Ghost town. What does the term even mean? A quick look on the internet took me to this site, where I learned that there was a lot more to it than I had thought. It turns out that there are over 130 of them in Arizona alone, and there are at least 5 different classifications of ghost towns, mostly based on how much of the original town is still left to see nowadays and what condition it’s in. Seriously, though, check out that site, it’s pretty cool.

In mid-January, Dottie and I decided to go visit one of them. We had heard of Ruby but neither of us had ever been there before. Getting there wasn’t a major commitment, as it was only 87 miles from our home in Tucson. Those miles were all paved, except for the last 6, which were on a pretty decent dirt road in the Coronado National Forest. We drove it in a Kia Soul, so it can’t be that bad. Two hours of driving saw us pulling up to the gate.

This sign greets you as you come up to the gate.

Ruby is situated at 4,500 feet elevation, so is a bit cooler than the low desert where Phoenix and even Tucson sit. It can still get pretty hot in the summer, though. It is open to visitors on Thursday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday, and you can arrange a permit on their website ahead of time to visit. The fee is a very reasonable 15 bucks.

As you enter the property, you can’t help but be impressed by the view of nearby Montana Peak, elevation 5,376 feet.

Once we drove in, we soon found the caretaker. Two other couples were already with her, and she gave us a brief history of the town. Leslie has a personal history as colorful and interesting as Ruby itself, and she struck us as the perfect person to be the caretaker of this place.

She gave us a map which explained the layout of the town, gave us a quick rundown of what was where, then set us loose to walk around the place at our own pace.

The raison d’être of Ruby was mining. The first mining claim was recorded in 1877, when early prospectors discovered gold and silver on or near the surface. In the early days, it was called Montana Camp, and up until 1912 it produced mostly gold and silver, with a population not above 50. When Arizona achieved statehood in 1912, the camp merited its own post office. The maiden name of the postmaster’s wife was Ruby, and that’s the name that stuck.

The first spot we visited was this one. “Hutch” lived here – he was a tall man with a handlebar moustache, and a master mechanic who kept the mill operational.

A short walk up a hill took us to what is left of the assay office. This is where samples of the ore were tested to evaluate their quality.

I loved this little building. The cartographer would be the person responsible for preparing maps of the mine, all of the underground shafts and tunnels.

We came upon this pile of adobe bricks.

If left out in the open and unprotected from the elements, adobe will eventually return to the stuff from which it is made, like these.

We liked the look of this hand-made stone wall.

This is the headframe. It would mark the top of the hoist, which carried miners down a vertical shaft 750 feet deep. That’s the height of a 75-storey building! They would work an 8-hour shift, then come back up again to the land of the living. At one point, there were 325 employees working 3 shifts, 7 days a week. Every day, they would haul 15 tons of ore by truck the 35 miles to Amado, where it would then go by rail to the smelter at El Paso, Texas. By the time the mine closed, 772,000 tons of ore worth seven million dollars had been processed. What had begun as a gold and silver operation eventually deepened to the 750-foot lead mine.

This had been a warehouse where equipment was stored.

This is Town Lake, one of two on the property.

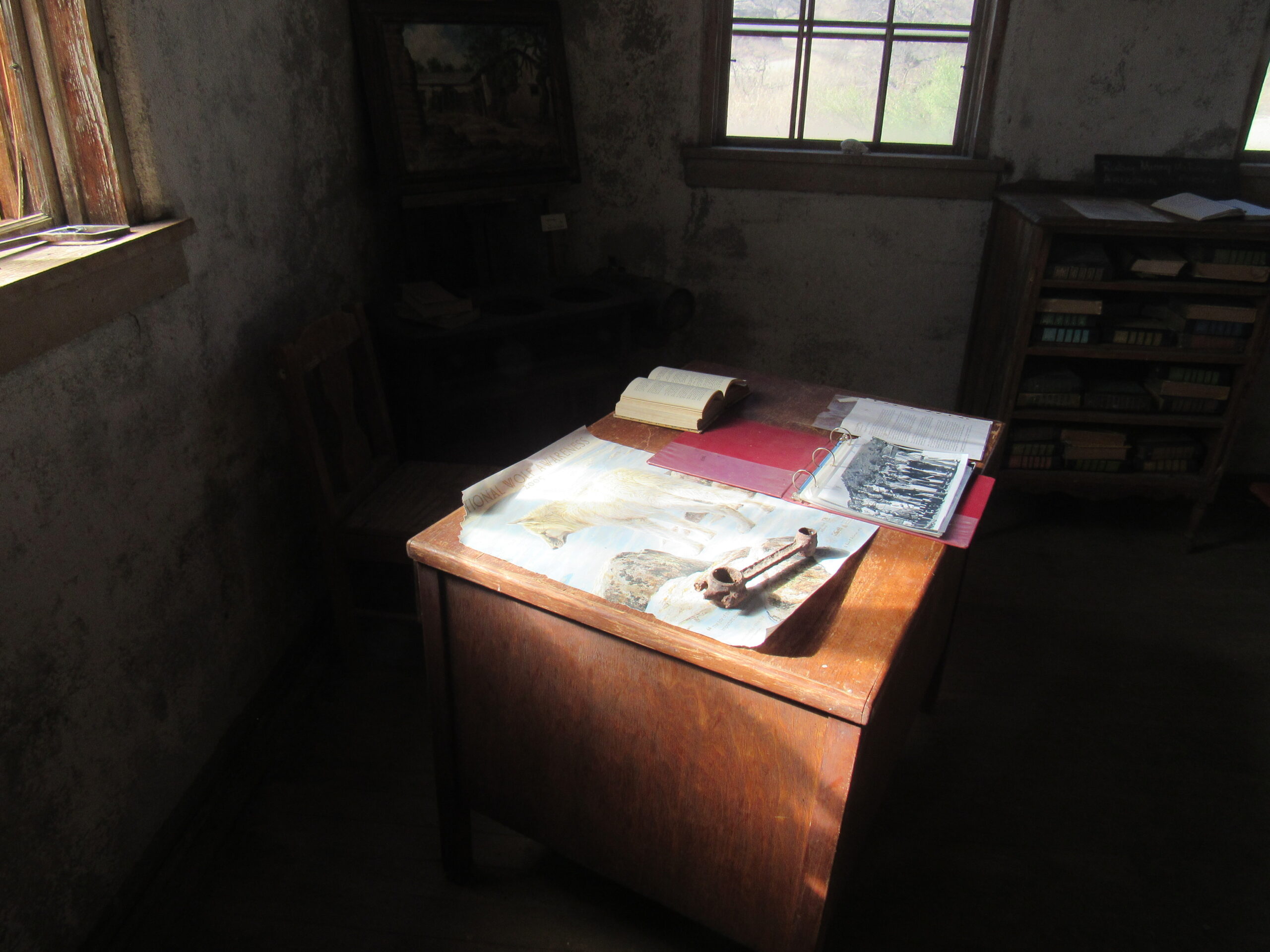

Here is the building that served as the office safe, where they kept records, cash, checks and anything else really important.

This was the path that led up to the Duff House. The mine superintendent Grover Duff lived here with his wife Lundy and their daughter Kathleen, who was born in Ruby. Lundy worked as an anesthesiologist at the town hospital.

This is the entrance to their house.

And here are shots of the inside.

That house may not look like much, but it was palatial when compared to the bunkhouses where some of the single men lived, and the tent camp where many others lived.

This next picture is all that’s left of the 9-bed hospital. Dr. Julius Woodard was the town doctor. His office was here. His wife Pauline was the nurse, and later on so was Ann Worth when her husband Norman “Red” Worth, a diesel mechanic, moved to Ruby. Julius arrived in 1930 and apparently was a well-respected, loved, knowledgeable and compassionate physician who performed surgery, cared for the sick, delivered babies, set broken bones and made house calls. He even organized a scout troop. He moved to Tucson in 1940 and a heart attack took his life at the young age of 54.

Next to the hospital were a couple of bunkhouses where some of the single men lived and took their meals. There’s not much left of them now.

In another part of the town can be found this building, the Cargill residence. Daniel and Constance lived there with their yellow tabby cat named Ghandi. He was the accountant for the Eagle-Picher mining company and he also managed the Mercantile for a brief time.

Farther up the hill was the Morton House. Eric Morton, the general manager of the mine, and his wife Annie, lived here. He also ran the pool hall and hosted frequent bridge parties.

The Morton place is high up on a hill that the miners called “Snob Hill”. The caretaker Leslie calls it “Two-Bar Hill”, as it is the only place she can go to get cell-phone reception. This house is in pretty good shape, and is used as a place to house and teach students who periodically come to Ruby to study the flora and fauna of the area. Here are some shots taken inside the house.

Out behind the building are a couple of cisterns to capture rain-water.

Nearby was this strange enclosure.

And this old boat.

The house where the caretaker lives was once used by the Justice of the Peace for Santa Cruz County to hold court sessions. There’s another cistern there. Water was a precious commodity at Ruby.

This house served to house visiting officials of the mining company, as well as serving as a place to hold court sessions.

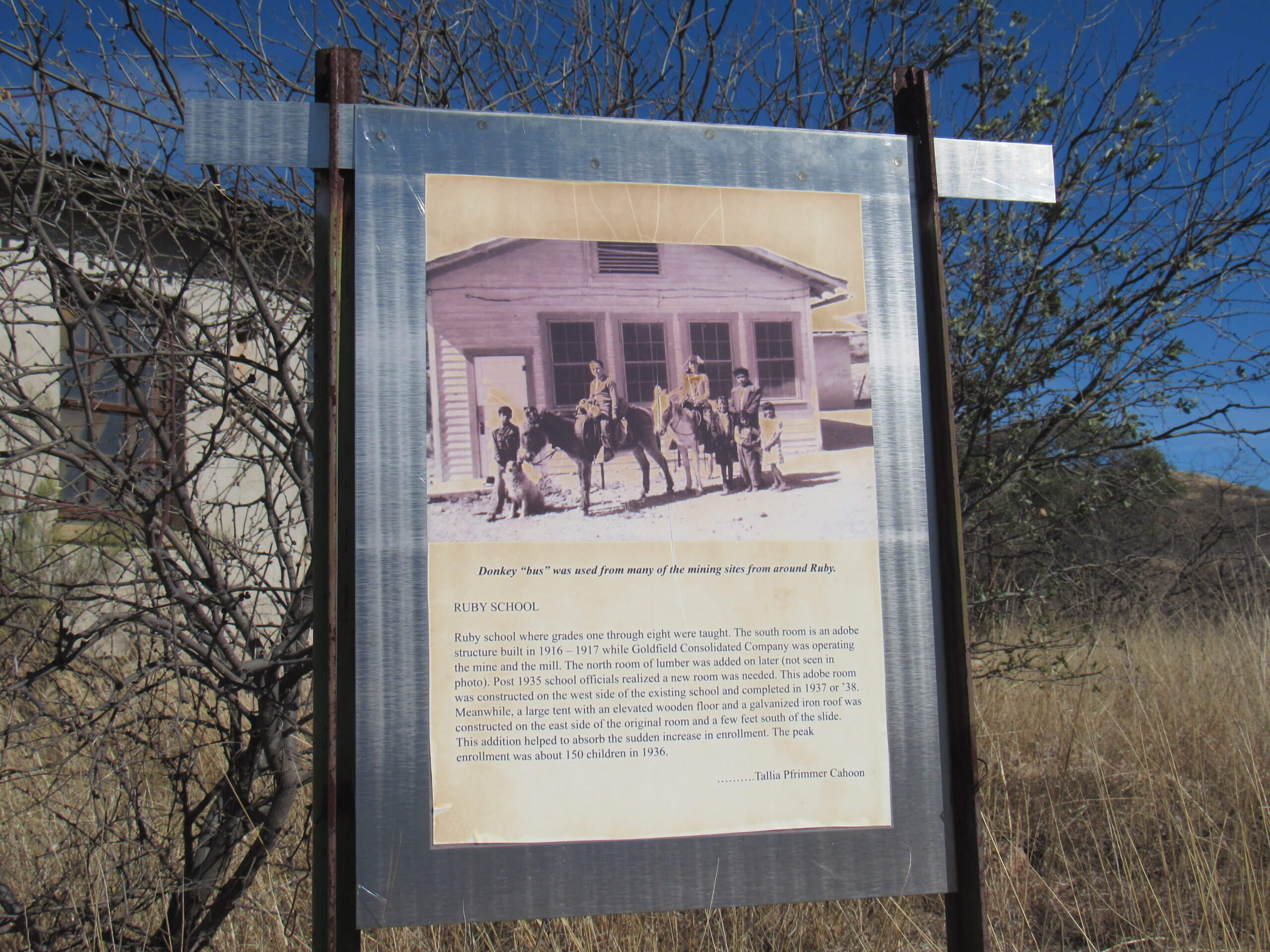

This sign is in front of the old schoolhouse. At its peak there were 150 students here in 1936.

In its heyday, there were as many as 150 students attending school here in Ruby, in 1936. Grades one through eight were taught, and there were 4 teachers.

Most of the building is still standing today.

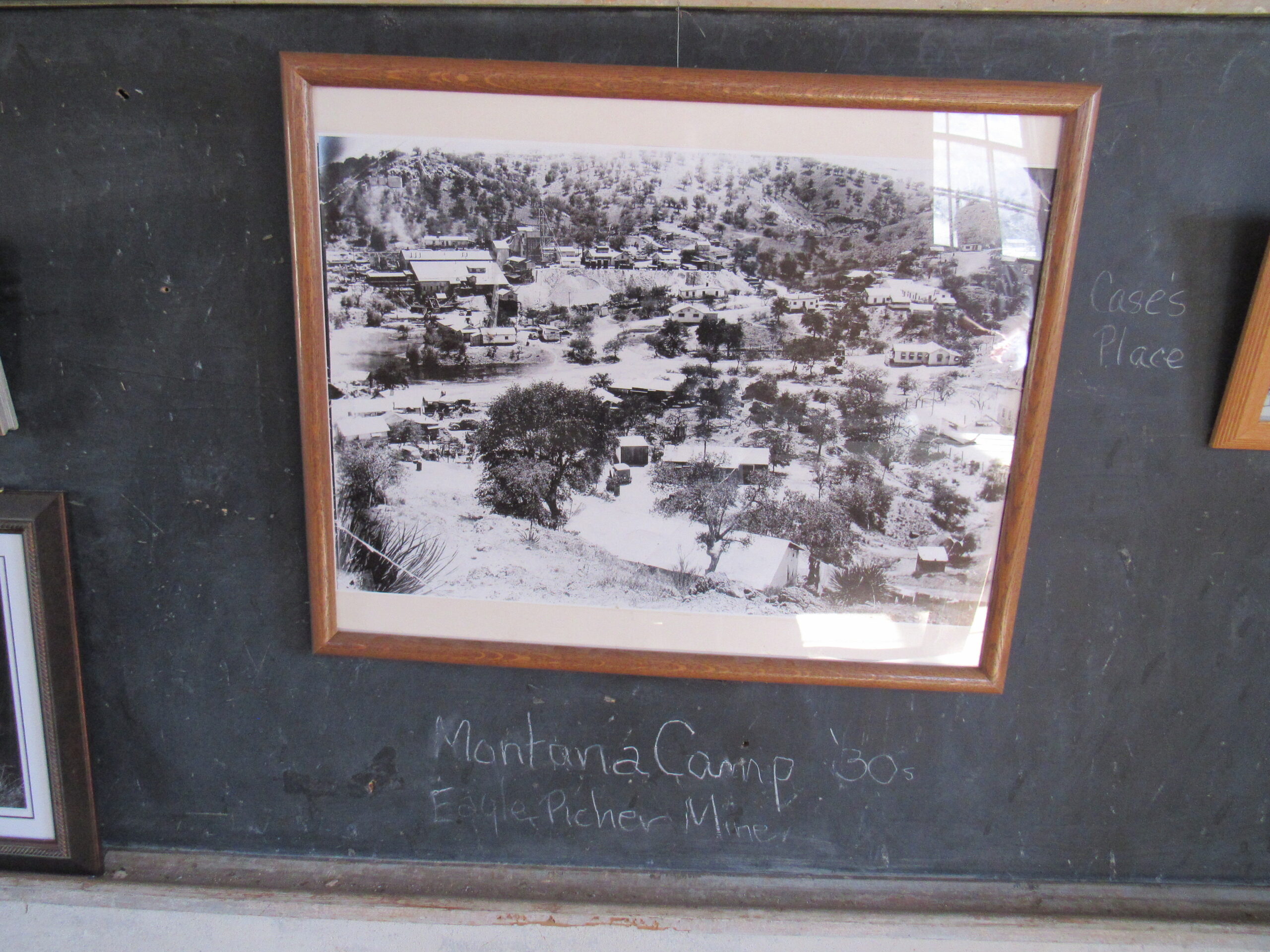

Inside the old schoolhouse, one of the rooms is now used as a museum. Here are some of the things to be found there. The first photo shows an overview of Ruby in its heyday. There were 1,200 people living here at its busiest.

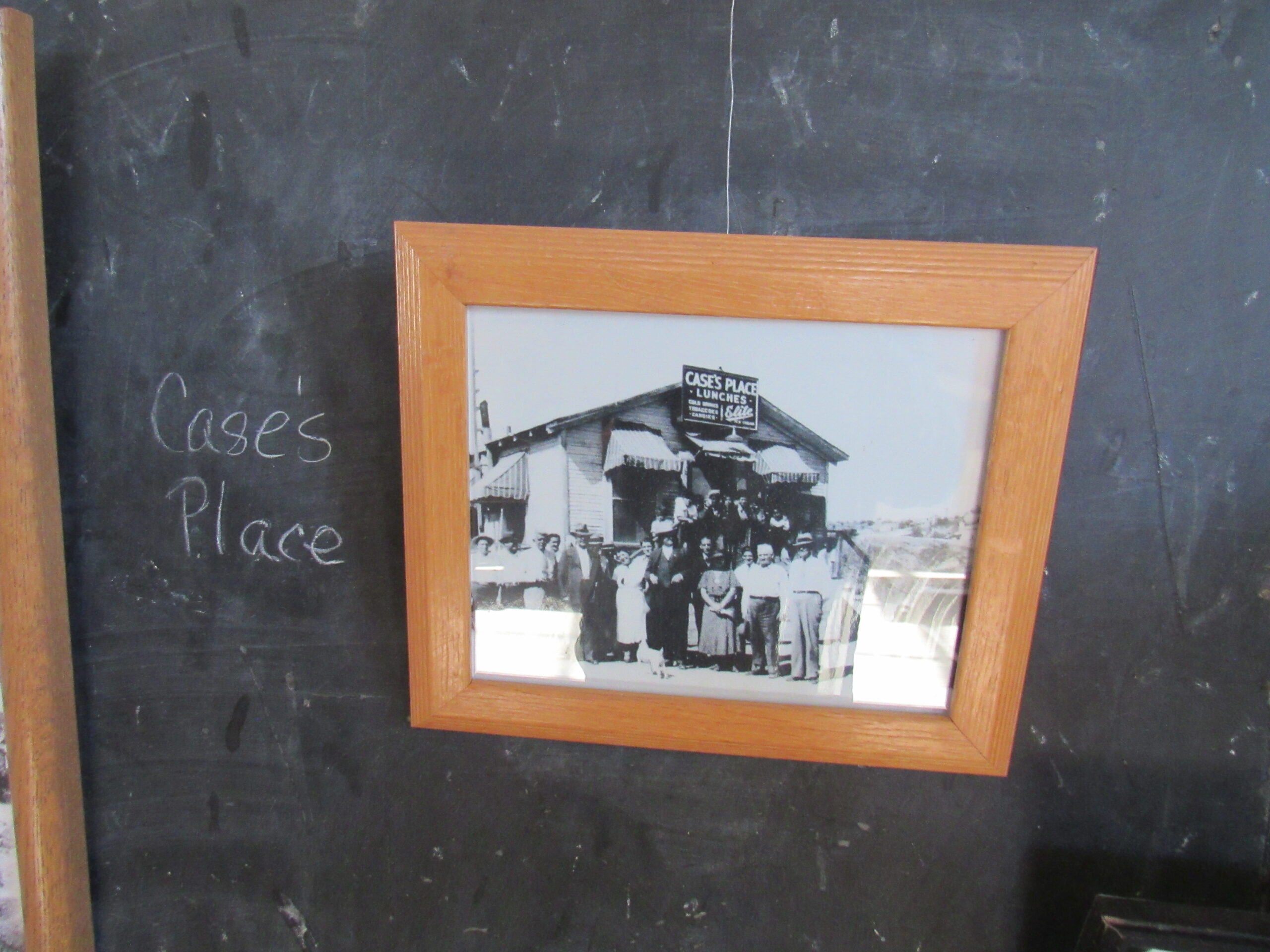

This photo shows Case’s Place. Charlie Case helped build the pipeline, did carpentry work and served as the Justice of the Peace. They served sandwiches, homemade pies, cakes, malts, milkshakes, tea, coffee and sodas, including Delaware Punch. Ice cream cones were a nickel. The Cases lived in an attached apartment.

Here are photos of some of the miners who worked at Ruby.

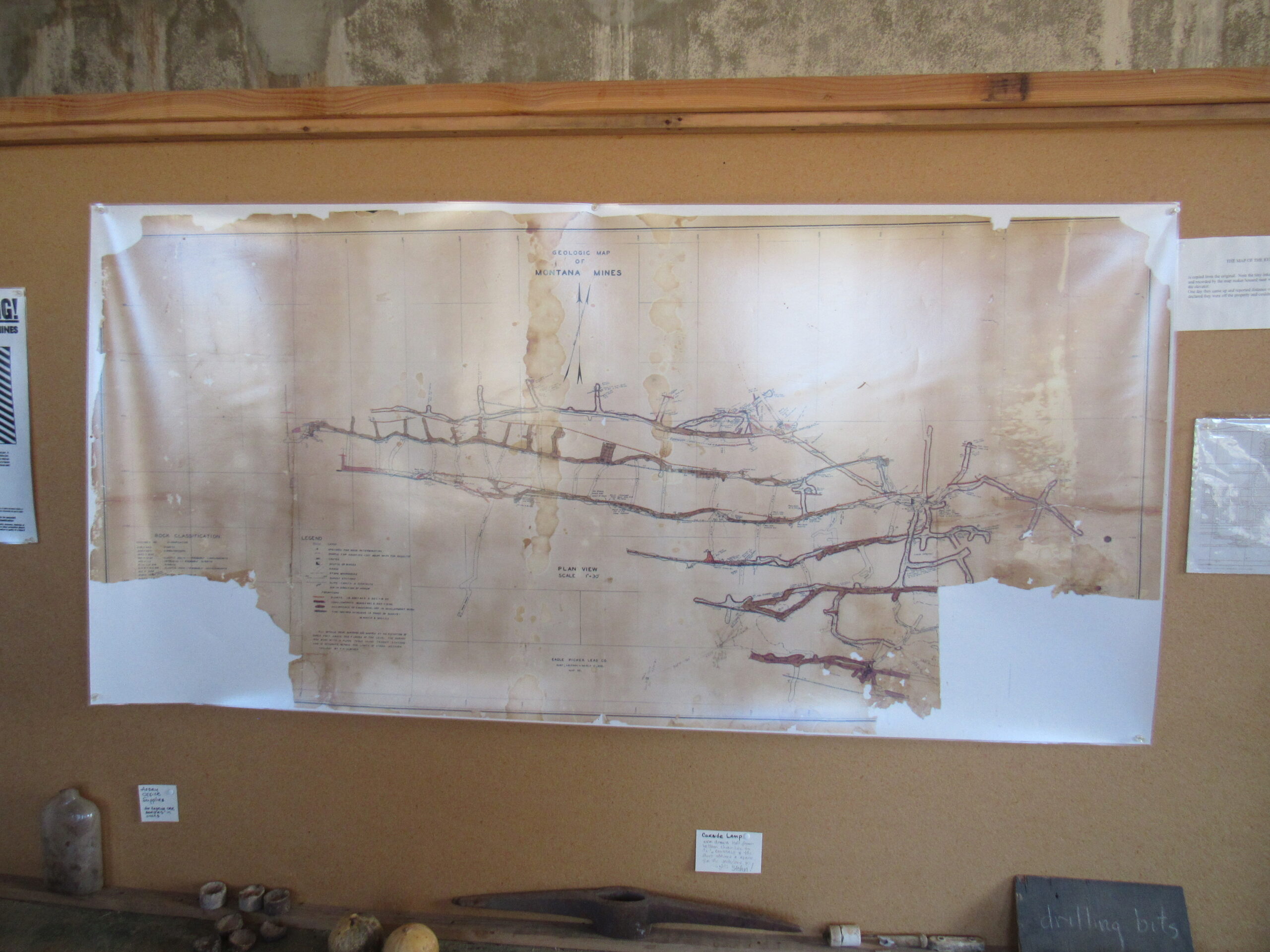

Here is a map showing the underground workings of the mine.

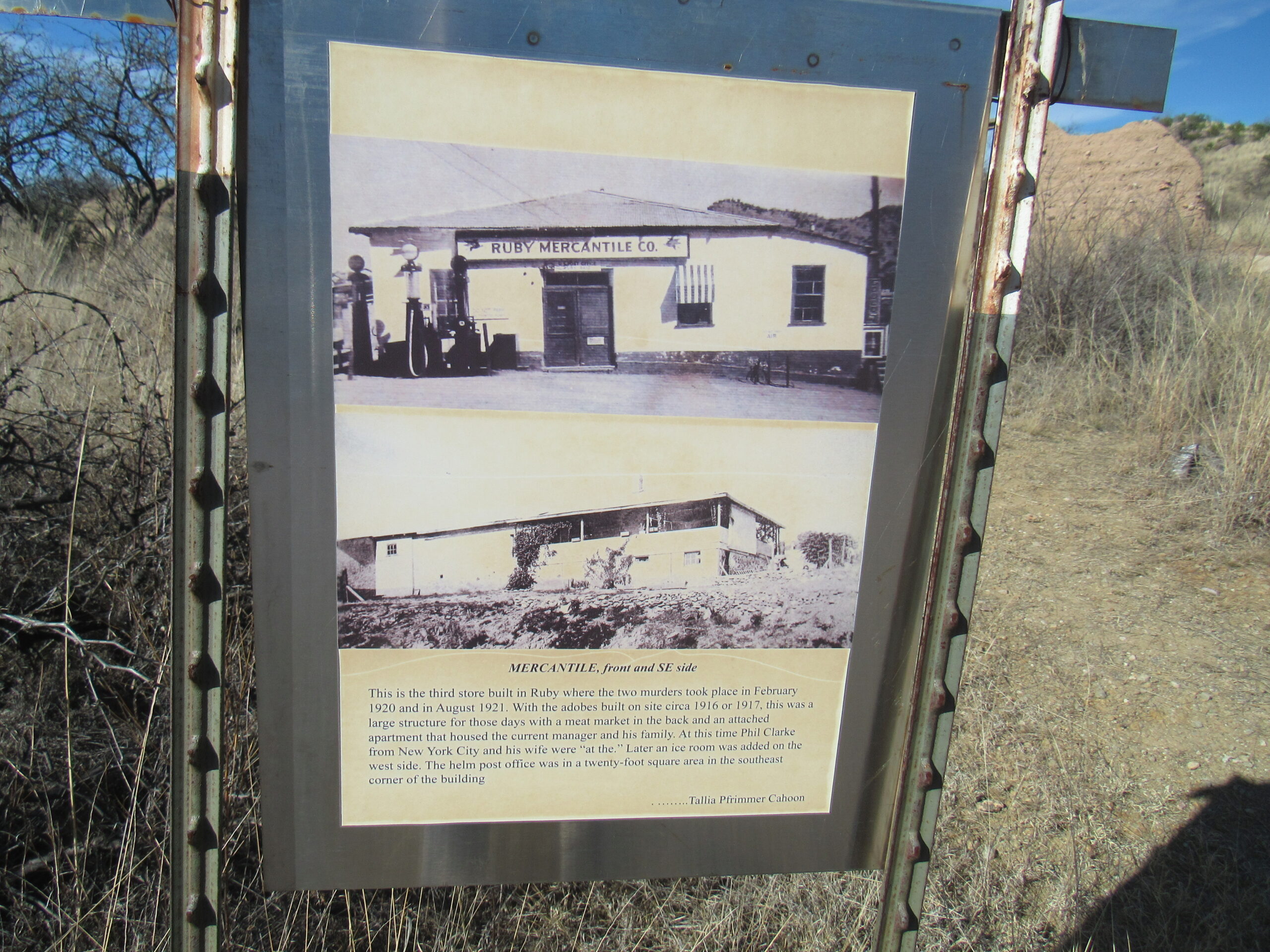

This sign tells us about the Ruby Mercantile. In the early 1920s, there were 2 double murders that occurred at the Merc.

Nowadays, this is all that remains of the Mercantile.

The only toilet at Ruby, used by one and all.

In 1936, the town spent six hundred dollars to build this jail. Before that, they chained drunks to the mesquite trees.

One of my favorite sights at Ruby was this old truck.

Many times over the years, I have come across old vehicles in the desert. My go-to source of information on these is my brother-in-law Lee Harrison, and there aren’t many he can’t identify. He responded right away to my request on this one, telling me it is a 1941 Ford. Here is what one of them looks like when new.

In one corner of the town is a deep open shaft. Bats emerge at dusk during the early summer and fly around during the night, eating insects. Scientists have said that there is a nursery colony of half a million Mexican Freetail bats, but the actual number varies with storms and other factors. We weren’t there at the right time of the year to see them, but have seen this evening exodus in other places in the summer here in the Sonoran Desert.

Ruby is only 4 miles from the Mexican border, but caretaker Leslie said that she hasn’t had any problem with indocumentados at Ruby. The townsite is such a quiet place, and even on the days when a few visitors arrive, all you might hear are a few distant voices, some birds chirping, and the wind blowing. It’s hard to imagine that at one time, there were 1,200 people living there – three shifts in the mine, children attending school, families going about their daily lives. Most of the original buildings have vanished. There was a tent city where a lot of the men lived, but there’s no trace of that now. There was a baseball team and a rifle team back in the day. The mine was finally closed in 1940 when the ore gave out. The Eagle-Picher company sealed the mine by dynamiting the main shaft entrances. There was a total of 19 patented mining claims covering 362 acres.

The town sat, pretty-much ignored, until 1961, when 5 Tucsonans bought Ruby as a real-estate investment. They thought of keeping it as a private retreat, or to maybe develop it into a movie set and a private club. The idea was even floated of developing a TV series around Ruby and its history, but none of these came to pass. Security became an issue when 2 men who had snuck in drowned in the lake.

There was thought of reclaiming the tailings to extract the gold and silver left in them. Several short-term mining leases were granted up until 1990, but there were no results promising enough to warrant continuing.

In the late 1960s, hippies moved in and squatted there until 1976 when the Forest Service had them legally removed. In 1975, Ruby was entered into the National Register of Historic Places as a historic property. A film was made there, a 1-hour documentary called “The Ghosts of Ruby”, which aired on the PBS show Nature on May 9, 1993. In 1998, Arizona Game and Fish spent $30,000.00 to fence the town against trespassing cattle. Since that was done, water quality in the lakes has improved, and native vegetation has come back.

There has been a series of caretakers over the years. The job would require a special type of person, someone who can appreciate living off the grid without many of the creature comforts the rest of us take for granted. The current caretaker, Leslie, seems well-suited for the job.

Several reunions have occurred at Ruby, well-attended by 100 to 200 people each time, people who once lived there. They were held in 1993, 1996, 2000, 2001 and 2002, but I don’t know if any were held since then. The thing about reunions is that you eventually run out of people to attend, assuming they are for those who were once part of what you are celebrating. My high-school reunions are a perfect example. We had our 55th reunion in 2019, but I know for a fact that our 60th, to be held in 2024, will sadly be without several who attended the previous ones.

In closing, if you ever get a chance to visit the old mining town of Ruby, go do it. Pack a lunch and bring a camera – you’ll have a great time.