So here we were, Jake and I, traveling the Camino del Diablo. Did I mention his truck? It was a Chevy Silverado Trail Boss, a very classy ride. The cab was big, with a rear seat for all our gear. The truck had every luxury you can imagine, and we rode in comfort while listening to oldies from the 50s and 60s that Jake had loaded into his sound system.

We had left off in the first part of this story at our arrival at Boundary Camp, an outpost of the US Border Patrol. The place was quiet with no activity that we could see, so we moved on. About 3 miles past the camp, we came to San Cristóbal Wash. This watercourse is bone-dry 99% of the time, but in the rare occurrences of a heavy rainfall, it can flow freely. Such was the case when I tried to drive through it in October of 2014, the day after the remnants of Hurricane Simon struck. Water was running across this stretch shown in the photo and it was two feet deep. The abundant vegetation shows that water is actually present here at times.

Four miles beyond the wash put us in Cholla Pass, so named because it is endowed with a dense stand of five cholla species. Two miles beyond that we came to Chinaman Flat. It’s nothing but a piece of flat, scruffy ground, and I was curious how this place got a name of its own. One source says that Chinese immigrants wished to farm the area. Another story says that they were smuggled into the country and then murdered here. Apparently several defunct wells are in the vicinity.

Just to prove to you how much water fell from the sky that time when Hurricane Simon came through, here is a picture I took of the Camino where it passes through Chinaman Flat back in 2014. This was an extremely rare occurrence.

The Camino takes a big bend to the north near Chinaman Flat to get around the bulk of Sheep Mountain, which sits just to the south of the road.

Once past the mountain, our Camino swings back around to the southwest, and we can see Papago Mountain ahead of us, also on the south side of the road.

At the 39-mile mark, we reach a major feature which is well-known to travelers of the Camino. This is Papago Well. It was drilled prior to 1909 to serve operations and crew at the nearby Papago Mine and Legal Tender Mine on the west side of Papago Mountain. One source says it was drilled to a depth of 235 feet. It appears that a solar panel provides power to pump water up and into the large metal tank, which still provides water today to passers-by.

This sign tells you how far it is to go to Tule Well, one of the major features farther west along the road. Cell-phone coverage here is hit-and-miss, but the sign indicates you could at least try if you were in trouble.

The Camino here is along the north side of the Agua Dulce Mountains, and just south of the well sit a couple of small bumps known as the Davidson Hills, apparently named for Bill Davidson, who was a head watchman for the Phelps Dodge Mining Company.

Tule Well sits at an important junction. A road heads south into the heart of the Agua Dulce Mountains and down to the Mexican border. Another road heads north into the Mohawk Valley, passing between the Sierra Pinta and the Antelope Hills, then along the west side of the Bryan Mountains, and finally leaves the Cabeza Prieta Refuge after 32 miles to enter the Barry M. Goldwater military range.

It was 12:30 PM when we left Tule Well and continued west on the Camino. At around 43 miles into our journey, we arrived at another Border Patrol station, known as Camp Grip. This had been a busy place for years, a real going concern, so you can imagine our surprise when we arrived and saw that it was completely shut down.

I later learned that the camp had been shuttered only a month before our trip, in January of 2023. The agent I spoke to in Wellton, Arizona told me that “they just didn’t need it anymore”. He should know, as this camp was staffed from the Border Station in that town.

Only a mile past Camp Grip, we arrived at O’Neill’s grave. This is the last resting place of David O’Neill, a prospector whose “burros wandered away from camp in a storm, and after searching for them at least a day, he died with his head in a mud hole.” By one report, the two men who buried O’Neill were friends of his, prospectors by trade, and rugged, practical frontiersmen. They divvied up O’Neill’s valuables and then covered him with dirt and rocks. A couple of weeks later, they ran out of tobacco and remembered that they had buried O’Neill’s tobacco with him. They returned to the grave and retrieved the tobacco pouch, one reporting that it “chawed just as good as if it had been in my pocket all them two weeks.” The gravesite has been plundered at least three times since then without reward. You can’t miss the grave, it’s only ten feet off of the road.

It seems customary to leave some small token on the grave if you pass by. People have left coins, bullets and other mementos. I found coins from the US, Mexico and Canada. We left pennies.

O’Neill Pass was nearby, and the grave is in the midst of the O’Neill Hills. This is Peak 1070, just north of the pass.

O’Neill has 2 features named after him, and that’s pretty good recognition, because it’s official and forever – few of us will be so lucky in our lifetime. Once you’re west of the O’Neill Hills, you enter the Tule Desert, a vast, desolate land between the Sierra Pinta on the east and the Cabeza Prieta Mountains to the west. This desert extends north for about 27 miles from the Mexican border.

About 4 miles west of O’Neill’s grave, I took this picture looking south to Cerro Pinacate, a dormant volcano which rises almost 4,000 feet above its surroundings. It is in Mexico, about 22 air miles south of this part of the Camino. It is the source of a sea of lava which made its way all the way to the US border and across it, even to the north of the Camino.

Soon after I took the above photo, the Camino entered a special area as we continued west, one we had eagerly anticipated – we started to drive across the Pinta Sands. This next photo shows the view looking north. See the color of the sand, a pinkish-yellow color. The distant Sierra Pinta shows 2 distinct colors: the light-colored peaks farther north are a blond granite, while the nearer, darker part of the range is a black gneiss. This represents the classical horst and graben geology of the Basin and Range Province. The name of the range means “speckled” or “painted”. The range high point, known as Pinta Benchmark, is 13 miles away and rises to 2,950 feet, and is way north in the light part,

Recent rains must have been substantial, because these ruts showed how soft the road had become when somebody drove through. Ruts like these will be there a long time because the mud will dry and harden like concrete.

Signs like this one reminded us that we were in a wilderness area, with the Camino cherry-stemmed through it.

A patch of hedgehog cactus in bloom added a bit of color.

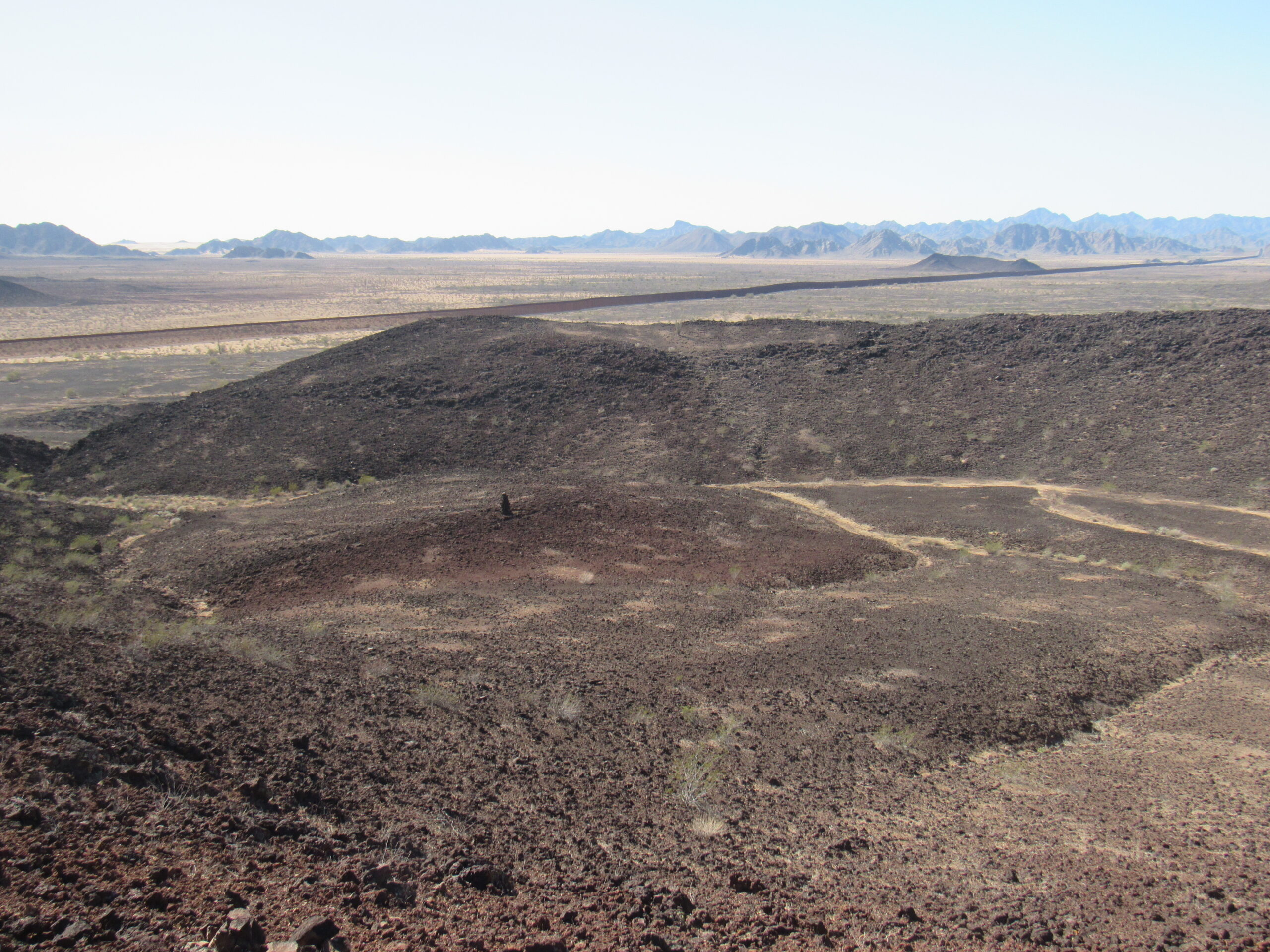

We crossed a belt of the Pinta Sands, then came to the Pinacate Lava Flow. The Camino crossed this for a few miles, and by the time we had traveled to around the 54-mile mark, we pulled off the road and parked on the south side of a curved crater. We chose this spot to camp because it was secluded and it also placed us ideally to go and climb a nearby peak known as Monument Bluff. Jake kindly obliged me to camp here and do the climb – all the times in the past I’d been through here, I’d wanted to spend more time at the lava beds, but always seemed in a hurry.

We got ready and left camp just before 2:00 PM, then walked across the flat lava and up the northeast side of the peak. We were about 45 minutes to the top. There are a number of important things I’d like to show you about this area, but you’ll need to click on the above link to start. Once you’ve clicked on it, you’ll see a small map. Click anywhere on the map and a big map will open up. You can use the +/- buttons on the upper left to zoom in or out. Please click on the – to zoom out to see the bigger picture.

The yellowish color on the map is used for the lava. You can see the Pinta Sands in a huge arc around the outside edge of the lava, stretching about 20 miles. In several places, you can see the words “Pinacate Valley” – that is an error, because that is the lava flow, which sits above the surrounding land and not below it. About 1 kilometer to the northeast of Monument Bluff sits a semi-circle just south of the road, and that’s where we camped. Here are photos to show you what we saw and did.

The climb itself was only 200 vertical feet, but it was fairly steep, as seen here.

We saw two distinct types of lava. This kind is called pahoehoe, and it has a ropy texture.

The other kind was rough and jagged, and is called aa.

Here is the top of Monument Bluff.

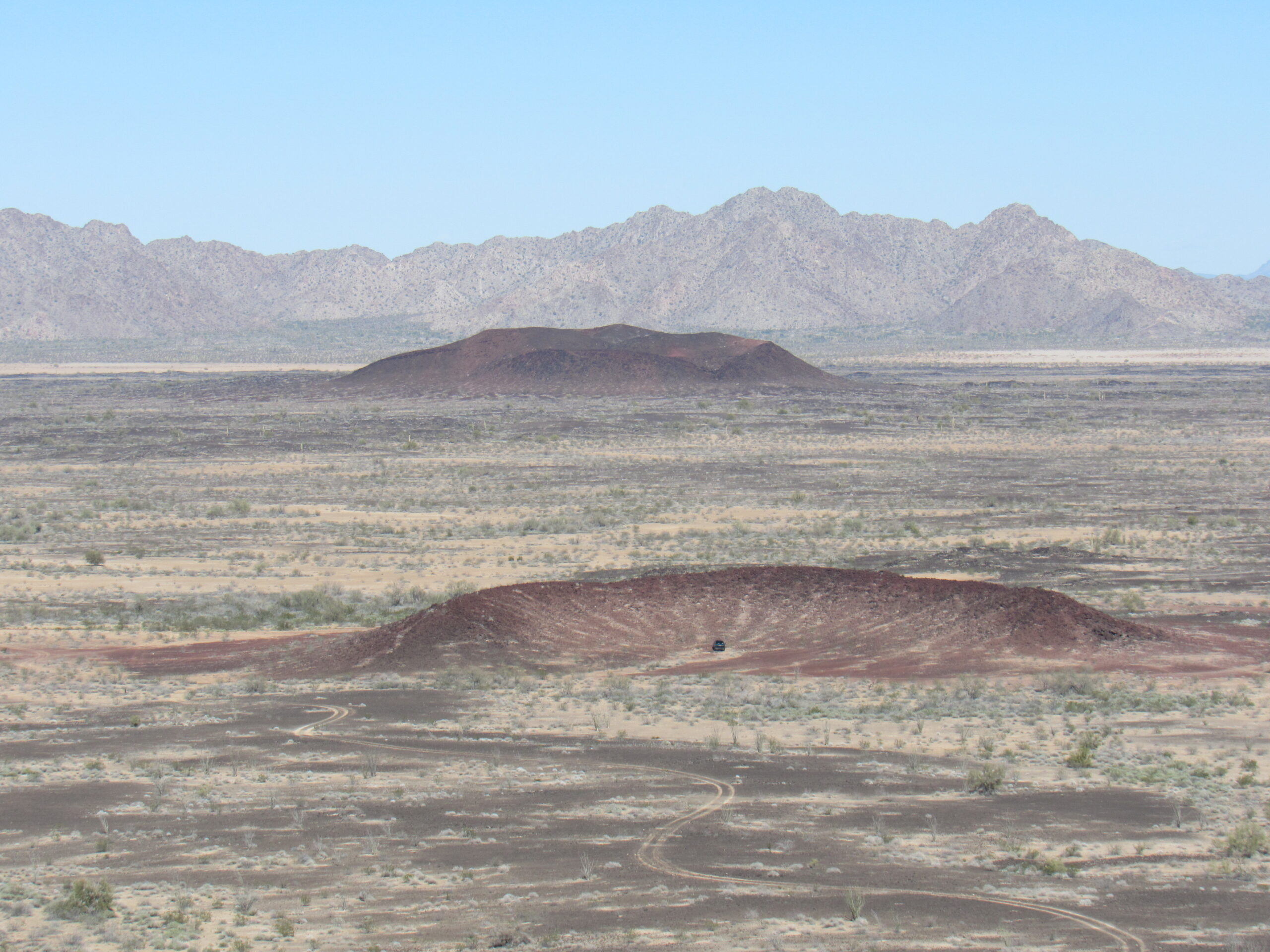

From the summit, we could see back to camp. This is a bit of a telephoto, clearly showing the truck inside our little crater remnant. A mile and a half beyond our camp is Point 962, and 4 miles beyond that sits the Sierra Pinta.

A little to the left of the above shot is this one, which shows Point 946 on the left and the smaller Point 830 on the right side.

Point 946 is the bigger one on the left; Point 830 is the little one on the right. Both of these are beyond the Camino. 946 is 1 KM beyond, and 830 is only 1,000 feet beyond.

Here’s one more crater, Point 911. All of these craters are within the lava field.

That’s Point 911 out there. It sits to the left of the previous picture, and is 2 miles beyond the road.

This next picture, I almost wish I didn’t have to show you, but for the sake of completeness, I guess I have to. See the dark line that stretches into the distance, to the southeast. That’s Trump’s border wall, a blight on the land. Here, you see it stretching off to the east.

In this next view, we are looking the other direction along the wall, to the southwest. I mean, we, like all Arizonans, knew that the wall was being built when Trump was in power, but to actually see it is a shock.

In the above photo, we are looking across the inside of Monument Bluff while I am standing on the high point of the crater rim. In the previous 2 pictures, everything on the other side of the wall is of course in Mexico. This next photo shows a different view into the crater – what’s that dark thing down there?

We went down to have a closer look, and found this.

No idea who built the cairn, or when. We walked downslope towards a natural opening in the south side of the crater wall. There was this bit of color along the way.

Once we exited the crater, we stood on its south side. We were only a thousand feet from the wall, but didn’t go over to it.

Even after billions spent to build the wall, those who wish to enter the US still do it. They cut holes in it; they climb up and over it; they set ladders up against it and climb to the top. If they want to enter, they will. Meanwhile, the natural passage of wildlife has been curtailed.

We found this shriveled boot on the ground, curled up from the heat.

This 50 MM shell casing lay on the ground, a relic of WWII days when aircraft such as the P51 Mustang would practice shooting in the remote desert. Markings on it show that it was made at the St. Louis munitions plant in 1945.

This was the view of our camp as we walked back across the flats.

The wind was blowing pretty steadily back in camp. I set up my tent and got ready for the night. The temperature dropped quickly and was down to 39 degrees just after sunset. Jake took this photo of camp from atop our little crater, about 50 feet up. I’m sitting in my lawn chair at the back of the truck, eating my soup from the tailgate.

Looking down to camp from 50 feet up. Monument Bluff sits out there. It is named for nearby Border Monument 181.

He took this photo looking north across the lava flow.

Once it was dark, he took more photos with a tripod and time exposure. Here’s the two of us at our campfire.

He also took pictures straight up at the night sky. No moon, no lights from any town, just really dark.

After I retired to my tent, I curled up in my sleeping bag and read from my Kindle for a while. Jake took this time exposure – that faint little Kindle really lit up the area.

Well, our first day on the Camino came to an end, with about 54 miles covered. It had been a great day, we had seen a lot, climbed a bit and basically had a really good time. Tomorrow we’d cover a lot more ground and see more of what makes this route so historic. So please stay tuned for Part 3.