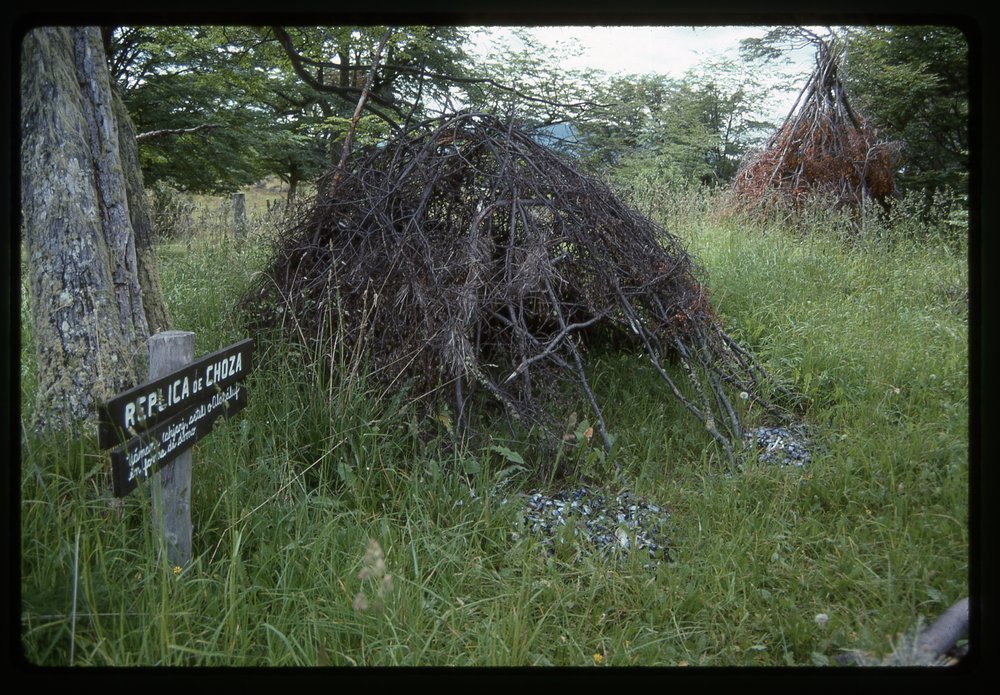

Choza

Have a look at this photo, taken at Harberton Ranch in Tierra del Fuego. It is the southernmost ranch in the world.

You are looking at a choza, or at least the re-creation of one. It is a primitive shelter that was used by the Selk’nam people who occupied the area. These were the hardiest of people, who survived the harsh winter climate with almost no clothing. They were virtually exterminated by the European settlers who moved into the area. The last full-blooded Selk’nam tribesperson died in 1974 and, by 1990, there were no longer any Ona-language speakers left in the world (Ona was the language they spoke). Today, only a few hundred people still identify themselves as Selk’nam descendants.

Noisy Tent

What could cause a tent to be noisy? Wind, that’s what! There are some pretty amazing tents out there, with hi-tech frames, fabrics and tie-downs. The best of them can shed rain and snow very well and keep you safe and dry. However, at the end of the day, if a storm is strong enough and long enough, it can destroy a tent. In the process, powerful winds can cause a tent to flap so hard that the noise can be almost deafening. There’s no sleep to be had in such a storm. You find yourself praying that the tent doesn’t shred or that poles aren’t broken during such an onslaught. Many’s the climb that had to be abandoned when a powerful storm destroyed a tent, leaving retreat as the only option.

Snow Load

If you’re in a tent and it snows, you need to prevent the snow from building up on your tent. Some tents shed snow quite well, but eventually any tent will succumb to snow piling up on it. You may need to go outside and brush or shovel all of the snow off from time to time. It’s amazing how much snow can accumulate overnight during a mountain snowstorm. If the snow is fairly wet, it will be heavy and will collapse your tent, breaking the poles or tearing the fabric. If you don’t keep the snow cleared off of the tent, it will push the walls inward and you’ll find your world shrinking. If the inside becomes damp, it can soak your gear, making for a miserable experience.

You might want to build a snow wall around your tent, to keep drifting snow from building up against the tent, but that may not help much – the wind direction can change constantly. Even the world’s best tent can be destroyed by too much snow if you don’t manage it properly during a storm.

Stealthy Border Patrol

A few decades ago, I decided to go out and climb a peak that was down close to the Mexican border. I parked my truck in an out-of-the-way spot and headed out on foot, wearing a light day pack. To reach the peak itself, I had to cross a couple of miles of woodland that was fairly open. I had been walking along for a while, and when I was in an open stretch with no trees, I had an urge to turn around and look behind me. Imagine my shock to see a man close behind me, only 50 feet away, who was following me. He approached me as I stood and waited for him, and I saw that he was wearing a Border Patrol uniform. He was armed, and I was not. He asked me who I was and what I was doing there. When I told him I was a climber and was on my way in to climb a nearby peak, he seemed relieved. He proceeded to tell me that it was a dangerous area, that plenty of illegal activity took place there – Mexican drug cartel members were bringing in loads of drugs and groups of undocumented immigrants. He told me to be extremely careful, and that it would be wise to carry a firearm in such a place. He had a radio, and made a call to his fellows to tell them that everything was okay, that the incident was a Code 4. At least I think that was the code he used, and he said it meant that it was a friendly encounter with a US citizen who was not breaking any laws. I complimented him on his stealthiness, admiring how he got so close to me without my knowing he was even there. He appreciated the praise, and said that they got a lot of practice. He said to remain vigilant and be safe, and he went back the way we’d come in while I continued on to my peak.